Introduction

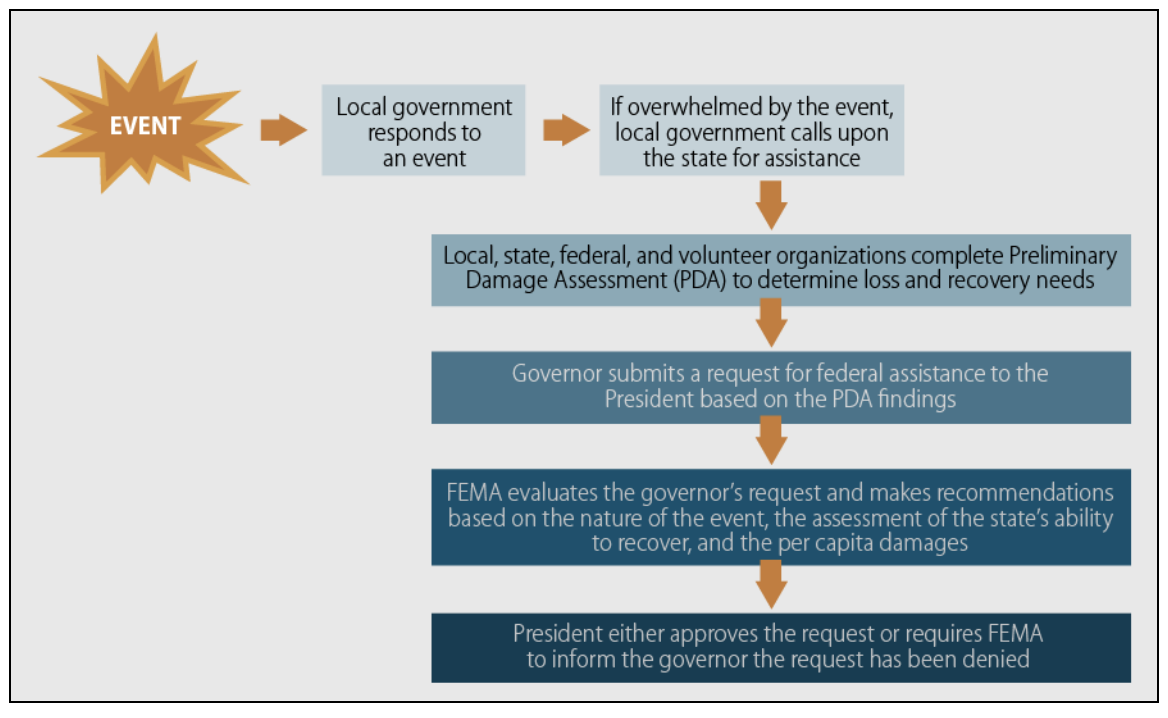

A disaster, as defined by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), is "a non-routine event that exceeds the capacity of the affected area to respond to it in such a way as to save lives; to preserve property; and to maintain the social, ecological, economic, and political stability of the affected region." When a disaster occurs, the Stafford Act allows the state governor or tribal leader (hereafter "governor") of the affected area to petition the President of the United States for a disaster declaration, which mobilizes federal resources to augment local resources in the aftermath of the disaster. Local and state resources are expected to be able to manage the first 72 hours of an incident, after which federal resources can support and augment local efforts but not supplant them (See Image. The Stafford Act Process for Declaring Emergencies and Major Disasters).

After the Disaster

In the aftermath of a disaster, the local response includes the following:

- Providing first responder resources

- Activating the Emergency Operations Center and Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan

- Coordinating the response with local agencies

- Communicating with and submitting Situation Reports (SITREPS) to the state agency

- Utilizing regional mutual aid agreements

- Activating state and federal response agreements

- Announcing a state of emergency

- Request aid from the State Emergency Management Agency

The state's responsibility following a disaster includes evaluating SITREPS, response efforts and requests for Assistance provided by locales, activating the State Emergency Operations Center, and determining whether federal Assistance is needed. The state governor may also proclaim a "State of Emergency," which will put into motion the state disaster preparedness plan that allows for activating state resources and requests for federal resources through the Stafford Act or other applicable federal programs if needed.

Once a disaster has occurred and it is apparent that the area’s recovery needs outweigh the scope of local resources, the governor will contact their local FEMA office to request a joint federal-state and tribal preliminary damage assessment (PDA). This assessment should outline how and why the provincial government resources are inadequate to address the local disaster. In conjunction with local representatives, the federal team assesses the affected area to determine the extent of the disaster, who and what public resources are affected, and what federal Assistance will be needed. The request for disaster declaration must be made through the local FEMA office within 30 days of the disaster.

The Process of Disaster Declaration

After completing the PDA, the governor may petition the President via the regional FEMA office for a disaster declaration. Concurrently, the governor should execute the region’s emergency plan. He or she is responsible for detailing what local resources are committed to disaster relief, estimating the damage to public and private sector assets, and estimating what resources are needed under the Stafford Act.

Once federal Assistance has been approved, FEMA will activate the Federal Response Plan and assign a federal coordinating officer to lead the Emergency Response Team. This team works directly with the state coordinating officer to provide a coordinated response to local and state needs. They will also activate the Federal Response Plan, which coordinates federal agencies and the American Red Cross relief efforts. Additionally, FEMA will start a Washington-based Emergency Support Team to monitor ongoing efforts.

FEMA disaster assistance may include the following types of Assistance:

- Individual and household assistance

- Individuals and Households Program

- Crisis Counseling Program

- Disaster Case Management

- Disaster Unemployment Assistance

- Disaster Legal Services

- Disaster Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

- Public Assistance

- Debris removal

- Emergency protective measures

- Roads and bridges

- Water control facilities

- Buildings and equipment

- Utilities

- Parks, recreational, and other facilities

- Hazard Mitigation Assistance

- Reimburses state and local governments and nonprofit organizations for actions taken to mitigate or prevent long-term loss of life from natural hazards

Types of Disaster Declarations

There are 2 types of Disaster Declarations under the Stafford Act: Emergency Declarations and Major Disaster Declarations. They differ in the kind of disaster and scope of Assistance provided. For either type of disaster declaration, the governor must demonstrate that the prescribed emergency plan has been executed and describe the local and state resources already employed to address the disaster, as enumerated in the PDA.

Emergency Declarations are employed for any situation where federal Assistance is needed. Assistance may not exceed $5 million unless the president seeks additional approval by Congress. State or Tribal governments may request a pre-disaster declaration when there are imminently anticipated needs before the event. Under this type of declaration, the federal government may provide limited resources. There are 2 types of Assistance under this program: Public and Individual. States or Tribal Governments are not prohibited from seeking a Major Disaster Declaration if the needs of the locale exceed the resources provided by the Emergency Declaration. For an Emergency Declaration, the governor must describe other federal agency resources already utilized and how much additional federal Assistance is required.

Major Disaster Declarations can be made for any naturally occurring disaster or, regardless of cause, any damage caused by fire, explosions, or floods when it is estimated that damages will outstrip local and state resources. Relief can include public and individual emergency assistance and permanent work. For a Major Disaster Declaration, the regional leader must submit with their request the estimated cost of the disaster to the local private and public sector, estimates of how much Assistance is needed from the Stafford Act, and the governor must certify that they will comply with applicable cost-sharing requirements.

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

Because "all disasters are local," individuals and locales are expected to be wholly self-sufficient following a disaster for 72 hours. This sustenance includes food, water, shelter, medication, and other personal or local necessities. Once federal resources are deployed, they are intended to supplement, but not replace, local resources, and local governments maintain control of all assets used for disaster response. National and local disaster recovery assets (including specially trained personnel and equipment) can, and should be, deployed and staged before imminent disasters so that recovery response is promptly accessible to the areas most affected.

Generally, disaster response is thought to be directly proportional to the need generated by the disaster. However, evaluating responses to Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria revealed that Puerto Rico was not equitably compensated in the aftermath of each disaster when compared to Florida and Houston. Disproportionate compensation decreases health equity in the wake of a disaster.[1] Public health is difficult to manage under ideal circumstances; efforts have been made worldwide to create frameworks for public health disaster preparedness and response that encompass community needs, ethics, and values.[2] For example, in Riverside County, California, Public Health and Emergency Management officials developed an ethical framework for their disaster response plan using community ethics and values to address potential inequities during disaster response. Multiple community stakeholders were involved in reviewing and implementing the plan to ensure that care disparities were not made even worse in the disaster response process.[3]

Resiliency is another concept that has been promulgated in disaster research. Disaster recovery starts with disaster preparation. Communities that treat disaster response along a continuum of time that begins before disasters happen have better long-term health and recovery after disasters occur.[4]

Clinical Significance

Community resilience research has shown that all community members, including individuals, businesses, and private and nonprofit agencies, should participate in disaster preparedness. Community outreach and education are required to educate and engage the community in mitigating damage and recovering from disasters that will inevitably occur.[5]

Recovery after a disaster is more challenging for children, older people, those with disabilities, and complex mental and physical health needs. Nearly half of the US population is described as potentially vulnerable in the aftermath of a disaster.[6] Previously, disaster recovery efforts have not accommodated the needs of this vulnerable population.[7] Lessons learned from prior disasters have informed changes to response efforts which account for those with specific health needs, including involving community-based organizations who represent vulnerable groups in disaster planning, disseminating information to communities on various platforms to consider for those who are blind or deaf and the potential use of Telehealth to evaluate and treat patients remotely.[8][9]

During a disaster event, an interprofessional approach to the community's health needs must be in place, where physicians, mid-level practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other qualified personnel (eg, EMTs) work collaboratively in an "all hands on deck" fashion. This collaboration can help bring about the best resolution for the community as a whole and the individuals in the community with their particular requirements.

Local health departments have an opportunity for improvement as well. After Hurricane Harvey's recovery, local health departments in the impacted area were asked about their response to the needs of citizens in their area. There was wide variability among health departments' engagement with the local population. There was poor communication between health departments and other health sectors. Opportunities to increase resources, technical help, and communication between health sectors were identified as ways to improve response and community resilience.

Hospitals, too, as large healthcare providers and community members, are obligated to prepare for disaster response and have increasingly developed plans to most effectively address the needs of a potentially large influx of patients during a disaster response. Community Health Care coalitions have been proposed to join local healthcare stakeholders in knowledge and resource-sharing in the event of a community disaster.[10]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Willison CE, Singer PM, Creary MS, Greer SL. Quantifying inequities in US federal response to hurricane disaster in Texas and Florida compared with Puerto Rico. BMJ global health. 2019:4(1):e001191. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001191. Epub 2019 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 30775009]

Khan Y, O'Sullivan T, Brown A, Tracey S, Gibson J, Généreux M, Henry B, Schwartz B. Public health emergency preparedness: a framework to promote resilience. BMC public health. 2018 Dec 5:18(1):1344. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6250-7. Epub 2018 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 30518348]

Kaiser C, Leon R, Craven K. Process of Development of a County-wide Crisis Care Plan - Riverside County, California, 2016-7. PLoS currents. 2018 Oct 1:10():. pii: ecurrents.dis.f272fef04c7222a546e03450221a69d1. doi: 10.1371/currents.dis.f272fef04c7222a546e03450221a69d1. Epub 2018 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 30345155]

2015 Sep 10; [PubMed PMID: 26401544]

Kennedy M, Gonick S, Meischke H, Rios J, Errett NA. Building Back Better: Local Health Department Engagement and Integration of Health Promotion into Hurricane Harvey Recovery Planning and Implementation. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2019 Jan 23:16(3):. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16030299. Epub 2019 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 30678041]

Mace SE, Doyle CJ. Patients with Access and Functional Needs in a Disaster. Southern medical journal. 2017 Aug:110(8):509-515. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000679. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28771647]

Stough LM, Sharp AN, Resch JA, Decker C, Wilker N. Barriers to the long-term recovery of individuals with disabilities following a disaster. Disasters. 2016 Jul:40(3):387-410. doi: 10.1111/disa.12161. Epub 2015 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 26577837]

Nick GA, Savoia E, Elqura L, Crowther MS, Cohen B, Leary M, Wright T, Auerbach J, Koh HK. Emergency preparedness for vulnerable populations: people with special health-care needs. Public health reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974). 2009 Mar-Apr:124(2):338-43 [PubMed PMID: 19320378]

Uscher-Pines L, Fischer S, Chari R. The Promise of Direct-to-Consumer Telehealth for Disaster Response and Recovery. Prehospital and disaster medicine. 2016 Aug:31(4):454-6. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X16000558. Epub 2016 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 27216971]

Walsh L, Craddock H, Gulley K, Strauss-Riggs K, Schor KW. Building health care system capacity to respond to disasters: successes and challenges of disaster preparedness health care coalitions. Prehospital and disaster medicine. 2015 Apr:30(2):112-22. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X14001459. Epub 2015 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 25658909]