Introduction

Emergent thoracotomy is a procedure that is intended to temporize wounds and stabilize a patient via direct control of intrathoracic injuries, decompression of pericardial tamponade, and control of the aorta to prevent exsanguination. There are particular situations when an emergent thoracotomy is indicated. However, in those instances, this procedure could very well be life-saving, allowing the patient to survive to definitive interventions. We will review the procedure below, as well as the criteria for when you should and should not consider performing a thoracotomy emergently. The primary goals of emergency room thoracotomy are following:[1]

- Hemorrhage control

- Release of cardiac tamponade[2][3]

- For open cardiac massage[4][5]

- Prevention of air embolism

- Exposure of descending thoracic aorta for cross-clamping

- Repair cardiac or pulmonary injury

Emergent thoracotomy is typically performed in an emergency room or operating room. The emergency provider needs to inform the surgeon and facilitate the procedure and also manage the patient after thoracotomy.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The thorax is located between the neck superiorly and the diaphragm inferiorly. Organs include lungs, heart, and major vascular structures, such as the ascending aorta, arch vessels, and descending aorta. The heart is usually located just off the midline to the left. The aortic root is at the midline, the aortic arch moves posterolateral to the left, and the descending aorta is adjacent to the spine. The great vessels and the aortic arch are posterior to the manubrium. The great vessels include the brachiocephalic, which diverges into the right common carotid and the right subclavian, left subclavian, and left common carotid arteries.

The pericardial sac surrounds the heart. The left phrenic nerve runs intimately with the lateral pericardial sac and is vulnerable to injury during thoracotomy. The left vagus nerve runs anterior to the aortic arch near the left subclavian artery, where it gives rise to the recurrent laryngeal nerve before traveling posteriorly to the root of the left lung and running adjacent to the esophagus, into the posterior mediastinum. The vagus nerve's anatomical location makes it much less susceptible to injury during resuscitative thoracotomy due to its location. The esophagus runs anterior to the spinal column and medial to the aorta. The thoracic duct runs anterolaterally to the spine and is challenging to visualize.

Indications

Indications for emergency room thoracotomy include:

- Patients who suffer penetrating cardiac trauma, who have cardiac tamponade identified on the FAST exam, or individuals who are pulseless and received CPR less than 15 minutes after traumatic thoracic injury.[6] The procedure itself is associated with a high mortality rate. The mortality rate associated with the emergency room thoracotomy is likely due to the critical condition of patients on whom it is performed, and there has been next to no success when emergent thoracotomy is performed beyond these indications.[7]

- Cardiac tamponade in the setting of penetrating cardiac trauma is a life-threatening condition and can quickly lead to death in patients. A pericardiocentesis may be an effective temporizing measure in patients with cardiac tamponade and hemodynamic instability with continued signs of life. A pericardiocentesis can be performed in either the prehospital setting with EMS or in the emergency room to attempt to stabilize a patient. Still, if they proceed to lose signs of life, an emergency room thoracotomy may be required until definitive treatment can be arranged.

- Blunt thoracic injury without other mortal injuries (such as massive cranial deformity), who lose vital signs but still preserve signs of life.[8] An example of this blunt trauma mechanism would include injuries sustained from motor vehicle accidents with steering wheel trauma to the chest.[9] The emergency room thoracotomy may be able to buy time until transport to an operating theater can be arranged. In the right patient population, this can not only save a life but can potentially lead to good recovery and function following otherwise fatal injuries.[10]

Contraindications

Emergency room thoracotomy should not be performed:

- On any patient who continues to have vital signs, including detectable but hypotensive blood pressure.

- If the circumstances appear futile, futile situations include no signs of life on scene of injury; asystole as presenting rhythm with no pericardial tamponade; pulseless for greater than 15 minutes; massive, nonsurvivable injuries.

- In the pediatric population, evidence suggests that in patients between ages 0-14 who suffered a blunt thoracic injury and met the remaining criteria (such as witness loss of pulse, no massive unsurvivable injury), withholding emergent thoracotomy should be considered due to the abysmally poor results. Pediatric patients ages 15-18 who suffered a blunt thoracic injury, as well as pediatric patients with penetrating thoracic injuries, would not be considered a relative contraindication.[11]

- There is also evidence that in an aging population, the procedure becomes increasingly futile, and withholding the procedure should be considered in any patient older than 57 years old.[12]

- Additionally, a thoracotomy should not be performed unless the appropriate resources are immediately available, such as an operating room, a properly trained surgeon, etc. since the procedure is a temporizing measure meant to deliver the patient to definitive treatment.

- A thoracotomy could also be considered contraindicated when being performed without the necessary equipment, including a manual internal defibrillator.

- Penetrating abdominal trauma without cardiac activitY (prehospital)

- Severe head injury

- Severe multisystem injury

Equipment

A sterile thoracotomy tray is required: Sterile drapes and towels, laparotomy sponges, scalpel holder, scissors, rib spreader, aortic cross-clamp, variety of hemostatic clamps, tissue forceps, sutures, Teflon pledgets, and needle drivers. A 20F Foley catheter with a 30-ml balloon is an optional adjunct to be used to control bleeding. Adequate lighting and suctioning as well as operating room assistants, are extremely helpful, but not always readily available. A manual internal defibrillator should also be available since this is performed in the setting of an active resuscitation. Once the chest is open, external defibrillators are much less effective. A 30F chest tube is also needed.

Personnel

One person should be dedicated to continuing standard resuscitative efforts, including advanced cardiac life support (ACLS), in addition to the usual extra personnel to assist them. One person should be dedicated to performing the thoracotomy, and if possible, should have an assistant. A pathway to definitive care, such as a surgeon and trauma team with the appropriate operating room personnel, should be available for continued treatment after the procedure.

Preparation

An emergency room thoracotomy is an emergent procedure that will offer little time for preparation when needed. The majority of the preparation should be performed before the procedure is required. A provider should know when the necessary tools are and how to use them. Additionally, the provider should be well versed in the procedure steps and indications. All personnel and equipment should be gathered and ready before starting the procedure. Antibiotics are recommended before any cardiothoracic surgery; however, resuscitative thoracentesis should not be delayed waiting for antibiotics. Universal precautions should be followed with gowns, gloves, and eye protection for any personnel involved in the resuscitative efforts.

Technique or Treatment

The patient should be positioned supine with both arms abducted and extended to 90 degrees. Generally, a left-sided approach is used, since this provides access to the left thorax, pericardium, heart, and aorta. A skin incision is made with a #10 blade scalpel, from the sternum through the 4 or 5 intercostal space below the nipple, and continued laterally to the posterior mid-axillary line following the curve of the ribs. Female patients should have their breasts retracted superiorly. The initial incision should incise through the skin and subcutaneous fat and can be continued to the ribs on thin patients. If bleeding from the right thorax is suspected, a right-sided approach can be utilized. An incision can be extended from left to right, below the sternum, to make a clamshell incision which exposes the anterior mediastinum, aortic arch, and great vessels. There is a debate going on regarding the best approach, and some contend that for the average emergency provider who is less accustomed to the procedure and with incomplete information regarding the extent of injuries, the clamshell incision should be the preferred approach.[13]

A 1-2 inch incision should be made laterally (to avoid damaging the heart) along the superior margin of the inferior rib (to avoid the intercostal neurovascular bundles). The incision should penetrate and separate the intercostal muscles and underlying pleura, being careful not to injure the underlying lung tissue. Mayo scissors (or sterile trauma shears) are then used to complete the incision from the initial defect and directed anteriorly towards the sternum, separating the intercostal muscles. The incision is completed by cutting posteriorly toward the posterior mid-axillary line.

After entering the chest, rib spreaders are inserted between the ribs with the arm directed toward the axilla and the ratchet bar down. Then the rib spreader is expanded maximally to optimize exposure.

After entering the chest, optional right-sided main-stem bronchus intubation may aid in reducing left lung ventilation and further maximizing exposure. Any visible bleeding should be controlled with direct pressure or laparotomy sponges. Clamps should be used only as a last resort. Bleeding from major pulmonary vasculature can be controlled by directly clamping the injured lung tissue or vessel, clamping the pulmonary hilum, or using the “pulmonary hilar twist” maneuver (the last two also reduce the potential for air embolism).

If no pericardial effusion or apparent pericardial injury is present, further damage control is reasonable before pericardiotomy. Open cardiac massage can be performed with the pericardium intact. If the myocardium cannot be visualized through the pericardium, pericardiotomy should be performed, and the heart should be delivered out fo the pericardial sac. The phrenic nerve should be identified along the lateral pericardium and protected from injury during the pericardiectomy. The pericardium should be grasped with toothed forceps and a small incision made with either a scalpel or scissors, avoiding damage to the myocardium and the phrenic nerve. This incision is extended parallel to the phrenic nerve superiorly and should expose the great vessels. Pericardial fluid and clots should be removed, then evaluate the great vessels. Following this, the heart is delivered through the pericardial sac. The heart is palpated for any injury and inspected for any bleeding or hemorrhaging. Bleeding is initially controlled with direct pressure. If direct pressure is not sufficient or hemorrhaging is too brisk, escalating techniques include ligation with suture, closing a laceration with staples, or inserting the tip of a Foley catheter, inflating the balloon, and retraction to apply internal compression. The foley is best used for a laceration that punctures a ventricle where the foley tip and balloon can be inserted into the defect, and the balloon inflated. If there is a superficial laceration to the myocardium or one of the cardiac vessels is lacerated, temporary repair with sutures or staples should temporize the bleeding long enough for the patient to be stabilized and transported to the operating theater.

Next, the aorta is typically cross clamped to improve intracranial blood flow. Avoid cross-clamping the aorta in normotensive patients because of elevated afterload which compromises cardiac circulation.[14] The left lung is retracted superiorly, and the pulmonary ligament is divided. The esophagus can be differentiated from an empty aorta by palpating a nasogastric or orogastric tube within the esophagus. The overlying pleura is separated, and the aorta is liberated from the esophagus, spine posteriorly, and enough space is created for cross-clamping. The aorta should be cross-clamped in an intervertebral space to avoid damaging intercostal vessels. The aorta is clamped just above the diaphragm ideally but can also be clamped just below the left pulmonary hilum. After the aorta is clamped, ACLS and ATLS can continue with open cardiac massage and internal defibrillation as needed.

Hemorrhage repair is typically temporizing, meant to deliver the patient to definitive repair within the operating room. Direct bleeding from the heart can be controlled with direct digital pressure, simple suturing, or staples. If a significant defect is present, balloon occlusion can be used to achieve hemostasis by inserting a Foley catheter into the defect, inflating the balloon with saline, and withdrawn until tamponade is achieved. Additional bleeding should be controlled with direct pressure or laparotomy sponges.

Complications

Emergency room thoracotomy is a life-saving procedure; however, its benefit should be weighed against its complications.

- One of the most frequent complications is operator injury, and the first and foremost precaution should be utilizing the correct personal protective equipment (PPE). Occupational exposures to human immunodeficiency virus or other blood-borne diseases are slightly higher than average, but strict usage of PPE dramatically reduces the risks of exposure.[15]

- During the primary incision, ribs can be transected, creating sharp edges that can puncture or lacerate the operator. A curvilinear incision following the contour of the ribs is essential to minimizing this risk. Additionally, if a scalpel is used to incise completely into the thorax, the pericardium and underlying structures can be further damaged. These iatrogenic injuries are most easily avoided by utilizing Mayo scissors to separate the intercostal muscles and soft tissues.

- During pericardiotomy, coronary arteries can be accidentally ligated or, more commonly, the phrenic nerve can be transacted. A functional understanding of anatomy and the techniques to be performed are essential to minimize the risk of accidental structural injury.

- Complete exposure of the aorta is essential to prevent incomplete cross-clamping of the aorta, clamping the esophagus with the aorta, or exclusively clamping the esophagus.

- Damage to the phrenic nerve

- Ischemia to distal organs due to cross-clamping of the aorta

- Recurrent bleeding from the chest wall or internal mammary artery

Clinical Significance

Over the last 40 years, the indications for emergent thoracotomy have been refined in response to improved data and results. Currently, in the right population, this procedure has shown excellent results in the mortality reduction in specific circumstances. Overall, however, morbidity and mortality are high, with a survival rate ranging from 7.4 to 8.5 percent depending on the mechanism of injury.[16]

Significant factors contributing to morbidity and mortality rates include mechanism and magnitude of the injury, location of the injury, and signs of life. Survival is decreased in pediatric cases as well as blunt thoracic trauma as compared to penetrating.[17] Currently, there is no strong consensus if emergent thoracotomy should be attempted in most cases of blunt trauma due to the low survival rates.[18][19] Up to date, information on the indications, techniques, and contraindications are important and will lead to better utilization of resources and a decrease in futile procedures.[20]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Emergency room thoracotomy is a last resort effort for life-saving treatment in a specific patient population. The resuscitation of patients who qualify for emergency room thoracotomy will, at a minimum, involve an emergency provider, nurses, and potential assistants, technicians, or any other available staff. It is not a procedure that can be performed in isolation, and a unified, focused team will improve outcomes. Often there will also be a trauma surgeon, as well as their support staff, also present for the procedure. Otherwise, the surgical team will be involved directly after the procedure for definitive treatment in the operating room.

Definite indications for patients who qualify for this last-resort attempt will help improve outcomes by reducing efforts in hopeless cases with other unsurvivable injuries. Additionally, a review of the steps involved in the procedure and expected next-steps can enhance the efficiency of interprofessional communication. [Level 4]

Media

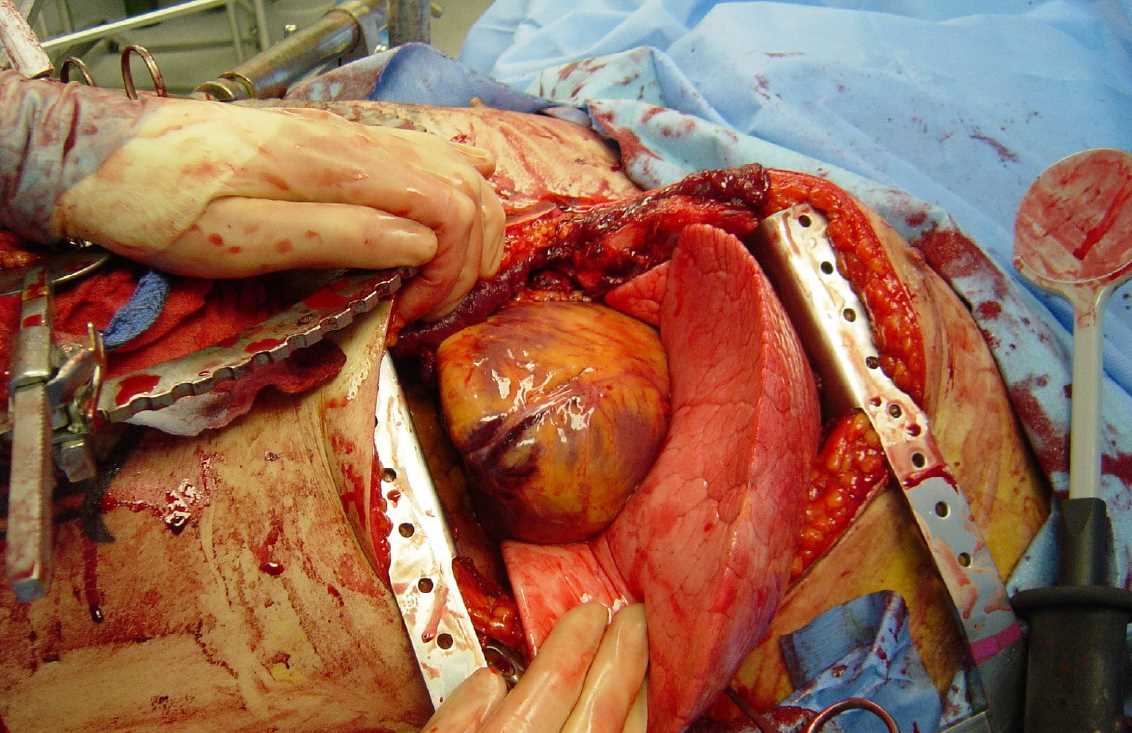

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

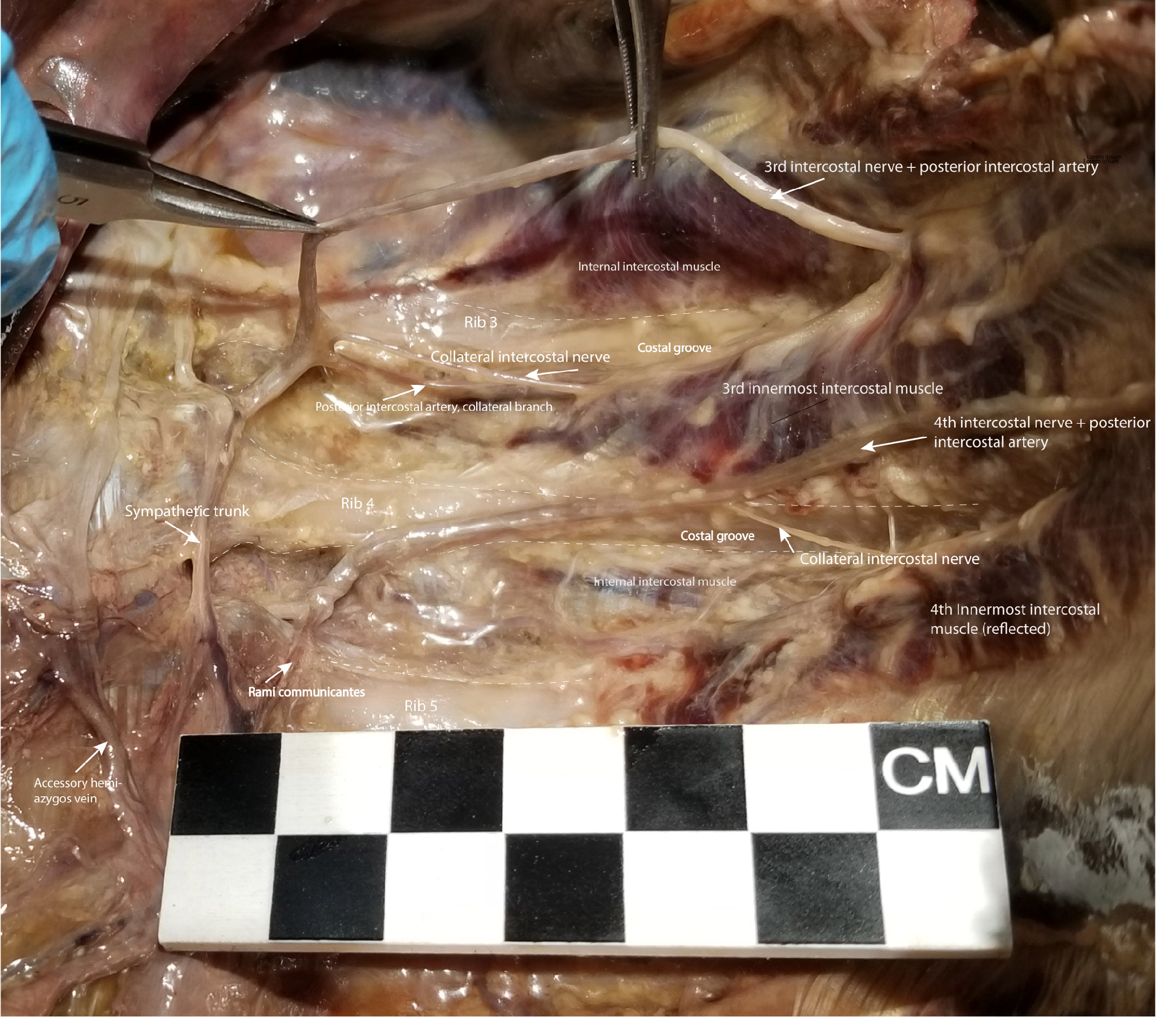

Dissection of the Left Posterior Thoracic Wall Showing Intercostal Spaces 3 and 4. The intercostal neurovascular bundle, including intercostal nerve 3, has been elevated from its location in the costal groove to demonstrate the branching of the collateral intercostal nerve near the angle of the rib. The collateral intercostal nerve is subject to injury in thoracotomy in its location immediately superior to the rib. To avoid injuring the intercostal nerve or its collateral branch, the optimal entry point surgically into the intercostal space is midway between its superior and inferior borders.

Contributed by NT Boaz, MD. Dissection by K Meshida, R Bernor, and NT Boaz, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kirkpatrick AW, Ball CG, D'Amours SK, Zygun D. Acute resuscitation of the unstable adult trauma patient: bedside diagnosis and therapy. Canadian journal of surgery. Journal canadien de chirurgie. 2008 Feb:51(1):57-69 [PubMed PMID: 18248707]

Menaker J, Cushman J, Vermillion JM, Rosenthal RE, Scalea TM. Ultrasound-diagnosed cardiac tamponade after blunt abdominal trauma-treated with emergent thoracotomy. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2007 Jan:32(1):99-103 [PubMed PMID: 17239739]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLeidel BA, Kanz KG, Kirchhoff C, Bürklein D, Wismüller A, Mutschler W. [Cardiac arrest following blunt chest injury. Emergency thoracotomy without ifs or buts?]. Der Unfallchirurg. 2007 Oct:110(10):884-90 [PubMed PMID: 17909734]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBoczar ME, Howard MA, Rivers EP, Martin GB, Horst HM, Lewandowski C, Tomlanovich MC, Nowak RM. A technique revisited: hemodynamic comparison of closed- and open-chest cardiac massage during human cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Critical care medicine. 1995 Mar:23(3):498-503 [PubMed PMID: 7874901]

Jackson RE, Freeman SB. Hemodynamics of cardiac massage. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 1983 Dec:1(3):501-13 [PubMed PMID: 6396069]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYamamoto R, Suzuki M, Nakama R, Kase K, Sekine K, Kurihara T, Sasaki J. Impact of cardiopulmonary resuscitation time on the effectiveness of emergency department thoracotomy after blunt trauma. European journal of trauma and emergency surgery : official publication of the European Trauma Society. 2019 Aug:45(4):697-704. doi: 10.1007/s00068-018-0967-y. Epub 2018 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 29855670]

Lau HK, Chua ISY, Ponampalam R. Penetrating Thoracic Injury and Fatal Aortic Transection From the Barb of a Stingray. Wilderness & environmental medicine. 2020 Mar:31(1):78-81. doi: 10.1016/j.wem.2019.09.004. Epub 2020 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 31983600]

Seamon MJ, Haut ER, Van Arendonk K, Barbosa RR, Chiu WC, Dente CJ, Fox N, Jawa RS, Khwaja K, Lee JK, Magnotti LJ, Mayglothling JA, McDonald AA, Rowell S, To KB, Falck-Ytter Y, Rhee P. An evidence-based approach to patient selection for emergency department thoracotomy: A practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2015 Jul:79(1):159-73. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000648. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26091330]

Gao JM, Du DY, Kong LW, Yang J, Li H, Wei GB, Li CH, Liu CP. Emergency Surgery for Blunt Cardiac Injury: Experience in 43 Cases. World journal of surgery. 2020 May:44(5):1666-1672. doi: 10.1007/s00268-020-05369-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31915978]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFarooqui AM, Cunningham C, Morse N, Nzewi O. Life-saving emergency clamshell thoracotomy with damage-control laparotomy. BMJ case reports. 2019 Mar 4:12(3):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-227879. Epub 2019 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 30837237]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMoskowitz EE, Burlew CC, Kulungowski AM, Bensard DD. Survival after emergency department thoracotomy in the pediatric trauma population: a review of published data. Pediatric surgery international. 2018 Aug:34(8):857-860. doi: 10.1007/s00383-018-4290-9. Epub 2018 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 29876644]

Gil LA, Anstadt MJ, Kothari AN, Javorski MJ, Gonzalez RP, Luchette FA. The National Trauma Data Bank story for emergency department thoracotomy: How old is too old? Surgery. 2018 Mar:163(3):515-521. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.12.011. Epub 2018 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 29398037]

Simms ER, Flaris AN, Franchino X, Thomas MS, Caillot JL, Voiglio EJ. Bilateral anterior thoracotomy (clamshell incision) is the ideal emergency thoracotomy incision: an anatomic study. World journal of surgery. 2013 Jun:37(6):1277-85. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-1961-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23435679]

Garcia-Rinaldi R, Defore WW, Mattox KL, Beall AC Jr. Unimpaired renal, myocardial and neurologic function after cross clamping of the thoracic aorta. Surgery, gynecology & obstetrics. 1976 Aug:143(2):249-52 [PubMed PMID: 941082]

Nunn A, Prakash P, Inaba K, Escalante A, Maher Z, Yamaguchi S, Kim DY, Maciel J, Chiu WC, Drumheller B, Hazelton JP, Mukherjee K, Luo-Owen X, Nygaard RM, Marek AP, Morse BC, Fitzgerald CA, Bosarge PL, Jawa RS, Rowell SE, Magnotti LJ, Ong AW, Brahmbhatt TS, Grossman MD, Seamon MJ. Occupational exposure during emergency department thoracotomy: A prospective, multi-institution study. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2018 Jul:85(1):78-84. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001940. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29664893]

Dayama A, Sugano D, Spielman D, Stone ME Jr, Kaban J, Mahmoud A, McNelis J. Basic data underlying clinical decision-making and outcomes in emergency department thoracotomy: tabular review. ANZ journal of surgery. 2016 Jan-Feb:86(1-2):21-6. doi: 10.1111/ans.13227. Epub 2015 Jul 14 [PubMed PMID: 26178013]

Hoth JJ, Scott MJ, Bullock TK, Stassen NA, Franklin GA, Richardson JD. Thoracotomy for blunt trauma: traditional indications may not apply. The American surgeon. 2003 Dec:69(12):1108-11 [PubMed PMID: 14700301]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKhorsandi M, Skouras C, Shah R. Is there any role for resuscitative emergency department thoracotomy in blunt trauma? Interactive cardiovascular and thoracic surgery. 2013 Apr:16(4):509-16. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivs540. Epub 2012 Dec 28 [PubMed PMID: 23275145]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSlessor D, Hunter S. To be blunt: are we wasting our time? Emergency department thoracotomy following blunt trauma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of emergency medicine. 2015 Mar:65(3):297-307.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.08.020. Epub 2014 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 25443990]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDuBose J, Fabian T, Bee T, Moore LJ, Holcomb JB, Brenner M, Skarupa D, Inaba K, Rasmussen TE, Turay D, Scalea TM, AAST AORTA Study Group. Contemporary Utilization of Resuscitative Thoracotomy: Results From the AAST Aortic Occlusion for Resuscitation in Trauma and Acute Care Surgery (AORTA) Multicenter Registry. Shock (Augusta, Ga.). 2018 Oct:50(4):414-420. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001091. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29280925]