Introduction

Continuous fetal monitoring, or cardiotocography, is a method of tracking the fetal heart rate (FHR) along with the occurrence of uterine contractions. The relationship between these two variables is widely accepted to correlate with the oxygenation status of the fetus. This is intended to benefit the mother and fetus by providing obstetric clinicians with additional real-time information that they may use to determine if any intervention is necessary. In many areas of the United States, continuous intrapartum fetal monitoring has been used routinely for most women undergoing labor and delivery. However, the evidence basis for this is controversial as research has demonstrated that routine FHR monitoring is associated with increases in the rates of both operative vaginal deliveries and Cesarean sections without significantly improving most newborn or childhood outcomes.[1]

Evidence is mixed on the effect of FHR monitoring on neonatal mortality, and a small reduction in the incidence of neonatal seizures has been observed when fetal monitoring is used. However, no benefit has been demonstrated from the use of fetal monitoring in most other perinatal outcomes, including Apgar scores, the incidence of neurologic injury, cerebral palsy, developmental delay, and NICU admission. Outside of the immediate intrapartum period, fetal monitoring may be used to evaluate for placental abruption, commonly when an obstetric patient presents following abdominal trauma. It may also be used to help differentiate true versus false labor. The ability to implement and interpret FHR monitoring is largely expected of obstetric care teams and is believed to serve a more important role in high-risk pregnancies and evaluation of fetal well-being outside of labor.[2]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Labor is traditionally divided into three stages. The first stage occurs from the onset of labor until complete dilation and effacement of the cervix. This stage is further divided into latent and active phases. In the latent phase, cervical change is generally slow and gradual. Once the cervix dilates to about 6 centimeters, women are considered to enter the active phase, at which time the rate of cervical change accelerates greatly.[3] This first stage of labor is also characterized by increased frequency and regularity of uterine contractions. However, because contractions may occur sporadically and cervical change may progress very slowly earlier within the third trimester, the exact onset of labor may be impossible to determine.[4] The second stage of labor occurs from complete cervical dilation to expulsion of the fetus. The third stage of labor lasts from the expulsion of the fetus until the complete expulsion of the placenta.

During the first two stages of labor, fetal circulation is subject to compression as the fetus changes position and as uterine contractions occur, and this has the potential to lead to hypoxia and/or acidosis, which may induce fetal distress predisposing to poor outcomes.[5] In monitoring the fetal status, clinicians should pay attention to the baseline fetal heart rate (FHR), variability, accelerations, and decelerations. Baseline FHR and variability are influenced by changes in CNS activity, volume status, baroreceptor stimulation, and chemoreceptor stimulation.[6]

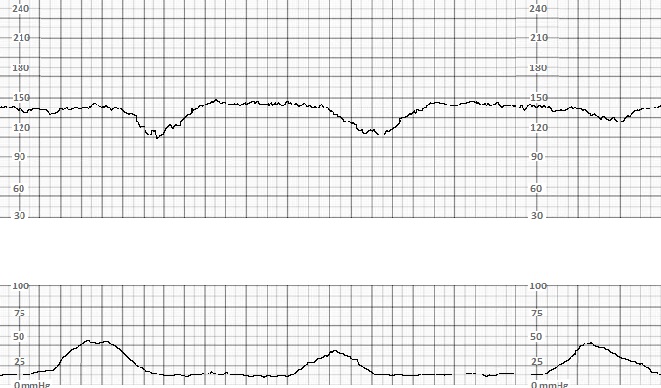

FHR accelerations are associated with fetal CNS stimulation and periods of increased fetal motor function. Early decelerations are associated with fetal head compression, particularly during uterine contractions, as increasing fetal intracranial pressure induces fetal bradycardia (see Graph. Early Decelerations). This reflex occurs rapidly, so the onset of the FHR deceleration is observed with the onset of the uterine contraction, and the nadir of the decelerations occurs at approximately the same time as the peak of the uterine contraction. Collectively, the presence of appropriate baseline FHR, variability, accelerations, and early decelerations indicates the reassuring function of fetal neurologic, autonomic, and cardiovascular systems.

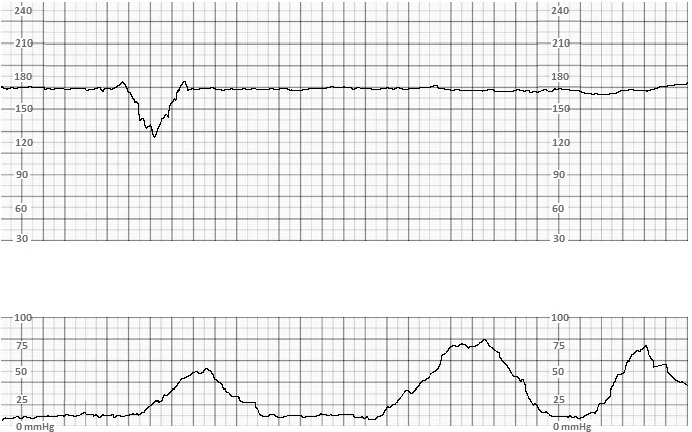

Late decelerations are thought to be related to transient fetal hypoxia (see Graph. Late Decelerations). During uterine contractions, uterine and placental blood vessels are compressed, and blood flow is reduced. In normal labor physiology, oxygenation remains adequate despite these transient decreases. However, if the baseline fetal oxygenation or perfusion is already tenuous or the magnitude of decrease in oxygenation is large enough to compromise fetal oxygenation, hypoxia occurs. Hypoxia is detected by fetal chemoreceptors that trigger reflex peripheral vasoconstriction, producing an increase in peripheral blood pressure detected by baroreceptors and ultimately producing a reflex decrease in FHR. As this sequence only begins when fetal oxygenation is sufficiently reduced and occurs in a stepwise fashion, the onset of the FHR deceleration occurs after the onset of the uterine contraction, the deceleration occurs gradually, and the nadir of the deceleration is delayed from the peak of the contraction.

Variable decelerations are associated with the umbilical cord's compression and may occur in the presence or absence of uterine contraction (see Graph. Variable Decelerations). These variable decelerations are triggered once the umbilical artery becomes compressed, resulting in arterial occlusion, decreased oxygenation, peripheral vasoconstriction, and comparatively abrupt reflex bradycardia. Late and variable decelerations both potentially indicate a predisposition to hypoxic injury and/or acidosis of the fetus and should prompt further investigation, closer observation, and potentially intervention on the part of the obstetric clinician.

The interpretation of these findings will be further discussed in the Clinical Significance section.

Indications

There is controversy regarding the appropriate implementation of intrapartum fetal monitoring. This controversy is related to the lack of evidence for improved outcomes despite increased intervention rates when FHR monitoring is used. ACOG recommends FHR monitoring for high-risk pregnancies, such as those affected by preeclampsia, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and intrauterine growth restriction.[7]

Continuous fetal monitoring may also be performed prior to the onset of labor to evaluate fetal well-being when certain pathologic states are suspected. In cases of abdominal trauma after 20 weeks' gestation, for example, a 4 to 24 hour period of fetal monitoring is recommended to assess for placental abruption.

Contraindications

There is no absolute contraindication for external FHR monitoring. However, it is not recommended for routine, low-risk pregnancies.[7] Contraindications for fetal scalp electrode monitoring include maternal HIV or active herpes simplex infections and suspected maternal or fetal coagulation disorders.[8]

Equipment

External fetal monitoring, which is most frequently used, involves the placement of two transducers placed on the maternal abdominal wall: one overlying the fetal heart to record the FHR and one over the uterine fundus to record contractions. A fetal scalp electrode may be placed when there is concern regarding the reliability of the FHR tracing, such as in the setting of significant maternal heart rate artifact. Intrauterine pressure catheters may be used in settings where external tocodynamometry is not reliable, such as maternal obesity, or in settings where precise pressure measurement is warranted, such as in protracted or arrested labor.

Complications

A 2017 meta-analysis demonstrated that women undergoing intrapartum FHR monitoring were more likely to have cesarean sections or instrumental vaginal deliveries than those assessed with intermittent auscultation.[1] Methods of internal monitoring are associated with additional complications. For example, methods invasive to the fetus such as fetal scalp electrode placement and fetal scalp pH sampling have been associated with vertical transmission of pathogens such as HSV and HIV.[9][10] They are also associated with an increased risk of scalp trauma, cephalohematoma, subdural hematoma, asphyxiation, and sepsis.[8] Intrauterine pressure catheter placement is most commonly associated with placental laceration or abruption due to malposition. However, other serious complications, including uterine perforation and cord entanglement, have been observed.[11]

Clinical Significance

As explained in the Anatomy and Physiology section, fetal monitoring conveniently and noninvasively relays real-time information regarding the neurologic, autonomic, and cardiovascular status of the fetus. Baseline FHR, variability, accelerations, and decelerations are interpreted to gain this understanding.

The normal range for baseline FHR in the perinatal period is 110 to 160, and a baseline FHR consistently in this range is reassuring.[5] The baseline FHR may be altered by intrinsic factors such as abnormal fetal cardiac pacemaking, abnormal conduction, and altered catecholamine levels. Extrinsic factors that alter the baseline FHR include maternal use of medications, fever, hypothermia, or abnormal thyroid function.

Variability is measured within a 10-minute window and is described as absent, minimal (<5 bpm), moderate (6 to 25 bpm), or marked (>25 bpm). Moderate variability is thought to be a reassuring finding as it reliably excludes significant hypoxia and acidosis. Decreased variability (absent or minimal) does not reliably indicate the presence of hypoxia or acidosis and does not reliably predict any poor perinatal outcome, although it may prompt the obstetric clinician to investigate further. The significance of marked variability is not clear.

Similarly, accelerations, which indicate fetal movement, are reassuring, but their absence is not necessarily concerning.

Early decelerations indicate a benign vagal reflex. Their presence or absence have not reliably predicted any positive or negative perinatal outcomes.

The presence of variable and/or late decelerations are potentially concerning for increased risk of poor perinatal outcomes, particularly if the decelerations are recurrent and if they are associated with decreased variability.[5]

FHR patterns are classified into three categories based on the above findings. Category I patterns must have a normal baseline FHR, moderate variability, and no variable or late decelerations (see Graph. Category I Tracing). These patterns are normal and reassure clinicians that labor may continue without intervention.

Category II patterns may involve tachycardia, bradycardia, reduced or marked variability, and/or occasional variable or late decelerations. These patterns may indicate a wide range of fetal and maternal disorders and prompt further investigation into the underlying cause and may necessitate maternal or fetal resuscitation. See Graph. Category II Tracing. If present, maternal disorders such as fever, hypothermia, dehydration, hyper- or hypothyroidism, sepsis, DKA, etc., should be identified and treated. Maternal medications should be reviewed. Maternal repositioning onto the right or left side may be attempted to improve placental perfusion. Opioids, magnesium, and beta-blockers may affect baseline FHR and/or variability, resulting in a category II pattern. Clinicians should consider the treatment of disorders such as intra-amniotic infections and oligohydramnios if suspected. The fetal sleep cycle is associated with decreased variability and may correct with fetal stimulation. Persistent abnormalities may indicate fetal arrhythmia, congenital heart defects, or antepartum neurologic injury.[12]

There is no single algorithm to manage category II FHR patterns, as the clinician must rely on history, physical examination, and other diagnostic findings to determine and address the underlying etiology. Category II patterns may resolve spontaneously to become category I, at which point no intervention is necessarily warranted. However, closer observation is needed as the pattern may deteriorate to category III.

Category III patterns include at least one of the following findings: absent variability with bradycardia, absent variability with recurrent late and/or variable decelerations, or a sinusoidal pattern. These patterns are predictive of significant hypoxia or acidosis and predispose to neurologic injury and other poor perinatal outcomes. Clinicians observing category III patterns should investigate, resuscitate, and prepare for operative delivery with urgency. Steps for resuscitation are similar to those that may be used for category II tracings and depend on the clinical scenario. Fetal stimulation and maternal repositioning may be attempted. Uterotonic medications should usually be discontinued, and tocolytics may be considered in the absence of any contraindication. Oxygen is often administered via a nonrebreather in the setting of category III tracings. However, the benefit of oxygen to a normoxic mother is unclear.[13]

Delivery should be expedited to prevent the category III pattern from persisting for greater than ten minutes, and operational vaginal delivery or Cesarean section may be performed to accomplish this goal. Note that this guideline is primarily intended to prevent poor outcomes for the newborn. Delivery may be postponed greater than ten minutes if deemed necessary for further maternal resuscitation.

As discussed above, the more ominous signs on fetal monitoring such as late decelerations, bradycardia, and decreased variability are often considered consequences of impaired fetal oxygenation and/or fetal acidosis. This also applies before the onset of labor. If a clinician is concerned about placental abruption, these findings on the fetal tracing would support the diagnosis and may warrant prompt intervention. In the setting of abdominal trauma, abnormally frequent uterine contractions are a sensitive predictor of placental abruption.[14]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Fetal monitoring is an interdisciplinary task that may improve maternal and fetal outcomes in certain settings. For optimal use, nurses and nurse-midwives should be familiar with all involved equipment and contribute by placing and troubleshooting external transducers. FHR tracings do not represent the entire clinical scenario for the mother nor the newborn, and nurses have an important role in monitoring mothers throughout labor for vital sign abnormalities, excessive discomfort, or other clinical changes that they may need to bring to the attention of a physician, nurse-midwife or another clinician on the obstetric team. These clinicians should regularly assess the FHR tracings and should initiate further diagnostic evaluation, internal monitoring, resuscitation, and/or operative delivery as appropriate. All team members should communicate effectively with the shared goal of a safe delivery for both the mother and newborn.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Alfirevic Z, Devane D, Gyte GM, Cuthbert A. Continuous cardiotocography (CTG) as a form of electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) for fetal assessment during labour. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017 Feb 3:2(2):CD006066. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006066.pub3. Epub 2017 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 28157275]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceArnold JJ, Gawrys BL. Intrapartum Fetal Monitoring. American family physician. 2020 Aug 1:102(3):158-167 [PubMed PMID: 32735438]

. Obstetric care consensus no. 1: safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2014 Mar:123(3):693-711. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000444441.04111.1d. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24553167]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHanley GE, Munro S, Greyson D, Gross MM, Hundley V, Spiby H, Janssen PA. Diagnosing onset of labor: a systematic review of definitions in the research literature. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2016 Apr 2:16():71. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0857-4. Epub 2016 Apr 2 [PubMed PMID: 27039302]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMacones GA, Hankins GD, Spong CY, Hauth J, Moore T. The 2008 National Institute of Child Health and Human Development workshop report on electronic fetal monitoring: update on definitions, interpretation, and research guidelines. Journal of obstetric, gynecologic, and neonatal nursing : JOGNN. 2008 Sep-Oct:37(5):510-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00284.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18761565]

Parer JT, Ugwumadu A. Impediments to a unified international approach to the interpretation and management of intrapartum cardiotocographs. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2017 Feb:30(3):272-273 [PubMed PMID: 27046650]

. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 106: Intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring: nomenclature, interpretation, and general management principles. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2009 Jul:114(1):192-202. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181aef106. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19546798]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKawakita T, Reddy UM, Landy HJ, Iqbal SN, Huang CC, Grantz KL. Neonatal complications associated with use of fetal scalp electrode: a retrospective study. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2016 Oct:123(11):1797-803. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13817. Epub 2015 Dec 8 [PubMed PMID: 26643181]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGoldkrand JW. Intrapartum inoculation of herpes simplex virus by fetal scalp electrode. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1982 Feb:59(2):263-5 [PubMed PMID: 7078873]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMaiques V, García-Tejedor A, Perales A, Navarro C. Intrapartum fetal invasive procedures and perinatal transmission of HIV. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 1999 Nov:87(1):63-7 [PubMed PMID: 10579618]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTrudinger BJ,Pryse-Davies J, Fetal hazards of the intrauterine pressure catheter: five case reports. British journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 1978 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 687534]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAssali NS, Brinkman CR 3rd, Woods JR Jr, Dandavino A, Nuwayhid B. Development of neurohumoral control of fetal, neonatal, and adult cardiovascular functions. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1977 Dec 1:129(7):748-59 [PubMed PMID: 24341]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGarite TJ, Nageotte MP, Parer JT. Should we really avoid giving oxygen to mothers with concerning fetal heart rate patterns? American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2015 Apr:212(4):459-60, 459.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.01.058. Epub 2015 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 25659470]

Dahmus MA, Sibai BM. Blunt abdominal trauma: are there any predictive factors for abruptio placentae or maternal-fetal distress? American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1993 Oct:169(4):1054-9 [PubMed PMID: 8238119]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence