Introduction

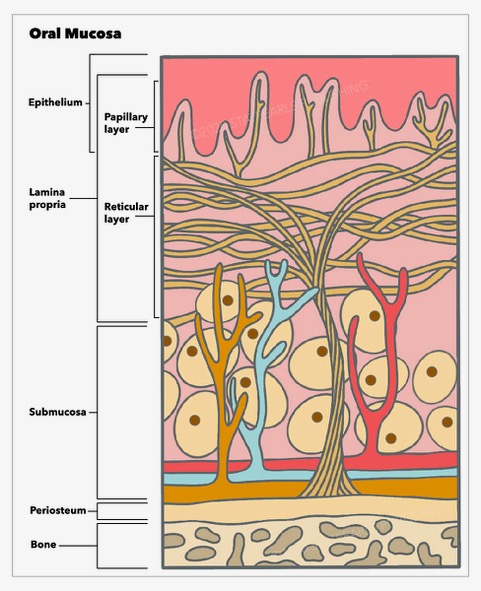

Cancer of the oral mucosa originates from the mucosa lining of various structures within the oral cavity, including the lips, cheeks, teeth, gums, anterior two-thirds of the tongue, the floor of the mouth, the hard palate, and the retromolar trigone posterior to the wisdom teeth. The oral cavity shares a close anatomical relationship with the oropharynx, delineated by key boundaries such as the lower edge of the soft palate, the division between the anterior two-thirds and posterior one-third of the tongue, and the anterior pillars of the tonsils. This helps distinguish oral cavity structures, particularly the soft palate, from oropharyngeal structures, such as the faucial and lingual tonsils (the tongue base), aiding in accurate diagnosis and treatment planning (see Image. Layers of Oral Mucosa).[1]

Primary risk factors for oral mucosal cancer include smoking and alcohol consumption, particularly when combined, while additional risks stem from human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and stem cell transplants.[2] Oral mucosal cancer treatment typically revolves around surgery as the mainstay, often with adjuvant radiotherapy for advanced-stage cancers.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Understanding the multifaceted etiology of oral cancer is paramount for effective prevention and early detection. Various risk factors, including tobacco and alcohol use, HPV infection, and stem cell transplants, contribute to the development of oral malignancies, highlighting the importance of comprehensive awareness and intervention strategies.

Tobacco

Smoking tobacco is the greatest risk factor for developing oral cancer due to carcinogenic chemicals, including nitrosamines, benzopyrenes, and aromatic amines.[3] The risk of developing oral cancer is 3 times higher in smokers compared with non-smokers. Individuals are also at risk from secondary passive smoking environments, particularly with chronic second-hand exposure.[4] The results of studies demonstrate a synergistic relationship with alcohol consumption, resulting in a higher risk of malignancy.[5]

In various parts of the world, tobacco is consumed through chewing or holding it in the mouth instead of smoking. Nicotine is absorbed through the mucous membranes, producing the desired effect. This substance is closely linked to oral cavity cancers due to direct contact with affected tissues and is also associated with oropharyngeal malignancies.

Chewing betel quid, also known as "pan" or "paan," involves a mixture of betel leaf, areca nut, slaked lime, and tobacco, which is then chewed. This widespread practice in South Asia and parts of Micronesia is linked to a higher risk of malignancy compared to smoking tobacco alone due to prolonged exposure of carcinogens to cells in the mouth.[6] Snuff/snus is a moist form of smokeless tobacco often placed under the upper lip for extended periods. This habit is prevalent in Scandinavia and North America.[7]

Alcohol

Alcohol consumption, especially when combined with smoking, elevates the risk of oral cancer. Although ethanol is not a carcinogenic substance, it enhances the permeability of the oral mucosa, making it more susceptible to damage from other carcinogens.[8]

Human Papillomavirus

HPVs, mainly types 16 and 18, are associated with malignancies, notably cervical cancer and oropharyngeal cancer, especially tonsillar and base of tongue tumors. Although the association with oral cancers is not as well-established, some evidence supports such a connection. In the oral cavity, HPV infection is 4 times more likely in individuals with squamous cell carcinomas compared to those with healthy mucous membranes.[9] The primary mode of infection transmission is through oral sexual contact.

Stem Cell Transplants

Individuals who have undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplants face a significantly increased risk of developing oral cancer, ranging from 4 to 7 times higher than that of the general population. The development of graft-versus-host disease in the oral cavity often precedes the onset of cancer. Common symptoms include mucositis, xerostomia, and lichenoid changes. Notably, oral cancers most frequently arise in the tongue and salivary glands approximately 5 to 9 years after transplant.[10] Moreover, due to the immunosuppressive nature of the regimen, solid organ transplant recipients also experience heightened susceptibility to oral cavity malignancies.[11]

Epidemiology

Distinguishing between the incidence and prevalence of oral cavity cancers poses challenges due to variability in categorization. Despite being 2 distinct diseases, many older national databases still aggregate data on them. According to the American Cancer Society's Global Cancer Facts and Figures 4th edition report in 2018, the global incidence represents approximately 2% of all cancers. In males residing in countries with a medium Human Development Index, lip and oral cavity cancer, along with lung cancer, rank among the most frequently diagnosed cancers.

Although the incidence of oropharyngeal cancer, especially HPV-positive cancers, is on the rise, there is a declining trend in the incidence of oral cavity cancers. Countries in South Asia, such as India, Sri Lanka, and the Pacific Islands, report the highest incidence of oral cavity and lip cancers globally.[12] The incidence is approximately twice as high in males compared to females, likely due to a higher prevalence of carcinogenic activities such as smoking and alcohol consumption.

Histopathology

Squamous cell carcinomas account for more than 90% of oral cavity cancers.[13] Premalignant lesions exhibiting dysplasia, such as erythroplakia and leukoplakia, are associated with the development of squamous cell carcinomas.

Other malignant types of tumors in the oral cavity include verrucous carcinoma, mucosal melanoma, Kaposi sarcoma, primary intraosseous squamous cell carcinoma, osteosarcoma, and rare malignant tumors such as fibrosarcoma, liposarcoma, lymphoma, chondrosarcoma, and plasmasarcoma.

History and Physical

Oral mucosal cancer presents with varied clinical manifestations depending on its location. In its early stages, it may manifest as irregular white, red, or mixed patches on the mucosa. As the cancer progresses, more advanced cases often exhibit an indurated raised nodule with an ulcerated surface. Location-specific symptoms may include dysarthria or difficulty protruding the tongue fully if the cancer affects the tongue area, causing tethering or pain. Cancer situated in the alveolar ridge may lead to loose adjacent teeth. Furthermore, as the cancer spreads locally or systemically, patients may experience dysphagia, odynophagia, hoarse voice, otalgia, weight loss, and lymphadenopathy.

A comprehensive clinical examination of the oral cavity plays a crucial role in identifying potential tumors and detecting concurrent tumors and/or spread. This examination involves using 2 tongue depressors and a reliable light source, along with a neck examination to assess for any lymphadenopathy. The regional neck lymphadenopathy is documented according to the anatomical levels I to VI. A flexible nasendoscopy is also recommended to evaluate for concurrent oropharyngeal or laryngeal tumors.

Evaluation

A comprehensive evaluation process, including clinical examinations, biopsies, endoscopic procedures, and imaging studies, is crucial for accurately diagnosing and staging oral mucosal cancer.

Biopsy

A biopsy is a crucial step in the initial investigation of oral lesions. Many lesions can be biopsied in an outpatient clinic if they are well-tolerated and easily accessible. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration may be performed for associated lymphadenopathy. However, for lesions located at the tongue base or more posterior regions, an examination under general anesthesia is necessary to obtain a tissue sample for histological analysis.[13]

Endoscopy

Although simple nasendoscopy in the clinic provides valuable insights, panendoscopy conducted under general anesthesia is essential to thoroughly examine for concurrent tumors in the pharynx and larynx. This procedure allows for comprehensive palpation and examination of the area, aiding in assessing tumor mobility and identifying any deep spread or fixation to underlying structures.

Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) scans with intravenous (IV) contrast are essential for thorough assessment. They evaluate the local extent of the tumor and its involvement in the bone or adjacent structures, lymph nodes, and chest. If the patient cannot tolerate iodinated contrast, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be utilized. Positron emission tomography (PET) scans may also be warranted to assess cases with unclear primary cancer locations or advanced-stage diseases, aiding in the detection of distant metastases.

Treatment / Management

Early-stage cancers (stage I or II) typically undergo single-modality therapy, which may involve surgery (excision of the primary tumor with margins along with elective or therapeutic neck dissection) or radiation therapy (targeting the primary tumor site and at-risk nodal basins of the neck). Primary surgery offers improved local control and reduced morbidity in oral cavity cancers compared to non-surgical treatments, which is not often seen in other head and neck cancer sites.[14]

Late-stage cancers (stage III or IV), on the other hand, necessitate multimodality therapy. Surgical intervention may be followed by radiation therapy (with or without chemotherapy or immunotherapy) or a combination of chemotherapy and immunotherapy, as well as radiation therapy.

Surgery

The extent of surgical intervention is contingent upon factors such as tumor size, location, and stage. Typically, it involves a wide local excision with an oncologic margin. Tumors affecting the tongue are treated with glossectomy, which can be partial or total. Tumors located in the buccal mucosa or soft palate are managed with wide local excision, while tumors of the hard palate require maxillectomy. Mandibular alveolar tumors are addressed with wide local excision and mandibulectomy; marginal mandibulectomy suits superficial tumors, whereas segmental mandibulectomy is reserved for deep or advanced tumors. Lip tumors are managed with wide local excision or wedge excision.

If there is evidence of local invasion or lymph node spread, neck dissection may be indicated or recommended electively. In cases of high-risk but clinically negative neck nodes, sentinel lymph node biopsy is also a viable option. Histological examination of excised tumors is crucial to confirm clear margins. Occasionally, a temporary tracheostomy may be necessary to ensure a safe airway after surgery, particularly following upper airway swelling. Reconstruction may be required in more extensive resections, which can involve regional or free tissue transfer techniques.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is a primary treatment modality used alongside surgery and chemotherapy or immunotherapy. This targets the primary tumor site and any nodal basins at risk for metastasis. However, radiation in the head and neck region often results in significant mucositis, leading to odynophagia and potential nutritional challenges. Patients may require alternate feeding methods, such as a nasogastric tube or formal gastrostomy, for an extended period. Long-term effects of radiation may include taste alterations, mucosal dryness, and esophageal strictures or motility changes, which can sometimes be permanent.

Chemotherapy

The cornerstone of treatment for head and neck cancer involves platinum-based chemotherapy, such as cisplatin or carboplatin. Chemotherapy is not used as a standalone curative treatment but rather in conjunction with radiation therapy. Additionally, chemotherapy is commonly utilized as an adjunct to palliative care interventions.

Immunotherapy

Cetuximab, an epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor, can be combined with radiotherapy for treatment. Additionally, monoclonal antibodies such as pembrolizumab target specific genetic receptors on tumor cells. Tumors must be tested to assess the target receptor expression and determine the suitability of monoclonal antibody treatment. This approach is commonly applied to locally advanced, recurrent, or metastatic diseases. Similar to chemotherapy, immunotherapy is not used as a standalone curative treatment but is valuable for palliative care interventions.[15]

Palliation

When aggressive or advanced tumors or significant comorbidities prevent curative treatment, a palliative approach is the most suitable option for patients. This typically includes palliative radiotherapy alongside anticipatory medications aimed at symptom management and optimizing end-of-life care.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for oral mucosal lesions should include the conditions mentioned below.

- Pre-cancerous lesions: Erythroplakia and leukoplakia.

- Benign oral mucosal lesions: Geographic tongue, median rhomboid glossitis, necrotizing sialometaplasia, hairy tongue, oral hairy leukoplakia, oral candidiasis, herpetic gingivostomatitis, aphthous ulcers, traumatic ulcers, herpes labialis.

- Benign tumors: Papilloma, lipoma, lingual thyroid, mucocele, ranula, neurofibroma, haemangioma, oral keratoacanthoma

- Odontogenic tumors

Staging

Staging

Tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) staging is crucial for categorizing tumors, predicting prognosis, and devising treatment plans. This staging system integrates clinical, histological, and radiological assessments, focusing on the primary tumor, neck lymph nodes, and distant metastases. In 2017, The American Joint Committee on Cancer published changes in the 8th edition of the Cancer Staging Manual on TNM classification for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers, aiming to improve differentiation between these 2 cancer types.[16]

T Classification

- T1: Tumor size ≤2 cm and DOI ≤5 mm

- T2: Tumor size 2 to 4 cm and DOI ≤10 mm or tumor size ≤2 cm and DOI 5 to 10 mm

- T3: Tumor size >4 cm or any tumor with a DOI >10 mm

- T4a: Tumor invades through the cortical bone of the mandible or maxillary sinus, or it invades the skin of the face

- T4b: Tumor invades the masticator space, pterygoid plates, or skull base, or it encases the internal carotid artery

N Classification

Clinical

- NX: Regional node involvement cannot be assessed

- N0: No LN involved

- N1: Single ipsilateral LN, ≤3 cm in size

- N2a: Single ipsilateral LN, >3 cm to ≤6 cm in size

- N2b: Multiple ipsilateral LNs, all ≤6 cm in size

- N2c: Any bilateral or contralateral LNs, all ≤6 cm in size

(All of the above have no extranodal involvement, ENE(-))

- N3a: LN size >6 cm and ENE(-)

- N3b: Any LN with ENE(+) involvement, either clinically or radiographically

Pathological

- N1-N2: Same criteria as above and ENE(-) with the exceptions of the following:

- N2a: LN size ≤3 cm and ENE(+)

- N3a: LN size >6 cm and ENE(-)

- N3b: LN size ≥3 cm and ENE(+) LN, or >1 ENE(+) LNs

M Classification

- M0: No distant metastases can be observed

- M1: Distant metastases can be observed

DOI: Depth of invasion

ENE: Extranodal extension

ENE(+): Extranodal extension present

ENE(-): Extranodal extension absent

LN: Lymph node

Prognosis

Prognosis and survival rates in cancer depend significantly on the stage at diagnosis, timely and appropriate treatment, and the expertise of local healthcare providers. Patients' 5-year survival rates decrease notably when the disease spreads locally and even further if distant metastases develop. These trends underscore the critical importance of early detection and diagnosis in improving outcomes and survival rates.

The American Cancer Society estimates concurrent survival rates for oral and oropharyngeal cancers. The 5-year survival rate is approximately 84% for individuals with localized disease. However, this rate decreases to 66% and 39% for those with regional and distant spread of the disease, respectively. Notably, HPV-positive disease generally leads to higher survival rates.

Due to many statistics being grouped with oropharyngeal cancer, particularly with its higher incidence of HPV-positive cancers, determining precise survival rates for oral cavity cancer alone is challenging. However, it's known that tumor recurrence is prevalent with oral squamous cell carcinoma, occurring at the primary site, in the lymph nodes, or as distant metastases in organs such as the lungs, liver, or bone.[17] Recurrence is associated with significantly high mortality rates, and early recurrence is typically indicative of a poorer prognosis.

Complications

Complications in oral mucosal cancer can arise from untreated disease progression or commonly from the adverse effects of treatment interventions. Surgical procedures, such as tumor excision, neck dissection, and free flap reconstruction, carry inherent risks, which include flap failure, wound dehiscence, damage to local motor and sensory nerves, vocal cord paralysis, trismus, dysarthria, and potential long-term reliance on tracheostomy and/or feeding tubes. These complications may necessitate an extended stay in intensive care for some patients.

Chemotherapy or radiotherapy can lead to a diverse array of debilitating and chronic symptoms. In the context of oral mucosal cancer, patients frequently encounter mucositis (inflammation of the mucosa), pain, bleeding, trismus, and dry mouth. These symptoms, coupled with dysphagia, can result in reduced oral intake and malnutrition. Speech difficulties are common, necessitating therapy from speech and language teams. Additionally, the systemic effects of treatment may induce neutropenia, increasing the risk of infections due to compromised immunity.

The psychological ramifications of a cancer diagnosis, coupled with the aforementioned complications and treatment adverse effects, can have devastating and life-long effects on mental well-being and overall quality of life. Studies indicate that approximately 50% of head and neck cancer patients experience depression, underscoring the significant mental health challenges faced by individuals dealing with this condition.[18]

Deterrence and Patient Education

The primary strategy for preventing oral cancer revolves around lifestyle modifications to mitigate key risk factors. Providing guidance on smoking cessation, educating individuals about safe alcohol consumption levels, and promoting balanced nutrition are crucial. These efforts not only serve as an important public health message to prevent the incidence of oral cancer but also play a vital role in helping diagnosed patients prevent cancer recurrence.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A multidisciplinary team approach of healthcare professionals is indispensable for diagnosing, investigating, and treating patients with oral mucosal cancer. Primary care and dental professionals are crucial in identifying early pre-cancerous changes or tumors and referring patients to secondary care. Radiologists play a vital role in interpreting imaging studies and performing ultrasound-guided biopsies to aid in diagnosis. Surgical evaluation, planning, and procedures often involve a collaborative effort among otolaryngologists and maxillofacial and plastic surgeons. Histopathologists contribute significantly to the accurate diagnosis and staging of the disease. Additionally, oncologists provide specialized expertise in designing and administering chemoradiotherapy treatments.

Cancer nurse specialists are crucial in coordinating care and serving as the initial point of contact for patient support and guidance. Following treatment, various healthcare professionals are involved in surveillance for disease recurrence. Multidisciplinary meetings are essential for discussing individual patient cases and developing comprehensive strategies to ensure positive outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Renou A, Guizard AV, Chabrillac E, Defossez G, Grosclaude P, Deneuve S, Vergez S, Lapotre-Ledoux B, Plouvier SD, Dupret-Bories A, Francim Network. Evolution of the Incidence of Oral Cavity Cancers in the Elderly from 1990 to 2018. Journal of clinical medicine. 2023 Jan 30:12(3):. doi: 10.3390/jcm12031071. Epub 2023 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 36769722]

Uguru CC, Chukwubuzor O, Otakhoigbogie U, Ogu UU, Uguru NP. Awareness and knowledge of risk factors associated with oral cancer among military personnel in Nigeria. Nigerian journal of clinical practice. 2023 Jan:26(1):73-80. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_322_22. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36751827]

Rivera C. Essentials of oral cancer. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology. 2015:8(9):11884-94 [PubMed PMID: 26617944]

Lee YC, Marron M, Benhamou S, Bouchardy C, Ahrens W, Pohlabeln H, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Agudo A, Castellsague X, Bencko V, Holcatova I, Kjaerheim K, Merletti F, Richiardi L, Macfarlane GJ, Macfarlane TV, Talamini R, Barzan L, Canova C, Simonato L, Conway DI, McKinney PA, Lowry RJ, Sneddon L, Znaor A, Healy CM, McCartan BE, Brennan P, Hashibe M. Active and involuntary tobacco smoking and upper aerodigestive tract cancer risks in a multicenter case-control study. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2009 Dec:18(12):3353-61. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0910. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19959682]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRochefort J, Karagiannidis I, Baillou C, Belin L, Guillot-Delost M, Macedo R, Le Moignic A, Mateo V, Soussan P, Brocheriou I, Teillaud JL, Dieu-Nosjean MC, Bertolus C, Lemoine FM, Lescaille G. Defining biomarkers in oral cancer according to smoking and drinking status. Frontiers in oncology. 2022:12():1068979. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1068979. Epub 2023 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 36713516]

Gandini S, Botteri E, Iodice S, Boniol M, Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Boyle P. Tobacco smoking and cancer: a meta-analysis. International journal of cancer. 2008 Jan 1:122(1):155-64 [PubMed PMID: 17893872]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKumar M, Nanavati R, Modi TG, Dobariya C. Oral cancer: Etiology and risk factors: A review. Journal of cancer research and therapeutics. 2016 Apr-Jun:12(2):458-63. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.186696. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27461593]

Jafarey NA, Mahmood Z, Zaidi SH. Habits and dietary pattern of cases of carcinoma of the oral cavity and oropharynx. JPMA. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 1977 Jun:27(6):340-3 [PubMed PMID: 413946]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCandotto V, Lauritano D, Nardone M, Baggi L, Arcuri C, Gatto R, Gaudio RM, Spadari F, Carinci F. HPV infection in the oral cavity: epidemiology, clinical manifestations and relationship with oral cancer. ORAL & implantology. 2017 Jul-Sep:10(3):209-220. doi: 10.11138/orl/2017.10.3.209. Epub 2017 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 29285322]

Kruse AL, Grätz KW. Oral carcinoma after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation--a new classification based on a literature review over 30 years. Head & neck oncology. 2009 Jul 22:1():29. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-1-29. Epub 2009 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 19624855]

Ferrándiz-Pulido C, Leiter U, Harwood C, Proby CM, Guthoff M, Scheel CH, Westhoff TH, Bouwes Bavinck JN, Meyer T, Nägeli MC, Del Marmol V, Lebbé C, Geusau A. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients With Advanced Skin Cancers-Emerging Strategies for Clinical Management. Transplantation. 2023 Jul 1:107(7):1452-1462. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000004459. Epub 2023 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 36706163]

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2018 Nov:68(6):394-424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. Epub 2018 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 30207593]

Montero PH, Patel SG. Cancer of the oral cavity. Surgical oncology clinics of North America. 2015 Jul:24(3):491-508. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2015.03.006. Epub 2015 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 25979396]

Tsai CY, Wen YW, Lee SR, Ng SH, Kang CJ, Lee LY, Hsueh C, Lin CY, Fan KH, Wang HM, Hsieh CH, Yeh CH, Lin CH, Tsao CK, Fang TJ, Huang SF, Lee LA, Fang KH, Wang YC, Lin WN, Hsin LJ, Yen TC, Cheng NM, Liao CT. Early relapse is an adverse prognostic factor for survival outcomes in patients with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma: results from a nationwide registry study. BMC cancer. 2023 Feb 7:23(1):126. doi: 10.1186/s12885-023-10602-1. Epub 2023 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 36750965]

Naruse T, Yanamoto S, Matsushita Y, Sakamoto Y, Morishita K, Ohba S, Shiraishi T, Yamada SI, Asahina I, Umeda M. Cetuximab for the treatment of locally advanced and recurrent/metastatic oral cancer: An investigation of distant metastasis. Molecular and clinical oncology. 2016 Aug:5(2):246-252 [PubMed PMID: 27446558]

Kato MG, Baek CH, Chaturvedi P, Gallagher R, Kowalski LP, Leemans CR, Warnakulasuriya S, Nguyen SA, Day TA. Update on oral and oropharyngeal cancer staging - International perspectives. World journal of otorhinolaryngology - head and neck surgery. 2020 Mar:6(1):66-75. doi: 10.1016/j.wjorl.2019.06.001. Epub 2020 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 32426706]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang B, Zhang S, Yue K, Wang XD. The recurrence and survival of oral squamous cell carcinoma: a report of 275 cases. Chinese journal of cancer. 2013 Nov:32(11):614-8. doi: 10.5732/cjc.012.10219. Epub 2013 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 23601241]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNoel CW, Sutradhar R, Chan WC, Fu R, Philteos J, Forner D, Irish JC, Vigod S, Isenberg-Grzeda E, Coburn NG, Hallet J, Eskander A. Gaps in Depression Symptom Management for Patients With Head and Neck Cancer. The Laryngoscope. 2023 Oct:133(10):2638-2646. doi: 10.1002/lary.30595. Epub 2023 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 36748910]