Introduction

Worldwide, there are more than 20 million inguinal hernia repairs performed annually. About 800,000 of these are performed in the United States. These statistics make inguinal hernias one of the most common medical conditions encountered by a general surgeon. The ureter is a retroperitoneal organ, and ureteral involvement with an inguinal hernia is rare. Only about 140 cases of ureteral inguinal hernia were reported through 2009.[1] Involvement of the ureter may be undetected preoperatively, and the general surgeon needs to be keenly aware of a ureteral inguinal hernia because intra-operative iatrogenic damage to the ureter can have serious consequences.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

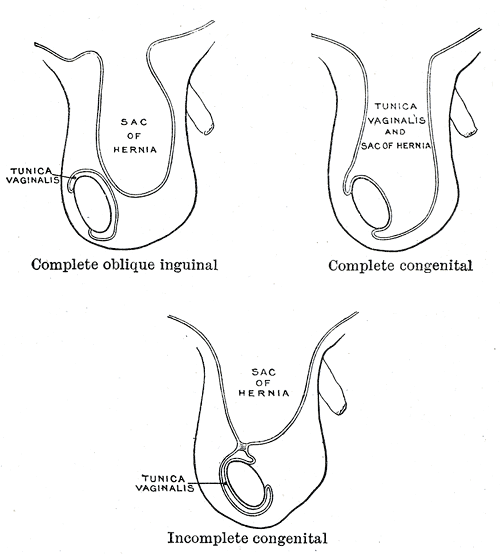

Inguinal hernias can be classified as congenital or acquired. The congenital type is related to a patent processus vaginalis, an invagination of the parietal peritoneum, which precedes testicular descent through the inguinal canal during embryogenesis. These are indirect inguinal hernias which protrude through the internal inguinal ring lateral to the epigastric vessels. They are about twice as common as direct inguinal hernias. There is a recent debate that all indirect inguinal hernias result from a processus vaginalis that had never closed. Work by Jiang and Mouravas suggests that adult indirect inguinal hernias may develop after the long-term buildup of pressure on a processus vaginalis that had closed along its entire length except at the neck of the hernia sac.[2][3] The acquired type of an inguinal hernia is related to a weakening or disruption of the abdominal wall tissues due to several contributing factors, including older age, smoking, increased intraabdominal pressure such as due to a chronic cough or pregnancy, and connective tissue abnormalities. Acquired inguinal hernias are typically direct inguinal hernias where intraabdominal contents protrude through Hesselbach’s triangle, medial to the inferior epigastric vessels.

Epidemiology

First described in 1880, most reported cases of ureteral involvement with a groin hernia have been ureteral inguinal hernias. Ureterofemoral and ureterosciatic hernias are also seen. Both genders are affected, although ureteral inguinal hernias are more common in men. Risk factors for developing a ureteral inguinal hernia include male gender, increased age, and a history of a kidney transplant. Ureterofemoral hernias are more commonly seen in women.[4] Bladder involvement with an inguinal hernia is also possible; this is typically associated with a direct inguinal hernia and presents with bladder outlet obstruction symptoms such as urinary retention, frequency, and hematuria.[5]

Pathophysiology

There are 2 types of ureteroinguinal hernias: paraperitoneal and extraperitoneal.[6] Both types are usually indirect hernias, exiting the abdominal cavity through the inguinal canal and protruding laterally to the inferior epigastric vessels. The paraperitoneal type is more common (80%) than the extraperitoneal type. As the ureter is a retroperitoneal structure, it is involved as part of the hernia sac wall, not as an internal component of the hernia sac.

The paraperitoneal type of ureteroinguinal hernia is a sliding hernia. Paraperitoneal ureteral inguinal hernias may develop due to traction on the ureter by abnormally adherent posterior parietal peritoneum.

Extraperitoneal ureteral inguinal hernias do not involve the hernia sac. These hernias result from an embryologic anomaly in which the ureteric bud separates from the Wolffian duct late as it descends to form the epididymis and testis.[7] In the extraperitoneal ureteroinguinal hernia, the ureter herniates without the peritoneum attached. The extraperitoneal type may be associated with congenital kidney malformations.

History and Physical

Though specific symptoms are possible, most patients with a ureteral inguinal hernia present no differently than the typical groin hernia. In either type of ureteral inguinal hernia, obstructive uropathy and urological symptoms may be present, regardless of the length of ureter involved. Flank pain, dysuria, hematuria, acute urinary obstruction, double-phase micturition requiring pressure to initiate or terminate voiding associated with an inguinal hernia may signal the presence of a ureteral inguinal hernia. On laboratory investigation, the clinicians may see an acute kidney injury.[8]

Evaluation

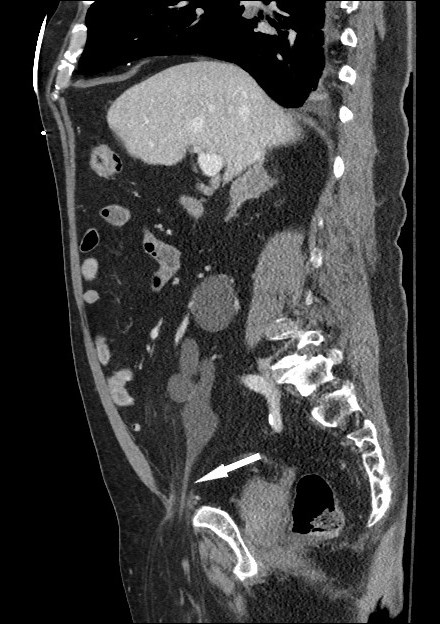

Specific imaging studies are not routinely obtained in the preoperative workup of an inguinal hernia. However, if concerning signs of symptoms as stated above are noted, these findings should prompt preoperative imaging. An ultrasound may demonstrate hydronephrosis of the ipsilateral kidney. Intravenous pyelography may demonstrate the telltale “curlicue” sign, with the ureter seen in a pathognomonic spiral or loop-the-loop formation. In patients with unexpected abnormal renal function, Gellett describes the potential for preoperative diagnosis by computed tomography (CT) with confirmation of a ureteral inguinal hernia on delayed, post-contrast, 3-dimensional reconstruction.[9] CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may show the ureter entering the inguinal canal or extending beyond the bony pelvis. Nephroptosis visible on cross-sectional imaging may accompany ureteral inguinal hernia. This phenomenon is likely due to the loss of the perirenal supportive tissue into the hernia sac, rather than traction of the ureter on the kidney.

Treatment / Management

A ureteral-inguinal hernia repair should be performed in an open manner, not laparoscopically, if diagnosed preoperatively.[5] Repair of ureteral inguinal hernias may involve a simple reduction of the ureter with the hernia sac. Depending on the length of ureter involved, repair may require resection of the redundant ureter with primary anastomosis, ureteroneocystostomy, psoas hitch, Boari flap, or transureteroureterostomy.[8] The surgeon should resect the necrotic or dilated areas of the ureter. In the case of a complicated repair, postoperative CT imaging should be done to ensure the patency and proper placement of the ureter back in the retroperitoneal space. Ureteral protection with a ureteral stent improves the identification of an involved ureter when it is known preoperatively.[5] In a patient unable to withstand an operation, palliation of obstructive uropathy may also be achieved by placement of a nephrostomy tube or a nephro-ureteral stent.[10](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

Involvement of the bladder with an inguinal hernia is estimated to occur in 1% to 4% of all inguinal hernias and is more common than involvement of the ureter. Urologic organ involvement should be considered in any patient presenting with urologic symptoms in conjunction with an inguinal hernia.[4]

The differential diagnosis includes the following:

- Inguinal hernia with bowel, omentum, or extraperitoneal fat

- Femoral hernia

- Hydrocele or varicocele

- Urologic malignancy

- Malignancy of the pelvic organs or retroperitoneal space

Prognosis

Most patients undergoing any form of inguinal hernia repair generally have a good prognosis, as hernia repair surgery is both safe and effective. Following open surgery, the patient can usually resume their normal activities within a week or two. After any hernia surgery, the patient should avoid heavy lifting for six to eight weeks to permit full healing of all muscles and other tissues.[11]

Complications

Complications of an inguinal hernia include possible incarceration or strangulation of the hernia. Strangulation is a life-threatening emergency. If not repaired, hernias tend to enlarge over time.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Following surgery, patients should receive counsel to maintain healthy body weight and avoid activities that involve heavy lifting or even straining during bowel movements. Following these instructions can prevent the recurrence of the hernia.

Pearls and Other Issues

Ureteroinguinal hernias may cause hydronephrosis or kidney injury, or they may be clinically silent. Clues to the involvement of the ureter with an inguinal hernia include unexplained hydronephrosis, renal failure, or urinary tract infection, especially in a male. When suspected, the involvement of the ureter should be investigated preoperatively and diagnosed via CT or intravenous pyelography. Ureteral involvement with an inguinal hernia is rare; however, the general surgeon should keep this event in mind to avoid iatrogenic urologic damage.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

With the commonality of cross-sectional imaging of the abdomen and pelvis performed for a variety of reasons, radiologists should note incidental ureteral involvement with an inguinal hernia. The surgeon should also look out for these findings. Adjunctive studies are not routinely performed during the work-up of an inguinal hernia, although they are beneficial in the case of a ureteral inguinal hernia. Surgeons should be acutely aware and knowledgeable of a ureteral inguinal hernia to avoid potential urologic damage.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Sharma RK, Murari K, Kumar V, Jain VK. Inguinoscrotal extraperitoneal herniation of a ureter. Canadian journal of surgery. Journal canadien de chirurgie. 2009 Apr:52(2):E29-30 [PubMed PMID: 19399195]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJiang ZP, Yang B, Wen LQ, Zhang YC, Lai DM, Li YR, Chen S. The etiology of indirect inguinal hernia in adults: congenital or acquired? Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2015 Oct:19(5):697-701. doi: 10.1007/s10029-014-1326-5. Epub 2014 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 25431254]

Mouravas V, Sfoungaris D. The etiology of indirect inguinal hernia in adults: congenital, acquired or both? Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2015 Dec:19(6):1037-8. doi: 10.1007/s10029-015-1365-6. Epub 2015 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 25731950]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEilber KS, Freedland SJ, Rajfer J. Obstructive uropathy secondary to ureteroinguinal herniation. Reviews in urology. 2001 Fall:3(4):207-8 [PubMed PMID: 16985719]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYahya Z, Al-Habbal Y, Hassen S. Ureteral inguinal hernia: an uncommon trap for general surgeons. BMJ case reports. 2017 Mar 8:2017():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-219288. Epub 2017 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 28275027]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePollack HM, Popky GL, Blumberg ML. Hernias of the ureter.--An anatomic-roentgenographic study. Radiology. 1975 Nov:117(2):275-81 [PubMed PMID: 1178852]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLu A, Burstein J. Paraperitoneal inguinal hernia of ureter. Journal of radiology case reports. 2012 Aug:6(8):22-6. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v6i8.1027. Epub 2012 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 23365714]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcKay JP, Organ M, Bagnell S, Gallant C, French C. Inguinoscrotal hernias involving urologic organs: A case series. Canadian Urological Association journal = Journal de l'Association des urologues du Canada. 2014 May:8(5-6):E429-32. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.225. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25024798]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGellett LR, Roobottom CA, Wells IP. Inguinal hernia--an unusual cause of bilateral renal obstruction. Clinical radiology. 2000 Dec:55(12):984-5 [PubMed PMID: 11124085]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHe L, Herts BR, Wang W. Paraperitoneal ureteroinguinal hernia. The Journal of urology. 2013 Nov:190(5):1903-4. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.08.005. Epub 2013 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 23933463]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShao JM, Elhage SA, Prasad T, Colavita PD, Augenstein VA, Heniford BT. Outcomes of Laparoscopic-Assisted, Open Umbilical Hernia Repair. The American surgeon. 2020 Aug:86(8):1001-1004. doi: 10.1177/0003134820942162. Epub 2020 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 32853047]