Introduction

The esophagus is an approximately 25-cm muscular tube that connects the pharynx to the stomach. Histologically, it consists of several layers—the innermost mucosal layer, the submucosal layer (which connects the mucosa to the muscular layer), the outer muscular layer, and the adventitial layers. The submucosal layer contains blood vessels, the Meissner nerve plexus, and the esophageal glands.

Intramural hematoma of the esophagus, also known as dissecting intramural hematoma, is a rare manifestation of acute mucosal and submucosal injuries resulting in an interlayer blood collection. The condition can occur spontaneously or secondary to trauma from a foreign body, ingestion of toxic substances, or iatrogenic interventions. Patients may present with symptoms that mimic other acute cardiopulmonary diseases. The classic triad of symptoms associated with intramural hematoma of the esophagus includes acute chest pain, odynophagia or dysphagia, and hematemesis. Prognosis is usually excellent with proper diagnosis and management.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The proposed mechanism involves a rapid alteration in intrathoracic and intraesophageal pressures triggered by events such as vomiting, retching, and coughing, leading to the formation of an intramural hematoma that may rupture into the esophageal lumen. Additionally, the use of anticoagulants, antiplatelet medications, and coagulopathic disorders are associated with the development of intramural esophageal hematoma. In certain cases, intramural esophageal hematoma can occur spontaneously without an identifiable cause.[4]

Intramural hematoma of the esophagus can be associated with various etiologies and broadly classified as either spontaneous or secondary to trauma and iatrogenic procedural interventions. Secondary causes include traumatic ingestion of foreign bodies, Valsalva maneuver, lifting heavy weights, hurried large bulky bolus swallowing, nasogastric tube insertion, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, endotracheal intubation, and transesophageal echocardiogram, as documented mainly in case reports in the literature.[5][6][7][8][9][10]

Epidemiology

Esophageal traumatic injuries, including traumatic penetration and perforation, are rare, making it challenging to estimate the incidence or prevalence of intramural hematoma of the esophagus.[11] Most incidents have been reported in case reports. A large case series review notes a bimodal age distribution, with peaks around the ages of 45 and 75. Intramural hematoma of the esophagus is more commonly observed in older females, who are twice as likely to develop this condition compared to males, for reasons that are not yet understood.

Patients with underlying coagulopathy disorders, such as hemophilia or inpatients taking antiplatelet or anticoagulant medications, are at higher risk of developing both spontaneous and secondary intramural hematoma of the esophagus.[12] Although the development of this entity is rare, it is increasingly being recognized early due to the widespread availability of modern radiological and endoscopic facilities.[13][14][15]

Pathophysiology

In patients with normal blood clotting, vomiting can lead to the formation of a submucosal hematoma, typically in the lower esophagus. This suggests that the pressure from vomiting can damage the mucosa and submucosal vessels. In a reported case, the esophageal submucosal hematoma was located on the right anterior wall of the distal esophagus—an area prone to increased intra-abdominal pressure. Initially forming in the lower esophagus, the hematoma likely resulted from mucosal laceration, leading to bleeding and collapse. This bleeding from ruptured submucosal vessels likely extended into the upper esophagus, resulting in a widespread esophageal submucosal hematoma.[16]

A sudden pressure change in the esophagus and an underlying bleeding tendency have been proposed as mechanisms of spontaneous intramural hematoma of the esophagus. Secondary intramural hematoma of the esophagus is thought to result from an acute injury similar in mechanism to a Mallory-Weiss tear and Boerhaave syndrome, with the intramural hematoma representing an intermediate stage. The proposed initiating cause for the development of this condition is sudden bleeding between the mucosa and muscularis propria of the esophageal wall, sometimes involving a long segment of the esophagus. This progressive submucosal dissection due to bleeding leads to symptoms ranging from severe pain to signs of esophageal lumen obstruction. Later, a breach of the mucosa containing the hematoma can occur, presenting as hematemesis.[15]

History and Physical

Intramural hematoma of the esophagus usually presents as a sudden onset of chest or retrosternal pain. Most patients (80%) present with at least 2 of the classical triad of symptoms—retrosternal chest pain (84%), dysphagia or odynophagia (59%), and hematemesis (56%). While taking the patient's history, it is important to inquire about any bleeding diathesis or anticoagulation medication. A history of violent retching, vomiting, or instrumentation of the esophagus may also be present. Rarely, a history of foreign body ingestion is present.

Physical examination may only reveal nonspecific findings such as tachycardia and pallor. In addition, it is crucial to distinguish esophageal hematoma from other causes of acute chest pain. The presence of dysphagia or odynophagia can help exclude significant cardiac causes of retrosternal pain.[17]

Evaluation

Multiple modalities have been used to diagnose this condition.[18] The preferred primary investigation is a computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous contrast. This noninvasive technique can be performed quickly and is available in most centers. The typical CT finding is a thickened esophageal wall with luminal compression or, in large hematomas, obliteration of the lumen. An intraesophageal mass or filling defect may be visualized, sometimes resembling a double-barrel or dual lumen.

A contrast-enhanced CT will delineate the anatomical relationship between the esophagus, aorta, and mediastinal structures. Often, the contrast study of the esophagus will demonstrate a smooth filling defect in the lumen of the esophagus. Administration of oral contrast and imaging should be performed when transmural perforation is suspected. The extravasation of oral contrast extraluminally is diagnostic and can demonstrate the location of the rent in the mucosa.

Other investigative modalities, such as endoscopic ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), can help diagnose intramural hematoma of the esophagus. Endoscopy should be postponed until the integrity of the esophageal wall has been established. If needed, an endoscopy can be performed with care after confirming the integrity of the esophageal wall. An endoscopy will reveal a bluish swelling with or without a mucosal tear. Endoscopic ultrasound is superior to conventional endoscopy because it can demonstrate submucosal lesions and evaluate adjacent structures. MRI can show a mass of intermediate density on T1- and T2-weighted images, distinguishing intramural hematoma of the esophagus from other mediastinal pathologies and displaying soft tissue planes around the aorta.

An electrocardiogram (ECG), chest radiograph, and cardiac markers are useful in excluding other cardiopulmonary diseases. The presence of pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, or pleural effusion should raise a strong suspicion of a transmural injury to the esophagus and an intramural hematoma.

A proposed grading of the degree of luminal involvement by the hematoma includes:

- Stage I: Isolated hematoma

- Stage II: Hematoma surrounded by tissue edema

- Stage III: Hematoma causing compression of the esophageal lumen

- Stage VI: Obliteration of the esophageal lumen by the hematoma [10]

Treatment / Management

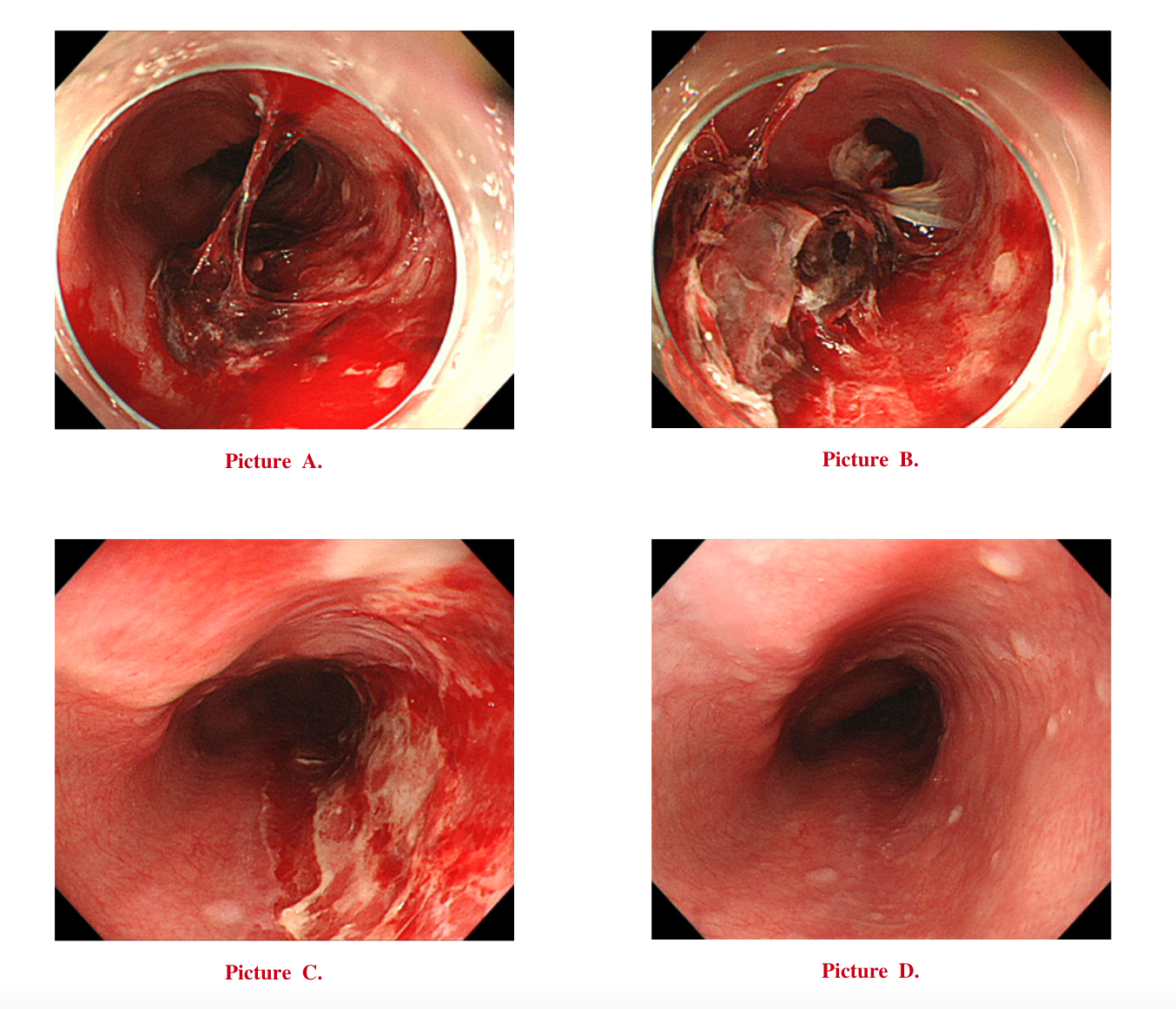

Treatment for intramural hematoma of the esophagus is usually conservative. Initial management involves withholding oral intake, administering intravenous fluids, correcting any associated coagulopathy, and administering proton pump inhibitors. Serial CT scans or contrast swallow studies are needed to monitor clinical progress and hematoma resolution. The patient is gradually allowed oral feeding as symptoms improve. In most cases, medical and conservative treatment typically result in the complete recovery of patients (see Image. Progression and Healing Stages of Esophageal Hematoma).

Recurrent bleeding or increased difficulty swallowing should raise suspicion for hematoma leakage or rupture into the esophageal lumen and expanding hematoma, respectively. This situation should be managed as an acute emergency with airway protection and hemodynamic resuscitation. Therapeutic angiography may become necessary in cases of recurrent massive hematemesis to stop bleeding and hematoma expansion via transarterial embolization. Surgery, typically associated with poor outcomes, may be necessary for patients who do not respond to conservative therapy or who experience massive recurrent hemorrhage leading to hemodynamic instability or severe esophageal luminal obstruction or perforation.[19][20][21][22][18](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

During the initial presentation of a patient with suspected intramural hematoma of the esophagus, it is essential to consider all acute cardiothoracic emergencies in the differential diagnosis. Classic differentials include Mallory-Weiss syndrome (mucosal tear) and Boerhaave syndrome (transmural perforation), as intramural hematoma of the esophagus can be an intermediate stage between these two conditions. While a history of severe vomiting often precedes Mallory-Weiss and Boerhaave syndromes, it is not a reliable factor for exclusion.

A chest x-ray may reveal pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, or pleural effusion in cases of Boerhaave syndrome. Acute retrosternal chest pain is also common in acute myocardial infarction, aortic dissection, and pulmonary embolism, which should be ruled out through careful history-taking, physical examination, and appropriate diagnostic tests. Hematemesis and dysphagia or odynophagia in intramural hematoma of the esophagus can help differentiate it from other critical conditions when used alongside other diagnostic modalities.[22]

Once an accurate diagnosis is established, appropriate treatment should be administered based on the patient's specific symptoms and condition. Treatment options for spontaneous intramural hematoma of the esophagus include the following:

-

Conservative treatment: This involves medical approaches such as fasting, acid suppression, hemostasis, and protection of the esophageal and gastric mucosa. This method is suitable for cases where the muscle layer is unaffected, and the hematoma can be absorbed within 1 to 3 weeks.

-

Interventional embolization: This treatment is appropriate for complications such as mediastinal hematoma or hemothorax.

-

Surgery: This is necessary in cases of esophageal rupture.[18]

Prognosis

Intramural hematoma of the esophagus is considered a benign condition, with a generally favorable prognosis when managed promptly and appropriately. Most patients fully recover with conservative treatment, including rest, pain management, and dietary modifications. Patients typically experience significant symptom relief within days to weeks, and intramural hematoma of the esophagus fully resolves in 3 to 4 weeks.[15] However, it is essential for clinicians to monitor for any signs of deterioration, especially in patients with underlying risk factors or comorbidities.

Complications

Although rare, complications of intramural hematoma of the esophagus can be severe and require prompt attention. They are mainly related to intraluminal bleeding secondary to rupture of hematoma in the esophageal lumen and expanding hematoma causing esophageal luminal obstruction. Increasing swallowing difficulty should raise suspicion of expanding hematoma. The most significant complication is esophageal perforation, which can lead to mediastinitis and sepsis and necessitate surgical intervention.

Other potential complications include secondary infection of the hematoma, stricture formation, and persistent dysphagia due to scar tissue. Additionally, there is a risk of rebleeding, especially in patients with underlying coagulopathies or those on anticoagulant therapy. Aspiration of blood or necrotic tissue into the lungs can lead to aspiration pneumonia. Early and accurate diagnosis through imaging and endoscopic evaluation is crucial to prevent complications and ensure a positive outcome. Regular follow-up and monitoring are essential to promptly detect and address any developing complications.[23]

Consultations

Patients with intramural hematoma of the esophagus often require multidisciplinary consultations to ensure comprehensive management and optimal outcomes. A gastroenterologist should be consulted for diagnostic evaluation and endoscopic management. Consultation with a cardiothoracic surgeon is essential, particularly if there is concern for esophageal perforation or other complications requiring intervention. The expertise of a radiologist is crucial for interpreting imaging studies such as CT scans and ensuring accurate diagnosis. If the patient has a coagulopathy or is on anticoagulant therapy, the involvement of a hematologist is necessary to manage these conditions effectively.

Additionally, a dietitian may be needed to assist with nutritional modifications during the recovery phase. In cases of significant pain or distress, consultation with a pain management specialist or psychologist may be beneficial. This collaborative approach ensures that all aspects of the patient's condition are addressed, promoting swift and complete recovery.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with intramural hematoma of the esophagus must adhere to dietary restrictions and undergo serial imaging follow-up to prevent complications. They should be educated about symptoms such as difficulty swallowing, blood in vomit, dark stool, or melena to promptly diagnose complications. Efforts should be directed to avoid activities that can increase intraesophageal pressure or trauma, such as heavy weightlifting, Valsalva maneuvers, and abrupt swallowing of large food boluses, which otherwise can exacerbate symptoms and incite complications. Patients taking antiplatelet or anticoagulant medications for other reasons should closely follow up with their physician regarding the safe resumption of these medications.

Pearls and Other Issues

Intramural hematoma of the esophagus is a rare but acute condition, often occurring in patients with bleeding tendencies or those on anticoagulation therapy. This condition is more frequently observed in individuals who have undergone esophageal instrumentation or experienced traumatic mucosal injury, although spontaneous cases can also occur. With an aging population at increased cardiovascular risk and on anticoagulants, early recognition and diagnosis of intramural hematoma of the esophagus are crucial. Misdiagnosing intramural hematoma of the esophagus as a cardiopulmonary condition can lead to dangerous complications, particularly if anticoagulation or thrombolytic therapy is administered inappropriately. Accurate diagnosis and appropriate management are essential to prevent such outcomes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of intramural hematoma of the esophagus requires a collaborative, interprofessional approach to ensure patient-centered care, enhance outcomes, and promote patient safety. Each healthcare professional plays a critical role, contributing unique skills and perspectives to the team. Physicians and advanced practitioners must possess strong diagnostic skills to promptly identify intramural hematoma of the esophagus and be proficient in interpreting imaging studies and endoscopic findings. Nurses play a vital role in patient care by closely monitoring vital signs, administering medications, and providing patient education and support. Pharmacists are crucial in managing anticoagulation therapy and recommending alternatives to prevent exacerbation of the condition.[24][21]

Coordinated care involving gastroenterologists, surgeons, radiologists, hematologists, dietitians, pain management specialists, and psychologists is crucial for the comprehensive management of intramural hematoma of the esophagus. Implementing evidence-based treatment strategies and protocols ensures consistent and effective care. This collaborative approach facilitates timely interventions, continuity of care, and thorough follow-up.

Regular training, simulations, and debriefings optimize team performance to address challenges and improve protocols, a critical need given the rarity of intramural hematoma of the esophagus. Interprofessional and multidisciplinary problem-solving and decision-making skills within the healthcare team can enhance overall performance and patient care for individuals affected by intramural hematoma of the esophagus.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Yamada T, Motomura Y, Hiraoka E, Miyagaki A, Sato J. Nasogastric Tubes Can Cause Intramural Hematoma of the Esophagus. The American journal of case reports. 2019 Feb 20:20():224-227. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.914133. Epub 2019 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 30783075]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMandavdhare HS, Gupta P, Maity P, Sharma V. Image Diagnosis: Esophageal Intramural Hematoma in Sudden-Onset Chest Pain and Dysphagia. The Permanente journal. 2018:23():18-141. doi: 10.7812/TPP/18-141. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30589409]

Chu L, Yang JS, Yu KX, Chen CM, Hao DJ, Deng ZL. Usage of Bone Wax to Facilitate Percutaneous Endoscopic Cervical Discectomy Via Anterior Transcorporeal Approach for Cervical Intervertebral Disc Herniation. World neurosurgery. 2018 Oct:118():102-108. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.07.070. Epub 2018 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 30026139]

Hamada Y, Aota T, Nakagawa H. Intramural Esophageal Hematoma. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2024 Mar 4:():. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.3117-23. Epub 2024 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 38432958]

Wong YM, Makmur A, Lau LC, Ting E. Temporal Evolution of Intramural Esophageal Dissection with 3D Reconstruction and Cinematic Virtual Fly-Through. Journal of radiology case reports. 2018 Feb:12(2):11-17. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v12i2.3288. Epub 2018 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 29875986]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCiuc D, Birlă R, Panaitescu E, Tanţău M, Constantinoiu S. Zenker Diverticulum Treatment: Endoscopic or Surgical? Chirurgia (Bucharest, Romania : 1990). 2018 Mar-Apr:113(2):234-243. doi: 10.21614/chirurgia.113.2.234. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29733017]

Mata Caballero R, Oteo Domínguez JF, Mingo Santos S, Garcia Touchard A, Goicolea Ruigómez J. Large dissecting intramural haematoma of the oesophagus and stomach and major gastro-oesophageal bleeding after transoesophageal echocardiography during transcatheter aortic valve replacement procedures. European heart journal. Cardiovascular Imaging. 2018 Aug 1:19(8):955. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jey058. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29659787]

Wang AY, Riordan RD, Yang N, Hiew CY. Intramural haematoma of the oesophagus presenting as an unusual complication of endotracheal intubation. Australasian radiology. 2007 Dec:51 Suppl():B260-4 [PubMed PMID: 17991080]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZippi M, Hong W, Traversa G. Intramural hematoma of the esophagus: An unusual complication of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. The Turkish journal of gastroenterology : the official journal of Turkish Society of Gastroenterology. 2016 Nov:27(6):560-561. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2016.16417. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27852551]

Cao DT, Reny JL, Lanthier N, Frossard JL. Intramural hematoma of the esophagus. Case reports in gastroenterology. 2012 May:6(2):510-7. doi: 10.1159/000341808. Epub 2012 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 23730267]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRibeiro T, Mascarenhas Saraiva M, Afonso J, Brozzi L, Macedo G. Predicting Factors of Clinical Outcomes in Patients Hospitalized after Esophageal Foreign Body or Caustic Injuries: The Experience of a Tertiary Center. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2023 Oct 25:13(21):. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13213304. Epub 2023 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 37958198]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSugimura K, Ishii N. Esophageal Hematoma Mimicking a Large Esophageal Polyp: A Diagnostic Clue of Acquired Hemophilia A. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2019 Oct:94(10):2142-2143. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.04.024. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31585586]

Ito S, Iwata S, Kondo I, Iwade M, Ozaki M, Ishikawa T, Kawamata T. Esophageal submucosal hematoma developed after endovascular surgery for unruptured cerebral aneurysm under general anesthesia: a case report. JA clinical reports. 2017:3(1):54. doi: 10.1186/s40981-017-0124-3. Epub 2017 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 29457098]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRandhawa MS, Rai MP, Dhar G, Bandi A. Large oesophageal haematoma as a result of transoesophageal echocardiogram (TEE). BMJ case reports. 2017 Nov 8:2017():. pii: bcr-2017-223278. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-223278. Epub 2017 Nov 8 [PubMed PMID: 29122910]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCullen SN, McIntyre AS. Dissecting intramural haematoma of the oesophagus. European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2000 Oct:12(10):1151-62 [PubMed PMID: 11057463]

Kanamori A, Nadatani Y, Kushiyama N, Nakata A, Higashimori A, Ominami M, Kimura T, Fukumoto S, Fujiwara Y, Watanabe T. Esophageal submucosal hematoma during transnasal endoscopy: A rare case report. DEN open. 2024 Apr:4(1):e366. doi: 10.1002/deo2.366. Epub 2024 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 38628503]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLong B, Gottlieb M. Emergency medicine updates: Upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2024 Jul:81():116-123. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2024.04.052. Epub 2024 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 38723362]

Gao F, Zhang T, Guo X, Su Z. Embolization of the esophageal branch of intercostal artery for treatment of spontaneous intramural hematoma of the esophagus: a case description. Quantitative imaging in medicine and surgery. 2023 Oct 1:13(10):7417-7422. doi: 10.21037/qims-23-564. Epub 2023 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 37869337]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChoi HK, Law S, Chu KM, Wong J. The value of neck drain in esophageal surgery: a randomized trial. Diseases of the esophagus : official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus. 2017 Nov 1:11(1):40-42. doi: 10.1093/dote/11.1.40. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29040481]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVossler JD, Abdul-Ghani A. Esophageal Hematoma following Acute Esophageal Barotrauma. The American surgeon. 2017 Jun 1:83(6):e213-215 [PubMed PMID: 28637550]

Trip J, Hamer P, Flint R. Intramural oesophageal haematoma-a rare complication of dabigatran. The New Zealand medical journal. 2017 Jun 2:130(1456):80-82 [PubMed PMID: 28571053]

Shim J, Jang JY, Hwangbo Y, Dong SH, Oh JH, Kim HJ, Kim BH, Chang YW, Chang R. Recurrent massive bleeding due to dissecting intramural hematoma of the esophagus: treatment with therapeutic angiography. World journal of gastroenterology. 2009 Nov 7:15(41):5232-5 [PubMed PMID: 19891027]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKamphuis AG, Baur CH, Freling NJ. Intramural hematoma of the esophagus: appearance on magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging. 1995:13(7):1037-42 [PubMed PMID: 8583868]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePiccione PR, Winkler WP, Baer JW, Kotler DP. Pill-induced intramural esophageal hematoma. JAMA. 1987 Feb 20:257(7):929 [PubMed PMID: 3806873]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence