Introduction

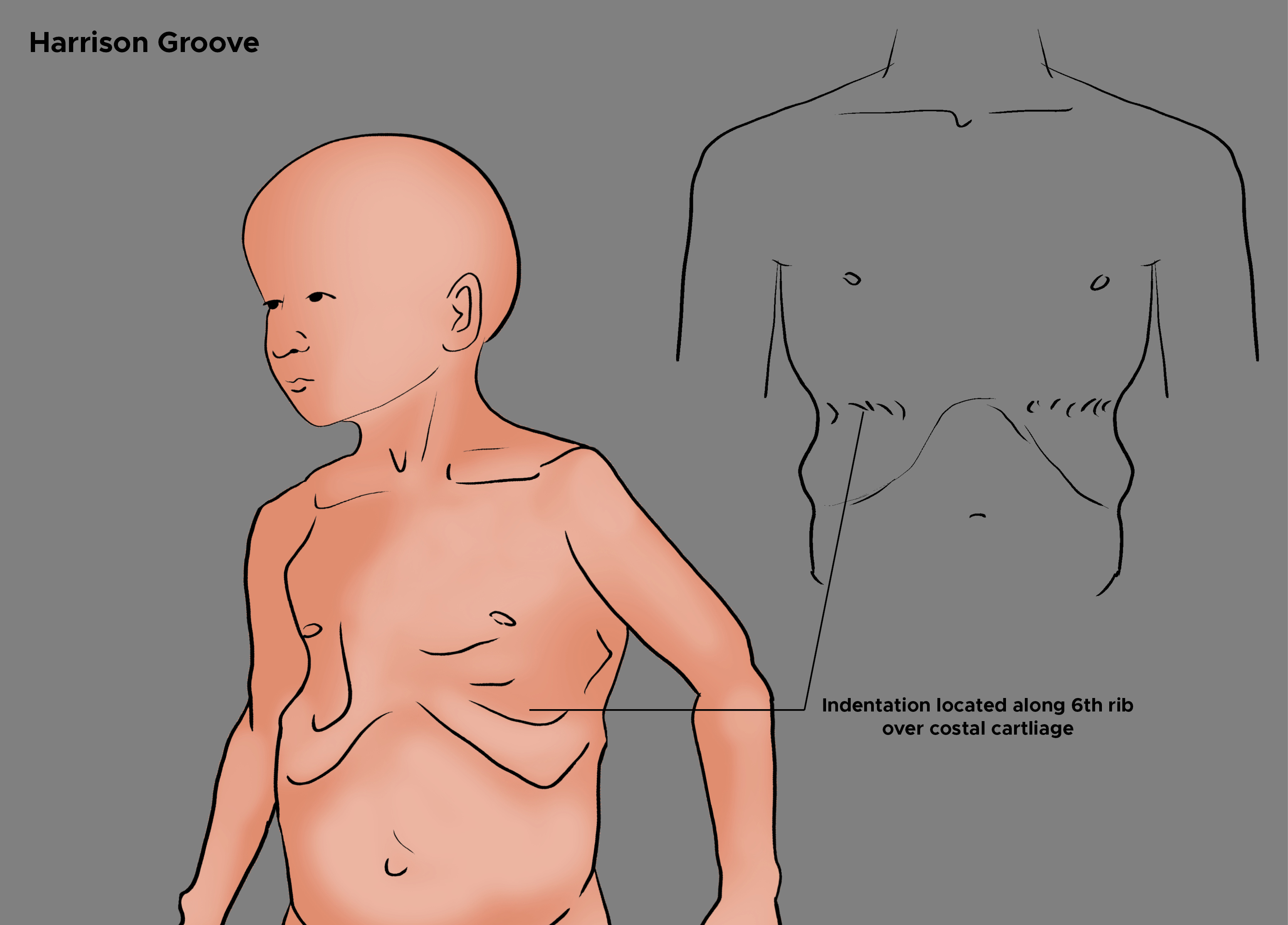

Harrison sulcus or Harrison groove is an indentation on the chest roughly along the 6th rib, which is usually bilateral but can also occur unilaterally. The groove's depth can vary from person to person, but the deepest part always remains over the sixth costal cartilage. See Image. Harrison Groove. It can be associated with other congenital chest deformities like pigeon breast and funnel chest. In an upright position, the groove is observed to start from the xiphoid and become shallower, eventually disappearing as it approaches the midaxillary line. The etiology of Harrison sulcus can be either idiopathic or secondary due to an underlying disease such as rickets, chronic malnutrition, recurrent pneumonia, chronic respiratory infections, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, unbalanced diaphragmatic contractions, and congenital heart disease.[1][2][3][4][5]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The formation mechanism of Harrison sulcus appeared to be due to the inward pull of ribs by the diaphragm along with its costal attachment. However, this mechanism has long since been challenged and is now rejected. Several authors have proposed more credible mechanisms, but they remain speculative. Experiments by Herlitz made an important observation that the diaphragm has no attachments along the groove and that the diaphragm pulls the lower rib in an upward direction.[6] The diaphragm attaches anteriorly to the xiphoid along with the level of the 7th rib and follows a diagonal path along the lower costal margins.[7]

He explains that the diaphragm lines the lower part of the thoracic wall due to the vacuum that exists between them and due to the abdominal organs pushing up on the diaphragm, preventing it from flattening, causing the pull of the diaphragm to be directed upwards. Therefore, he asserts that if the pull of the diaphragm was the cause of the groove, it would have pulled ribs up and outwards instead of inwards. He further noticed that the groove appeared along with the site where the diaphragm leaves the thorax to move inwards medially, also called the costo-phrenic sinus, which led him to believe that a strain is generated along the costo-phrenic sinus as the diaphragm tries to move away from the thoracic wall. This strain and retractive forces of the lungs may cause the groove to form.

On the other hand, Brodkin presents a mechanism similar to the 1 originally presented here.[1] He believes that the unbalanced contraction of the diaphragm is the underlying mechanism. Each hemidiaphragm consists of anterior, lateral, and posterior sections, of which the anterior portion is relatively weaker than the other 2. In healthy individuals, these muscles work harmoniously, balancing each other to maintain normal diaphragmatic function. In cases like asthma, pneumonia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the diaphragm has to work harder than usual to maintain the respiratory drive. The anterior section, being weaker, gives in and is pulled back by other sections of the diaphragm, which in turn draws the ribs back along with it. This concept has also been 1 of the key components for explaining the mechanism of forming a funnel chest, where unbalanced contractions along with a poor expansion of lungs in a premature infant due to clogged airways cause the sternum to bulge inward.[1][8][5]

Another consideration is that the groove is due to abnormal respiratory mechanics and physiology. The strain on the chest wall, the accentuated retractive forces of the lung, and the abnormal contraction of the diaphragm are all possible manifestations of physiological dysregulation.

Embryology

The diaphragm comprises the pleuroperitoneal membranes, a septum transversum, the dorsal mesentery of the esophagus, and muscular ingrowths from lateral body walls. The septum transversum is formed in the cervical region, adjacent to the third, fourth, and fifth somites. The myoblasts from these somites mature into the phrenic nerve and migrate caudally with the diaphragm to provide motor efferent and sensory afferent innervations.[9][10]

Many postulates make assumptions regarding the origination of the Harrison groove. It is most likely due to abnormal contractions of the diaphragm during infancy.[11] These contractions cause increased negative pressure that deforms the chondrosternal area where the anterior diaphragm attaches to it while the bones of the anterior chest wall are still malleable.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The diaphragm has a robust blood supply. Major arteries include the superior and inferior phrenic arteries, the branches of the aorta, the musculophrenic, and the pericardiacophrenic arteries. The musculophrenic and the pericardiacophrenic arteries are, in turn, branches of the internal thoracic artery and the lower internal intercostal arteries. The venous drainage from the diaphragm involves the brachiocephalic veins, azygos system, and veins that drain directly into the inferior vena cava and the left suprarenal vein.[10][12]

Nerves

The diaphragm receives motor innervation from the phrenic nerve. Fibers from the C3-C5 cervical spinal nerves form the phrenic nerve. Sensory innervation of the diaphragm is 2-fold. Sensory afferents are sent through the central portion of the diaphragm via the phrenic nerve and through the peripheral portion via the 6 most inferior intercostal nerves, T5-T11, and the subcostal nerve, T12. Injury to the phrenic nerve causes the diaphragm to lose the ability to contract. Due to the negative pressure within the thorax, the diaphragm remains elevated and unable to flatten on inspiration.[10][12] Harrison groove is not the result of a nerve injury; however, it has clinical application in determining the height of the diaphragm. If the phrenic nerve is injured and diaphragm contraction is impaired, then the Harrison groove can no longer be used as an approximation for the height of the diaphragm.

Muscles

The formation of the Harrison groove affects the diaphragm and the intercostal musculature significantly. Respiratory illness during infancy and early childhood, occurring before the maturity of these structures, creates a sulcus that lasts throughout childhood as an indicator of a chronic disease or past acute illnesses. The intercostal muscles make the Harrison groove more prominent as they pull the upper ribs upward and forward. In contrast, the lower ribs move outwards and backward to increase the transverse diameter of the thoracic cavity.

Physiologic Variants

Depth is the major variant seen between patients who have a Harrison groove. The assumption is that the depth is proportional to the severity of the early childhood disease that caused the Harrison groove to form. Increased depth may also indicate multiple respiratory illnesses during infancy and/or early childhood.

Surgical Considerations

Harrison groove is a harmless deformity that causes no debilitation or relevant restriction in the lung or diaphragmatic function. Therefore, no surgical indications for correction exist, except for cosmesis, especially with the unilateral groove. There is only 1 reported attempt on a 20-month-old girl with a unilateral groove.[1] The surgeon made a horizontal incision along the upper border of the sixth right cartilage. This incision freed it from its costal attachment, the soft tissue, and the seventh costal cartilage. These ribs sprang forward and above into a relaxed position. These were then sutured with wire into their respective normal positions, leading to the successful restoration of the shape of the chest.

Clinical Significance

Harrison groove can appear soon after birth in either premature infants who suffer from severe respiratory obstruction or newborns with weak diaphragmatic muscles. In such cases, the groove resolves once the chest clears and the diaphragm regains strength, respectively. Children in their first or second year also acquire this defect through pneumonia, asthma, or rickets. Here, the duration and number of episodes of pneumonia and asthma can play a role in determining the depth of the groove. Children with pneumonia in their first 2 years of life or experiencing more than 2 episodes reported having deeper grooves.[6] Children diagnosed with asthma of more than 4 years duration have also reportedly had a deeper Harrison groove, and that is more likely to become permanent.[11][13] Harrison grooves measuring 0.48 cm and deeper classify as severe.[11] Thus, early diagnosis and management can resolve the groove without becoming permanent.

Another patient population that Harrison grooves can occur in is patients with congenital heart diseases such as septal defects, Teratology of Fallot, and pulmonary stenosis.[6][13] In such patients, respiratory infections are the common factor and the most likely cause of groove.[13] Harrison groove has classically shown a correlation with rickets in the past. These were mostly children that had pigeon breast deformity. The belief is that the Harrison groove and pigeon breast are due to rickets. Instead, the suggestion is that since chest infections are common in rickets, the associated dyspnea leads to groove formation. Harrison groove has also presented in other diseases like whooping cough, bronchitis, and measles, but the incidences are too few to make any meaningful associations.[14][13]

It is important to remember that the Harrison groove is an unreliable sign. Harrison grooves can appear in normal, healthy children with no relevant history of any illness.[1][5] It is also true that, in many instances, the groove does not develop in any of these illnesses.[1][5][1] Naish and Wallis found that 45% of 500 healthy children surveyed had the groove with no significant medical history of any relevant disease.[6] Furthermore, they also report that children with the deepest groove lead completely healthy lives in infancy and childhood. Also, Brodkin argued that the presence of grooves associated with rickets is insignificant, suggesting that the groove and the disease may be a mere coincidence. Rickets may contribute to the groove's formation rather than causing it.[1][5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

BRODKIN HA. Etiology and mechanism of Harrison's grooves. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1956 Aug 18:161(16):1555-9 [PubMed PMID: 13345622]

Bovine G. Harrison's Grooves - Edwin Harrison (1779-1847) or Edward Harrison (1766-1838)? Journal of medical biography. 2015 Feb:23(1):17-9. doi: 10.1177/0967772013506679. Epub 2013 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 24585601]

DESHMUKH PL. Harrison's grooves. British medical journal. 1948 Jul 3:2(4565):51 [PubMed PMID: 18939068]

Tserendolgor U,Mawson JT,Macdonald AC,Oyunbileg M, Prevalence of rickets in Mongolia. Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition. 1998 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 24393693]

CLIFFORD SH. Postmaturity, with placental dysfunction; clinical syndrome and pathologic findings. The Journal of pediatrics. 1954 Jan:44(1):1-13 [PubMed PMID: 13131191]

HERLITZ G. What is the cause of Harrison's groove in rickety infants? Acta paediatrica. 1945:32(3-4):439-44 [PubMed PMID: 21007855]

Donley ER, Holme MR, Loyd JW. Anatomy, Thorax, Wall Movements. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252279]

GOOD R. Harrison's grooves. British medical journal. 1948 Apr 10:1(4553):707 [PubMed PMID: 18912702]

Sefton EM, Gallardo M, Kardon G. Developmental origin and morphogenesis of the diaphragm, an essential mammalian muscle. Developmental biology. 2018 Aug 15:440(2):64-73. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.04.010. Epub 2018 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 29679560]

Schumpelick V, Steinau G, Schlüper I, Prescher A. Surgical embryology and anatomy of the diaphragm with surgical applications. The Surgical clinics of North America. 2000 Feb:80(1):213-39, xi [PubMed PMID: 10685150]

NAISH J, WALLIS HR. The significance of Harrison's grooves. British medical journal. 1948 Mar 20:1(4550):541-4 [PubMed PMID: 18909481]

Downey R. Anatomy of the normal diaphragm. Thoracic surgery clinics. 2011 May:21(2):273-9, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2011.01.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21477776]

MAXWELL GM. Chest deformity in children with congenital heart disease. American heart journal. 1957 Sep:54(3):368-75 [PubMed PMID: 13458066]

Corner BD. The incidence of rickets in children attending hospitals in Bristol from September 1938 to May 1941. Archives of disease in childhood. 1944 Jun:19(98):68-86 [PubMed PMID: 21032276]