Introduction

Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) was initially discovered in blood lymphocytes of adults with lymphoproliferative diseases or AIDS and was labeled human B-lymphotropic virus. Further research identified HHV-6 in CD4+ lymphocytes and as a member of the herpesviruses. As it was the sixth herpesvirus isolated, it was then subsequently renamed human herpesvirus 6. Typical of a herpes virus, HHV-6 has been known to establish acute, incessant and permanent infection.

HHV-6 is the collective name for the double-stranded DNA viruses HHV-6A and HHV-6B. HHV-6A and HHV-6B, are officially recognized as distinct viruses instead of variants within the herpesvirus family. While much less is known about HHV-6A, it occurs more frequently in the immunocompromised host. In contrast, research has identified HHV-6B as the etiologic agent of the childhood illness exanthema subitem (roseola infantum).[1] The acquisition of HHV-6B is quite common in the young and is frequently seen throughout emergency departments worldwide. HHV-6B is a ubiquitous virus, with over 90% of the human population infected within the first 3 years of life.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

HHV-6A, HHV-6B, and HHV-7 all share some level of homology with human cytomegalovirus (CMV), the only other human beta-herpesvirus.[1] Both HHV-6A and HHV-6B replicate in T-cells. However, they differ in the receptors used for cellular entry. Contrary to the human cluster differentiation 46 (CD46) used by the HHV-6A virus, studies show cluster differentiation 134 (CD134) is the primary receptor for HHV-6B.[2] CD134 only expresses on activated T cells.[3] Similar to HHV-8 also known as the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) and the Epstein Barr Virus (EBV), studies of HHV-6 prove the virus to be oncogenic and destructive to autoimmune cells. Once bound to its respective receptor, HHV-6 establishes latency in lymphocytes and possesses a robust immunomodulatory capacity that can trigger both immunosuppressive and chronic inflammatory pathways.[3]

By adulthood, more than 95% of the population is seropositive for HHV-6A, HHV-6B, or both variants. Present serologic methods are ineffective in isolating one variant from the other.[4] It is now well known that HHV-6 is the primary cause of roseola infantum in childhood. HHV-6B primarily infects infants and is the leading cause of virus reactivation in both, immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts.[1] In the general population, the vast majority of adults with chronic HHV-6 remain asymptomatic. Research of HHV-6 and its role in the central nervous system is ongoing. In one study, more than 70% of children with primary HHV-6 infection had the virus DNA in their CSF. These children had neurologic sequelae concurrently with primary HHV-6 infection, including frequent febrile seizures.[5] Contrarily, other researchers identified only a 0% to 4% prevalence of HHV-6 DNA in the CSF of children with febrile seizures and AIDS patients with neurological symptoms.[5] These viruses have been linked to illnesses in immunocompromised patients and may play a role in the etiology of Hodgkin's disease and other malignancies.[4] Additionally, successful investigations have identified HHV-6A and HHV-6B as the source of opportunistic infections in immunocompromised patients including those with encephalitis, hepatitis, colitis, and pneumonitis.[6]

Epidemiology

Researchers have identified HHV-6B as the etiologic pathogen responsible for most HHV-6 infections presenting with symptoms. While research supports that a majority of people have been infected with HHV-6 at some point in their life, primary infection with HHV-6 occurs within the first 2 years. In this age group, it is usually associated with an undifferentiated febrile illness, albeit a subset of children will exhibit the classic manifestations of roseola infantum.[1] Several investigative reports have recorded a decline in seropositivity with an increase in age.[4]. Although primary HHV-6 infection is uncommon in adults, reactivation can occur at any age. HHV-6 infection has no sexual proclivity and may occur in people of all races.

HHV-6 is a ubiquitous virus found worldwide. In a large prospective study of North American children, the peak age of HHV-6 acquisition was between 6 and 9 months of age.[1] Similar to the United States, in the UK and Japan, 97 to 100 % of primary infections result from HHV-6B. While epidemiology reports of HHV-6A are limited, research suggests that HHV-6A infection is acquired later in life and that primary infection with this particular variant often occurs without symptoms.[7] However, several groups have recorded HHV-6A in symptomatic children from Africa and the USA. Furthermore, HHV-6A was identified as the predominant form of the virus isolated in HIV positive infants in an endemic region of sub-Saharan Africa.[7] Among different populations, seroprevalence varies drastically. There is a documented rate of 20% seroprevalence in pregnant Moroccan women and 100% in asymptomatic Chinese adults. Seroprevalence ranged roughly from 39 to 80% among ethnically diverse adult populations from Tanzania, Malaysia, Thailand, and Brazil.[4]

Pathophysiology

Overall, primary HHV-6 infection is among the most prevalent causes of acute febrile illness in young children. It is also a significant cause of visits to the emergency department, hospitalizations, and febrile seizures.[1] HHV-6 belongs to the Betaherpesvirinae subfamily and the Roseolovirus genus. The virion particle has the characteristic structure of a herpesvirus, with a central core containing the viral DNA, a capsid, and a protein-rich tegument layer that is surrounded by a membrane.

The principal target cell for HHV-6 is the mature CD4+ T cell.[1] The virus has demonstrated pleiotropic effects on the immune system including modulating natural killer cell function. In vivo, HHV-6 primarily infects and replicates in CD4 lymphocytes after attachment to the CD46 cellular receptor. Via receptor-mediated endocytosis, HHV-6 gains entry into cells with subsequent viral replication (Ablashi). After primary infection, the virus DNA lives in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC).[1]

While the exact mechanism of HHV-6 transmission is still under investigation, several studies have elucidated the viral transmission via saliva. It appears that transfer via saliva from mother to infant is the most common route. Several early reports described infectious HHV-6 as being present in saliva from nearly every person tested.[4] Additionally, salivary samples from 90% of persons examined contained HHV-6 DNA, while in another PCR-based study only 3% of persons were positive, although 63% of salivary gland biopsy specimens were positive.[4] The HHV-6 genome has also appeared in the CSF of children during primary and latent infections as well as in the brain matter of normal adults on autopsy, suggesting both the CNS and salivary glands as a reservoir for viral latency and persistent infection.[1][4]

History and Physical

Though the various clinical features and diseases associated with HHV-6 are still under investigation, research already well documents that HHV-6 plays an extensive role in central nervous system diseases and immunocompromised individuals including transplant recipients.[8] Infection with HHV-6 is usually benign and self-limiting. Symptomatic individuals are generally infants or those immunocompromised adults who are experiencing reactivation of the disease.

HHV-6B is the causative agent in exanthema subitum (also known as roseola infantum), a childhood disease characterized by high fever and a mild skin rash, and accounts for up to 10 to 17% of acute febrile Emergency department visits in children up to 36 months of age.[9] Primary HHV-6 infection accounts for over 36% of all cases of acute fever in children between 12 and 15 months old and is almost exclusively caused by HHV-6B, not HHV-6A.[9][8][10]

The diagnosis of roseola infantum is clinical. It is often precipitated by abrupt onset of high fever with temperatures reaching 40°C (104 F) for three to five days. During the initial febrile phase, some children will have periorbital edema, conjunctivitis or inflammation of the tympanic membranes while many others will be active and well.[9] Other symptoms in children include lymphadenopathy, gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, including liver dysfunction and hepatitis, and bulging fontanelles.[11] In adults, hepatitis and symptoms consistent with encephalitis are common.[9] In transplant recipients, symptoms often include fever, graft versus host disease (GVHD), symptoms of graft rejection, interstitial pneumonitis, myelitis, and rash.[12]

Physical examination findings are usually consistent with the symptoms previously described. In children, with defervescence of the fever, there is often an eruption of a blanching maculopapular rash that is rose-pink and approximately 2 to 5mm with a surrounding halo. The rash typically persists for one to two days and often spreads centrifugally. However, there are documented cases of fever without a rash.[13] Inflamed tympanic membranes and signs of upper or lower respiratory tract infections are common in children, while adults may have a fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy on physical exams.[12]

Evaluation

Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) can be diagnosed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), serology or viral cultures, with PCR being the predominant method used.[12] However, laboratory testing is unlikely to be obtained in immunocompetent individuals due to the self-limiting nature of the disease. Saliva is the primary reservoir for virus transmission, as it frequently isolated in salivary glands. While there have been no reports of virus transmission via blood transfusion and breastfeeding there has been documentation of HHV-6 after organ transplantation.[12] Most researchers strongly believe that infection with HHV-6B occurs early in life, while infection with HHV-6A develops later. Both variants of the virus have been simultaneously detected in adults suggesting the viruses chronically infect many people.

Laboratory studies in HHV-6 may show leukocytosis, leukopenia, and anemia.[13] In renal transplant patients and those with liver dysfunction, renal studies, and hepatic studies should be obtained respectively, to rule out electrolyte disturbance and hepatitis.

Indication for radiological imagining is dependent on the clinical presentation, especially in immunocompromised individuals. Chest radiography can be obtained to rule out other etiologies in adults including pneumonia and pneumonitis. The need for imaging is less frequently the case in children. Computed tomography (CT) of the head with and or without contrast can be obtained to search for other treatable diseases. In cases where the central nervous system is afflicted, a lumbar puncture can be performed. HHV-6 infection of the CNS often has a mild pleocytosis with elevated protein. CSF can be sent for HHV-6 PCR studies to confirm the diagnosis.[14]

Treatment / Management

Currently, there is no approved compound exclusively for the treatment of HHV-6, and there is no vaccine available.[8] It is generally not recommended to provide antiviral prophylaxis for HHV-6 infection. Instead, it is advised to implement early antiviral treatment, especially in cases of HHV-6 encephalitis. First-line therapy with intravenous ganciclovir and foscarnet are recommended, with treatment for 3 to 4 weeks.[15] In patients undergoing stem-cell transplantation, treatment with ganciclovir has documented benefits and is the suggested antiviral of choice.[15](B3)

HHV-6 infections in immunocompetent children are self-limiting and do not require treatment. Treatment of infants with roseola infantum is usually supportive.[12] Antipyretics like acetaminophen or ibuprofen are recommended therapy for high-grade fever and those at risk for febrile seizures. If a febrile seizure occurs, anti-epileptics are unnecessary. Individuals who present HHV-6 infection manifested by CNS involvement, including febrile seizures, should be admitted to the hospital.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes:

- Infectious mononucleosis

- Cytomegalovirus infection

- Viral hepatitis

- Herpes simplex virus infection

- meningitis

- Rubella

- Viral pneumonia

- Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome)

In children with classic roseola infantum, HHV-6 is the etiologic pathogen. However, several other diseases can cause fever and rash. More severe, less benign, causes of such symptoms requires exclusion. In immunocompetent adults, infection with HHV-6 manifests similarly to mononucleosis. Thus EBV and CMV should be excluded. Immunocompromised patients, especially those receiving organ transplants and those with AIDS are generally symptomatic. This cohort of individuals with HHV-6 disease are often concomitantly infected with CMV, and antiviral treatment should commence promptly. HHV-6 correlates with several other diseases including hepatitis, herpes simplex, meningitis, rubella, viral pneumonia, and DRESS syndrome.[16] Additionally, documentation exists of HHV-6 in cases of multiple sclerosis encephalitis and interstitial pneumonitis.[17] It is worth noting that only HHV-6A has associations with Hashimoto thyroiditis.[12]

Prognosis

Generally, primary infection with HHV-6 is self-limiting, and those who are immunocompetent survive without sequelae. In immunosuppressed individuals, reports have described more severe illness. Documentation exists of pneumonitis, hepatitis, and organ rejection in transplant patients, with death reported in patients with encephalitis and meningoencephalitis.[18] Similarly, in Japan a 2003 to 2004 survey of patients with exanthema subitum-associated encephalitis had an unusually poor prognosis,[19] with reported fatalities in two children with encephalopathy secondary to HHV-6 infection. The children were discovered to have a genetic mitochondrial disorder.[20]

Complications

Universally, HHV-6 primary infection is benign with spontaneous resolution in 5 to 7 days. The most common complication of roseola infantum is febrile seizures. Additional complications are often due to HHV-6 neurotrophic effects, as highlighted in cases where the central nervous system becomes compromised, for example, in cases of meningoencephalitis and encephalopathy. In these cases, the virus occupies the brain during primary infection and can remain dormant in brain tissue.[21] Subsequently, there are records of cases of acute or subacute encephalitis sometimes associated with diffuse or multifocal demyelination.[4] HHV-6 infrequently causes opportunistic infection in immunocompromised individuals. HHV-6A and HHV-6B activity have been detected following renal, liver transplants and bone marrow transplants (BMT).[4]

Deterrence and Patient Education

In an otherwise healthy infant with roseola infantum, parent education is crucial in alleviating anxiety about fever and the possible febrile seizure. The importance of supportive care with antipyretics and the futility of antibiotics requires explanation. In immunocompromised individuals, the complex symptoms and other secondary viral illnesses that may accompany HHV-6 infection are counseling points with emphasis on seeking early medical attention when symptoms arise.

Pearls and Other Issues

It is generally accepted that HHV-6B is the causal variant responsible for most primary infections while HHV-6A is acquired after HHV-6B, through asymptomatic infection.[22]1. Distinguishing cases of primary HHV-6 infection with the typical roseola infantum rash from other illnesses is key to eliminating more severe diagnoses. The most common complication of HHV-6 infection is roseola infantum, and HHV-6 accounts for approximately 10 to 20% of febrile illnesses in children 6 months to 3 years of age. Febrile seizures, gastrointestinal and respiratory tract symptoms are less common and are usually self-limiting. Supportive care with rest and hydration is the accepted approach for treatment in this subgroup. Similar to other herpes viruses, HHV-6 replicates in the salivary glands and is latent in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Diagnosis of HHV-6 via laboratory studies in the immunocompetent host is usually unnecessary. However, PCR, serologic studies or viral culture are often necessary for immunocompromised individuals suspected of harboring HHV-6.

HHV-6 infection correlates with more severe diseases including mononucleosis, colitis, myocarditis, and hepatitis, in addition to the documented central nervous system complications of encephalitis and meningoencephalitis. Early recognition and treatment of neurological complications are integral in preventing adverse outcomes. Children and adults that have cancer, who are recipients of allogeneic transplants and those with immunosuppression disorders are at risk for reactivation of HHV-6. In such cases, individuals may present with a fever, rash, and a decrease in circulating granulocytes and erythroid cells.[12] Though there are no approved therapies solely for HHV-6 infection, antiviral treatment with ganciclovir and/or foscarnet have proven successful in treating the neurological sequelae previously described.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

HHV-6 commonly presents with a rash in children presenting to the emergency room and pediatricians alike. While defining rashes can be challenging, isolating specific cofounding symptoms is imperative to differentiate between more toxic versus benign illnesses. The majority of HHV-6 infections are asymptomatic, transient, and do not require antiviral treatment. [Level II] Pediatric consultation is the recommendation for infants with roseola infantum who have febrile seizures. There are known complications from HHV-6, and those individuals with more ominous signs and symptoms including changes in mental status and organ failure would benefit from an interprofessional approach. In such cases insight from neurology and infectious disease physicians are imperative. When HHV-6 associated heart failure is suspected, early cardiology consultation is critical in managing infectious myocarditis in immunocompetent adult patients.[23] [Level IV]

Coordinated care from skilled nurses is prudent to monitor for deterioration and changes in vital signs. Similarly, laboratory assistance in expediting the preferred methods of viral detection in blood or CSF by PCR, or viral antigen in tissue by immunohistochemistry should not be discounted. (Level II) Lastly, the pharmacist is integral in providing ganciclovir and foscarnet anti-viral treatment in HHV-6 associated encephalitis.[24] [Level III] Together, a patient-centered, interprofessional team approach among clinicians, including physicians, laboratory, specialty-trained nursing, and pharmacy, communicating openly as a health care team, is recommended to improve outcomes in complex cases and provide the best patient outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

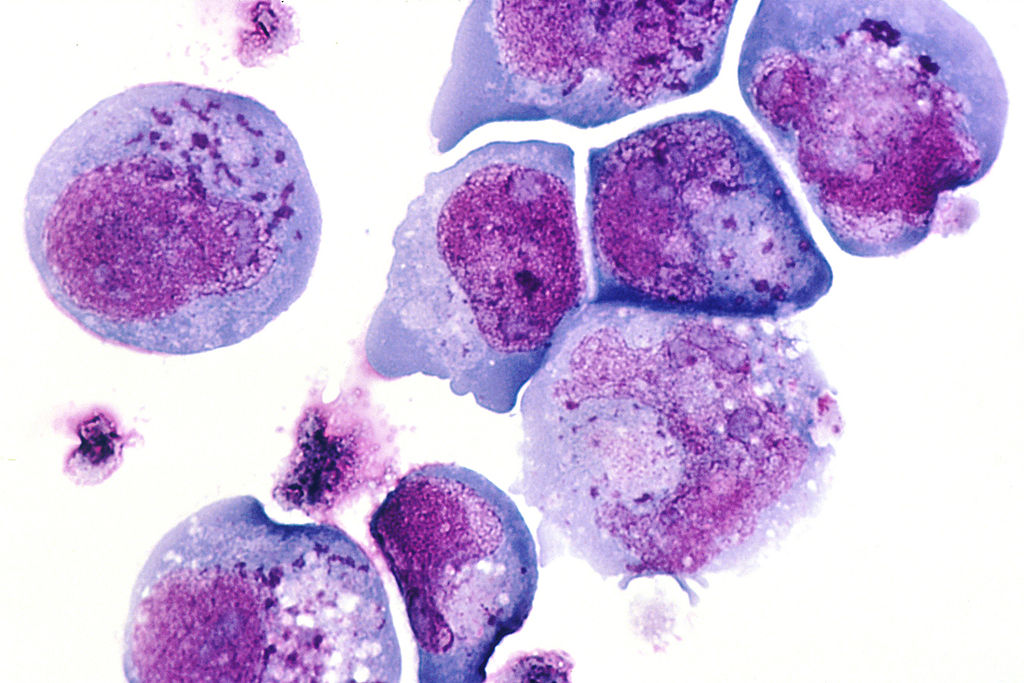

Human Herpes Virus 6 Cellular Infection. This histological slide shows cells infected with human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6), previously known as human B-lymphotropic virus (HBLV), a herpesvirus identified in October 1986. The photomicrograph highlights infected cells with inclusion bodies present in both the nucleus and cytoplasm. The slide is stained with hematoxylin and eosin. This virus is the causative agent of roseola infantum.

Contributed by Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

References

Caserta MT, Mock DJ, Dewhurst S. Human herpesvirus 6. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2001 Sep 15:33(6):829-33 [PubMed PMID: 11512088]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePantry SN, Medveczky PG. Latency, Integration, and Reactivation of Human Herpesvirus-6. Viruses. 2017 Jul 24:9(7):. doi: 10.3390/v9070194. Epub 2017 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 28737715]

Eliassen E, Lum E, Pritchett J, Ongradi J, Krueger G, Crawford JR, Phan TL, Ablashi D, Hudnall SD. Human Herpesvirus 6 and Malignancy: A Review. Frontiers in oncology. 2018:8():512. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00512. Epub 2018 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 30542640]

Braun DK,Dominguez G,Pellett PE, Human herpesvirus 6. Clinical microbiology reviews. 1997 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 9227865]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAnsari A, Li S, Abzug MJ, Weinberg A. Human herpesviruses 6 and 7 and central nervous system infection in children. Emerging infectious diseases. 2004 Aug:10(8):1450-4 [PubMed PMID: 15496247]

Agut H, Bonnafous P, Gautheret-Dejean A. Update on infections with human herpesviruses 6A, 6B, and 7. Medecine et maladies infectieuses. 2017 Mar:47(2):83-91. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2016.09.004. Epub 2016 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 27773488]

Ablashi D, Agut H, Alvarez-Lafuente R, Clark DA, Dewhurst S, DiLuca D, Flamand L, Frenkel N, Gallo R, Gompels UA, Höllsberg P, Jacobson S, Luppi M, Lusso P, Malnati M, Medveczky P, Mori Y, Pellett PE, Pritchett JC, Yamanishi K, Yoshikawa T. Classification of HHV-6A and HHV-6B as distinct viruses. Archives of virology. 2014 May:159(5):863-70. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1902-5. Epub 2013 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 24193951]

De Bolle L, Naesens L, De Clercq E. Update on human herpesvirus 6 biology, clinical features, and therapy. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2005 Jan:18(1):217-45 [PubMed PMID: 15653828]

Tesini BL, Epstein LG, Caserta MT. Clinical impact of primary infection with roseoloviruses. Current opinion in virology. 2014 Dec:9():91-6. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.09.013. Epub 2014 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 25462439]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHall CB, Long CE, Schnabel KC, Caserta MT, McIntyre KM, Costanzo MA, Knott A, Dewhurst S, Insel RA, Epstein LG. Human herpesvirus-6 infection in children. A prospective study of complications and reactivation. The New England journal of medicine. 1994 Aug 18:331(7):432-8 [PubMed PMID: 8035839]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCristoforo T, Le NK, Rye-Buckingham S, Hudson WB, Carroll LF. The Not-So-Soft Spot: Pathophysiology of the Bulging Fontanelle in Association With Roseola. Pediatric emergency care. 2020 Oct:36(10):e576-e578. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001447. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29489601]

Agut H, Bonnafous P, Gautheret-Dejean A. Laboratory and clinical aspects of human herpesvirus 6 infections. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2015 Apr:28(2):313-35. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00122-14. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25762531]

Arnež M, Avšič-Županc T, Uršič T, Petrovec M. Human Herpesvirus 6 Infection Presenting as an Acute Febrile Illness Associated with Thrombocytopenia and Leukopenia. Case reports in pediatrics. 2016:2016():2483183 [PubMed PMID: 27980872]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYavarian J, Gavvami N, Mamishi S. Detection of human herpesvirus 6 in cerebrospinal fluid of children with possible encephalitis. Jundishapur journal of microbiology. 2014 Sep:7(9):e11821. doi: 10.5812/jjm.11821. Epub 2013 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 25485059]

Prichard MN, Whitley RJ. The development of new therapies for human herpesvirus 6. Current opinion in virology. 2014 Dec:9():148-53. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.09.019. Epub 2014 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 25462447]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShiohara T, Iijima M, Ikezawa Z, Hashimoto K. The diagnosis of a DRESS syndrome has been sufficiently established on the basis of typical clinical features and viral reactivations. The British journal of dermatology. 2007 May:156(5):1083-4 [PubMed PMID: 17381452]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMarks GL, Nolan PE, Erlich KS, Ellis MN. Mucocutaneous dissemination of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus in a patient with AIDS. Reviews of infectious diseases. 1989 May-Jun:11(3):474-6 [PubMed PMID: 2546244]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBeović B, Pecaric-Meglic N, Marin J, Bedernjak J, Muzlovic I, Cizman M. Fatal human herpesvirus 6-associated multifocal meningoencephalitis in an adult female patient. Scandinavian journal of infectious diseases. 2001:33(12):942-4 [PubMed PMID: 11868775]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYoshikawa T, Ohashi M, Miyake F, Fujita A, Usui C, Sugata K, Suga S, Hashimoto S, Asano Y. Exanthem subitum-associated encephalitis: nationwide survey in Japan. Pediatric neurology. 2009 Nov:41(5):353-8. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.05.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19818937]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAl-Zubeidi D, Thangarajh M, Pathak S, Cai C, Schlaggar BL, Storch GA, Grange DK, Watson ME Jr. Fatal human herpesvirus 6-associated encephalitis in two boys with underlying POLG mitochondrial disorders. Pediatric neurology. 2014 Sep:51(3):448-52. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.04.006. Epub 2014 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 25160553]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMason EE, Printen KJ. Metabolic considerations in reconstitution of the small intestine after jejunoileal bypass. Surgery, gynecology & obstetrics. 1976 Feb:142(2):177-83 [PubMed PMID: 813311]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencede Andrade RP. A multicenter clinical evaluation of a new monophasic combination: Minulet (gestodene and ethinyl estradiol). International journal of fertility. 1989 Sep:34 Suppl():22-30 [PubMed PMID: 2576253]

Ashrafpoor G, Andréoletti L, Bruneval P, Macron L, Azarine A, Lepillier A, Danchin N, Mousseaux E, Redheuil A. Fulminant human herpesvirus 6 myocarditis in an immunocompetent adult: role of cardiac magnetic resonance in a multidisciplinary approach. Circulation. 2013 Dec 3:128(23):e445-7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001801. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24297820]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLe J, Gantt S, AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Human herpesvirus 6, 7 and 8 in solid organ transplantation. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2013 Mar:13 Suppl 4():128-37. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12106. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23465006]

Abdelrahim NA, Mohamed N, Evander M, Ahlm C, Fadl-Elmula IM. Human herpes virus type-6 is associated with central nervous system infections in children in Sudan. African journal of laboratory medicine. 2022:11(1):1718. doi: 10.4102/ajlm.v11i1.1718. Epub 2022 Sep 22 [PubMed PMID: 36263389]

Sumala S,Ekalaksananan T,Pientong C,Buddhisa S,Passorn S,Duangjit S,Janyakhantikul S,Suktus A,Bumrungthai S, The Association of HHV-6 and the TNF-α (-308G/A) Promotor with Major Depressive Disorder Patients and Healthy Controls in Thailand. Viruses. 2023 Sep 8; [PubMed PMID: 37766304]

Darvish Molla Z, Kalbasi S, Kalantari S, Bidari Zerehpoosh F, Shayestehpour M, Yazdani S. Evaluation of the association between human herpes virus 6 (HHV-6) and Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Iranian journal of microbiology. 2022 Aug:14(4):563-567. doi: 10.18502/ijm.v14i4.10243. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36721502]