Introduction

An analysis of the Medicare database from 2012 to 2017 revealed that nail biopsies were performed by only 0.28% of general dermatologists and 1.01% of Mohs surgeons, with cases concentrated in just 19 out of 50 states and 69 out of 929 zip codes nationally.[1] Many clinicians are reluctant to perform nail surgery procedures, often due to limited experience or training. However, for diagnostic purposes, any adequate biopsy technique—whether punch, shave, or fusiform—is preferable to avoiding a biopsy when a concerning nail lesion is present. Proper instruction and training can significantly enhance physicians' proficiency and confidence in nail surgery.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Understanding nail anatomy is crucial for performing nail surgery. The lateral horns of the nail matrix extend to the distal interphalangeal joint. Recognizing how these anatomical structures are closely related is crucial to preventing injury to these structures, which facilitates the normal functioning of the digits. The extensor tendon inserts at the distal interphalangeal joint, making it vulnerable to injury during nail surgery. Another notable anatomical landmark is the onychodermal band, where the nail bed firmly attaches to the nail plate. Familiarity with these structures ensures the proper selection and execution of nail avulsion techniques.

Indications

Nail biopsies and surgeries may be indicated for the diagnosis and treatment of various nail disorders, including longitudinal melanonychia, erythronychia, inflammatory conditions such as psoriasis and lichen planus, infections, and neoplasms of the nail unit. These neoplasms may be benign (eg, onychopapilloma, onychomatricoma, and glomus tumor) or malignant (eg, squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma). Nail procedures are critical in diagnosis, guiding treatment decisions, removing malignancies, and reducing discomfort.[2]

Contraindications

Candidates for nail surgery should be assessed for conditions that increase bleeding risk, such as anticoagulant use, and factors that could impair wound healing, including diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, or tobacco use disorder. While these factors may impact healing, they are not absolute contraindications.[3][4][5] Anticoagulation is generally not discontinued before or after nail surgery. Patients with modifiable risk factors, such as tobacco use, should be counseled on reducing or quitting tobacco use whenever possible to promote better healing.

Equipment

Several tourniquet options are available for achieving appropriate hemostasis during nail surgery, including a rolled sterile glove, Penrose drain, T-ring tourniquet, and Tourni-Cot®.[6] Recognizing the pressure differences exerted by each of these tourniquets on the digit, as most digital injuries during nail surgery result from excessive pressure on the neurovascular bundle rather than ischemia caused by tourniquet use.

A study comparing the pressures and safety profiles of various tourniquet devices, including the Penrose drain, clamped rolled glove, unclamped rolled glove, Tourni-Cot®, and T-ring tourniquet, evaluated the pressure exerted by each device. These investigations demonstrated that 500 mm Hg is the typical threshold for nerve injury and reported 31 cases of forgotten digital tourniquets in the United Kingdom from 2005 to 2009. The Penrose drain applied higher pressure than the other devices. While each method provided adequate hemostasis, only the Tourni-Cot® and T-ring tourniquet maintained safe pressure levels and hemostasis across all digit sizes.[7]

Key instruments for nail surgery that are not typically included on a standard dermatologic surgery tray include the English anvil-action nail splitter, dual-action nail nipper, and Freer periosteal elevator. The English anvil-action nail splitter has a tapered cutting edge that presses against a flat, anvil-like surface under the nail plate, utilizing a spring action system to provide increased force for more efficient cutting. The dual-action nail nipper, designed with a spring mechanism and a "double-jointed" system, enhances cutting force, making it ideal for trimming and paring thickened nails or scraping the nail unit periosteum when needed. The Freer elevator is used for precise separation or avulsion, fitting between the nail plate and the nail bed or folds. This instrument is available in flexible or rigid models with narrow or wide spatula ends. The narrow periosteal elevator, designed for pediatric use, is delicate and valuable for carefully manipulating smaller nails.

Personnel

Any healthcare professional with training in nail surgery is qualified to perform the procedure.

Preparation

Infection prevention is crucial in nail surgery. A strict sterile technique should be followed, beginning with a preoperative scrub lasting several minutes. Many surgeons use two washes, starting with alcohol followed by chlorhexidine, with or without bristled brushes, to minimize infection risk. A sterile glove or drape should cover the digit and the corresponding hand or foot. Intraoperative irrigation of the nail unit after plate avulsion has also been shown to reduce infection rates.[8]

Operating on thick nails can be challenging for the surgeon and uncomfortable for the patient. Preparing thick nails for surgery involves soaking them in soapy chlorhexidine and warm water solution for 15 to 20 minutes before the procedure. This step softens the nail plate and provides an additional layer of disinfection. Once the area is properly draped, a tourniquet is applied to the nail for optimal visualization and hemostasis (refer to the Equipment section for details). Documentation of the tourniquet application and removal times is essential.

Local anesthetics that are injected typically provide sufficient analgesia and patient comfort during outpatient nail surgery. The 3 most commonly used amide anesthetics are lidocaine, bupivacaine, and ropivacaine. Lidocaine has a rapid onset (about 3.1 minutes) with a shorter duration of action (around 2 hours) and is primarily vasodilatory. Bupivacaine, with a slower onset (7.6 minutes) and a longer duration (up to 12 hours), also acts as a vasodilator. Ropivacaine combines a quick onset (4.5 minutes) with an extended duration (up to 22 hours) and is primarily vasoconstrictive.[9]

The use of epinephrine in anesthetic mixtures for nail unit anesthesia is debated. In cutaneous surgery, epinephrine is commonly added to amide anesthetics to increase the duration of action and the anesthetic effect, as well as reduce bleeding through its vasoconstrictive properties. Although concerns have been raised about injecting epinephrine into fingers due to potential digital ischemia, studies have found these claims unsupported, noting that reported cases of digital infarction involved the simultaneous injection of either procaine or cocaine, which are known to cause ischemic complications.

Evidence suggests that epinephrine use in digits is generally safe and may reduce the need for a tourniquet, sedation, or general anesthesia.[10] However, predicting and managing epinephrine-related ischemia can be challenging. Treatment options for reversing vasoconstriction include warm water immersion, topical vasodilators, or immediate subcutaneous phentolamine injection.[11] Clinicians should note that epinephrine's vasoconstrictive effects may mask bleeding during surgery, leading some practitioners to prefer plain lidocaine, bupivacaine, or ropivacaine, as cautery is typically not used in nail surgery. Bleeding should be controlled while the patient remains in the office rather than after the effects of epinephrine wear off post-discharge. Ropivacaine is frequently preferred as a local anesthetic due to its rapid onset, prolonged duration of action, and mild vasoconstrictive properties.

Local anesthetic techniques for nail surgery analgesia include proximal digital, distal digital, transthecal digital, and distal wing blocks. Proximal, distal, and transthecal digital blocks typically require 10 to 15 minutes for anesthetic onset as the medication diffuses around the digital sensory nerves. Many surgeons favor the distal digital and distal wing blocks for their rapid onset and consistent effectiveness. The distal wing block involves injecting anesthetic into the dermis around the proximal and lateral nail folds, as well as the hyponychium.

For digital blocks, the needle is inserted at a 90° angle midway between the palmar and dorsal surfaces of the digit, either proximally between the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints or distally between the proximal interphalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints. After reaching the bone, the needle is retracted a few millimeters before injecting the anesthetic depot perpendicularly. The needle is then angled slightly toward the palmar surface for one depot and toward the dorsal surface for the final depot without fully withdrawing the needle between injections. Precise needle placement is crucial to prevent unnecessary shearing forces on the neurovascular bundle. Typically, 0.5 to 1.5 cc of anesthetic per side is used, depending on the digit's size. Surgeons should use the minimum effective volume of anesthesia to avoid ischemia due to excessive pressure on the neurovascular bundle. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Digital Nerve Block," for a more comprehensive description of a digital nerve block.

For transthecal blocks, a single depot of 1 to 2 cc is injected at a 45° angle just distal to the palmar crease into the flexor tendon sheath. This technique has a theoretical risk of tendon injury and increased pain. Alternatively, a subcutaneous block with a single depot above the flexor tendon, followed by massaging of the anesthetic, may be used.

A vibratory device and cooling ethyl chloride spray can help reduce discomfort during local anesthetic injection. A 2022 study on the impact of clinical and psychological factors on quality of life and pain severity in patients undergoing nail surgery highlighted the importance of patient comfort. Patients with high procedural pain sensitivity and anxiety reported significantly lower quality of life even 1 month after surgery, indicating the need for a comprehensive pain management plan both intraoperatively and postoperatively.[12] For patients with significant procedural anxiety, a short-acting benzodiazepine such as alprazolam may be administered before surgery.

Postoperative pain control can be managed by alternating acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen. For patients who cannot take NSAIDs or those undergoing more invasive procedures, such as en bloc excisions, a short course (fewer than 7 days) of oral narcotic pain medication may be necessary to ensure adequate postoperative pain relief.

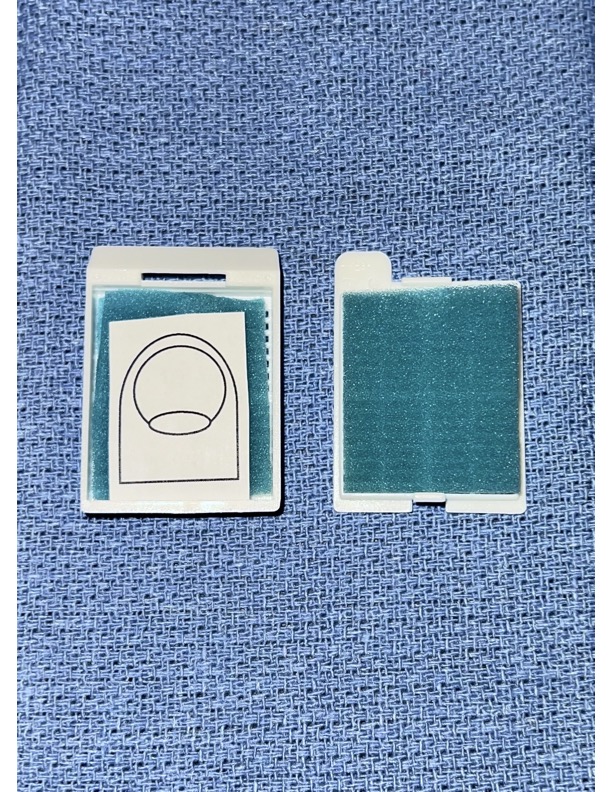

A critical step in successful nail surgery is the orientation and mapping of the biopsy or excision specimen. Similar to specimen management in Mohs surgery, accurate orientation is crucial for diagnostic purposes and ensures proper histological processing. Proper orientation and mapping keep the epithelium facing up and prevent curling or rolling of thin or long specimens. Effective orientation is achieved by inking the specimen and placing it in a nail cassette, which distinguishes it as special and assists the histology technician, who may be less familiar with nail specimens compared to standard skin specimens (see Image. Nail Surgery Specimen Map). The pathology requisition typically includes specific instructions for longitudinal sectioning of nail specimens.

Technique or Treatment

Nail Avulsions

Nail avulsions can be either complete or partial. Partial avulsions include techniques such as distal, proximal, lateral curl, and trap door methods. A review by Collins et al provides a detailed overview of these partial avulsion techniques. When possible, the avulsed nail plate should be replaced after the procedure to act as a biological dressing, which can also help reduce postoperative pain.[13] Partial nail plate avulsion is generally preferred over complete avulsion when feasible, as it tends to enhance patient comfort during recovery. However, exceptions exist, such as in cases of onychogryphosis, where the nail plate itself is the source of the issue, and complete avulsion may be therapeutic.

A trap door avulsion is performed distoproximally, beginning with a scalpel blade. The blade should be visible through the nail plate, which is then carefully elevated with upward pressure until the onychodermal band is released. The nail plate is most firmly attached distally at the onychodermal band, which allows for the transition to a periosteal elevator for blunt avulsion proximally. This technique is beneficial for erythronychia when an onychopapilloma is suspected, as it facilitates visualization of the transition from the matrix to the nail bed.

For partial proximal nail avulsion, the margins of the proximal nail fold around the region to be explored or biopsied should be marked with a surgical pen. Tangential incisions are made with a scalpel, and the proximal nail fold is carefully undermined using an elevator or iris scissors. Lateral adhesions are then released with a scalpel or scissors. Skin hooks or sutures are used to reflect the proximal nail fold, with assistance from at least 1 assistant. The English anvil nail splitter is then employed to cut the nail plate horizontally, distal to the lunula, approximately three-quarters of the way across. This allows the nail plate to be curled to the side, facilitating visualization and instrumentation of the nail matrix.

Suturing through the nail plate to secure it after the procedure can be challenging. The process can cause the needle tip to bend or break, and suturing from the plate to the soft tissue may lead to keratin granulomas. To avoid these complications, using an 11-blade scalpel to create a needle hole in the nail plate before suturing facilitates smoother suture passage. Rapidly absorbing sutures, such as polyglactin 910 (Vicryl Rapide™), which dissolve over 1 to 2 weeks, are preferred. Additionally, the "X" suture technique has been suggested as an effective hemostatic method in nail surgery, as it reduces the risk of tearing fragile structures.[14]

Longitudinal Melanonychia

Longitudinal melanonychia is a commonly encountered condition. Jellinek has proposed an algorithm for approaching this pathology.[15] If the lesion is located on the distal matrix and measures less than 3 mm, a 3-mm punch excision is recommended. For lesions on the distal matrix greater than 3 mm, a tangential matrix shave biopsy is the preferred method.

Regardless of size, lesions on the proximal matrix should also be managed with a tangential matrix shave biopsy. A tangential shave biopsy is generally effective across various nail regions and helps minimize the risk of postoperative nail dystrophy, which can result from damage during matrix biopsies. In cases with a high suspicion of invasive melanoma, an excisional full-thickness biopsy or multiple scouting biopsies of the affected nail unit should be performed.[15]

Concerns regarding transected or missed diagnoses with tangential matrix shave biopsies for longitudinal melanonychia have been addressed in recent studies. A study involving 22 cases of longitudinal melanonychia biopsied using the tangential technique reported a mean specimen thickness of 0.59 mm and a mean lesion depth of 0.08 mm, with no transections or missed diagnoses.[16] While longitudinal erythronychia is most commonly caused by benign neoplasms, nail surgery can also be used to rule out malignancy and alleviate symptoms.[17]

For a shave or tangential nail matrix biopsy, the lesion should be marked at the proximal nail fold and hyponychium before administering the anesthesia. A tourniquet must also be applied. A partial plate avulsion, preferably using a partial proximal or lateral curl technique, should be performed, followed by reflecting the proximal nail fold and scoring the margins of the biopsy specimen (1-2 mm). The blade is then turned, and the specimen is superficially removed with a 15-blade scalpel at a horizontal angle to the nail matrix. The excision should be thin enough that the scalpel blade is visible, and one could read a newspaper through it. Forceps should be used minimally to avoid crushing the tissue. The specimen should be inked and placed in a nail cassette for longitudinal sectioning. The nail plate and fold may then be repositioned to their normal anatomical positions and sutured in place.

Punch biopsies are commonly performed on the nail bed, nail plate, and distal matrix under sterile conditions, with anesthesia and a tourniquet in place. A 3-mm punch is typically sufficient for these procedures. The punch instrument should be positioned on the target area, scored, and then twisted until it reaches the bone. Scissors are used to snip the specimen's base perpendicularly, and forceps should be avoided to prevent tissue crush. Adjacent biopsies may be conducted for a more thorough tissue examination. The surgical site typically heals without causing permanent nail changes when performed on the nail plate or bed. However, onycholysis may occur if the procedure is performed too distally on the nail matrix.[18]

Lateral longitudinal excision is commonly used for the histologic diagnosis of lateral longitudinal melanonychia or erythronychia. Histological studies have shown that the matrix extends 75% of the distance from the cuticle to the distal interphalangeal crease. Therefore, it is essential to include the entire lateral horn of the matrix to prevent the growth of a nail spicule postoperatively.[19]

The technique involves scoring and incising the lateral nail fold, plate, and matrix or bed with a scalpel blade down to the bone in a fusiform shape, followed by excision with fine-tipped scissors to ensure the entire lateral matrix and horn are included. Due to anatomical considerations, this procedure is typically wider on the thumb and great toe. Following the excision, primary or partial repair may be performed, depending on the size of the excision and surrounding skin laxity. In cases with minimal surrounding laxity, secondary intention healing may be the most appropriate option.

En Bloc Excision

En bloc excision involves the excision of the entire nail unit, including the bed, matrix, plate, and nail folds. This technique may be necessary during Mohs surgery or digit-sparing excisions for conditions such as squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma in situ, and thin melanoma lesions of the nail unit. A retrospective cohort review of patients with nail apparatus melanoma indicated that excision followed by coverage with a full-thickness skin graft resulted in a 100% overall survival rate at 5 years, suggesting that total amputation may not be required in many cases.[20] This outcome should encourage dermatologic surgeons to be more confident in performing these procedures. When possible, digit-preserving surgery for nail unit malignancies is crucial in optimizing functional outcomes.

Postprocedural Care

The nail surgeon should oversee the application of the postoperative dressing. The tourniquet should be removed by the surgeon, with the timing documented. Reperfusion should be monitored and recorded. Hemostatic options before dressing application include kaolin-impregnated gauze, microporous polysaccharide hemospheres powder, and brimonidine 0.33% gel.[21][22][23] A pressure dressing is recommended, followed by the application of a liquid skin adhesive and stretchable paper tape (eg, Hypafix®), which is applied top to bottom and side to side.

The finger should never be taped circumferentially to prevent postoperative ischemia of the digit. The dressing technique should be documented, and patients should be observed in the office for approximately 20 minutes after dressing application to monitor for any bleeding. Patients should receive detailed postoperative wound care instructions and counseling. The original dressing should remain in place and kept dry for 24 to 48 hours. After this period, daily wound care should be performed by gently removing the dressing, washing the site with water and mild soap, applying petroleum ointment, and rewrapping the site with fresh nonstick gauze dressings.

An expert consensus published in 2021 provided guidance for selecting Current Procedural Terminology codes for nail procedures. The relative infrequency of nail procedures compared to other dermatologic surgeries was identified as a key factor contributing to billing confusion. The article outlined various nail procedures, highlighting that both nail plate avulsion and chemical matrixectomy (permanent removal of the nail matrix to prevent regrowth) are billed under code 11750, as an example.[24]

Complications

Pain and mild edema are common and expected adverse effects of nail surgery. To mitigate these issues, careful tissue handling, suturing without excess tension, limiting activity in the immediate postoperative period (typically for at least 48-72 hours), and elevating the affected limb are recommended.[25] Antibiotics are not routinely prescribed but may be considered for high-risk areas, such as the toe, in patients with an elevated risk of infection or poor blood supply to the extremities. This includes individuals with weakened immunity or diabetes.

Nail dystrophy is a potential complication of nail surgery, and understanding nail anatomy is crucial for its prevention. The risk of dystrophy depends on the nail region involved in the procedure—the nail bed epithelium has a low risk, the distal nail matrix a moderate risk, and the proximal nail matrix a high risk. This variation arises because the proximal matrix forms the dorsal nail plate surface, whereas the distal matrix contributes to its ventral "underside." Scarring in the proximal matrix is more likely to cause surface deformities of the nail plate. In contrast, the nail bed primarily serves as vascular support for the nail plate, and injuries to this area generally do not result in nail dystrophy.

Dorsal pterygium may develop following nail surgery, but preventive techniques have been described, including the recent use of a nasopharyngeal tube as a "faux nail."[26] Postoperative inclusion cysts, which can result from suturing and needle trauma, may be prevented by gentle tissue mobilization. Nail spicules may occur following lateral matrixectomy, lateral longitudinal excisions, or en bloc excisions of the nail unit when remnants of the lateral matrix horns are inadvertently left in place. To avoid this issue, curettage, excision, or chemical or electrical cauterization of the lateral matrix horn down to the bone is recommended during these procedures. Additional potential sequelae of nail surgery include longitudinal chromonychia, focal nail plate thinning, brittle nails, onycholysis, nail ridges, pyogenic granuloma, and persistent longitudinal nail fissures.[27][28]

The potential downsides of nail surgery include unnecessary imaging and overly aggressive procedures stemming from misconceptions that nail malignancies require more aggressive treatment than other cutaneous malignancies. Several focused reviews on the surgical management of nail unit skin cancers have highlighted misconceptions in nail malignancy management and provided treatment recommendations. Commonly debunked myths include the following:

- All nail unit resection modalities are equally effective.[29][30][31]

- Bony invasion by squamous cell carcinoma of the nail unit always necessitates amputation.[32][33]

- Nail unit squamous cell carcinoma uniformly warrants sentinel lymph node biopsy.[34][35][36]

Other sources have discredited additional misconceptions, including:

Clinical Significance

Nail surgery is a critical component of dermatological practice, providing diagnostic and therapeutic benefits for various conditions, including inflammatory disorders and benign and malignant neoplasms. A thorough understanding of nail anatomy and proficiency in various surgical techniques are essential for dermatologists and surgeons to effectively manage cases requiring biopsy, avulsion, excision, Mohs surgery, or other interventions. By implementing precise biopsy techniques and adhering to strict infection control measures, clinicians can safely obtain tissue samples to distinguish between benign causes of longitudinal melanonychia and melanoma, ensuring appropriate management. Continuing education and proficiency in nail surgery techniques are essential for clinicians to deliver optimal dermatologic care, ultimately improving patient outcomes and quality of life.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Nail surgery depends on a cohesive, interprofessional healthcare team to deliver patient-centered care, optimize outcomes, ensure safety, and enhance team performance. Dermatologists, surgeons, nurses, and support staff collaborate closely throughout the surgical process. Dermatologists and dermatopathologists are responsible for diagnosing nail disorders, while dermatologists, Mohs surgeons, and other physicians perform the surgeries. Nurses and medical assistants assist with procedures and provide essential postoperative patient education.

Ethical considerations, including informed consent and patient autonomy, guide all decisions to uphold patient-centered care standards. Informed consent is particularly important, as patients may experience permanent deformities following certain nail procedures. Ongoing education for the patient care team ensures they remain current with advancements in nail surgery techniques and patient care protocols. The interprofessional nail surgery team optimizes patient outcomes, enhances safety, and fosters positive patient care experiences through collaborative efforts and a commitment to patient-focused care.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of nail biopsies performed using the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database 2012 to 2017. Dermatologic therapy. 2021 May:34(3):e14928. doi: 10.1111/dth.14928. Epub 2021 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 33665923]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLencastre A, Arnal C, Richert B. Surgery for benign nail tumor. Hand surgery & rehabilitation. 2024 Apr:43S():101651. doi: 10.1016/j.hansur.2024.101651. Epub 2024 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 38296187]

Martin ET, Kaye KS, Knott C, Nguyen H, Santarossa M, Evans R, Bertran E, Jaber L. Diabetes and Risk of Surgical Site Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 2016 Jan:37(1):88-99. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.249. Epub 2015 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 26503187]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceToybenshlak M, Elishoov O, London E, Akopnick I, Leibner ED. Major complications of minor surgery: a report of two cases of critical ischaemia unmasked by treatment for ingrown nails. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 2005 Dec:87(12):1681-3 [PubMed PMID: 16326886]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBettin CC, Gower K, McCormick K, Wan JY, Ishikawa SN, Richardson DR, Murphy GA. Cigarette smoking increases complication rate in forefoot surgery. Foot & ankle international. 2015 May:36(5):488-93. doi: 10.1177/1071100714565785. Epub 2015 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 25583954]

Jiménez-Briones L, Medrano Martínez N, Córdoba García-Rayo M, Vírseda González D, Rodríguez-Lomba E. A new method to optimize tourniquet during first toenail surgery. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2024 Jul:91(1):e5-e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2024.01.074. Epub 2024 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 38360174]

Lahham S, Tu K, Ni M, Tran V, Lotfipour S, Anderson CL, Fox JC. Comparison of pressures applied by digital tourniquets in the emergency department. The western journal of emergency medicine. 2011 May:12(2):242-9 [PubMed PMID: 21691536]

Becerro de Bengoa Vallejo R, Losa Iglesias ME, Cervera LA, Fernández DS, Prieto JP. Efficacy of intraoperative surgical irrigation with polihexanide and nitrofurazone in reducing bacterial load after nail removal surgery. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2011 Feb:64(2):328-35. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.01.011. Epub 2010 Nov 26 [PubMed PMID: 21112671]

Vinycomb TI, Sahhar LJ. Comparison of local anesthetics for digital nerve blocks: a systematic review. The Journal of hand surgery. 2014 Apr:39(4):744-751.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.01.017. Epub 2014 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 24612831]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceThomson CJ, Lalonde DH, Denkler KA, Feicht AJ. A critical look at the evidence for and against elective epinephrine use in the finger. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2007 Jan:119(1):260-266. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000237039.71227.11. Epub [PubMed PMID: 17255681]

Nayaz M, Mohamed A, Nawaz A. Accidental Digital Ischemia by an Epinephrine Autoinjector. Cureus. 2023 Mar:15(3):e36429. doi: 10.7759/cureus.36429. Epub 2023 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 37090392]

Krunic AL, Wang LC, Soltani K, Weitzul S, Taylor RS. Digital anesthesia with epinephrine: an old myth revisited. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2004 Nov:51(5):755-9 [PubMed PMID: 15523354]

Collins SC, Cordova K, Jellinek NJ. Alternatives to complete nail plate avulsion. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2008 Oct:59(4):619-26. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.05.039. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18793936]

Dorado Caycedo I, Dehavay F, Richert B. The "X" Suture: A Versatile Technique for Nail Apparatus Surgery. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2022 Dec 1:48(12):1362-1364. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000003643. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36449882]

Jellinek N. Nail matrix biopsy of longitudinal melanonychia: diagnostic algorithm including the matrix shave biopsy. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2007 May:56(5):803-10 [PubMed PMID: 17437887]

Di Chiacchio N, Loureiro WR, Michalany NS, Kezam Gabriel FV. Tangential Biopsy Thickness versus Lesion Depth in Longitudinal Melanonychia: A Pilot Study. Dermatology research and practice. 2012:2012():353864. doi: 10.1155/2012/353864. Epub 2012 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 22496683]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCurtis KL, Ho B, Jellinek NJ, Rubin AI, Tosti A, Lipner SR. Diagnosis and management of longitudinal erythronychia: A clinical review by an expert panel. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2024 Sep:91(3):480-489. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2024.04.032. Epub 2024 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 38705197]

Jellinek NJ. Nail surgery: practical tips and treatment options. Dermatologic therapy. 2007 Jan-Feb:20(1):68-74 [PubMed PMID: 17403262]

Reardon CM, McArthur PA, Survana SK, Brotherston TM. The surface anatomy of the germinal matrix of the nail bed in the finger. Journal of hand surgery (Edinburgh, Scotland). 1999 Oct:24(5):531-3 [PubMed PMID: 10597925]

Seyed Jafari SM, Lieberherr S, Cazzaniga S, Beltraminelli H, Haneke E, Hunger RE. Melanoma of the Nail Apparatus: An Analysis of Patients' Survival and Associated Factors. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland). 2022:238(1):156-160. doi: 10.1159/000514493. Epub 2021 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 33789262]

Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Kaolin-impregnated gauze for hemostasis following nail surgery. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2021 Jul:85(1):e13-e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.008. Epub 2020 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 32059991]

Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Microporous polysaccharide hemospheres powder for hemostasis following nail surgery. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2023 Jul:89(1):e33-e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.069. Epub 2021 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 33775719]

Lipner SR. Novel Use of Brimonidine 0.33% Gel for Hemostasis in Nail Surgery. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2019 Jul:45(7):993-996. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001632. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30148732]

Baltz JO, Rubin A, Adigun C, Daniel CR 3rd, Hinshaw M, Knacksedt T, Lipner SR, Rich P, Stern D, Zaiac M, Jellinek NJ. Expert Consensus on Nail Procedures and Selection of CPT Codes. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2021 Aug 1:47(8):1079-1082. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000003081. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34397542]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZamour S, Dumontier C. Complications in nail surgery and how to avoid them. Hand surgery & rehabilitation. 2024 Apr:43S():101648. doi: 10.1016/j.hansur.2024.101648. Epub 2024 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 38244695]

Jellinek NJ, Cressey BD. Nail Splint to Prevent Pterygium After Nail Surgery. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2019 Dec:45(12):1733-1735. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001754. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30624256]

Moossavi M, Scher RK. Complications of nail surgery: a review of the literature. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2001 Mar:27(3):225-8 [PubMed PMID: 11277886]

Lee DH, Mignemi ME, Crosby SN. Fingertip injuries: an update on management. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2013 Dec:21(12):756-66. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-21-12-756. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24292932]

Gou D, Nijhawan RI, Srivastava D. Mohs Micrographic Surgery as the Standard of Care for Nail Unit Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2020 Jun:46(6):725-732. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000002144. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31567588]

Dika E, Fanti PA, Patrizi A, Misciali C, Vaccari S, Piraccini BM. Mohs Surgery for Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Nail Unit: 10 Years of Experience. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2015 Sep:41(9):1015-9. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000452. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26241670]

Tang N, Maloney ME, Clark AH, Jellinek NJ. A Retrospective Study of Nail Squamous Cell Carcinoma at 2 Institutions. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2016 Jan:42 Suppl 1():S8-S17. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000521. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26730977]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDika E, Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Vaccari S, Misciali C, Patrizi A, Fanti PA. Mohs surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the nail: report of 15 cases. Our experience and a long-term follow-up. The British journal of dermatology. 2012 Dec:167(6):1310-4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11129.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22762413]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceClark MA, Filitis D, Samie FH, Piliang M, Knackstedt TJ. Evaluating the Utility of Routine Imaging in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Nail Unit. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2020 Nov:46(11):1375-1381. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000002352. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32106119]

Kofler L, Kofler K, Schulz C, Breuninger H, Häfner HM. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for high-thickness cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Archives of dermatological research. 2021 Mar:313(2):119-126. doi: 10.1007/s00403-020-02082-1. Epub 2020 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 32385689]

Jansen P, Petri M, Merz SF, Brinker TJ, Schadendorf D, Stang A, Stoffels I, Klode J. The prognostic value of sentinel lymph nodes on distant metastasis-free survival in patients with high-risk squamous cell carcinoma. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2019 Apr:111():107-115. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.02.004. Epub 2019 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 30849684]

Quinn PL, Oliver JB, Mahmoud OM, Chokshi RJ. Cost-Effectiveness of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy for Head and Neck Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. The Journal of surgical research. 2019 Sep:241():15-23. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2019.03.040. Epub 2019 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 31004868]

Rayatt SS, Dancey AL, Davison PM. Thumb subungual melanoma: is amputation necessary? Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2007:60(6):635-8 [PubMed PMID: 17485051]

Park KG, Blessing K, Kernohan NM. Surgical aspects of subungual malignant melanomas. The Scottish Melanoma Group. Annals of surgery. 1992 Dec:216(6):692-5 [PubMed PMID: 1466623]

Swanson AB, Hagert CG, Swanson GD. Evaluation of impairment of hand function. The Journal of hand surgery. 1983 Sep:8(5 Pt 2):709-22 [PubMed PMID: 6630952]

Hochwalt PC, Christensen KN, Cantwell SR, Hocker TL, Brewer JD, Baum CL, Arpey CJ, Otley CC, Roenigk RK. Comparison of full-thickness skin grafts versus second-intention healing for Mohs defects of the helix. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2015 Jan:41(1):69-77. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000208. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25545178]