Introduction

The axillary approach to the brachial plexus nerve block was first described by Dr. Halstead et al. in 1884. Before the prevalence of ultrasound, its superficial location and low risk of complications, such as pneumothorax, made it a useful block for outpatient hand surgery. Its superficial location allows for easier identification of the individual nerve branches with a nerve stimulator or ultrasound techniques. Of note, contrary to its name, this block does not block the axillary nerve and should not be confused with the relatively newer axillary nerve block.[1][2] For the remainder of this article, the discussion will only address the axillary approach to the brachial plexus.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Review of Brachial Plexus Anatomy

The brachial plexus is a network of neural tissue that starts from the lower cervical to upper thoracic spinal nerve roots and ultimately ends with terminal nerves that innervate the entire upper extremity. The plexus arises from the ventral primary rami of the C5, C6, C7, C8, and T1 nerve roots with small contributions from C4 and T2.

The cervical roots course between the two layers of prevertebral fascia that separate to invest the middle and anterior scalene muscle bodies. At this point, the brachial plexus lies between the bellies of these two muscles and has formed into the three trunks of the brachial plexus.

The C5, C6 nerve roots join to form the superior trunk, which sends off a branch called the suprascapular nerve. The C7 root continues as the middle trunk, while the C8 and T1 roots join to form the inferior trunk.

The superior, middle, and inferior trunks each separate into dorsal and ventral divisions posterior to the subclavian artery. These six divisions will soon regroup distally into three cords around the axillary artery, which is a continuation of the subclavian artery beyond the lateral border of the first rib until the teres major muscle. The dorsal divisions of the middle and superior trunks create the lateral cord, while the dorsal division of the lower trunk continues as the medial cord. The ventral divisions of superior, middle, and inferior trunks join to form the posterior cord. The cords derive their names based on their positional relationship to the axillary artery.

Finally, the terminal branches of the brachial plexus arise from the cords at the lateral border of the pectoralis minor muscle. The musculocutaneous nerve is a branch of the lateral cord. The ulnar nerve is a branch of the medial cord. The lateral and medial cords join to form the median nerve. Other branches of the medial cord include the median cutaneous nerve of the arm and the median cutaneous nerve of the forearm. The posterior cord gives rise to axillary and radial nerves. Other branches of the posterior cord are the subscapular and thoracodorsal nerve.[3][4]

Surface Anatomy for the Axillary Approach

The axilla is a pyramid-shaped space inferior to the glenohumeral joint and superior to the axillary fascia with the base of the pyramid on the surface. The apex of the axilla is the cervico-medullary canal bounded by the clavicle, first rib, and upper part of the scapula. The pectoralis major and minor muscles, and pectoral and clavipectoral fascia form the anterior wall. The scapular and subscapularis muscle in the upper part and latissimus dorsi and teres major muscles in the inferior part make up the posterior wall. The first four ribs and associated intercostal and serratus anterior muscles comprise the medial wall. The humeral head and neck comprise the lateral wall of the axilla.

Pertinent surface anatomy landmark for nerve stimulator-based techniques is the pulse of the axillary artery just distal to the pectoralis major near the anterior axillary wall. Superior to this point, one can identify the coracobrachialis muscle for the associated musculocutaneous nerve block.[5]

Sonoanatomy for the Axillary Approach

Sonoanatomy of the brachial plexus in the axilla readily reveals the axillary artery and the surrounding hypoechoic nerves inside the fascia. With the ultrasound probe placed longitudinally at the mid to distal axilla: the median nerve may be identified lateral and superficial to the axillary artery, the ulnar nerve is typically medial and superficial to the artery, and the radial nerve location is posterior to the artery. There is, however, variation to the exact nerve location around the artery.[6] The musculocutaneous nerve is usually found within the fascial plane between the biceps and coracobrachialis muscles or piercing the coracobrachialis muscle belly.

Indications

This block reliably covers procedures on the elbow, forearm, and hand. However, without the additional musculocutaneous block, then there may be inadequate forearm coverage as there would be sparing of the anterolateral distribution.

This block would not be suitable for true axillary procedures.

Contraindications

Infection at the injection site in the axilla or patient refusal is an absolute contraindication for using this block.

Preexisting nerve damage, including numbness, paresthesia, or motor weakness, may be a relative contraindication. These symptoms should be assessed and documented before doing any block as there may be an increased risk for nerve injury. Anticoagulation and severe pulmonary disease may also be relative contraindications.

Equipment

- Sterile gloves

- Standard nerve block tray including chlorhexidine prep, a 3-ml syringe with lidocaine 1% with a 25-gauge needle

- A local anesthetic in a syringe (20-25 ml of ropivacaine 0.5% or bupivacaine 0.5%)

- 5-cm, 20-gauge short-bevel insulated needle (either stimulating or non-stimulating)

- Ultrasound machine with a linear transducer (8-14 MHz), sterile sleeve, and ultrasound gel

Personnel

Apart from the person performing the nerve block, an additional person is needed to inject the local anesthetic.

Preparation

As with any procedure, informed consent is a strong recommendation before the performance of the nerve block.

Before any regional anesthetic technique, standard patient monitoring should be in place: continuous electrocardiography, pulse oximetry, and blood pressure. Intravenous access and available IV fluid should be ready. Immediate availability of resuscitation equipment (i.e., an oxygen source, resuscitation bag, airway devices) and medications (i.e., vasopressors, 20% lipid emulsion) should be confirmed.

Optimal patient positioning for this nerve block using the ultrasound technique requires arm abduction to access the axilla. The arm should be abducted at least 90 degrees. The forearm may be propped comfortably, whether supported horizontally at 90 degrees or above or behind the head.

Technique or Treatment

Several studies have shown that the ultrasound-guided axillary approach is quicker, more successful, has a lower incidence of complications, and requires a lower total dose of local anesthetic. Hence, the authors will describe the ultrasound technique of the axillary brachial plexus nerve block. Due to the widespread adoption of ultrasound guidance in the United States, the authors will not discuss other techniques.[7][8][9]

Assuming the operator is cephalad to the patient’s arm, they will then palpate the insertion point of the pectoralis major muscle in the anterior axilla. Just distal to this muscle, the ultrasound transducer is placed in the longitudinal plane to visualize the cross-section of the axillary vessels and nerves in the arm.

The axillary vein is visualized medial to the artery. Care must be taken not to avoid compressing the axillary vein causing it to be obliterated from view. Inability to visualize the vein while performing the nerve block may cause inadvertent vascular puncture or intravascular local anesthetic injection.

At the author’s institution, an in-line technique is preferable, with the needle inserted in a superior to inferior direction. Before insertion of the block needle, a skin wheal of lidocaine 1% is created for patient comfort. The radial, median, and ulnar nerves are targeted around the axillary artery at a relatively superficial depth of usually 1 or 2 centimeters. Recall that this compartment subdivides via fibrous septa, and proximity of the needle to the targeted nerves is essential for the nerve block to work.

The musculocutaneous nerve is in the fascial plane between the biceps brachii and coracobrachialis muscles or within the belly of the coracobrachialis muscle. The block needle may remain at the same entry point and simply be redirected towards that fascial plane between the two muscles or inside the coracobrachialis muscle belly to block the musculocutaneous nerve. If the musculocutaneous nerve is not blocked, sparing of the anterolateral forearm will occur.

Throughout the procedure, the operator should use safe practices, including divided administration of local anesthetic and aspiration prior to injection to confirm negative heme to avoid intravascular administration and avoiding injection against high injection pressure or if a patient reports paresthesia. It is highly recommended to withdraw the needle until the paresthesia subsides and then redirect.[10][6]

Complications

Following complications are possible, but their incidence is low:

- Infection

- Bleeding or hematoma formation

- Nerve injuries, such as neuropraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis

- Inadvertent intravascular injection

- Local anesthetic systemic toxicity

Clinical Significance

Because of its distance from the phrenic nerve, the axillary approach may have a reduced likelihood of phrenic nerve palsy that may occur more frequently with the interscalene and subclavian approaches. For patients with severe pulmonary disease or contralateral hemidiaphragmatic paresis, the axillary approach is probably preferable.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Peripheral nerve blocks are a team effort. The regionalist, as well as the nursing and support staff, are all essential in helping to maintain the highest standards of care. Hemodynamic monitors should always be applied, and nursing staff should make sure emergency drugs and equipment should be easily accessible to the clinician performing the procedure. As with any other regional technique, the risk of local anesthetic systemic toxicity is always present, so 20% lipid emulsion should be immediately available. Meticulous records of the procedure and administered medications should are requisite. The operating room nurse should work with the procedural clinician to coordinate the recording of the steps. Pharmacists should review the choice of medications and check for drug interactions and contraindications. Clear, organized, and succinct communication with other members of the patient's care team should be the norm. Once the procedure is completed, nurses will need to monitor vital signs and report to the clinician should there be any abnormalities. This interprofessional approach will result in the best outcomes. [Level V]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

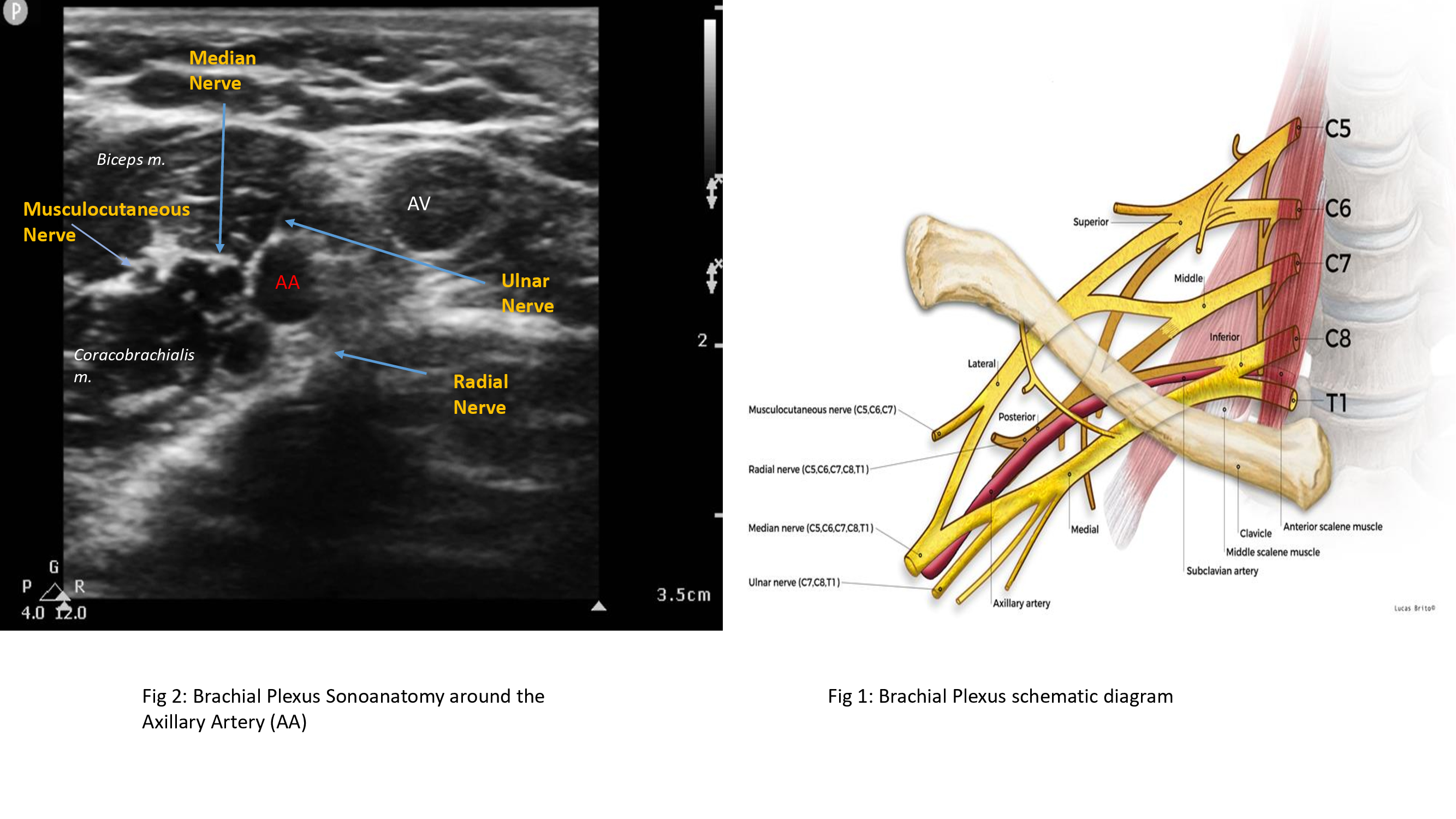

Brachial Plexus Ultrasound and Schematic Diagram. The left image shows an ultrasonographic view of the brachial plexus, while the right image shows the nerve plexus' schematic diagram and anatomic relationships. Labeled structures in the ultrasound image include the median, musculocutaneous, radial, and ulnar nerves; the axillary artery and vein; and the biceps and coracobrachialis muscles. Labeled structures in the schematic diagram include the vertebrae C5 to T1; the superior, middle, and inferior trunks of the plexus; the lateral, posterior, and medial cords of the plexus; the musculocutaneous, radial, median, ulnar, and axillary nerves; the clavicle; the subclavian artery; and the anterior and middle scalene muscles.

Contributed and Created by Muhammad Salman Janjua, with Permission from Lucas Brio

References

DE JONG RH. Axillary block of the brachial plexus. Anesthesiology. 1961 Mar-Apr:22():215-25 [PubMed PMID: 13720553]

BOSOMWORTH PP, EGBERT LD, HAMELBERG W. Block of the brachial plexus in the axilla: its value and complications. Annals of surgery. 1961 Dec:154(6):911-4 [PubMed PMID: 13871605]

Orebaugh SL,Williams BA, Brachial plexus anatomy: normal and variant. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2009 Apr 28 [PubMed PMID: 19412559]

Gili S, Abreo A, GóMez-Fernández M, Solà R, Morros C, Sala-Blanch X. Patterns of Distribution of the Nerves Around the Axillary Artery Evaluated by Ultrasound and Assessed by Nerve Stimulation During Axillary Block. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2019 Jan:32(1):2-8. doi: 10.1002/ca.23225. Epub 2018 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 30341965]

Feigl G, Aichner E, Mattersberger C, Zahn PK, Avila Gonzalez C, Litz R. Ultrasound-guided anterior approach to the axillary and intercostobrachial nerves in the axillary fossa: an anatomical investigation. British journal of anaesthesia. 2018 Oct:121(4):883-889. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.06.006. Epub 2018 Aug 23 [PubMed PMID: 30236250]

Berthier F, Lepage D, Henry Y, Vuillier F, Christophe JL, Boillot A, Samain E, Tatu L. Anatomical basis for ultrasound-guided regional anaesthesia at the junction of the axilla and the upper arm. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2010 Mar:32(3):299-304. doi: 10.1007/s00276-009-0539-2. Epub 2009 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 19669074]

Chan VW, Perlas A, McCartney CJ, Brull R, Xu D, Abbas S. Ultrasound guidance improves success rate of axillary brachial plexus block. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d'anesthesie. 2007 Mar:54(3):176-82 [PubMed PMID: 17331928]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceQin Q, Yang D, Xie H, Zhang L, Wang C. Ultrasound guidance improves the success rate of axillary plexus block: a meta-analysis. Brazilian journal of anesthesiology (Elsevier). 2016 Mar-Apr:66(2):115-9. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2015.01.002. Epub 2015 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 26952217]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZhu W, Zhou R, Chen L, Chen Y, Huang L, Xia Y, Papadimos TJ, Xu X. The ultrasound-guided selective nerve block in the upper arm: an approach of retaining the motor function in elbow. BMC anesthesiology. 2018 Oct 19:18(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12871-018-0584-7. Epub 2018 Oct 19 [PubMed PMID: 30340524]

Satapathy AR, Coventry DM. Axillary brachial plexus block. Anesthesiology research and practice. 2011:2011():173796. doi: 10.1155/2011/173796. Epub 2011 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 21716725]