Introduction

Aphasia is an acquired language disorder caused by damage to the brain's language centers, characterized by difficulties in verbal or written expression, comprehension, or both. Most cases of aphasia involve a combination of these impairments, affecting multiple language functions. Common clinical types include Broca and Wernicke aphasia, conduction aphasia, transcortical motor or sensory aphasia, and alexia, with or without agraphia.

Although the primary cause of aphasia is stroke, particularly ischemic stroke, other causes include traumatic brain injury (TBI), brain tumors, and neurodegenerative diseases. Patients may present with symptoms such as difficulty articulating words, forming sentences, comprehension deficits, or a combination of these. Aphasia symptoms can range from mild impairment to a complete loss of fundamental language components, including semantics, grammar, phonology, morphology, and syntax. They may affect verbal communication, written language, or, more commonly, both.

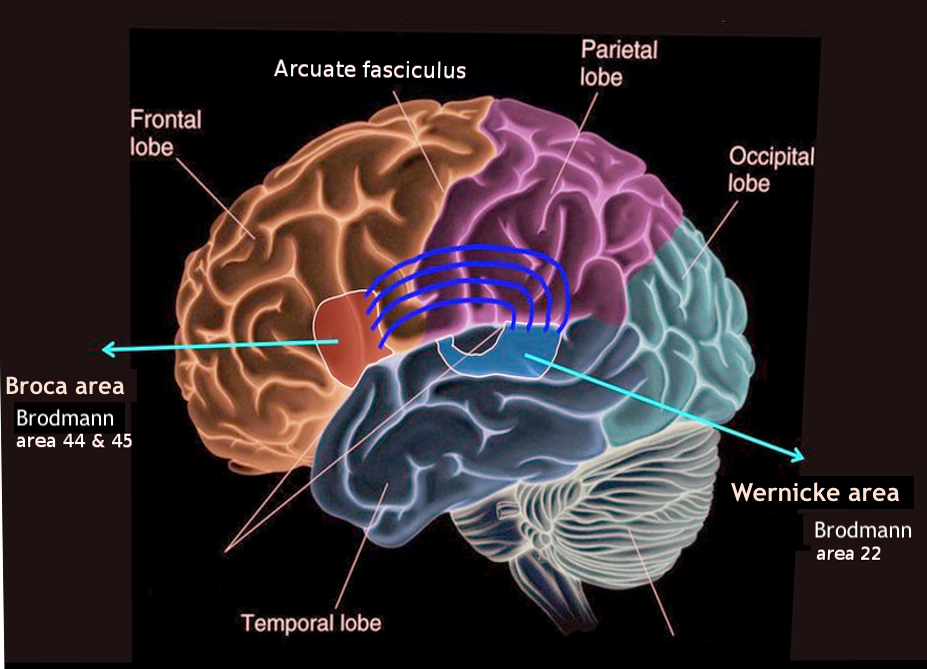

The classical model of aphasia was developed by Wernicke and Lichtheim in the 19th century and was further refined neuroanatomically by Geschwind in the 1960s.[1][2] This model provides the foundation for understanding aphasia's clinical features and the related neuroanatomical lesions. The brain's language centers are typically located in the dominant hemisphere, most often the left, within the peri-Sylvian region. Spoken language is received by the primary auditory cortices in the Heschl gyrus (transverse temporal gyrus) and processed in the Wernicke area in the posterior superior temporal gyrus. Written language is transmitted from the primary visual cortex in the occipital lobe to the angular gyrus and then to the Wernicke area.

The Broca area, located in the inferior frontal region, is responsible for the motor execution of speech and sentence formation.[3] The arcuate fasciculus is the neural pathway that connects the Wernicke area to the Broca area (see Image. The Broca and Wernicke Areas of the Brain).[4] According to the classical aphasia model, specific aphasia syndromes correspond to the location of the brain lesion.[5] A posterior lesion involving the Wernicke area results in fluent aphasia, characterized by impaired comprehension and severe paraphasia. In contrast, an anterior lesion affecting the Broca area leads to nonfluent aphasia, in which patients have normal comprehension but produce speech that is telegraphic, effortful, and dysprosodic, without paraphasic errors. A lesion in the arcuate fasciculus or the white matter tract connecting the Wernicke and Broca areas results in conduction aphasia, characterized by impaired repetition and phonemic paraphasia.

Global aphasia is the most common type of aphasia, impacting both language comprehension and expression to varying extents. Transcortical motor aphasia is a nonfluent type, similar to Broca aphasia, but with preserved repetition. Transcortical sensory aphasia is a fluent aphasia with impaired comprehension, resembling Wernicke aphasia but with intact repetition. Patients with transcortical motor or sensory aphasia often display excessive repetition, such as perseveration or echolalia. Anomia is a milder form of aphasia resulting from a small lesion in the dominant peri-Sylvian region.[1]

The contemporary language model, or the dual-stream model, was developed by Hickok and Poeppel,[6] and is supported by modern neuroimaging studies, including functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), diffusion tensor imaging, and MRI tractography. This dual-stream model outlines 2 main language processing streams involving cortical and subcortical structures, as mentioned below.

- The dorsal stream: This is located in the dominant hemisphere region and processes auditory-to-articulation information, connecting the frontal speech areas and the temporoparietal junction. This stream is crucial in fluent speech production. Lesional analysis indicates that the dorsal stream primarily involves the gray matter of the frontoparietal regions.

- The ventral stream: This is located in both temporal lobes and processes auditory-to-meaning information, which is essential for auditory comprehension. This stream encompasses much of the gray matter in the lateral temporal lobe.[7] Conduction aphasia results from lesions in gray matter, particularly in the area Spt (Sylvian fissure, parietal-temporal junction), a posterior region that is part of the dorsal stream, rather than from involvement of the white matter tract of the arcuate fasciculus.[8]

In addition to cortical language areas, subcortical structural lesions can also lead to aphasia by disrupting the connections within the cortical-subcortical language networks. However, these causes are generally rare. Lesions in the basal ganglia, thalamus, and cerebellum may occasionally result in aphasia. Typically, aphasia resulting from basal ganglia lesions is mild, characterized by impaired language expression, such as word fluency, while comprehension and repetition remain intact.[9]

Thalamic aphasia occurs when the left-sided ventral anterior or paramedian nuclei are affected and can be either fluent or nonfluent. This type of aphasia primarily results in lexical-semantic deficits, with relative preservation of repetition.[10] Rarely, cerebellar lesions on either side may lead to aphasia, typically characterized by deficits in word retrieval, semantics, and syntax.[11] Overall, subcortical aphasia tends to be milder and associated with a better prognosis.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Stroke, particularly ischemic stroke affecting the dominant hemisphere within the vascular territory of the left middle cerebral artery (MCA), is the most common cause of aphasia. A recent study reported an incidence of aphasia after acute ischemic stroke of 30%.[12] Other causes of aphasia include neurodegenerative diseases such as frontotemporal dementia or Alzheimer disease, TBI, or mass lesions in the brain, including primary or secondary brain tumors.

Aphasia is always the result of an acquired brain lesion, and it differs from dysarthria, which refers to impairment in articulation. Aphasia cannot be caused by diseases affecting the peripheral nervous system, neuromuscular junction, or muscles.

Epidemiology

According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), there are 180,000 new cases of aphasia in the United States each year, affecting 1 in every 272 Americans. Approximately one-third of these cases result from cerebrovascular accidents.[13] The most common type is global aphasia.[14] The incidence of stroke-induced aphasia is equal among men and women;[15] however, the incidence is age-dependent. Individuals aged 65 or younger have a 15% chance of being affected, whereas those aged 85 or older have a 43% chance of developing the condition.[16] Approximately 25% to 40% of stroke survivors experience aphasia due to damage to the brain's language-processing regions.

Pathophysiology

Aphasia is caused by lesions in the brain's language areas, typically located in the dominant hemisphere, which is the left hemisphere for most individuals.[17] Key areas include the Wernicke and Broca areas and arcuate fasciculus. According to the modern dual-stream neuroanatomic model of aphasia, damage to the dorsal stream, primarily within the frontoparietal regions, leads to nonfluent, effortful aphasia. In contrast, lesions affecting the ventral stream in the temporal areas result in fluent aphasia with comprehension deficits.

Conduction aphasia is most commonly associated with gray matter involvement in the Spt region, a part of the dorsal stream. Transcortical aphasia arises from disruptions in the connections between the brain's association areas and the peri-Sylvian language region. Alexia with agraphia, marked by an inability to read and write, results from a lesion in the dominant angular gyrus, posterior inferior temporal region, and adjacent supramarginal gyrus of the parietal lobe. Alexia without agraphia is caused by a small lesion affecting the dominant occipital lobe and the adjacent splenium of the corpus callosum.

Acute ischemic stroke is the most common cause of aphasia, with the dominant left MCA being the most frequently affected vascular territory. When the entire dominant MCA territory is involved, global aphasia typically results. Occlusion of the anterosuperior branch of the MCA typically leads to nonfluent Broca aphasia, also known as dorsal stream aphasia, characterized by predominant difficulties in language production while comprehension remains intact. In contrast, occlusion of the posteroinferior branch results in fluent Wernicke aphasia, or ventral stream aphasia, which is associated with notable comprehension deficits. Patients with this condition often experience difficulties with repetition, reading, and writing.

Transcortical aphasia often results from watershed infarctions caused by acute cerebral hypoxemia, such as severe hypotension or cardiac arrest. Transcortical motor aphasia arises from a watershed infarction between the anterior cerebral artery and MCAs, sometimes occurring with occlusion of the dominant internal carotid artery. Transcortical sensory aphasia is due to a watershed infarction between the dominant middle and posterior cerebral infarcts.[8] Additionally, aphasia can occasionally result from damage to subcortical structures deep within the left hemisphere, including the internal and external capsules, thalamus, and caudate nucleus.[18]

Aphasia can also result from TBI and neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal dementia. Primary progressive aphasia, a form of frontotemporal dementia, primarily presents with gradual language decline due to degeneration and neuronal loss in the brain's language areas. Additional causes of injury to language areas include infections and mass effects from brain tumors.[19]

History and Physical

When evaluating a patient with speech difficulties, the first step is to determine if the issue is aphasia, dysarthria, or dysphonia. Dysarthria affects articulation but does not affect comprehension, fluency, or expression and typically presents as slurred speech. Dysphonia means hoarseness of voice. When a patient presents with aphasia, the clinical evaluation should include a thorough history and physical examination, focusing on the assessment of fluency, comprehension, repetition, naming, reading, and writing. Additionally, evaluating the prosody (musical quality) of the patient's speech is crucial.

Comprehension is assessed by asking the patient to follow 1-step commands, progressing to 2-step and then 3-step commands. Examples include: "Can you close your eyes?" followed by, "Can you close your eyes and raise your left thumb?" and finally, "Can you close your eyes, raise your left thumb, and touch your nose?" Repetition can be evaluated by having the patient repeat sentences such as, "This is a beautiful day" or "No ifs, ands, or buts." Naming is assessed using both common and uncommon objects. By following this systematic sequence of examination, clinicians can often accurately diagnose various aphasic syndromes. These clinical aphasia syndromes are traditionally classified using widely accepted categories.

Wernicke Aphasia (Receptive)

The lesion associated with Wernicke aphasia is typically located in the Wernicke area (Brodmann area 22) or more posteriorly in the superior temporal gyrus, which serves as the center for comprehension and understanding of language.[20] Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Neuroanatomy, Wernicke Area," for more information. Patients exhibit fluent aphasia characterized by normal prosody. However, their comprehension and naming abilities are severely impaired, often accompanied by varying degrees of paraphasia, including literal paraphasia, phonemic paraphasia, and neologisms or jargon. Communicating with these patients can be challenging due to their comprehension deficits. Reading and writing abilities are similarly affected. Neologisms refer to made-up words, while jargon consists of a combination of neologisms and real words that lack coherent meaning in context. These patients are typically unaware of their errors and do not recognize that their speech lacks meaning.

Broca Aphasia (Expressive)

The lesion associated with Broca aphasia is located in the Broca area, specifically in the anterior part of the peri-Sylvian region of the inferior frontal gyrus, which is responsible for the motor aspects of speech and sentence formation and expression. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Neuroanatomy, Wernicke Area," for more information. Patients exhibit nonfluent, dysprosodic, and effortful speech that is often telegraphic, omitting conjunctions, prepositions, articles, adjectives, and adverbs. While comprehension remains normal, naming and repetition abilities are affected to varying degrees. Reading and writing skills mirror their verbal language capabilities. Despite the nonfluent nature of their speech and the absence of grammatically significant words, patients can typically convey their intended message by using essential content words such as nouns, verbs, and some adjectives.

Conduction Aphasia

The lesion associated with conduction aphasia is located in the arcuate fasciculus, the neural pathway connecting the Wernicke area to the Broca area.[4] More specifically, the lesion is situated in the gray matter of the area Spt, as previously described. Patients with conduction aphasia typically exhibit impaired repetition and phonemic paraphasia. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Conduction Aphasia," for more information.

Transcortical Sensory Aphasia

In transcortical sensory aphasia, the lesion is located around the Wernicke area while sparing and isolating it. Patients have impaired comprehension but can repeat speech fluently, leading to phenomena such as echolalia and perseveration. Additionally, these patients often exhibit semantic paraphasia.[21]

Transcortical Motor Aphasia

In transcortical motor aphasia, the lesion is located around the Broca area while sparing and isolating it. Patients exhibit nonfluent speech but can repeat long, complex phrases, often displaying echolalia and perseveration. Although they tend to remain silent, they may occasionally speak using 1 to 2 words.[21]

Global Aphasia

Global aphasia results from lesions that vary in size and location, primarily affecting the brain areas in the peri-Sylvian region supplied by the dominant left MCA. This is the most common and severe form of aphasia. Patients typically produce only a few recognizable words and exhibit little to no understanding of spoken or written language. Additionally, they are unable to read or write.

Anomia (Nominal Aphasia)

Anomia, also known as nominal aphasia, is a mild form of aphasia traditionally thought to arise from lesions affecting the dominant angular gyrus. However, it is now understood that even small or mild lesions in the language areas can lead to this condition. Patients primarily experience difficulties with word finding.[22]

Subcortical Aphasia

Aphasia resulting from basal ganglia lesions is generally mild, characterized by impaired language expression, such as word fluency, while comprehension and repetition remain intact.[9] Thalamic aphasia occurs when the left-sided ventral-anterior or paramedian nuclei are involved. This type of aphasia can be either fluent or nonfluent and primarily leads to lexical-semantic deficits, with relative preservation of repetition.[10] Cerebellar lesions on either side may rarely cause aphasia, typically manifesting as difficulties in word retrieval, semantics, and syntax.[11] Overall, subcortical aphasia tends to be milder and has a better prognosis.

Related Physical Examination Findings

Aphasia is associated with lesions localized in the dominant peri-Sylvian area of the brain, situated between the inferior frontal gyrus anteriorly and the superior temporal gyrus posteriorly. Consequently, patients often exhibit right hemiparesis, which particularly affects the faciolingual areas. Individuals with transcortical global or transcortical motor aphasia frequently present with right hemiparesis that primarily impacts the proximal muscles, resembling the symptoms seen in man-in-a-barrel syndrome.[23]

Evaluation

Patients suspected of having an acute stroke are typically evaluated with a non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan, followed by an MRI, to identify the precise location and nature of the lesion. Subsequently, speech-language pathologists assess the patient to identify specific areas and types of language deficits. Several formal assessments can diagnose aphasia, including the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination and the Western Aphasia Battery.

The Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination offers a severity rating ranging from slight to severe, whereas the Western Aphasia Battery determines whether the patient is aphasic and, if so, identifies the type and severity of aphasia. Additionally, it provides a baseline for future assessments, helping to track trends and improvements while highlighting the patient's strengths and weaknesses.[24]

The evaluation of aphasia involves 4 key components of language assessment to differentiate among various aphasia syndromes—fluency of speech, comprehension, confrontational naming, and repetition. Fluency of speech refers to the typical speech rate, intact syntactic ability, and effortless speech output. Comprehension assesses the patient's ability to understand both written and spoken language. Lastly, repetition evaluates the patient's capability to repeat written or spoken words.[25]

Fluent Aphasia Syndromes

- Wernicke aphasia: This condition is characterized by fluent speech and impaired comprehension. Patients exhibit various paraphasic errors, including phonemic, literal, and neologisms. In severe cases, this type of aphasia is referred to as jargon speech or word salad. Patients also have difficulties with naming and repetition.

- Transcortical sensory aphasia: This syndrome features fluent speech and impaired comprehension, but patients demonstrate exceptionally good repetition, often resulting in echolalia and perseveration.

- Conduction aphasia: Patients display fluent speech and intact comprehension but experience typical phonemic paraphasia and are unable to repeat.

- Anomic aphasia: Patients exhibit fluent speech and intact comprehension, with the ability to repeat words successfully.

Nonfluent Aphasia Syndromes

- Broca aphasia: This condition is characterized by nonfluent, telegraphic, effortful, and dysprosodic speech without paraphasic errors. Patients have intact comprehension, varying degrees of anomia, and are unable to repeat.

- Transcortical motor aphasia: This syndrome features nonfluent speech with intact comprehension and exceptionally good repetition, often resulting in echolalia and perseveration.

- Mixed transcortical aphasia: This condition is characterized by nonfluent speech with impaired comprehension but exceptionally good repetition, resulting in echolalia and perseveration.

- Global aphasia: This syndrome features nonfluent speech with impaired comprehension and inability to repeat. This is the most common and severe form of aphasia, typically resulting from an infarct in the dominant MCA territory.

A cognitive neuropsychological approach seeks to identify specific language skills, or "modules," that are not functioning properly. Patients may have impairments in one or multiple modules.

Treatment / Management

The initial treatment for aphasia involves addressing its underlying cause. For patients with acute ischemic stroke, options may include intravenous thrombolytic therapy with tissue plasminogen activator, tenecteplase (TNK), or intra-arterial mechanical thrombectomy.[26] Surgical decompression is indicated for patients with hemorrhagic stroke, TBI, or brain tumors. If an infection is the cause, initiating treatment with steroids, antivirals, or antibiotics may be necessary. Although there is no standardized treatment for aphasia, the primary goal is to help patients regain their highest level of independence. Achieving this requires addressing and managing the patient's physical comorbidities, mental health, and deficits. Additionally, caregiver education and social support significantly influence a patient's recovery outcome.(B2)

Patients with aphasia experience challenges in communicating their wants and needs. Many are aware of their deficits and circumstances, which can lead to frustration, severe depression, and reduced participation in therapy. Therefore, early diagnosis of depression is crucial for effectively treating aphasic patients. Emotional support from family, friends, and spiritual leaders is essential. Referrals to a psychiatrist, neuropsychologist, or psychologist for evaluation and management may also be necessary. Treatment for depression typically includes pharmacological management.[27] First-line medications include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), as well as tricyclic antidepressants. However, SSRIs are generally preferred due to lower adverse effect profiles.(A1)

Speech-language pathologists will assess patients to identify their strengths and weaknesses, allowing for the customization of individualized treatment plans. Research indicates that patients experience better improvement with short, intensive treatment sessions rather than longer, less intense ones.[28] Patients will also receive various compensatory strategies, such as augmentative and alternative communication. These strategies may include whiteboards, pens, and paper for writing, photos of common items for identification, or more advanced devices such as tablets equipped with common phrases or pictures.(A1)

Patients with nonfluent aphasias, such as Broca aphasia, exhibit impaired fluency in sentence generation but often retain their singing abilities. Melodic Intonation Therapy (MIT) enhances a patient's fluency by using melody and rhythm. The underlying theory of MIT is to engage the undamaged nondominant hemisphere, which is responsible for intonation while minimizing reliance on the dominant hemisphere. MIT is suitable only for patients with intact auditory comprehension.[29]

Advancements in neuroimaging technology now enable the visualization of activation in the brain's language areas, facilitating further progress in aphasia research and treatment.[13][30] Studies on transcranial stimulation, including transcranial electrical stimulation (TES) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), have yielded promising results.[31] Along with therapy, these approaches have led to improvements in word-finding abilities, functional skills, and overall activity outcomes.[32] Using neuroimaging to identify optimal stimulation sites for transcranial electrical stimulation (TES) is both expensive and time-consuming, making it more applicable in research settings than in clinical practice. In contrast, stimulation of ancillary systems is easier to implement and has shown promising results.[33] Studies on pharmacological therapy have yielded mixed results, often coinciding with the treatment of acute strokes. Drug therapies, including dopaminergic and catecholaminergic agents, may facilitate neural plasticity and recovery but require further research.[34](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Aphasia can present either insidiously or acutely and may result from various conditions, including stroke, brain tumor, brain hemorrhage, TBI, and dementia caused by toxins, infection, or vascular issues, which need to be ruled out.

Other differential diagnoses to consider include:

- Stuttering, which may be associated with real aphasia and sometimes occur due to a dominant hemisphere stroke. Importantly, determining whether stuttering began before or after the acute brain insult is essential.

- Altered mental status, which can result from encephalopathy or delirium.

- Dysphonia

- Dysarthria

- Apraxia of speech

- Cognitive-communication disorder

- Deafness

Prognosis

Aphasia recovery varies based on type, severity, cause, patient motivation, and other factors.[35] The most improvement generally occurs within the first 2 to 3 months after onset, peaking around 6 months, after which recovery rates significantly decline. Broca aphasia typically shows better recovery outcomes than global aphasia, while global aphasia has a more favorable recovery prognosis compared to Wernicke aphasia.[36]

Complications

Patients with aphasia, who were once educated and literate, may struggle to communicate their basic wants and needs. Many patients retain awareness of their deficits, which can lead to frustration and even aggression. They often feel a loss of control over their lives and may experience isolation, resulting in severe depression.[37] In addition, many individuals may face other deficits associated with cerebrovascular accidents, TBIs, or similar conditions, such as loss of mobility, difficulties with activities of daily living, or even becoming bedridden.

Patients with aphasia may experience bowel or bladder incontinence and be unable to communicate when they have urinated or defecated, increasing the risk of infections or pressure ulcers. They may also have pain that goes undertreated. Overall, complications of aphasia often relate to the underlying cause of the condition. In addition, many patients with aphasia also have co-occurring nonlinguistic cognitive deficits, often involving attention and working memory, affecting both verbal and visuospatial domains.[38]

Consultations

Comprehensive care for aphasia typically involves a multidisciplinary team of specialists to address the diverse needs of patients. Consultations may include:

- Physiatrist (physical medicine and rehabilitation)

- Psychiatrist

- Neurologist

- Speech-language pathologist

- Neuropsychologist

Deterrence and Patient Education

Acute stroke is the leading cause of aphasia, and patients should receive education on managing modifiable risk factors to reduce the risk of cerebrovascular events. Hypertension is the most significant modifiable risk factor. Patients are advised to follow various guidelines from organizations such as the American College of Cardiology (ACC) or the Joint National Committee (JNC; JNC-7 and -8 reports) to maintain and keep their blood pressure under control.[39]

Patients with atrial fibrillation should receive anticoagulation based on their CHA2DS2-VASc Score, whereas those with diabetes need to maintain controlled blood sugar levels.[40] Smoking cessation is also crucial. Ultimately, patient education should be tailored to address the specific underlying cause of the aphasia.

Pearls and Other Issues

Understanding that aphasia involves language impairment due to brain injury, not a cognitive deficit, is essential. When communicating with aphasic patients, individuals should speak clearly using simple and short sentences and consider repeating or writing down keywords. Patients should be given ample time to express themselves fully, without interruptions or corrections to their speech.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Aphasia arises from various disease processes and includes multiple syndromes, making misdiagnosis common. A key challenge in diagnosing aphasia is that patients cannot communicate effectively, complicating the history-taking process. This may necessitate gathering history from family members or friends, which can be unreliable or unavailable. Thus, healthcare professionals must be well-versed in recognizing the signs and symptoms of aphasia.

Patients with aphasia often first present to primary care or emergency clinicians, where prompt recognition can aid in diagnosing the underlying cause. For instance, aphasia due to acute stroke may initially be misdiagnosed as delirium. Given the many underlying causes of aphasia, an interprofessional team—including a physiatrist, psychiatrist, neurologist, speech-language pathologist, and neuropsychologist—is essential to address comorbidities and deficits effectively.[28] Interprofessional healthcare team members must understand how to communicate appropriately with aphasic patients to minimize frustration and encourage active participation in care.

The speech-language pathologist plays a central role in identifying the specific aphasia syndrome and developing an individualized rehabilitation plan, often in collaboration with a physiatrist. Depending on the patient’s comorbidities, additional specialists may be needed. Stroke patients may also experience cardiac, pulmonary, renal, or skin-related complications, necessitating care from a cardiologist, pulmonologist, nephrologist, and wound care specialist. Physical and occupational therapists are integral to the healthcare team for managing physical deficits and supporting aphasia treatment. Patients with neurodegenerative diseases will benefit from a neurologist’s expertise, while those with infectious causes require an infectious disease specialist.

Patients with aphasia often experience depression and may need support from healthcare professionals, including neuropsychologists, psychologists, and psychiatrists. Social support is also crucial; family members, friends, and religious leaders require comprehensive education to effectively assist patients in their recovery process.

Specific protocols do not exist for treating patients with aphasia. Treatment and rehabilitation regimens are highly individualized and require a comprehensive interprofessional team of healthcare providers. Proper consultation with specialists and education for family members and friends are essential to optimize patient care and help individuals regain the highest level of independence possible.

Media

References

Yourganov G, Smith KG, Fridriksson J, Rorden C. Predicting aphasia type from brain damage measured with structural MRI. Cortex; a journal devoted to the study of the nervous system and behavior. 2015 Dec:73():203-15. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2015.09.005. Epub 2015 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 26465238]

Nasios G, Dardiotis E, Messinis L. From Broca and Wernicke to the Neuromodulation Era: Insights of Brain Language Networks for Neurorehabilitation. Behavioural neurology. 2019:2019():9894571. doi: 10.1155/2019/9894571. Epub 2019 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 31428210]

Ochfeld E, Newhart M, Molitoris J, Leigh R, Cloutman L, Davis C, Crinion J, Hillis AE. Ischemia in broca area is associated with broca aphasia more reliably in acute than in chronic stroke. Stroke. 2010 Feb:41(2):325-30. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.570374. Epub 2009 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 20044520]

Chang EF, Raygor KP, Berger MS. Contemporary model of language organization: an overview for neurosurgeons. Journal of neurosurgery. 2015 Feb:122(2):250-61. doi: 10.3171/2014.10.JNS132647. Epub 2014 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 25423277]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGrossman M, Irwin DJ. Primary Progressive Aphasia and Stroke Aphasia. Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.). 2018 Jun:24(3, BEHAVIORAL NEUROLOGY AND PSYCHIATRY):745-767. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000618. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29851876]

Hickok G. The cortical organization of speech processing: feedback control and predictive coding the context of a dual-stream model. Journal of communication disorders. 2012 Nov-Dec:45(6):393-402. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2012.06.004. Epub 2012 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 22766458]

Fridriksson J, Yourganov G, Bonilha L, Basilakos A, Den Ouden DB, Rorden C. Revealing the dual streams of speech processing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2016 Dec 27:113(52):15108-15113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614038114. Epub 2016 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 27956600]

Fridriksson J, den Ouden DB, Hillis AE, Hickok G, Rorden C, Basilakos A, Yourganov G, Bonilha L. Anatomy of aphasia revisited. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2018 Mar 1:141(3):848-862. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx363. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29360947]

Kang EK, Sohn HM, Han MK, Paik NJ. Subcortical Aphasia After Stroke. Annals of rehabilitation medicine. 2017 Oct:41(5):725-733. doi: 10.5535/arm.2017.41.5.725. Epub 2017 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 29201810]

Fritsch M, Rangus I, Nolte CH. Thalamic Aphasia: a Review. Current neurology and neuroscience reports. 2022 Dec:22(12):855-865. doi: 10.1007/s11910-022-01242-2. Epub 2022 Nov 16 [PubMed PMID: 36383308]

Satoer D, Koudstaal PJ, Visch-Brink E, van der Giessen RS. Cerebellar-Induced Aphasia After Stroke: Evidence for the "Linguistic Cerebellum". Cerebellum (London, England). 2024 Aug:23(4):1457-1465. doi: 10.1007/s12311-024-01658-1. Epub 2024 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 38244134]

Grönberg A, Henriksson I, Stenman M, Lindgren AG. Incidence of Aphasia in Ischemic Stroke. Neuroepidemiology. 2022:56(3):174-182. doi: 10.1159/000524206. Epub 2022 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 35320798]

Pulvermüller F, Berthier ML. Aphasia therapy on a neuroscience basis. Aphasiology. 2008 Jun:22(6):563-599 [PubMed PMID: 18923644]

Wang R, Wiley C. Confusion vs Broca Aphasia: A Case Report. The Permanente journal. 2020:24():. doi: 10.7812/TPP/19-061. Epub 2019 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 31852049]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHier DB, Yoon WB, Mohr JP, Price TR, Wolf PA. Gender and aphasia in the Stroke Data Bank. Brain and language. 1994 Jul:47(1):155-67 [PubMed PMID: 7922475]

Engelter ST, Gostynski M, Papa S, Frei M, Born C, Ajdacic-Gross V, Gutzwiller F, Lyrer PA. Epidemiology of aphasia attributable to first ischemic stroke: incidence, severity, fluency, etiology, and thrombolysis. Stroke. 2006 Jun:37(6):1379-84 [PubMed PMID: 16690899]

Lahiri D, Dubey S, Sawale VM, Das G, Ray BK, Chatterjee S, Ardila A. Incidence and Symptomatology of Vascular Crossed Aphasia in Bengali. Cognitive and behavioral neurology : official journal of the Society for Behavioral and Cognitive Neurology. 2019 Dec:32(4):256-267. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0000000000000210. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31800486]

Kuljic-Obradovic DC. Subcortical aphasia: three different language disorder syndromes? European journal of neurology. 2003 Jul:10(4):445-8 [PubMed PMID: 12823499]

Deng X, Zhang Y, Xu L, Wang B, Wang S, Wu J, Zhang D, Wang R, Wang J, Zhao J. Comparison of language cortex reorganization patterns between cerebral arteriovenous malformations and gliomas: a functional MRI study. Journal of neurosurgery. 2015 May:122(5):996-1003. doi: 10.3171/2014.12.JNS14629. Epub 2015 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 25658788]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDeWitt I, Rauschecker JP. Wernicke's area revisited: parallel streams and word processing. Brain and language. 2013 Nov:127(2):181-91 [PubMed PMID: 24404576]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCauquil-Michon C, Flamand-Roze C, Denier C. Borderzone strokes and transcortical aphasia. Current neurology and neuroscience reports. 2011 Dec:11(6):570-7. doi: 10.1007/s11910-011-0221-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21904919]

Zhao X, Riccardi N, den Ouden DB, Desai RH, Fridriksson J, Wang Y. Network-based statistics distinguish anomic and Broca aphasia. ArXiv. 2023 Feb 17:(): [PubMed PMID: 36798458]

Riyaz R, Usaid SA, Arram N, Khatroth S, Shah P, Shrestha AB. 'Man-in-the-barrel' syndrome: a case report of bilateral arm paresis following cardiac arrest. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2023 Mar:85(3):435-438. doi: 10.1097/MS9.0000000000000135. Epub 2023 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 36923782]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCong Y, LaCroix AN, Lee J. Clinical efficacy of pre-trained large language models through the lens of aphasia. Scientific reports. 2024 Jul 6:14(1):15573. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-66576-y. Epub 2024 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 38971898]

Jebahi F, Kielar A. The relationship between semantics, phonology, and naming performance in aphasia: a structural equation modeling approach. Cognitive neuropsychology. 2024 May-Jun:41(3-4):113-128. doi: 10.1080/02643294.2024.2373842. Epub 2024 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 38970815]

Medhi G, Parida S, Nicholson P, Senapati SB, Padhy BP, Pereira VM. Mechanical Thrombectomy for Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis: A Case Series and Technical Note. World neurosurgery. 2020 Aug:140():148-161. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.04.220. Epub 2020 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 32389866]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAllida S, Cox KL, Hsieh CF, House A, Hackett ML. Pharmacological, psychological and non-invasive brain stimulation interventions for preventing depression after stroke. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2020 May 11:5(5):CD003689. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003689.pub4. Epub 2020 May 11 [PubMed PMID: 32390167]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBrady MC, Kelly H, Godwin J, Enderby P, Campbell P. Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016 Jun 1:2016(6):CD000425. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000425.pub4. Epub 2016 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 27245310]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSchlaug G, Marchina S, Norton A. From Singing to Speaking: Why Singing May Lead to Recovery of Expressive Language Function in Patients with Broca's Aphasia. Music perception. 2008 Apr 1:25(4):315-323 [PubMed PMID: 21197418]

San Lee J, Yoo S, Park S, Kim HJ, Park KC, Seong JK, Suh MK, Lee J, Jang H, Kim KW, Kim Y, Cho SH, Kim SJ, Kim JP, Jung YH, Kim EJ, Suh YL, Lockhart SN, Seeley WW, Na DL, Seo SW. Differences in neuroimaging features of early- versus late-onset nonfluent/agrammatic primary progressive aphasia. Neurobiology of aging. 2020 Feb:86():92-101. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.10.011. Epub 2019 Nov 26 [PubMed PMID: 31784276]

Naeser MA, Martin PI, Ho M, Treglia E, Kaplan E, Bashir S, Pascual-Leone A. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and aphasia rehabilitation. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2012 Jan:93(1 Suppl):S26-34. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.04.026. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22202188]

Fridriksson J, Rorden C, Elm J, Sen S, George MS, Bonilha L. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation vs Sham Stimulation to Treat Aphasia After Stroke: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA neurology. 2018 Dec 1:75(12):1470-1476. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2287. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30128538]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMeinzer M, Darkow R, Lindenberg R, Flöel A. Electrical stimulation of the motor cortex enhances treatment outcome in post-stroke aphasia. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2016 Apr:139(Pt 4):1152-63. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww002. Epub 2016 Feb 16 [PubMed PMID: 26912641]

Hillis AE. Developments in treating the nonmotor symptoms of stroke. Expert review of neurotherapeutics. 2020 Jun:20(6):567-576. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2020.1763173. Epub 2020 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 32363957]

Berthier ML, García-Casares N, Walsh SF, Nabrozidis A, Ruíz de Mier RJ, Green C, Dávila G, Gutiérrez A, Pulvermüller F. Recovery from post-stroke aphasia: lessons from brain imaging and implications for rehabilitation and biological treatments. Discovery medicine. 2011 Oct:12(65):275-89 [PubMed PMID: 22031666]

Bakheit AM, Shaw S, Carrington S, Griffiths S. The rate and extent of improvement with therapy from the different types of aphasia in the first year after stroke. Clinical rehabilitation. 2007 Oct:21(10):941-9 [PubMed PMID: 17981853]

Kariyawasam PN, Pathirana KD, Hewage DC. Factors associated with health related quality of life of patients with stroke in Sri Lankan context. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2020 May 8:18(1):129. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01388-y. Epub 2020 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 32384894]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKasselimis DS, Simos PG, Economou A, Peppas C, Evdokimidis I, Potagas C. Are memory deficits dependent on the presence of aphasia in left brain damaged patients? Neuropsychologia. 2013 Aug:51(9):1773-6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.06.003. Epub 2013 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 23770384]

Burns J, Persaud-Sharma D, Green D. Beyond JNC 8: implications for evaluation and management of hypertension in underserved populations. Acta cardiologica. 2019 Feb:74(1):1-8. doi: 10.1080/00015385.2018.1435987. Epub 2018 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 29504458]

Chen LQ, Tsiamtsiouris E, Singh H, Rapelje K, Weber J, Dey D, Kosmidou I, Levine J, Cao JJ. Prevalence of Coronary Artery Calcium in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation With and Without Cardiovascular Risk Factors. The American journal of cardiology. 2020 Jun 15:125(12):1765-1769. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.03.018. Epub 2020 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 32336536]