Introduction

Cough is a complex reflex involving coordination between various muscles and neural pathways. Coughing is a protective mechanism for the respiratory system, helping to keep the airways clear of substances that could potentially cause harm or hinder normal breathing. While coughing is generally a healthy response, persistent or chronic coughing can be a symptom of an underlying health issue and may require further investigation and management.

Cough can be divided into 3 types based on the duration of symptoms: acute, subacute, and chronic cough. Chronic cough is a persistent cough that lasts 8 weeks or longer in adults, while subacute cough usually lasts 3 to 8 weeks, and acute cough typically lasts for less than 3 weeks.[1] Chronic cough is a widespread yet underappreciated condition that imposes substantial illness on affected individuals.[2] This activity will focus on chronic cough, a common respiratory symptom for apparent and covert diseases that can significantly impact the quality of life and contribute to a diagnostic dilemma for physicians.[3][4][5] This article will also discuss the etiology, epidemiology, clinical manifestation, evaluation, and management associated with chronic cough.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The most common etiologies of chronic cough involve a range of respiratory and nonrespiratory conditions.

Asthma

In asthma, cough can be the sole symptom, especially in patients with cough-variant asthma.[6] This form of asthma may not present with classic symptoms like wheezing or shortness of breath. Instead, cough may be the predominant or sole manifestation of asthma. This is often referred to as cough-variant asthma. In cough-variant asthma, the airways are hyperresponsive to various triggers, leading to bouts of coughing. The cough can be persistent and may occur during the day or night. Diagnosing cough-variant asthma may involve pulmonary function tests, such as spirometry, to assess how well the lungs function.[7] Other diagnostic measures, such as bronchial provocation tests, may be used to induce and evaluate cough responses.[8]

Nonasthmatic Eosinophilic Bronchitis

NAEB is characterized by eosinophilic inflammation in the airways, similar to asthma. However, it lacks the variable airflow obstruction characteristic of asthma.[9] There is no verifiable airflow limitation on spirometry in NAEB, and methacholine challenge testing (MCT) is usually negative.[10] Chest x-ray results are typically normal. The lack of airflow limitation on spirometry distinguishes NAEB from asthma. In NAEB, sputum examination can reveal eosinophilia in the airways. Unlike asthma, there is usually no mast-cell infiltration in eosinophilic bronchitis.[11] Patients with recurrent episodes of symptomatic NAEB are at an increased risk of developing asthma, and chronic airway obstruction suggests that NAEB may represent an early stage or precursor to asthma in some individuals. This supports the notion that there might be a spectrum of airway diseases, and various factors could influence the progression from eosinophilic bronchitis to asthma.[12]

Chronic Bronchitis

Chronic bronchitis, a type of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), is characterized by persistent cough due to increased mucus production in the airways. Chronic bronchitis is often associated with smoking and remains a significant cause of chronic cough. However, despite the high prevalence of smoking, most smokers with chronic bronchitis do not seek medical attention for their cough. Chronic bronchitis typically accounts for 5% or less of cases of chronic cough.[13] Chronic bronchitis often develops gradually over time. Smokers may adapt to the persistent cough as it becomes a part of their daily life, and they may not consider it a significant enough issue to seek medical attention. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the possibility of neoplasms or lung cancer in individuals with a history of smoking who present with a change in a chronic cough. A cough may become persistent, severe, or accompanied by other concerning symptoms.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Reflux-induced cough can occur through direct and indirect mechanisms. These mechanisms are related to the effects of stomach acid and lead to chronic cough.[14] GERD can directly affect the airway when gastric acid flows back into the esophagus and irritates the proximal esophagus and the laryngopharyngeal areas. This irritation triggers a cough reflex as a protective response to clear the airways. The gastric content can also indirectly cause chronic cough by stimulating the distal part of the esophagus, resulting in irritation to the vagus nerve and triggering reflexes like coughing. In some cases, reflux-induced cough may occur without typical symptoms of acid reflux, such as heartburn. This is known as silent reflux. Most cases of reflux-induced cough are silent reflux, making it challenging to diagnose based on symptoms alone.[15][16]

Upper Airway Cough Syndrome

Formerly known as postnasal drip syndrome, UACS is a significant contributor to chronic cough, comparable to other major causes, such as asthma and gastroesophageal reflux. The mechanisms underlying cough in individuals with nasal and sinus diseases involve several factors, including postnasal drip, direct irritation of nasal mucosa, inflammation in the upper and lower airways, and sensitization of the cough reflex. The cough observed in UACS patients is suggested to arise from the hypersensitivity of sensory nerves in the upper and lower airways or a combination of these factors.[17]

Medications

Cough is an adverse effect of some medications, particularly angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.[18] ACE inhibitors are prescribed to treat hypertension and heart failure. Thirty percent of patients develop dry cough symptoms usually a few hours after taking the medication but can be delayed for weeks or months after starting the drug.[19] The exact mechanism behind ACE inhibitor-induced cough is not entirely clear, but it is believed to be related to the increased sensitivity of the cough reflex. One proposed mechanism involves the accumulation of bradykinin, a substance usually broken down by ACE. When bradykinin levels rise due to ACE inhibition, this can stimulate afferent C-fibers in the airway, which leads to cough.[20] Medications that increase gastroesophageal reflux (GER), such as calcium channel blockers and bisphosphonates, can theoretically exacerbate preexisting reflux and cough. Study results revealed that the cough rate with calcium channel antagonists was similar to losartan but significantly less than that with ACE inhibitors.[21] Finally, prostanoid eye drops, including latanoprost, are commonly used to treat glaucoma by reducing intraocular pressure. There have been reports of adverse effects related to these eye drops, specifically, irritation of the pharynx.[22]

Bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis is characterized by abnormal, irreversible dilation of the bronchi (the airways leading to the lungs). Bronchiectasis accounts for <2% of patients with chronic cough but can be seen in up to 4% of those with excessive sputum production.[23] The cardinal symptom of bronchiectasis is a chronic productive cough; patients with this condition typically experience a persistent cough that produces sputum or phlegm. The dilation and damage to the airways make it difficult for the lungs to effectively clear mucus, leading to chronic cough and, often, mucus production. While some individuals with this condition may experience only a dry cough, most tend to produce chronic sputum that is mucopurulent (containing mucus and pus). During exacerbations, the sputum may become frankly purulent. There are reports of overlap between bronchiectasis and other airway diseases associated with increased lung inflammation and frequent exacerbations, which precipitate chronic cough.[24]

Postinfection

Respiratory tract pathogens are a common cause of cough. Although cough typically resolves within days, cough reflex hypersensitivity might last for several weeks or even longer, perhaps related to inflammation of the vagal nerves. Twenty-five percent of patients with chronic cough report a postinfectious etiology due to upper respiratory infection.[25] During outbreaks of respiratory infections caused by pathogens like Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Bordetella pertussis (whooping cough), and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19), there tends to be an increase in cases of cough.[26][27][28] Exposure to various allergic or non-allergic irritants can lead to local tissue inflammation. This inflammation can affect the vagal nerves or their central pathways, contributing to the development of cough hypersensitivity.[29] Inflammation or irritation of the vagal nerves during the infection can contribute to prolonged cough hypersensitivity. The vagus nerve plays a central role in regulating the cough reflex, and any disturbance in its function can lead to persistent coughing.[30] Individual responses to infections must be followed, and the subsequent cough reflex can vary. Some individuals may experience heightened sensitivity and a lingering cough, while others recover without complications.[31]

Neoplasm

Tumors in the respiratory system can irritate airways and lead to a persistent cough. Cough is a common symptom among patients with lung cancer (57%) and is often a presenting symptom that can significantly impact the patient's quality of life.[32] Half of patients reported the need for treatment due to the severity of their cough, with 23% experiencing associated pain.[33] The prevalence of cough in lung cancer can be attributed to various factors. Tumors in the lung can irritate or obstruct airways, triggering the cough reflex. Cancer-related inflammation, infections, or the body's response to the presence of cancer cells can contribute to coughing.

Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD)

Cough is a common symptom associated with ILD and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). The etiology of coughing in IPF remains poorly understood.[34] Eighty percent of patients with IPF may experience a chronic cough. Therefore, it is crucial to identify chronic cough and assess its severity and impact on an individual's quality of life.[35] When patients have a persistent cough, it's crucial to investigate alternative causes before assuming it's due to interstitial lung disease (ILD). Common causes like upper airway cough syndrome (UACS), asthma, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) should be considered. Due to overlapping symptoms, a diagnosis of ILD should only be made after ruling out other potential causes. Several validated tools, such as 24-hour cough monitoring and health-related quality of life questionnaires, assess cough in IPF. These tools help objectively measure the frequency and severity of cough and understand its impact on the patient's quality of life.[36] The mechanism of cough in ILD is complex and may involve multiple factors. Cough in IPF can be attributed to mechanical distortion associated with lung parenchymal fibrosis. The scarring and lung fibrosis may lead to irritation and cough reflexes. This heightened sensitivity can contribute to the persistent cough seen in these patients. Additionally, gastroesophageal reflux is another potential contributor to cough in IPF. The backflow of stomach contents into the esophagus can irritate the airways and trigger a cough. This is particularly relevant because GERD is a common comorbidity in patients with IPF.[37] Finally, airway inflammation is also considered a potential mechanism for cough in IPF. Inflammation in the airways can lead to increased irritability and coughing.[38]

Idiopathic

A chronic cough with an unknown cause that does not respond to empirical treatment and is refractory can be considered idiopathic. The association of idiopathic chronic cough with organ-specific autoimmune disease raises the possibility that it may be caused by lymphocyte homing from the primary site of autoimmune inflammation or due to an autoimmune process in the lung.[39]

Epidemiology

Chronic cough has a global prevalence of 3% to 18% in the general adult population and is affected by several factors, such as smoking and age.[40][41] Eighteen percent of adults in the United States who smoke have chronic coughs.[42] The prevalence is variable, however, based on the location of the population studied.[43] Chronic cough was significantly more frequent in Europe and America than in Asia and Africa. However, the geographic variation is not genetic or ethnically related.[44][45] The regional variation in chronic cough prevalence may be attributed to environmental factors, particularly urbanization in Western countries, which can lead to increased inhalational exposure to irritants.[2]

The findings from the KNHANES 2010–2012 study indicate that the prevalence of chronic cough increases significantly with age. The odds ratio (OR) of 2.20 and 95% confidence interval of 1.53 to 3.16 suggests a substantial increase in the likelihood of chronic cough among individuals 65 or older compared to those aged 18 to 39.[46] This finding aligns with the general trend observed in various studies, where chronic cough becomes more prevalent in older age groups.[47] The cumulative effects of environmental exposures over time may also play a role. One study by Dicpinigaitis et al assessed ethnic and sex differences in cough reflex sensitivity and found no significant ethnic differences in cough reflex sensitivity among 3 distinct ethnic groups: White, Indian, and Chinese. This suggests that the variation in the prevalence of chronic cough among different races may not be directly attributed to differences in cough reflex sensitivity.[45]

In addition to age and smoking, the factors that contribute to the increased prevalence of chronic cough include obesity, atopy, asthma, COPD, GERD, ACE inhibitors, and sleep-disordered breathing. Other factors, such as air pollution and air quality, do not significantly affect the prevalence of chronic cough, and study results have been inconclusive, except for metal exposure.[47]

Pathophysiology

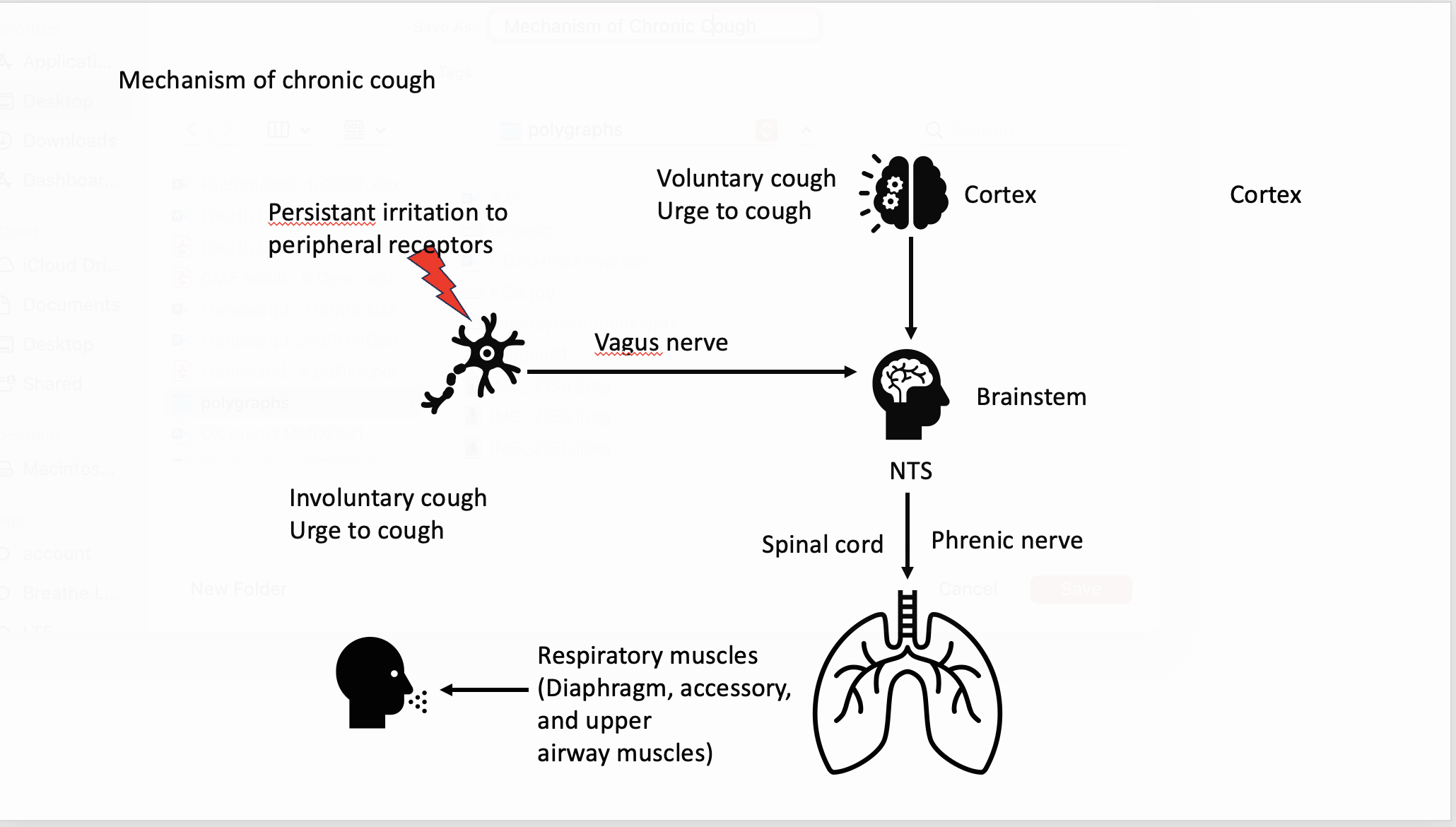

There are 3 phases of a cough: 1) Inhalation, which generates enough volume for an effective cough; 2) Compression, with pressure against a closed larynx by the contraction of the chest wall, diaphragm, and abdominal muscles; 3) Expiration, which begins when the glottis opens, resulting in high airflow. A cough can be a voluntary or involuntary act. A voluntary cough is manifested by cough inhibition or initiation. The central projections of vagal afferents, specifically those involved in the cough reflex, terminate in the brainstem (see Image. Cough and the Nervous System).[17]

The cough reflex is not a fixed, unchanging response but rather a dynamic process that can be influenced by various inputs and stimuli, a phenomenon called "cough plasticity." Vagal afferent fibers, part of the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X), play a crucial role in sensing and transmitting information from the airways to the brainstem, particularly the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS). These afferent fibers can be classified into subtypes based on how they respond to various stimuli.[48]

The initiation and control of cough involve a complex interplay of neural pathways, including the activation of vagal afferents and central processing in the NTS. The central projections of vagal afferents, specifically those involved in the cough reflex, terminate in the brainstem. The NTS is a critical nucleus in the medulla oblongata, where these afferents synapse with second-order neurons. The NTS processes sensory information from various organs, including the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts.[49] Afferent signals move down the phrenic and spinal motor nerves to the expiratory muscles, producing the cough. A chronic cough may also be brought about by abnormalities of the cough reflex and sensitization of its afferent and central components with exaggerated cough reflex sensitivity to stimuli that generally do not cause a cough (cough hypersensitivity syndrome).[50]

History and Physical

The initial evaluation of a patient with a chronic cough should include a focused history and physical examination. The full assessment should include documentation of its characteristics, such as the duration, its productive or nonproductive nature, and any accompanying symptoms, such as rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, sneezing, fever, hemoptysis, dyspnea, weight loss, dysphonia, dysphagia, and whooping cough.[51]

Furthermore, it is vital to inquire about any prior occurrences of cough and to gather information regarding the patient's or their family's history of allergic rhinitis. Additionally, a history of tobacco smoking, vaping (eg, electronic cigarettes), occupational exposure, and travel-related exposure should be obtained, as these not only serve as irritants but also increase the likelihood of developing chronic bronchitis and lung cancer.[52]

The patient's medical history includes questioning regarding the use of medication that may contribute to a chronic cough, such as ACE inhibitors. Among adults, the most common causes of chronic cough include asthma, UACS, and GERD. Therefore, it is essential to screen for symptoms that suggest these disorders.

Silent UACS is a condition in which patients experience a cough as the sole symptom, often due to nasopharyngeal conditions such as allergic rhinitis and rhinosinusitis.[1] This may result in a subtle sensation of irritation in the back of the throat and upper airways secondary to postnasal drip. Examination of the throat may reveal signs of pharyngitis and a "cobblestone" appearance. Sometimes, these conditions may be asymptomatic, with cough being the only presenting symptom. Due to the chronicity of the disease, patients may become desensitized to other symptoms over time, making the cough seem more bothersome in comparison. The diagnosis of silent UACS can only be reliably made after patients demonstrate significant improvement with prescribed treatment directed at the identified features in their history, physical examination, or laboratory test results.[53]

Clinicians must promptly identify any life-threatening signs and consider the presence of fevers, night sweats, or weight loss that suggests chronic infections (eg, tuberculosis, lung abscess), cancer (pulmonary, bronchial, or laryngeal), or rheumatic diseases. The presence of purulent sputum warrants further evaluation. Hemoptysis may indicate infections, cancer, rheumatic diseases, heart failure, or foreign body inhalation.

Associated dyspnea can indicate airway obstruction (laryngeal, tracheal, bronchial, bronchiolar) or lung parenchymal disease. Other features can aid in narrowing down the cause of chronic cough. These include specific triggers, associated hoarseness, focal abnormalities on examination, and waxing and waning versus progressively worsening severity.

Evaluation

Assessing a persistent cough necessitates an organized methodology and a personalized strategy.[6]

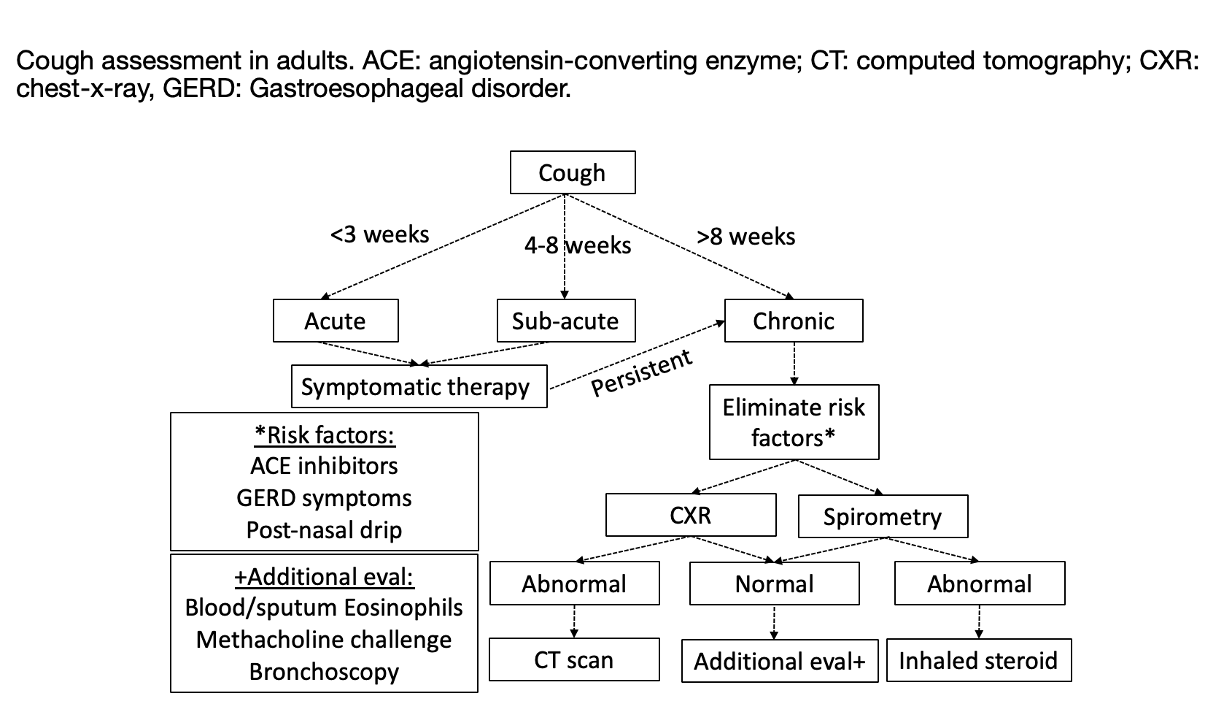

The initial assessment of a chronic cough typically involves a chest radiograph and pulmonary function tests (PFTs). A chest x-ray is generally recommended for most adults with a cough that has persisted for over 8 weeks (see Image. Assessment of Cough in Adults). There may be exceptions for individuals in whom the suspected diagnosis is asthma or UACS, who may receive empiric therapy instead.[54] Chest CT scans should not be routinely performed for patients with normal chest examinations and radiographs. Still, they may be necessary for further evaluation of abnormalities detected on the radiograph or for diagnosing conditions that may not be visible on plain radiography, such as bronchiectasis.[55] The threshold for obtaining a chest CT for patients with a chronic cough may be lower for those at increased risk for lung cancer, such as individuals with a history of heavy smoking.

PFTs, including spirometry before and after administering a bronchodilator, may also be used to evaluate the possibility of asthma or COPD. When PFT results are normal, some professionals advocate further investigation of bronchial hyperresponsiveness using either methacholine or histamine inhalational challenge. However, the utility of these modalities in diagnosis is still debated.

The present guidelines offer recommendations for utilizing noninvasive techniques for measuring airway inflammation when evaluating and managing cough associated with asthma or NAEB, based on a thorough review of the pertinent literature.[56] Evidence for ongoing airway eosinophilic inflammation can be sought by performing differential cell counts on samples from sputum induction or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). In such cases, elevated eosinophils (>3%) in the airways without bronchial hyperresponsiveness would suggest eosinophilic bronchitis, reported in up to 13% of patients attending cough clinics.[57] The usefulness of fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) or blood eosinophils in diagnosing or predicting treatment response in patients with chronic cough has yet to be fully assessed in a clinical setting. Despite this, there is currently insufficient high-quality evidence available. Controlled trials with a placebo group are necessary to determine efficacy, and consensus regarding the threshold levels for patients with chronic cough is needed.[58]

Idiopathic chronic cough lasts longer than 3 weeks without an apparent cause despite negative treatment trials. Elevated lymphocyte levels in the BAL fluid sometimes accompany this condition.[39]

Treatment / Management

Patients taking an ACE inhibitor may benefit from a trial of switching to another drug class. Sequential empirical therapy is advised before embarking on an extensive workup. If UACS is suspected, a trial of nasal saline rinses, a first-generation antihistamine, and nasal steroids is recommended.

For adult patients with chronic cough due to chronic bronchitis, there is insufficient evidence to recommend routine pharmacologic treatments (eg, antibiotics, bronchodilators, mucolytics) to relieve cough.[13]

Empiric therapy for GERD involves dietary modifications, lifestyle changes, antacids, and proton pump inhibitors for 3 months, which should be prescribed before considering 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring. If sputum or BAL testing reveals >3% eosinophils, inhaled steroids can be used to treat NAEB.

Some patients, particularly those referred to specialized clinics, may exhibit multiple underlying causes for their persistent cough. In such instances, it is essential to address all contributing factors simultaneously to resolve the cough completely.

The management of chronic cough caused by asthma is similar to the initial treatment of asthma using a stepwise approach.[8] Like in asthma, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are the mainstay of therapy for cough due to asthma.[56] In adult patients with chronic cough due to asthma as a sole symptom (cough-variant asthma), we suggest inhaled ICS as a first-line treatment. Increasing the ICS dose is recommended if the response is incomplete in those with cough-variant asthma. This is also the recommendation if cough is the remaining isolated symptom following treatment with ICS. A therapeutic trial of a leukotriene inhibitor can also be considered. Beta-agonists can also be considered in combination with ICS.[56]

In idiopathic chronic cough, several treatments may be considered, including opiates and nonopioid pharmacological treatments. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) was conducted to assess the efficacy of low-dose, slow-release morphine (5 to 10 mg twice daily) in adult individuals with persistent, treatment-resistant idiopathic chronic cough, a sample of patients was evaluated and was found to be more effective in reducing cough severity than placebo.[59] The utility of nonopioid medications such as gabapentin or pregabalin was also assessed as a treatment for idiopathic cough. In a study conducted to evaluate the efficacy of gabapentin therapy (maximum daily dose of 1800 mg) in adults with persistent, refractory cough, it was found that there were significant improvements in quality of life compared to placebo.[60] Another study looked at the combination of pregabalin therapy (300 mg daily) with speech pathology therapy and found this approach effective in improving cough-specific quality of life in adult patients with chronic refractory cough.[61](A1)

Below are detailed recommended therapies for different types of chronic cough in adults based on the most recent guidelines.[6]

(A1)| Cause of chronic cough | Treatment |

| Asthma |

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are the first-line therapy (conditional recommendation, low-quality evidence). Empirical trials suggest that higher doses of ICS may be more effective than low-to-moderate doses. However, the trial should be discontinued if no response is observed within 2 to 4 weeks. Beta-agonists may be considered in combination with ICS.[6] |

| NAEB | ICS are the preferred initial treatment option (conditional recommendation, low-quality evidence). If the patient does not show adequate improvement, the dose should be increased for 2 to 4 weeks, and a leukotriene inhibitor should be considered as additional therapy.[56] The empirical trial should be discontinued if no response is elicited within 2 to 4 weeks. |

| GERD | The benefits of anti-acid (H2-antagonists) or proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for cough relief in patients without acid reflux are limited. The improvement is only mild in those with acid reflux (conditional recommendation, low-quality evidence).[62][6] In patients with chronic bronchitis and a persistent cough, a 1-month trial of macrolides may be considered while adhering to local antimicrobial stewardship guidelines (conditional recommendation, low-quality evidence).[63] |

| UACS | Initial treatments for allergic UACS involve nasal corticosteroids or antihistamines. For patients with UACS unrelated to allergies, such as postinfection, the older generation of antihistamines should be considered (weak recommendations, low quality).[64] |

| ILD |

Individuals with sarcoidosis-related cough may benefit from a treatment plan involving oral corticosteroids followed by ICS.[65] However, corticosteroids must be individualized in patients with cough secondary to IPF (low evidence, weak recommendations).[66] |

| Idiopathic | Recommended trial of low-dose, slow-release morphine (5 to 10 mg twice daily) (strong recommendation, moderate-quality evidence).[59]

A trial of gabapentin or pregabalin is also recommended for individuals who seek to avoid or are unable to tolerate medications that contain opioids (conditional recommendation, low-quality evidence).[60] Gabapentin is usually initiated with a daily dose of 300 mg, gradually increasing until cough relief, adverse effects, or a maximum dose of 1800 mg per day in 2 doses is reached.[67] |

Nonpharmacological treatments in adult patients with chronic cough (eg, physiotherapy, speech and language therapy) are recommended.[54] Two RCTs have been undertaken to evaluate the efficacy of cough control therapy in adult patients with chronic refractory cough. The first study by Vertigan et al revealed that a 2-month intervention led to a statistically significant reduction in subjective cough scores compared to placebo treatment.[68] The second study by Chamberlain Mitchell et al demonstrated improvements in cough-specific quality of life and objective cough frequency in the intervention group compared to placebo.[69] The benefits in the intervention group were sustained for up to 3 months. Neither study reported any adverse effects.(A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of chronic cough includes the following conditions:

- Bronchiolitis

- Bronchogenic carcinoma

- Chronic aspiration

- Congestive heart failure

- Foreign body aspiration

- Neuromuscular disorders

- Psychogenic cough

Prognosis

Cough is a distinct and independent factor that can serve as an indicator of disease progression. The prognostic implications of cough in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) are significant. A study of 242 IPF patients revealed that the presence of cough was an independent predictor of disease progression, regardless of the severity of the disease. Furthermore, cough was more prevalent in patients with advanced pulmonary fibrosis. Nevertheless, it is crucial to differentiate whether the cough results from the underlying inflammation or fibrosis or is due to a comorbidity when assessing cough in patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD).[70]

A recent study revealed that many individuals diagnosed with chronic cough continued to experience persistent coughing for at least 5 years.[71] This finding was somewhat more optimistic than a prior study on the same subject, which reported that 60% of patients experienced worsening or unchanged cough symptoms at a 7-year follow-up.[72] The disparity in the results can be attributed to differences in the patient populations studied. The earlier investigation was limited to patients with unexplained chronic cough, whereas the recent study enrolled individuals with various cough-related disorders and idiopathic cough. Thus, the latter study may provide a more accurate representation of the general chronic cough patient population. Notably, the prevalence of autoimmune diseases was high in the more recent group, a characteristic commonly observed in patients with idiopathic chronic cough.[73] Among the study participants, most asthma and chronic rhinitis patients were effectively managed with local corticosteroid preparations or antihistamines. However, most reflux disease patients did not receive treatment with proton pump inhibitors, an ineffective regimen for reflux-associated cough.[16] Consequently, the study population likely reflects the real-life medication regimens of patients. The study further identified obesity as a significant predictor of continued cough-related quality of life impairment. Indeed, subjects who met the current criteria for obesity were found to be at a higher risk for ongoing cough-related distress.

Complications

Chronic cough, when left unaddressed, can lead to a range of complications that significantly impact an individual's quality of life. Prolonged coughing episodes may result in physical exhaustion, disturbed sleep patterns, and increased stress, ultimately affecting one's overall well-being. Persistent coughing can also contribute to the development of musculoskeletal issues, such as chest pain and soreness in the abdominal muscles. Socially, chronic cough may lead to embarrassment and social isolation due to its disruptive nature in public settings. Repeated irritation of the airways can exacerbate underlying respiratory conditions, potentially leading to complications such as bronchitis or pneumonia. Long-term coughing can also contribute to stress urinary incontinence, particularly in women. Therefore, addressing chronic cough promptly through medical intervention and lifestyle modifications is crucial to prevent these complications and improve the overall health and daily functioning of individuals affected by this persistent condition.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence and prevention strategies for chronic cough aim to mitigate the underlying causes and reduce the risk of persistent respiratory symptoms. Emphasizing lifestyle modifications, such as smoking cessation and avoidance of environmental pollutants, forms a crucial aspect of deterrence. Educational campaigns can play a pivotal role in raising awareness about the adverse health effects of smoking and the importance of maintaining a clean indoor environment. Regular check-ups with healthcare professionals facilitate early detection and intervention, preventing acute respiratory conditions from progressing into chronic cough. Immunization against preventable respiratory infections is another key preventive measure. Additionally, implementing workplace policies that reduce exposure to occupational hazards and airborne irritants can significantly deter chronic cough. By fostering a comprehensive approach that combines individual responsibility, public education, and healthcare interventions, society can work towards reducing the burden of chronic cough on both individual health and healthcare systems.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Chronic cough necessitates an interprofessional team due to its multitude of potential causes. Primary care clinicians and nurse practitioners must consistently consider the possibility of malignancy when evaluating patients presenting with a persistent cough. In cases where the cough persists, referring the patient for appropriate diagnostic evaluations is highly advisable. The prognosis for chronic cough is contingent upon the underlying cause.[74][75][76][77]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Irwin RS, French CL, Chang AB, Altman KW, CHEST Expert Cough Panel*. Classification of Cough as a Symptom in Adults and Management Algorithms: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2018 Jan:153(1):196-209. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.10.016. Epub 2017 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 29080708]

Song WJ, Morice AH, Kim MH, Lee SE, Jo EJ, Lee SM, Han JW, Kim TH, Kim SH, Jang HC, Kim KW, Cho SH, Min KU, Chang YS. Cough in the elderly population: relationships with multiple comorbidity. PloS one. 2013:8(10):e78081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078081. Epub 2013 Oct 21 [PubMed PMID: 24205100]

Morice AH, McGarvey L, Pavord I, British Thoracic Society Cough Guideline Group. Recommendations for the management of cough in adults. Thorax. 2006 Sep:61 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i1-24 [PubMed PMID: 16936230]

Ptak K, Cichocka-Jarosz E, Kwinta P. [Chronic cough in children]. Developmental period medicine. 2018:22(4):329-340 [PubMed PMID: 30636230]

Koehler U, Hildebrandt O, Walliczek-Dworschak U, Nikolaizik W, Weissflog A, Urban C, Kerzel S, Sohrabi K, Groß V. [Chronic cough - New diagnostic options for evaluation?]. Laryngo- rhino- otologie. 2019 Jan:98(1):14-20. doi: 10.1055/a-0790-0777. Epub 2019 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 30620964]

Morice AH, Millqvist E, Bieksiene K, Birring SS, Dicpinigaitis P, Domingo Ribas C, Hilton Boon M, Kantar A, Lai K, McGarvey L, Rigau D, Satia I, Smith J, Song WJ, Tonia T, van den Berg JWK, van Manen MJG, Zacharasiewicz A. ERS guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in adults and children. The European respiratory journal. 2020 Jan:55(1):. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01136-2019. Epub 2020 Jan 2 [PubMed PMID: 31515408]

Hao H, Pan Y, Xu Z, Xu Z, Bao W, Xue Y, Lv C, Lin J, Zhang Y, Zhang M. Prediction of bronchodilation test in adults with chronic cough suspected of cough variant asthma. Frontiers in medicine. 2022:9():987887. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.987887. Epub 2022 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 36569143]

Hashmi MF, Cataletto ME. Asthma. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613651]

Diab N, Patel M, O'Byrne P, Satia I. Narrative Review of the Mechanisms and Treatment of Cough in Asthma, Cough Variant Asthma, and Non-asthmatic Eosinophilic Bronchitis. Lung. 2022 Dec:200(6):707-716. doi: 10.1007/s00408-022-00575-6. Epub 2022 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 36227349]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLai K, Liu B, Xu D, Han L, Lin L, Xi Y, Wang F, Chen R, Luo W, Chen Q, Zhong N. Will nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis develop into chronic airway obstruction?: a prospective, observational study. Chest. 2015 Oct:148(4):887-894. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2351. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25905627]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBrightling CE, Symon FA, Birring SS, Bradding P, Wardlaw AJ, Pavord ID. Comparison of airway immunopathology of eosinophilic bronchitis and asthma. Thorax. 2003 Jun:58(6):528-32 [PubMed PMID: 12775868]

Park SW, Lee YM, Jang AS, Lee JH, Hwangbo Y, Kim DJ, Park CS. Development of chronic airway obstruction in patients with eosinophilic bronchitis: a prospective follow-up study. Chest. 2004 Jun:125(6):1998-2004 [PubMed PMID: 15189914]

Malesker MA, Callahan-Lyon P, Madison JM, Ireland B, Irwin RS, CHEST Expert Cough Panel. Chronic Cough Due to Stable Chronic Bronchitis: CHEST Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2020 Aug:158(2):705-718. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.02.015. Epub 2020 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 32105719]

Irwin RS. Chronic cough due to gastroesophageal reflux disease: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006 Jan:129(1 Suppl):80S-94S. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.80S. Epub [PubMed PMID: 16428697]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWang S, Wen S, Bai X, Zhang M, Zhu Y, Wu M, Lu L, Shi C, Yu L, Xu X. Diagnostic value of reflux episodes in gastroesophageal reflux-induced chronic cough: a novel predictive indicator. Therapeutic advances in chronic disease. 2022:13():20406223221117455. doi: 10.1177/20406223221117455. Epub 2022 Aug 17 [PubMed PMID: 36003286]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKahrilas PJ, Altman KW, Chang AB, Field SK, Harding SM, Lane AP, Lim K, McGarvey L, Smith J, Irwin RS, CHEST Expert Cough Panel. Chronic Cough Due to Gastroesophageal Reflux in Adults: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2016 Dec:150(6):1341-1360. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.1458. Epub 2016 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 27614002]

Lucanska M, Hajtman A, Calkovsky V, Kunc P, Pecova R. Upper Airway Cough Syndrome in Pathogenesis of Chronic Cough. Physiological research. 2020 Mar 27:69(Suppl 1):S35-S42 [PubMed PMID: 32228010]

Woo KS, Nicholls MG. High prevalence of persistent cough with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in Chinese. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 1995 Aug:40(2):141-4 [PubMed PMID: 8562296]

Berkin KE, Ball SG. Cough and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition. British medical journal (Clinical research ed.). 1988 May 7:296(6632):1279 [PubMed PMID: 3133049]

Borghi C, Cicero AF, Agnoletti D, Fiorini G. Pathophysiology of cough with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: How to explain within-class differences? European journal of internal medicine. 2023 Apr:110():10-15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2023.01.005. Epub 2023 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 36628825]

Samizo K, Kawabe E, Hinotsu S, Sato T, Kageyama S, Hamada C, Ohashi Y, Kubota K. Comparison of losartan with ACE inhibitors and dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonists: a pilot study of prescription-event monitoring in Japan. Drug safety. 2002:25(11):811-21 [PubMed PMID: 12222991]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFahim A, Morice AH. Heightened cough sensitivity secondary to latanoprost. Chest. 2009 Nov:136(5):1406-1407. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0070. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19892680]

Rosen MJ. Chronic cough due to bronchiectasis: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006 Jan:129(1 Suppl):122S-131S. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.122S. Epub [PubMed PMID: 16428701]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePolverino E, Dimakou K, Hurst J, Martinez-Garcia MA, Miravitlles M, Paggiaro P, Shteinberg M, Aliberti S, Chalmers JD. The overlap between bronchiectasis and chronic airway diseases: state of the art and future directions. The European respiratory journal. 2018 Sep:52(3):. pii: 1800328. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00328-2018. Epub 2018 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 30049739]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePoe RH, Harder RV, Israel RH, Kallay MC. Chronic persistent cough. Experience in diagnosis and outcome using an anatomic diagnostic protocol. Chest. 1989 Apr:95(4):723-8 [PubMed PMID: 2924600]

Davis SF, Sutter RW, Strebel PM, Orton C, Alexander V, Sanden GN, Cassell GH, Thacker WL, Cochi SL. Concurrent outbreaks of pertussis and Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection: clinical and epidemiological characteristics of illnesses manifested by cough. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 1995 Mar:20(3):621-8 [PubMed PMID: 7756486]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYaari E, Yafe-Zimerman Y, Schwartz SB, Slater PE, Shvartzman P, Andoren N, Branski D, Kerem E. Clinical manifestations of Bordetella pertussis infection in immunized children and young adults. Chest. 1999 May:115(5):1254-8 [PubMed PMID: 10334136]

Song WJ, Hui CKM, Hull JH, Birring SS, McGarvey L, Mazzone SB, Chung KF. Confronting COVID-19-associated cough and the post-COVID syndrome: role of viral neurotropism, neuroinflammation, and neuroimmune responses. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine. 2021 May:9(5):533-544. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00125-9. Epub 2021 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 33857435]

Chung KF, McGarvey L, Mazzone S. Chronic cough and cough hypersensitivity syndrome. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine. 2016 Dec:4(12):934-935. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30373-3. Epub 2016 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 27890496]

Mazzone SB, Satia I, McGarvey L, Song WJ, Chung KF. Chronic cough and cough hypersensitivity: from mechanistic insights to novel antitussives. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine. 2022 Dec:10(12):1113-1115. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00404-0. Epub 2022 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 36372083]

Chung KF, McGarvey L, Mazzone SB. Chronic cough as a neuropathic disorder. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine. 2013 Jul:1(5):414-22. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70043-2. Epub 2013 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 24429206]

Iyer S, Roughley A, Rider A, Taylor-Stokes G. The symptom burden of non-small cell lung cancer in the USA: a real-world cross-sectional study. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2014 Jan:22(1):181-7. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1959-4. Epub 2013 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 24026981]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMolassiotis A, Smith JA, Mazzone P, Blackhall F, Irwin RS, CHEST Expert Cough Panel. Symptomatic Treatment of Cough Among Adult Patients With Lung Cancer: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2017 Apr:151(4):861-874. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.12.028. Epub 2017 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 28108179]

Bargagli E, Di Masi M, Perruzza M, Vietri L, Bergantini L, Torricelli E, Biadene G, Fontana G, Lavorini F. The pathogenetic mechanisms of cough in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Internal and emergency medicine. 2019 Jan:14(1):39-43. doi: 10.1007/s11739-018-1960-5. Epub 2018 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 30269188]

Key AL, Holt K, Hamilton A, Smith JA, Earis JE. Objective cough frequency in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Cough (London, England). 2010 Jun 21:6():4. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-6-4. Epub 2010 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 20565979]

Birring SS, Kavanagh JE, Irwin RS, Keogh KA, Lim KG, Ryu JH, Collaborators. Treatment of Interstitial Lung Disease Associated Cough: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2018 Oct:154(4):904-917. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.06.038. Epub 2018 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 30036496]

Tobin RW, Pope CE 2nd, Pellegrini CA, Emond MJ, Sillery J, Raghu G. Increased prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1998 Dec:158(6):1804-8 [PubMed PMID: 9847271]

Birring SS, Parker D, McKenna S, Hargadon B, Brightling CE, Pavord ID, Bradding P. Sputum eosinophilia in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Inflammation research : official journal of the European Histamine Research Society ... [et al.]. 2005 Feb:54(2):51-6 [PubMed PMID: 15750711]

Birring SS, Brightling CE, Symon FA, Barlow SG, Wardlaw AJ, Pavord ID. Idiopathic chronic cough: association with organ specific autoimmune disease and bronchoalveolar lymphocytosis. Thorax. 2003 Dec:58(12):1066-70 [PubMed PMID: 14645977]

Chung KF, McGarvey L, Song WJ, Chang AB, Lai K, Canning BJ, Birring SS, Smith JA, Mazzone SB. Cough hypersensitivity and chronic cough. Nature reviews. Disease primers. 2022 Jun 30:8(1):45. doi: 10.1038/s41572-022-00370-w. Epub 2022 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 35773287]

Maio S, Baldacci S, Carrozzi L, Pistelli F, Simoni M, Angino A, La Grutta S, Muggeo V, Viegi G. 18-yr cumulative incidence of respiratory/allergic symptoms/diseases and risk factors in the Pisa epidemiological study. Respiratory medicine. 2019 Oct-Nov:158():33-41. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2019.09.013. Epub 2019 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 31585374]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBarbee RA, Halonen M, Kaltenborn WT, Burrows B. A longitudinal study of respiratory symptoms in a community population sample. Correlations with smoking, allergen skin-test reactivity, and serum IgE. Chest. 1991 Jan:99(1):20-6 [PubMed PMID: 1984955]

Janson C, Anto J, Burney P, Chinn S, de Marco R, Heinrich J, Jarvis D, Kuenzli N, Leynaert B, Luczynska C, Neukirch F, Svanes C, Sunyer J, Wjst M, European Community Respiratory Health Survey II. The European Community Respiratory Health Survey: what are the main results so far? European Community Respiratory Health Survey II. The European respiratory journal. 2001 Sep:18(3):598-611 [PubMed PMID: 11589359]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSong WJ, Chang YS, Faruqi S, Kim JY, Kang MG, Kim S, Jo EJ, Kim MH, Plevkova J, Park HW, Cho SH, Morice AH. The global epidemiology of chronic cough in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The European respiratory journal. 2015 May:45(5):1479-81. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00218714. Epub 2015 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 25657027]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDicpinigaitis PV, Allusson VR, Baldanti A, Nalamati JR. Ethnic and gender differences in cough reflex sensitivity. Respiration; international review of thoracic diseases. 2001:68(5):480-2 [PubMed PMID: 11694809]

Kang MG, Song WJ, Kim HJ, Won HK, Sohn KH, Kang SY, Jo EJ, Kim MH, Kim SH, Kim SH, Park HW, Chang YS, Lee BJ, Morice AH, Cho SH. Point prevalence and epidemiological characteristics of chronic cough in the general adult population: The Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010-2012. Medicine. 2017 Mar:96(13):e6486. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006486. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28353590]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYang X, Chung KF, Huang K. Worldwide prevalence, risk factors and burden of chronic cough in the general population: a narrative review. Journal of thoracic disease. 2023 Apr 28:15(4):2300-2313. doi: 10.21037/jtd-22-1435. Epub 2023 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 37197554]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNarula M, McGovern AE, Yang SK, Farrell MJ, Mazzone SB. Afferent neural pathways mediating cough in animals and humans. Journal of thoracic disease. 2014 Oct:6(Suppl 7):S712-9. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.03.15. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25383205]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCanning BJ, Chang AB, Bolser DC, Smith JA, Mazzone SB, McGarvey L, CHEST Expert Cough Panel. Anatomy and neurophysiology of cough: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel report. Chest. 2014 Dec:146(6):1633-1648. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1481. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25188530]

Fracchia MS, Diercks G, Cook A, Hersh C, Hardy S, Hartnick M, Hartnick C. The diagnostic role of triple endoscopy in pediatric patients with chronic cough. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2019 Jan:116():58-61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.10.017. Epub 2018 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 30554708]

Moore A, Harnden A, Grant CC, Patel S, Irwin RS, CHEST Expert Cough Panel. Clinically Diagnosing Pertussis-associated Cough in Adults and Children: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2019 Jan:155(1):147-154. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.09.027. Epub 2018 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 30321509]

Gibson PG, Vertigan AE. Management of chronic refractory cough. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2015 Dec 14:351():h5590. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5590. Epub 2015 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 26666537]

Bhalla K, Nehra D, Nanda S, Verma R, Gupta A, Mehra S. Prevalence of bronchial asthma and its associated risk factors in school-going adolescents in Tier-III North Indian City. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2018 Nov-Dec:7(6):1452-1457. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_117_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30613541]

. "ERS guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in adults and children." Alyn H. Morice, Eva Millqvist, Kristina Bieksiene, Surinder S. Birring, Peter Dicpinigaitis, Christian Domingo Ribas, Michele Hilton Boon, Ahmad Kantar, Kefang Lai, Lorcan McGarvey, David Rigau, Imran Satia, Jacky Smith, Woo-Jung Song, Thomy Tonia, Jan W.K. van den Berg, Mirjam J.G. van Manen and Angela Zacharasiewicz. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1901136. The European respiratory journal. 2020 Nov:56(5):. pii: 1951136. doi: 10.1183/13993003.51136-2019. Epub 2020 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 33214170]

Kastelik JA, Aziz I, Ojoo JC, Thompson RH, Redington AE, Morice AH. Investigation and management of chronic cough using a probability-based algorithm. The European respiratory journal. 2005 Feb:25(2):235-43 [PubMed PMID: 15684286]

Côté A, Russell RJ, Boulet LP, Gibson PG, Lai K, Irwin RS, Brightling CE, CHEST Expert Cough Panel. Managing Chronic Cough Due to Asthma and NAEB in Adults and Adolescents: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2020 Jul:158(1):68-96. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.12.021. Epub 2020 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 31972181]

Brightling CE, Ward R, Goh KL, Wardlaw AJ, Pavord ID. Eosinophilic bronchitis is an important cause of chronic cough. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1999 Aug:160(2):406-10 [PubMed PMID: 10430705]

Sadeghi MH, Wright CE, Hart S, Crooks M, Morice A. Phenotyping patients with chronic cough: Evaluating the ability to predict the response to anti-inflammatory therapy. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. 2018 Mar:120(3):285-291. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.12.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29508715]

Morice AH, Menon MS, Mulrennan SA, Everett CF, Wright C, Jackson J, Thompson R. Opiate therapy in chronic cough. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2007 Feb 15:175(4):312-5 [PubMed PMID: 17122382]

Ryan NM, Birring SS, Gibson PG. Gabapentin for refractory chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2012 Nov 3:380(9853):1583-9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60776-4. Epub 2012 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 22951084]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVertigan AE, Kapela SL, Ryan NM, Birring SS, McElduff P, Gibson PG. Pregabalin and Speech Pathology Combination Therapy for Refractory Chronic Cough: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Chest. 2016 Mar:149(3):639-48. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1271. Epub 2016 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 26447687]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKahrilas PJ, Howden CW, Hughes N, Molloy-Bland M. Response of chronic cough to acid-suppressive therapy in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Chest. 2013 Mar:143(3):605-612. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1788. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23117307]

Berkhof FF, Doornewaard-ten Hertog NE, Uil SM, Kerstjens HA, van den Berg JW. Azithromycin and cough-specific health status in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic cough: a randomised controlled trial. Respiratory research. 2013 Nov 14:14(1):125. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-125. Epub 2013 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 24229360]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePratter MR. Chronic upper airway cough syndrome secondary to rhinosinus diseases (previously referred to as postnasal drip syndrome): ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006 Jan:129(1 Suppl):63S-71S. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.63S. Epub [PubMed PMID: 16428694]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWakwaya Y, Ramdurai D, Swigris JJ. Managing Cough in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Chest. 2021 Nov:160(5):1774-1782. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.071. Epub 2021 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 34171385]

Brown KK. Chronic cough due to chronic interstitial pulmonary diseases: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006 Jan:129(1 Suppl):180S-185S. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.180S. Epub [PubMed PMID: 16428708]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGibson P, Wang G, McGarvey L, Vertigan AE, Altman KW, Birring SS, CHEST Expert Cough Panel. Treatment of Unexplained Chronic Cough: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2016 Jan:149(1):27-44. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1496. Epub 2016 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 26426314]

Vertigan AE, Theodoros DG, Gibson PG, Winkworth AL. Efficacy of speech pathology management for chronic cough: a randomised placebo controlled trial of treatment efficacy. Thorax. 2006 Dec:61(12):1065-9 [PubMed PMID: 16844725]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChamberlain S, Garrod R, Birring SS. Cough suppression therapy: does it work? Pulmonary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2013 Oct:26(5):524-7. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2013.03.012. Epub 2013 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 23524013]

Ryerson CJ, Abbritti M, Ley B, Elicker BM, Jones KD, Collard HR. Cough predicts prognosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology (Carlton, Vic.). 2011 Aug:16(6):969-75. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.01996.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21615619]

Koskela HO, Lätti AM, Purokivi MK. Long-term prognosis of chronic cough: a prospective, observational cohort study. BMC pulmonary medicine. 2017 Nov 21:17(1):146. doi: 10.1186/s12890-017-0496-1. Epub 2017 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 29162060]

Yousaf N, Montinero W, Birring SS, Pavord ID. The long term outcome of patients with unexplained chronic cough. Respiratory medicine. 2013 Mar:107(3):408-12. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.11.018. Epub 2012 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 23261310]

Birring SS, Murphy AC, Scullion JE, Brightling CE, Browning M, Pavord ID. Idiopathic chronic cough and organ-specific autoimmune diseases: a case-control study. Respiratory medicine. 2004 Mar:98(3):242-6 [PubMed PMID: 15002760]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWaring G, Kirk S, Fallon D. The impact of chronic non-specific cough on children and their families: A narrative literature review. Journal of child health care : for professionals working with children in the hospital and community. 2020 Mar:24(1):143-160. doi: 10.1177/1367493518814925. Epub 2019 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 30606033]

Mathur A, Liu-Shiu-Cheong PSK, Currie GP. The management of chronic cough. QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians. 2019 Sep 1:112(9):651-656. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcy259. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30380127]

Singh DP, Jamil RT, Mahajan K. Nocturnal Cough. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30335306]

Song DJ, Song WJ, Kwon JW, Kim GW, Kim MA, Kim MY, Kim MH, Kim SH, Kim SH, Kim SH, Kim ST, Kim SH, Kim JK, Kim JH, Kim HJ, Kim HB, Park KH, Yoon JK, Lee BJ, Lee SE, Lee YM, Lee YJ, Lim KH, Jeon YH, Jo EJ, Jee YK, Jin HJ, Choi SH, Hur GY, Cho SH, Kim SH, Lim DH. KAAACI Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines for Chronic Cough in Adults and Children in Korea. Allergy, asthma & immunology research. 2018 Nov:10(6):591-613. doi: 10.4168/aair.2018.10.6.591. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30306744]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence