Introduction

Simulation has become an integral component of modern medical education. As healthcare simulation has become a mainstream educational modality for adult learners, simulation centers are faced with the challenge of financial sustainability. Simulation centers and simulation-based training programs can be costly to build and maintain and require substantial long-term investment from their affiliated organization(s). While simulation has been shown to improve patient outcomes, funding for training and education is finite, and understanding and justifying these costs can be challenging.[1][2] Being able to clearly articulate the costs, as well as the clinical and economic benefits of a simulation-based training program, will provide the organization with data needed to support their decision to invest in simulation-based training.[3]

Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Function

Costs associated with deployment and operation of a simulation center often are broadly summarized as “stuff, staff, and space.” Direct costs are what typically come to mind when considering the cost of a simulation program. Initial costs such as the design and engineering of space that the center is to be built in, the actual material and construction cost of building the space, acquisition of computers, software, mannequins, stretchers, and consumable materials would be considered direct costs. Salaries considered direct costs are those that typically directly support a program and include faculty stipends, standardized patients, and simulation operations specialists to support educational events.

Indirect costs include operational overhead such as administrative support and salaries, cost of utilities, insurance, and depreciation of the building and facilities. Items such as office supplies and consumables not directly invoiced to learner groups would also fall into this category. Some indirect costs unique to the simulation include the cost per use of equipment and simulators, simulator warranties, and equipment repair. Salaries typically considered indirect costs vary depending on the scale and needs of the center and may include a director stipend, administrative assistants, security personnel, custodians, education specialists, and research support staff.

Another way to consider cost when operationalizing a simulation program is to consider opportunity costs. These are the “lost opportunities,” when resources or time could be used elsewhere, such as the time a clinician-educator spends outside of clinical practice or the operating room, or the revenue that could be generated from using the simulation center space for other activities.

All of these should be considered when developing an annual cost cycle for the center and can be considered for individual educational programs as well. An annual cost cycle should be calculated to ensure the sustainability of the simulation center. There is a multitude of economic evaluations to demonstrate the effectiveness of dollars spent. A full economic evaluation is to be used when there are two or more alternatives are being considered and if both outcomes and cost data are available and considered. Without complete information or with limited alternatives, a partial evaluation can be used. This partial evaluation would look at either outcomes or costs.

Common Cost Examples

Staff:

Full-time staff cost (Sim Ops), Standardized Patients, and expert instructors are the most common direct staff expenses. Other things to consider when hiring clinical staff are ongoing professional development and replacing expert instructor clinical time. There are substantial personnel costs with running a successful high-quality simulation that must be considered upfront. Smaller simulation programs may consider outsourcing personnel to remain cost-effective.

Stuff:

High fidelity simulation requires the “stuff” to be in good working order for all learners. Significant costs are incurred when obtaining new equipment such as ultrasound machines, task trainers, radiology equipment, computers, video monitors, network infrastructure, and software. It is also important to recognize associated recurring costs such as maintenance costs, cost of consumables, and the ability to recycle supplies for another purpose. When purchasing large items like mannequins and task trainers, it is also important to consider the warranty and anticipated longevity. All of these factors help determine what the supply cost will be for a given course. This information can then be used in the financial analysis discussed above. If cadavers are implemented into the +simulation, there are other laws that need to be taken into consideration. Donated tissue is protected from generating a profit; however, storage and handling fees are acceptable.

Space:

The discussion of space will depend highly on the needs and budget of a given institution. Space of a simulation can be provided by an institution, it can be rented, or it can be purchased. The range of costs cannot be generalized, but generalizable items are the cost per square foot, maintenance, and associated utilities. Standard utilities such as electric are a consideration, but it is also important to factor in medical-related utilities such as medical gas, large unit refrigeration, negative pressure and etc.

Cost Cycle Example

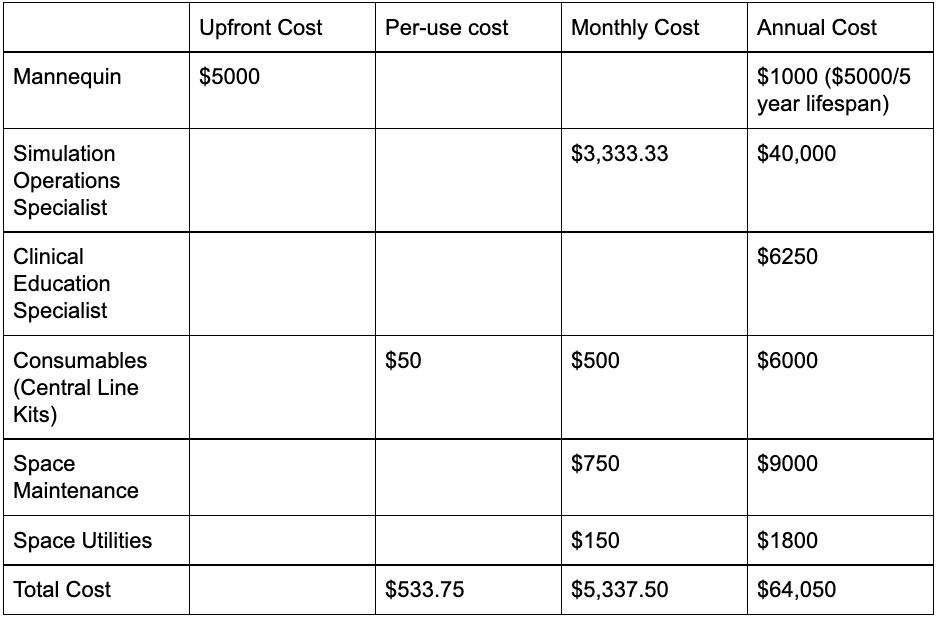

An annual Cost Cycle will encompass a complete evaluation of a simulation center. For a simple example, let’s consider a cost cycle of a simulation center that performs 1 central line course a month to a group of 10 learners. For this example, our simulation space will be 200sq/ft, 1 simulation operations specialist, 1 clinical education specialist, 10 learners, 1 reusable mannequin, 10 disposable pieces.

Direct Costs will be identified first. For this example, they include Simulation Employee Salary, Reusable Mannequin, and Disposable Kits. For our example, our employee is paid $40k annually, the mannequin costs $5000, and central line kits are $50. For this example, the mannequin will have a useful life of 5 years, and the simulation space will have been paid for.

In this example, the indirect costs are clinical time lost by the subject matter expert/clinician-educator, rent for simulation space, maintenance of simulation space, and utilities of simulation space. A way to quantify qualitative indirect costs such as educators' lost clinical time can be estimated using several methods. One simple method would be to take the annual salary of a full-time clinician and then calculate the lost income based on hours. For our example, let’s assume that a course takes 4 hours a month to run. Over the course of a year, our expert clinician gives up 48 hours of clinical time to teach. If he would otherwise work 160hrs a month, he would be giving up 2.5% of his clinical time (4/160). A full-time clinician may otherwise make $250,000 per year. Since he is giving up 2.5% of his time, the opportunity cost for this physician educator would be $6,250 (0.025 x $250,000).

The table outlines the total cost of this one class annually (see Image. Cost Analysis Example). This rudimentary cost cycle identified a total cost of $64,050 annually to provide a central line course to 10 learners a month. By dividing the annual cost by 12, the monthly cost is then determined to be $5,337.50. Since in this example, there is 1 course per month with 10 learners, we are able to calculate the total cost per learner to be $533.75. This information can then be used for strategic planning moving forward.

The information contained in an annual cost cycle can be as detailed as needed for a given center. A cost analysis can be done on any subcategory and can be evaluated on a course by course or even instructor by instructor basis. This information can help predict expenses for the following year if there are significant differences in costs and resources utilized by different instructors.

Revenue [6]

Funding a simulation center is a complex endeavor. Funding can be thought of as two components, initial investment, and continued revenues. When analyzing revenue streams, it is also important to factor in the difference between the predicted and actual revenues. Well-functioning simulation centers enjoy varying revenue streams to achieve financial sustainability. When developing a strategic plan for a simulation center, it is crucial to identify internal and external streams of revenue. Having diverse sources of revenue improves the sustainability of a center.

Internal Streams

Institution-based simulation centers benefit from having several stakeholders for the success and sustainability of the center. It is important to balance the utilization of simulation training within an institution with its direct and opportunity cost of doing outside business. Internal revenue streams come in many forms. A simulation center can offer a cost to the university upfront, based on the course, charging departments for use. Some centers function on a hybrid model, offering courses to the university at cost or close to cost and diversify revenue streams by having an alternative industry rate for private consumers. Some centers may be blessed with donors. Depending on the scale of the donor pool, a center may have an endowment. A center may be partially or completely funded by an endowment. This endowment may have constraints as to how to spend funding when dealing with internal vs. external stakeholders.

External Streams

Simulation centers offer several opportunities with the private sector. A given center can partner with local private industry such as a medical device manufacturer to provide classes using high fidelity simulation. There are opportunities for contracts with outside hospital systems such as private hospitals or with EMS. Educational courses are another potential source of revenue and can be hosted for a region.

Grants

Innovative simulation centers can be opportunities for several education funds, from grants for simulation research. To private grants given by donors provide opportunities for revenue and expansion of the simulation center brand.

Cost savings

Although difficult to appreciate in the beginning stages of simulation center development and planning, cost savings are important when determining return on investment. Examples of cost savings that can occur with the implementation of simulation training are malpractice insurance rate reductions, reduction in lost revenue from catheter-associated urinary tract infections or central line-associated bloodstream infections, and cost savings broadly associated with reduced medical errors (length of stay, infection rates, adverse events).

Directly, the costs of consumables and other large purchases can be mitigated with bulk purchasing if available. During annual reviews, it is important to identify opportunities for high-utilization components and opportunities for bulk discounts. Working in tandem with a hospital or institution may help in improving the cost-per-item of consumables.

Burril, S, Kane A. Deloitte 2017 survey of US health system CEOs: Moving forward in an uncertain environment. Deloitte Center for Health Solutions. (2017)

When determining return on investment, the literature has identified 3 components that should be considered in order to determine the value of simulation training. As demonstrated above, it can be difficult to realize the value of simulation training as it consists of several intangible assets. A model for determining the return on investment of simulation training was developed to reflect these unique challenges. (Bukhari et al.) The components described are costs, qualitative benefits, and quantitative benefits.

Cost

As mentioned above, costs include development cost, maintenance cost, operation cost, labor cost, and materials cost.

Quantitative Benefits

Generally, quantitative benefits are more easily measured. Quantitative benefits include time savings, error reduction, time to competence, equipment breakage costs, reduction in alternative training, and procedures performed. These factors were described by Frost and Sullivan and implemented into an ROI tool specifically for calculating ROI for computer-based simulation.

Qualitative Benefits

When calculating return on investment, measuring qualitative benefits is often the most difficult to convert to monetary value. The work of Phillips and Phillips describes a framework to estimate the effectiveness of training programs. Used in simulation, this framework can be used to support the expansion or continuation of a given training program. Their framework is dependent on feedback from participants themselves and functions on the assumption that “participants are capable of determining how much improvement is related to the actual training program.”

After these components have been identified, the framework for calculating ROI begins with value measurement methodology (VMM). This methodology was developed by the office of social security to identify the qualitative and quantitative effects of regulations. A blueprint was then published in 2002, which allowed the VMM framework to be applied to various projects. For the purposes of simulation, Bukhari et al. described the following 5 value categories:

- Direct value—benefit of simulation in training users (e.g., PGY1 trainees, etc.)

- Social value—the benefit to society (e.g., quality of care, fewer complications, etc.)

- Operational value—decrease in length of stay

- Strategic value—patient safety culture, sustainability

- Financial value—increase revenue, reduce costs.

In some cases, a program may generate no revenue but aligns with the strategic plan of the center or provides a marketing opportunity.

It is also important to keep the mission statement of the center in mind when considering new revenue streams.

Phillips JJ, Phillips PP. Show Me the Money: How to Determine ROI in People, Projects, and Programs. 1st ed. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2007.

Barriers to Sustainability [8][9]

Designing, constructing, and maintaining can be an expensive endeavor. Once a simulation center is functioning and costs and funding are identified, the next step is focussing on sustainability. As a simulation center grows, this adds pressure to become cost-neutral to the organization and to justify existing costs. One of the common barriers encountered is what users and events should be prioritized. For institution-based simulation centers, a diversity of learners equates to a diversity of revenue streams which may benefit the bottom line of a center. On the other hand, adding outside revenue streams may conflict with the utilization of the space by internal stakeholders. The decision to please an external stakeholder over an internal stakeholder should come with careful analysis of the situation. Another common pitfall early in planning is underestimating indirect costs. Underestimating indirect costs can lead to significant budget issues moving forward, especially when confronted with unexpected losses. This reiterates the critical importance of a thorough and well-planned cost cycle. It is also important to have discussions with other simulation center leaders to ensure an accurate representation of estimated indirect costs, especially in the early stages of developing a simulation center.

Another barrier often overlooked is competition. When a center is built, it may be the only one offering educational experiences in a region or in a particular type of educational experience. To stay competitive, a center must balance operating costs with the broader market cost of the services provided. Even if there are no similar offerings for simulation-based training in a given region, there will be a point where outside organizations will find it more cost-effective to bring certain components of service or simulation in-house. Once another organization has the resources to train in-house, they may begin offering that training to the broader community, thus increasing the competition in that region.

The last anticipated barrier that should be considered is technology costs. As new technology emerges, this may lead to an enriched simulation experience, which can be demanded by clients and directors alike. Constantly buying new technology comes at a significant startup cost. This cost includes the technology itself, the cost to train staff, the cost to implement, the potential need for new ancillary technologies to augment the experience, and downtime to areas of the center while these new technologies are installed and tested. Implementing new technologies must be done with a broad strategy in mind. Some questions to consider: Does this new technology improve learning? Can I justify the increased cost-per-use to my clients? Will this technology significantly improve in the near future?

While this short list covers some barriers to sustainability, it is important to be aware of the unanticipated. For example, a hospital-funded simulation center may experience budget cuts from its parent organization for a myriad of reasons. If the simulation center has no diversity in its funding, it will be unable to sustain itself if the larger parent organization needs to pull back funds. This is an important concept for not just institution-dependent centers but also institution-independent centers. A loss of a revenue stream can occur to any center. A single revenue stream center opens itself to significant liability in bearish economic times or when that single funding source is strained.

Clinical Significance

Simulation is a complex and growing field to educate all levels of healthcare providers and student learners. Understanding the fundamentals of a financially sustainable simulation program is critical to the long-term success of the program.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Typically, an interprofessional team approach consisting of clinicians, nurses, and business administrators is necessary to arrange the financing necessary to fund the development of a simulation learning center.

Media

References

Murphy M, Curtis K, McCloughen A. What is the impact of multidisciplinary team simulation training on team performance and efficiency of patient care? An integrative review. Australasian emergency nursing journal : AENJ. 2016 Feb:19(1):44-53. doi: 10.1016/j.aenj.2015.10.001. Epub 2015 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 26614537]

Okuda Y, Bryson EO, DeMaria S Jr, Jacobson L, Quinones J, Shen B, Levine AI. The utility of simulation in medical education: what is the evidence? The Mount Sinai journal of medicine, New York. 2009 Aug:76(4):330-43. doi: 10.1002/msj.20127. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19642147]

Asche CV, Kim M, Brown A, Golden A, Laack TA, Rosario J, Strother C, Totten VY, Okuda Y. Communicating Value in Simulation: Cost-Benefit Analysis and Return on Investment. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2018 Feb:25(2):230-237. doi: 10.1111/acem.13327. Epub 2017 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 28965366]

Maloney S, Haines T. Issues of cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness for simulation in health professions education. Advances in simulation (London, England). 2016:1():13. doi: 10.1186/s41077-016-0020-3. Epub 2016 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 29449982]

Fletcher JD, Wind AP. Cost considerations in using simulations for medical training. Military medicine. 2013 Oct:178(10 Suppl):37-46. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00258. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24084304]

Fahey P, Cruz-Huffmaster D, Blincoe T, Welter C, Welker MJ. Analysis of downstream revenue to an academic medical center from a primary care network. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2006 Aug:81(8):702-7 [PubMed PMID: 16868422]

Bukhari H, Andreatta P, Goldiez B, Rabelo L. A Framework for Determining the Return on Investment of Simulation-Based Training in Health Care. Inquiry : a journal of medical care organization, provision and financing. 2017 Jan:54():46958016687176. doi: 10.1177/0046958016687176. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28133988]

Hailemariam M, Bustos T, Montgomery B, Barajas R, Evans LB, Drahota A. Evidence-based intervention sustainability strategies: a systematic review. Implementation science : IS. 2019 Jun 6:14(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0910-6. Epub 2019 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 31171004]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceQayumi K, Pachev G, Zheng B, Ziv A, Koval V, Badiei S, Cheng A. Status of simulation in health care education: an international survey. Advances in medical education and practice. 2014:5():457-67. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S65451. Epub 2014 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 25489254]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence