Introduction

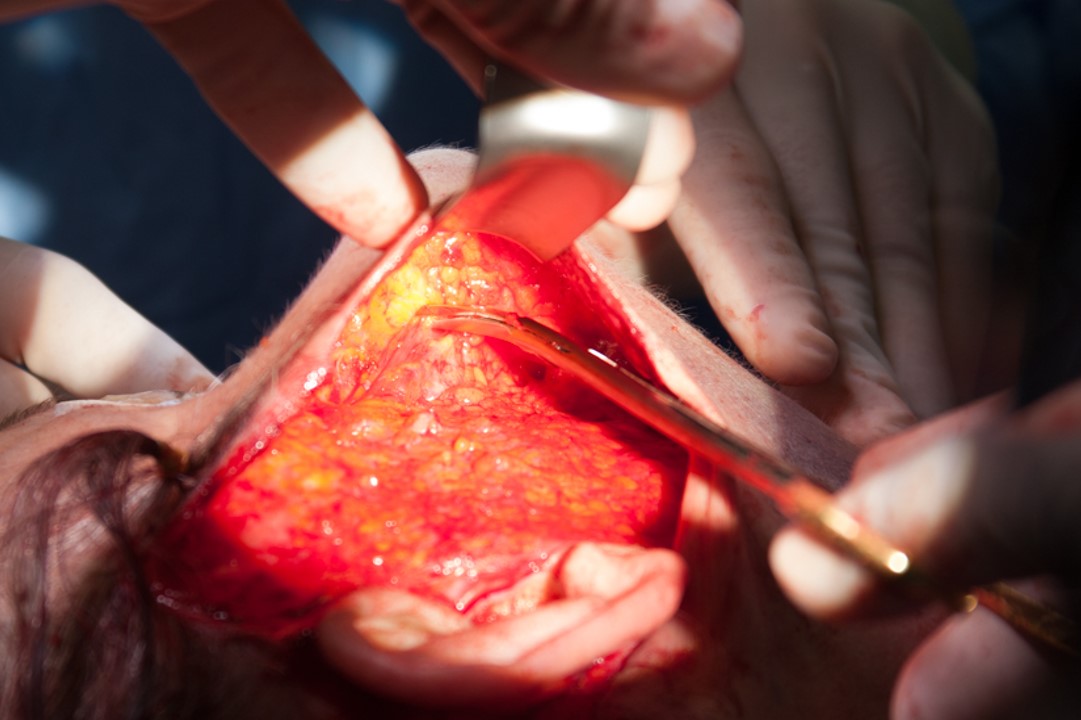

The deep plane facelift, originally described by Sam Hamra in 1990, utilizes a plane of dissection below the superficial muscular aponeurotic system (SMAS) of the midface, allowing for direct lysis of key facial retaining ligaments and maximum mobilization of the superficial soft tissue.[1] By placing tension only at the level of the fascia, the deep plane technique creates a tension-free skin closure and ensures long-term results. Additionally, the deep plane technique can also address pseudo-herniated buccal fat contributing to jowling. With that said, the debate continues as to which facelift technique is superior. Nevertheless, a properly executed deep plane facelift can produce dramatic and sustainable rejuvenation to the lower face and the midface.[2] See Image. Deep-Plane Facelift.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Primary Factors Contributing to the Aging of the Midface[3][4]

- Gravity: posited to be the central factor in facial aging secondary to its downward pull on the poorly anchored superficial soft tissue envelope.

- Volume loss: includes fat, muscle, and bone loss

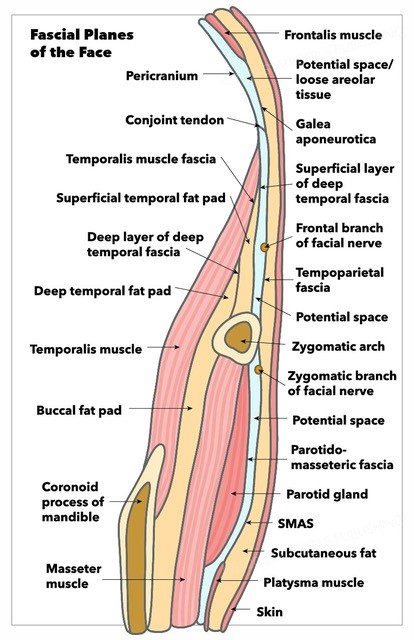

- Superficial cervical fascia: encompasses the majority of superficial facial fat and is continuous with the platysma muscle in the neck, SMAS in the midface, and galea in the upper face.

- Superficial musculoapeneurotic system: a fibrofatty layer that lies superficial to the parotidomasseteric fascia (which is contiguous with the deep cervical fascia), and is itself contiguous with the platsyma inferiorly, the temporoparietal fascia superior to the zygomatic arch, and the mimetic muscles medially.[7]

- Deep cervical fascia: covers the deeper structures of the face, including the masseter, facial nerve, and buccal fat pad.

- Deep plane: this is the embryologic cleavage plane that separates the superficial soft tissue envelope (covered by the superficial cervical fascia) from the deeper structural aspects of the face (encompassed by the deep cervical fascia).

- Key retaining ligaments of the face and neck: zygomatic (strongest of all the facial retaining ligaments), maxillary, masseteric, mandibular, and cervical.[8]

- Facial nerve: at risk for injury during facelift dissection, particularly at the temporoparietal, pre-parotid, and mandibular angle regions; the facial nerve runs deep to the SMAS and the mimetic muscles, except for the levator anguli oris, buccinator, and mentalis.

- Great auricular nerve: sensory nerve coursing over the body of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, located approximately 6.5 cm below the external auditory canal.[9] See Figure. Fascial Planes of the Face.

Indications

Areas of the midface able to be addressed by the deep-plane facelift technique[5][6]:

- Malar fat pad descent

- Nasolabial folds

- Jowling: a result of pseudo-herniated buccal fat and descent of the mobile, medial SMAS

- Festoons (malar mounds): hammocks of lax skin and orbicularis muscle that form large bags typically resting below the orbital rim

- Facial dimples: caused by fascial bands from the zygomatic major muscle (minor dimple) or a bifid zygomaticus major muscle (major dimple)

Contraindications

Increased Risk of Hematoma[6]

- Patients taking anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- Patients taking herbal medications and supplements such as chondroitin, ephedra, echinacea, glucosamine, ginkgo biloba, goldenseal, milk thistle, ginseng, kava, turmeric, and garlic

- Men (relative contraindication): twice as likely to experience hematoma (up to 8%)

- Poorly controlled hypertension, both pre-operatively and intra-operatively.

Active Smokers

Skin flap necrosis is 12 times more common in smokers who undergo any type of facelift. Note: this common dictum may not hold true for the deep plane technique.[10]

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD)

A psychiatric condition classified as an obsessive-compulsive–related disorder, where patients exhibit an obsessive preoccupation with perceived defects in their appearance that are either minute or absent. Moreover, patients with BDD tend to have poor satisfaction following surgery and show a higher rate of aggression and litigation toward surgeons. The prevalence of BDD may be as high as 13% in patients who present for a facial plastic surgery consultation.[11][12]

Equipment

Preoperatively

- Local anesthesia, such as 1 to 1 mix of 1% lidocaine with 1 to 100,000 epinephrine, with 0.5% bupivacaine with 1 to 200,000 epinephrine. Note: tumescent anesthesia may be an option in the areas of proposed skin flap elevation.

- Topical antiseptic, such as povidone-iodine paint

Intraoperatively

- Bipolar cautery

- Scalpel

- Tissue scissors

- Multi-prong retractors

- Facelift scissors

- Lighted retractor

- Closed suction drain with bulb

- Suture for SMAS suspension (3-0 or 4-0) and skin closure (4-0 and 5-0 nylon, 4-0synthetic absorbable sterile surgical suture)

- Stapler (may be used for hairline closure)

Postoperatively

- Antibiotic ointment

- Compressive dressing material

Personnel

- Anesthesiologist

- Surgical scrub technician

- Operative nurse (circulator)

- A surgical assistant is useful to help retract, manage intraoperative bleeding, and cut suture.

Preparation

Medical clearance: risk stratification and medical optimization for general anesthesia are necessary. Patients with an history of depression should be counseled that depression may recur during the postoperative period.

Neurologic examination: trigeminal and facial nerve function requires documentation.

Pre-operative photography: static and dynamic images in a frontal, three-quarter, and lateral views should adequately document ear position/shape, facial asymmetries, hairlines, and patterns of muscle action. The "chin-down" position is very useful to assess the effectiveness of any facelift on the cervico-mental angle and the neck in general.

The surgeon should mark the incisions in the temporal hairline (to ensure maximal preservation of hairline) and post-tragal (pre-auricular in men to avoid transplanting hair-bearing skin onto the tragus). A retro-auricular incision and occipital hairline incision may be needed depending on the amount of planed dissection and skin redundancy.

Important landmarks are identified including the trajectory of the temporal branch of the facial nerve (0.5 cm inferior to the tragus to 1.5 cm superior to the lateral brow[13]) and the deep plane entry point (a diagonal line from angle of the mandible to lateral canthus).

Anesthesia: although the deep plane facelift may be performed entirely under local anesthesia, general anesthesia or intravenous techniques (i.e., propofol) are advisable to ensure patient comfort. Muscle relaxants are avoided to allow monitoring of the facial nerve.

Administration of a single dose of intravenous antibiotics covering skin flora should take place pre-operatively.

A single dose of an intravenous steroid injection (i.e., 8 mg of dexamethasone) may help with swelling.

Local anesthesia is infiltrated along the proposed incision lines and beneath the area of planned subcutaneous dissection.

Technique or Treatment

Since the original description of the deep plane rhytidectomy, several modifications have been made by various authors to further improve rejuvenation of the midface, jawline, and neck (see Image. Deep Plane Rhytidectomy).[3][14][15][16] Herein, this activity will outline the basic surgical principles involved in performing a safe and reproducible midface lift using the contemporary deep plane (sub-SMAS) technique.

Incisions are as outlined above.

A subcutaneous flap is elevated uniformly slightly anterior to the marked deep plane entry point using a combination of sharp dissection (facelift scissors or scalpel), a multi-prong retractor, direct counter-tension, and backlighting of the flap. The postauricular skin is then dissected in a similar subcutaneous fashion and connected to the anterior facial dissection with care not to injury the great auricular nerve overlying the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

The deep plane is then entered by incising the SMAS sharply from just above the angle of the mandible to the lateral orbital rim.

The composite skin/SMAS flap is then carefully elevated off the parotid–masseteric fascia. There is a natural glide plane between the SMAS and the parotid-masseteric fascia. The masseteric ligaments, located at the anterior border of the masseter are released, and dissection is carried anteriorly towards the oral commissure until the surgeon identifies the facial artery.

The elevation of the deep plane is then focused superiorly by developing a pocket superficial to the lateral orbicularis oculi. This dissection is carried medially into the premaxillary space and nasofacial crease, where the composite flap transitions from skin/SMAS to skin/malar fat pad. The superficial aspect of the zygomatic major muscle is clearly identified during this step.

Sharp release of the zygomatic ligaments (now isolated between the superior and inferior deep plane pockets) is performed with care to stay superficial to the zygomatic muscle to protect the facial nerve branches innervating the muscle from below.

Dissection continues inferiorly along the zygomatic muscles to the nasolabial fold where the surgeon performs the release of the maxillary ligament, completing the midface release.

If excessive jowling exists due to buccal fat pseudo-herniation, this may be addressed at this time. With an assistant applying pressure to the buccal fat pad transorally, a small incision is made sharply in the overlying fascia. A conservative amount of buccal fat is then teased out and excised using bipolar cauterization with care to avoid injury to the buccal branches of the facial nerve which run around this buccal fat pad.

The SMAS flap is then suspended, working inferiorly to superiorly, with several half-mattress sutures (4-0 nylon or 3-0 polypropylene) placed along the cuff of SMAS at the deep plane entry point and anchored to the parotid and deep temporal fascia in a vertically oblique vector of about 60 degrees.[17]

After resuspension of the SMAS, the redundant skin is meticulously excised and suspended in a similar vector as the deep-plane flap to allow a tension-free skin closure. A combination of deep (4-0 Vicryl) and superficial (5-0 nylon) suture are options for closure with attention to preserving the continuity of the hairline by avoiding stepoffs during closure, everting the skin edges, excising bunched skin, and recreating a natural pre-auricular area hollow and tragus by thinning the skin prior to redraping the tragus and debulking the SMAS anterior to the tragal cartilage. A pixie ear deformity is avoided by ensuring a tension free closure inferior to the lobule.

Before final skin closure, a small drain is inserted through a stab incision posterior to the occipital hairline and placed under bulb suction.

Antibiotic ointment applied to the incision line, and placement of a compressive facelift dressing, complete the procedure.

Complications

The well-vascularized flap created by the deep-plane dissection provides increased protection against the potential problems associated with rhytidectomy; however, the following complications may occur[18]:

- Hematoma formation: occurs in less than 2% of cases; must be addressed promptly to prevent flap necrosis.

- Infections: occurs in less than 1% of cases

- Skin slough: occurs in less than 3% of cases; most commonly in the post-auricular location.

- Facial nerve injury: occurs in less than 1% of cases (similar for standard facelifts)

- Great auricular nervy injury: occurs in up to 7% of cases (most commonly injured nerve); causes lobule numbness

- Pixie-ear deformity: caused by excessive tension on the lobule during skin inset

- Alopecia: may be prevented with beveled hairline incisions and avoidance of cautery near the hairline

- First bite syndrome: uncommon, but may result from injury to symathetic nerve fibers in and around the parotid gland[19]

Clinical Significance

A deep plane facelift is a powerful tool that can restore a more youthful and rested appearance to the aging midface. When performing a deep plane facelift, proper patient evaluation, and execution of a thorough, anatomic-based treatment plan can produce safe, reliable, and satisfactory outcomes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

It remains imperative to identify the risk factors and perform a thorough assessment of the patient before performing a deep plane facelift. An interprofessional team approach is an ideal way to limit the complications of this procedure. Prior to surgery, the patient should have the following done:

- Evaluation by a surgeon experienced in selecting the appropriate patient for the deep plane facelift surgery

- Assessment by a primary care physician and/or anesthesiologist to ensure that the patient is fit for anesthesia

An interprofessional team of an experienced surgeon, anesthesiologist, and surgical assistants and operative nurses should be involved during the deep plane facelift to maximize outcomes. Close follow-up during the initial post-operative period, either by a wound care nurse and/or clinician experienced in the post-operative care of the deep plane facelift, should monitor the patient for possible complications including a hematoma or facial nerve deficits. It is also crucial to educate the patient on adequately maintaining the surgical wounds, and avoiding strenuous activity, heavy lifting, or bending over during the first several days post-operatively to help prevent complications. [Level 5]

Pharmacist involvement will include verifying dosing and agent selection for antibiotic prophylaxis, as well as pain medications and corticosteroids following the procedure, and performing medication reconciliation, reporting any concerns to the healthcare team. Nursing will assist in patient preparation for surgery, during the procedure, and in monitoring post-surgically, noting any concerns and letting the surgical team know. They are also front-line for verifying medication compliance and any potential adverse effects.

As can be seen from the above, deep plane facelifts require an interprofessional team approach, including physicians, specialists, specialty-trained nurses, and pharmacists, all collaborating across disciplines to achieve optimal patient results. [Level 5]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Adequate pain medication is necessary, as patients often report mild peri-incisional pain for three to four days postoperatively. To minimize edema and ecchymosis, the patient should wear the facelift dressing continuously for the first 24 hours, sleep with the head elevated for one week, and avoid rigorous activity for two weeks. The patient may be given a low-dose corticosteroid taper, Arnica montana, or bromelain to help lessen bruising and swelling as well, though definitive data on the efficacy of these measures is lacking.[6] Patients are asked to return at one day postoperatively for drain and dressing removal, and again at four days and seven days for further wound assessment and suture removal. Photographic documentation should occur at around nine to 12 months postoperatively.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Close follow-up during the initial post-operative period, either by a wound care nurse and/or clinician experienced in the post-operative care of the deep plane facelift, should monitor the patient for possible complications including hematoma formation and facial nerve deficits.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Fascial Planes of the Face and Musculature. This illustration depicts the fascial planes of the face, highlighting the continuity of the frontalis muscle, galea aponeurotica, temporoparietal fascia, superficial musculoaponeurotic system, platysma, and the location of the facial nerve.

Contributed by K Humphreys and MH Hohman, MD, FACS

References

Hamra ST. The deep-plane rhytidectomy. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1990 Jul:86(1):53-61; discussion 62-3 [PubMed PMID: 2359803]

Wulu JA, Spiegel JH. Is deep plane rhytidectomy superior to superficial musculoaponeurotic system plication facelift? The Laryngoscope. 2018 Aug:128(8):1741-1742. doi: 10.1002/lary.27065. Epub 2017 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 29280491]

Gordon NA, Adam SI 3rd. Deep plane face lifting for midface rejuvenation. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2015 Jan:42(1):129-42. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2014.08.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25440750]

Fitzgerald R, Graivier MH, Kane M, Lorenc ZP, Vleggaar D, Werschler WP, Kenkel JM. Update on facial aging. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2010 Jul-Aug:30 Suppl():11S-24S. doi: 10.1177/1090820X10378696. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20844296]

Jacono A, Bryant LM. Extended Deep Plane Facelift: Incorporating Facial Retaining Ligament Release and Composite Flap Shifts to Maximize Midface, Jawline and Neck Rejuvenation. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2018 Oct:45(4):527-554. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2018.06.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30268241]

Derby BM, Codner MA. Evidence-Based Medicine: Face Lift. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2017 Jan:139(1):151e-167e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002851. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28027252]

Mitz V, Peyronie M. The superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS) in the parotid and cheek area. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1976 Jul:58(1):80-8 [PubMed PMID: 935283]

Rossell-Perry P, Paredes-Leandro P. Anatomic study of the retaining ligaments of the face and applications for facial rejuvenation. Aesthetic plastic surgery. 2013 Jun:37(3):504-12. doi: 10.1007/s00266-012-9995-x. Epub 2012 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 23093328]

Lefkowitz T, Hazani R, Chowdhry S, Elston J, Yaremchuk MJ, Wilhelmi BJ. Anatomical landmarks to avoid injury to the great auricular nerve during rhytidectomy. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2013 Jan:33(1):19-23. doi: 10.1177/1090820X12469625. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23277616]

Parikh SS, Jacono AA. Deep-plane face-lift as an alternative in the smoking patient. Archives of facial plastic surgery. 2011 Jul-Aug:13(4):283-5. doi: 10.1001/archfacial.2011.39. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21768564]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJoseph AW, Ishii L, Joseph SS, Smith JI, Su P, Bater K, Byrne P, Boahene K, Papel I, Kontis T, Douglas R, Nelson CC, Ishii M. Prevalence of Body Dysmorphic Disorder and Surgeon Diagnostic Accuracy in Facial Plastic and Oculoplastic Surgery Clinics. JAMA facial plastic surgery. 2017 Jul 1:19(4):269-274. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2016.1535. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27930752]

Dey JK, Ishii M, Phillis M, Byrne PJ, Boahene KD, Ishii LE. Body dysmorphic disorder in a facial plastic and reconstructive surgery clinic: measuring prevalence, assessing comorbidities, and validating a feasible screening instrument. JAMA facial plastic surgery. 2015 Mar-Apr:17(2):137-43. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2014.1492. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25654334]

Pitanguy I, Ramos AS. The frontal branch of the facial nerve: the importance of its variations in face lifting. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1966 Oct:38(4):352-6 [PubMed PMID: 5926990]

Sykes JM, Liang J, Kim JE. Contemporary deep plane rhytidectomy. Facial plastic surgery : FPS. 2011 Feb:27(1):124-32. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1270426. Epub 2011 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 21246463]

Baker SR. Deep plane rhytidectomy and variations. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2009 Nov:17(4):557-73, vi. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2009.06.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19900662]

Choucair RJ, Hamra ST. Extended superficial musculaponeurotic system dissection and composite rhytidectomy. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2008 Oct:35(4):607-22, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2008.05.014. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18922313]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJacono AA, Ransom ER. Patient-specific rhytidectomy: finding the angle of maximal rejuvenation. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2012 Sep:32(7):804-13. doi: 10.1177/1090820X12455826. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22942107]

Jacono AA, Alemi AS, Russell JL. A Meta-Analysis of Complication Rates Among Different SMAS Facelift Techniques. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2019 Aug 22:39(9):927-942. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjz045. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30768122]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGunter AE, Llewellyn CM, Perez PB, Hohman MH, Roofe SB. First Bite Syndrome Following Rhytidectomy: A Case Report. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2021 Jan:130(1):92-97. doi: 10.1177/0003489420936713. Epub 2020 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 32567395]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence