Introduction

Low back pain is a ubiquitous symptom. It is the second most common complaint when visiting a provider in the United States.[1] It accounted for 4.4% of emergency department visits from 2000 to 2016.[2] The lifetime prevalence of back pain is approximately 70% to 85%.[3] The causes of low back pain range from muscle spasms and disc protrusions to more severe entities such as discitis, osteomyelitis, and malignancy. Imaging provides varied details based on modality. The most common modalities include radiographs, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Ultrasound (US) and nuclear medicine imaging are occasionally choices. The American College of Radiology enlists appropriateness criteria for evaluating back pain. Patients with uncomplicated back pain do not require imaging unless it persists for more than 6 weeks. However, patients with cauda equina syndrome, malignancy, suspected infection, or fracture require further imaging.[4]

Symptoms of cauda equina syndrome would include saddle anesthesia and bowel or bladder incontinence. Patients presenting with fever and low back pain or patients with a history of drug misuse or immunosuppression should lead to suspicion of an infection. While plain radiographs are usually the first imaging modality, depending on the acuity, medical condition, and general contraindications to imaging modalities, the appropriate modality merits consideration. As a broad rule, whenever there is a concern for infection, or there is a suspicion of malignancy, contrast-enhanced studies are the recommended approach. ACR appropriateness criteria help in choosing the right modality in a variety of circumstances. CT is the imaging modality of choice in patients with suspected fractures. MRI is the modality of choice for patients who are possible candidates for augmentation procedures. MRI is also highly sensitive for evaluating tumors and metastasis. It is also the modality of choice for assessing cord compression.

Anatomy

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy

The lumbar spine consists of 5 lumbar vertebral bodies. There are many anatomical variants; however, identifying a transitional vertebra at the lumbosacral junction as lumbarization of S1 or sacralization of L5 clinically helps during surgical management. The attachment of the iliolumbar ligament and the vertebral body's size helps identify the L5 vertebral body; the ligament extends from the L5 transverse process to the iliac crest. The spinal cord ends approximately at the level of L1-L2. The group of nerve roots caudal to this forms the cauda equina, which consists of free-floating nerve roots in the central canal as they exit at the corresponding levels in the lumbosacral spine.

The disc spaces are composed of the nucleus pulposus and annulus fibrosis. The standardized spine nomenclature is based on recommendations from the American Society for Spine Radiology, the American Society for Neuroradiology, and the North American Spine Society. In 2014, Lumbar Disc Nomenclature: version 2.0 was released, updating the original version from 2001.[5] The disc herniations are an extension of the disc material beyond the confines of the disc space. Posterior disc herniations contribute to nerve impingements. Disc herniations are classified based on the circumference of disc involvement; when less than 25% of the circumference of the disc is involved, it is termed a protrusion, and when it involves greater than 25% of the circumference, it is called a bulge. When protrusions have a length greater than the width, they are called extrusions (see Image. Lumbar Spine MRI, Disc Extrusion). When the extruded disc segment loses contact with the disc, it is called a sequestered disc. In the axial plane, disc protrusions are classified based on their location, which is central, paracentral, foraminal, and extraforaminal. Depending on the location of the disc protrusion, different nerve roots are involved. For example, a paracentral disc protrusion affects the traversing lower-level nerve root, whereas a foraminal disc protrusion affects the exiting nerve root at the same level.

Plain Films

Imaging Modalities

There is a wide array of imaging modalities for evaluating the lumbar spine. The type of test depends on the pathology, the amount of radiation involved, contraindications, and any allergy to contrast. The American College of Radiology considers these and has recommendations on the kind of test based on symptoms. ACR appropriateness criteria can help to select the right imaging modality based on suspected pathology for symptoms such as suspected spine trauma, low back pain, low back pain with fever, etc.[4][6]

Plain Radiograph

Radiographs are economical, portable, and readily available. They are the first-line modality for evaluating back pain. Radiographs can evaluate vertebral body height, displaced fractures, and dislocations. They help assess the stability of the spine with flexion and extension views. However, the evaluation of nondisplaced fractures, metastases, and soft-tissue abnormalities is subject to overlying hardware, positioning, and bowel gas limitations. The radiation dose from radiographs also limits their use in pregnant patients.

Computed Tomography

CT is a reliable method for evaluating the lumbar spine and provides great bony detail for assessing trauma, nondisplaced fractures, complex fractures, scoliosis, pre, and postoperative patients (see Image. Grade II Spondylolisthesis, CT). CT is beneficial following surgery in evaluating the surgical hardware and bone graft material, which are not well assessed on MRI. CT myelograms are useful in patients with various spinal equipment and in patients who have a contraindication for MRI. These take place after instilling a radiopaque dye into the subarachnoid space by lumbar puncture under fluoroscopy or CT guidance.[7] CT myelogram is also important for diagnosing occult sites of CSF leak following lumbar spine surgery or trauma.[8] Contraindications for CT myelogram include pregnancy and other general contraindications for a lumbar puncture, such as severe bleeding disorders and elevated intracranial pressure.

Magnetic Resonance

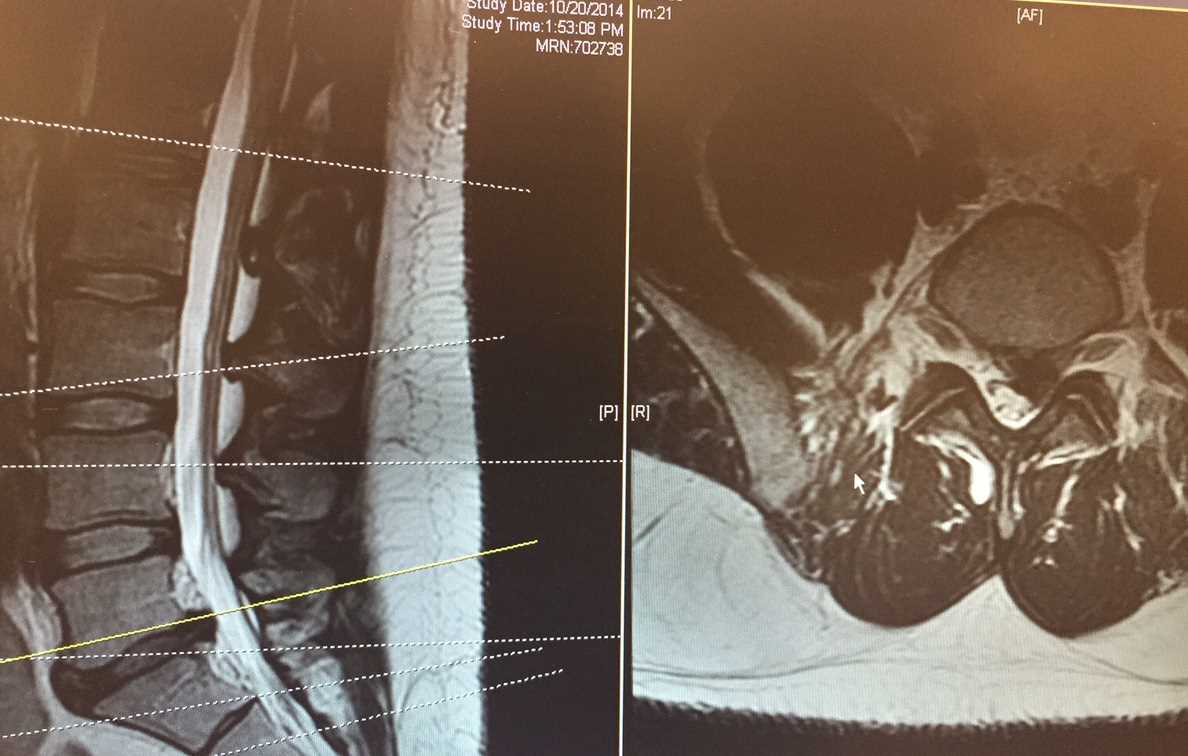

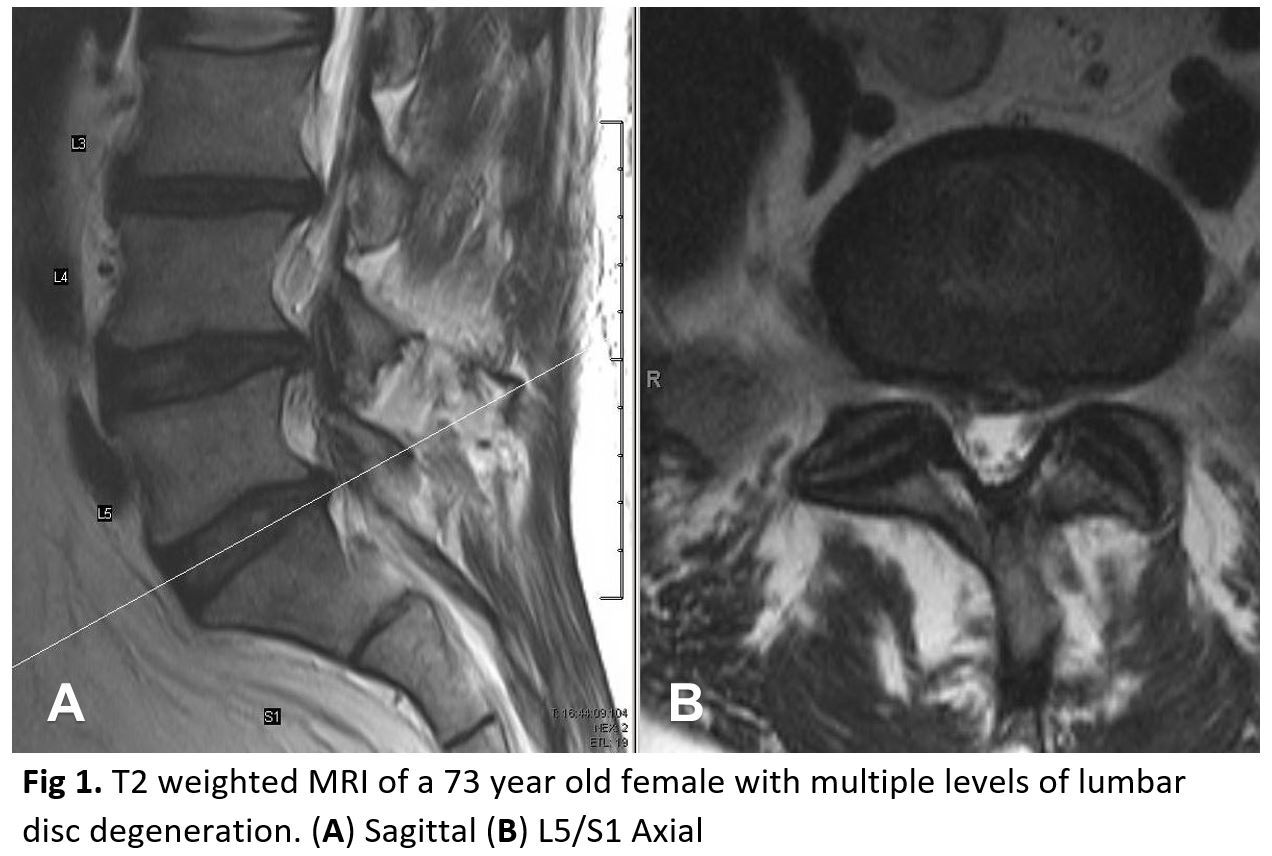

MRI is one of the most sensitive and specific modalities for evaluating the lumbar spine. Moreover, radiation has no side effects (see Image. Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Lumbar). It provides information about the vertebral bodies, disc spaces, and spinal canal, including the meninges, spinal cord, conus, cauda equina, and exiting nerve roots. Multiple sequences are obtained in different planes, each of which helps evaluate various pathologies (see Image. Lumbar Disc Degeneration, Multiple Levels). The most common sequences include sagittal and axial T1 and T2 and a sagittal STIR (short tau inversion recovery) (see Image. Sagittal MRI of Lumbar Spine With Spondylolisthesis, L3-4 and L4-5). Post-contrast T1 weighted sequence is useful for evaluating spinal infections, postoperative complications, vascular malformation, primary spinal tumors, and metastases. Prostate metastasis, frequently visible in the lumbar spine, can also be assessed on MRI. Complications associated with metastatic disease, such as cord compression, can also be diagnosed on MRI. STIR sequences are beneficial in assessing marrow edema, which produces an increased signal on these sequences.[9][10][11]

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography helps evaluate the lumbar spine in neonates. During a bedside evaluation, it can provide information on congenital abnormalities of the spinal cord and help assess CSF pulsations. In adults, it helps assess for superficial collections and plan percutaneous interventions.

Nuclear Medicine

Bone scans using radioactive tracer technetium 99m methylene diphosphonate help evaluate active bone formation in the body, like osteoblastic metastases from prostate cancer. However, fractures can also appear as false positives on bone scans performed for metastasis. F-18 FDG-PET/CT involves an injection of a radiopharmaceutical, 18F FDG, which is seen preferentially at sites of abnormal glucose metabolism. A fused image of a PET scan and a CT scan of the whole body helps to localize the metabolic abnormality accurately. FDG PET scans help evaluate bony metastases and spinal cord masses. However, they can also be positive in infections such as vertebral body osteomyelitis, as there is an altered glucose mechanism at the site of the infection.

18F NaF PET/CT is a more recent radiotracer imaging for evaluating osseous metastasis and is superior in imaging quality compared to a technetium 99 bone scan.[12]

Angiography

Angiography can help identify and treat vascular malformations in the lower spine, including arteriovenous malformations and dural fistulas. In patients with trauma, they can help identify and direct treatment for arterial pseudoaneurysms and blood leaks. Preoperative embolization can be performed for bone tumors in the spine to reduce blood loss during surgery.

Clinical Significance

The lumbar spine pathology is myriad but can be classified anatomically into bone, disc, meninges, spinal cord, or paraspinal regio lesions. Choosing an appropriate imaging modality provides sufficient information based on the etiology (trauma, congenital, degenerative, infective, vascular, and neoplasm). The more common conditions are discussed below.

Degenerative Disc Disease (DJD)

DJD is the most common etiology for back pain and increases with age. Mechanical stress and trauma are also significant contributors. A healthy disc is hyperintense on the T2 weighted sequence. Aging produces changes in the disc space signal. There are also associated changes in the endplates termed Modic changes.[13][14]

- Modic type I: Linear edema signal along the endplates, which is hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2 sequences

- Modic type II: Linear fat signal along the endplates, which is T1 and T2 hyperintense

- Modic type III: Linear sclerotic signal along the endplates, which T1 and T2 hypointense

Changes in the disc, along with facet arthropathy, lead to spinal stenosis. Disc herniations have been explained under the heading of anatomy. However, spinal stenosis can also occur from a variety of other etiologies, including congenital narrowing of the central canal from shortened pedicles, epidural masses, traumatic fractures, and fat deposition in the epidural space (epidural lipomatosis).

Discitis Osteomyelitis

It is an infection of the intervertebral disc and the adjacent vertebral bodies. Hematogenous spread is the most common etiology, followed by postoperative complications or following trauma. Clinically, patients can present with long-standing low back pain along with fever. MRI is the appropriate modality for evaluating spinal discitis or osteomyelitis. There is an abnormal signal within the involved dis,c, marrow edema, and endplate irregularity in the adjacent vertebral bodies. Post-contrast MRI will accurately delineate the extent of disc involvement and its extension into the adjacent vertebral bodies, paraspinal region, and spinal canal. It will also characterize the spinal canal extension into epidural, intradural, and leptomeningeal involvement. 3D reconstructions from CT may be useful for surgical hardware placement if required. The clinician can drain the paraspinal abscess with the help of CT or ultrasound. Occult spinal infections can be better evaluated with WBC-tagged nuclear medicine imaging.

Spinal Canal Masses

These are classified from the inside out as intramedullary, extramedullary-intradural, and extradural masses. MRI with contrast is the most appropriate imaging for spinal canal mass evaluation. The most common masses in each category are listed below.

The common intramedullary mass lesions are tumefactive demyelination, tumors, and vascular malformations. Most tumors will expand the spinal cord and have edema, hemorrhage, and an enhancing component. While tumefactive demyelination may happen in masses similarly tolikeitial imaging, it will improve after appropriate treatment. Serpegenous flow voids and sometimes subarachnoid hemorrhage may appear in the case of vascular malformations. MRA of the spine and 3D MR sequences will help localize and plan intervention and angiograms in vascular lesions. However, conventional angiography is the diagnostic imaging of choice for evaluating the origin of the arteriovenous malformation (AVM) and dural fistulas.

The extramedullary-intradural masses are usually comprised of meningiomas, schwannomas, intradural lipomas, epidermoids, arachnoid cysts, and metastases. These are seen external to the cord but within the dura. In axial images, there is a widening of the subarachnoid space with the displacement of the cord. Most of these lesions have typical imaging characteristics on MRI.

Extradural lesions include epidural abscess, epidural hematoma, tumors of the adjacent vertebral bodies, and epidural lipomatosis. The dura lifts off from the vertebral body or lamina attachments, and multiplanar images from MRI best characterize these lesions.

Trauma

Elaborate thoracolumbar spine injury classification systems exist that classify vertebral body fractures and dictate the treatment algorithm. Traditionally, vertebral body fractures are classified based on the number of columns involved. The 3 column model describes:

- The anterior column comprises the anterior longitudinal ligament and the anterior half of the body.

- The middle column consists of the posterior half and the posterior longitudinal ligament.

- The posterior column consists of the supra and interspinous ligaments, ligamentum flavum, and facet joints.

Fractures involving 2 or more columns are termed unstable. CT is the imaging modality of choice in acute trauma to delineate the bony abnormalities, and MRI to evaluate ligamentous injuries. Additionally, MRI in spinal trauma will provide information on epidural hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, cord compression, and cord transections. Any neurological deficits associated with spinal trauma should undergo an evaluation with an MRI. When lumbar spine fractures are detected, the clinician should also assess for visceral injury, including the peritoneum and retroperitoneum. Approximately 51% of patients with transverse fractures also have a concomitant abdominal visceral injury.[15]

Postoperative Lumbar Spine Imaging

With an increasing number of spine surgeries, imaging of postoperative complications has also become very common. Complications are classified as early and late complications. Early complications include hardware malpositioning, hematoma, infection, and CSF leakage. Late complications include recurrent disc herniation, failure of fusion, hardware failure, infection (discitis, osteomyelitis, prevertebral, paraspinal, and epidural abscess), epidural fibrosis, and arachnoiditis.[16] Recurrent disc herniation is distinguishable from granulation tissue that develops following surgery. On imaging, recurrent disc enhances less avidly than granulation tissue. Disc herniation can have a rim-enhancing pattern. While hardware failure and non-fusion can be evaluated on CT, MRI is necessary to diagnose most of the other postoperative complications like epidural fibrosis and arachnoiditis.

In conclusion, the lumbar spine is assessable using multiple modalities, and these modalities are complementary to each other. Choosing appropriate modalities wisely leads to better patient care, proper diagnosis, and improved healthcare costs.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Chou R, Deyo RA, Jarvik JG. Appropriate use of lumbar imaging for evaluation of low back pain. Radiologic clinics of North America. 2012 Jul:50(4):569-85. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2012.04.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22643385]

Edwards J, Hayden J, Asbridge M, Gregoire B, Magee K. Prevalence of low back pain in emergency settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2017 Apr 4:18(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1511-7. Epub 2017 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 28376873]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFarshad-Amacker NA, Farshad M, Winklehner A, Andreisek G. MR imaging of degenerative disc disease. European journal of radiology. 2015 Sep:84(9):1768-76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.04.002. Epub 2015 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 26094867]

Patel ND, Broderick DF, Burns J, Deshmukh TK, Fries IB, Harvey HB, Holly L, Hunt CH, Jagadeesan BD, Kennedy TA, O'Toole JE, Perlmutter JS, Policeni B, Rosenow JM, Schroeder JW, Whitehead MT, Cornelius RS, Corey AS. ACR Appropriateness Criteria Low Back Pain. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2016 Sep:13(9):1069-78. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.06.008. Epub 2016 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 27496288]

Fardon DF, Williams AL, Dohring EJ, Murtagh FR, Gabriel Rothman SL, Sze GK. Lumbar disc nomenclature: version 2.0: Recommendations of the combined task forces of the North American Spine Society, the American Society of Spine Radiology and the American Society of Neuroradiology. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2014 Nov 1:14(11):2525-45. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.04.022. Epub 2014 Apr 24 [PubMed PMID: 24768732]

Daffner RH, Hackney DB. ACR Appropriateness Criteria on suspected spine trauma. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2007 Nov:4(11):762-75 [PubMed PMID: 17964500]

Pomerantz SR. Myelography: modern technique and indications. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2016:135():193-208. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53485-9.00010-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27432666]

Malhotra A, Kalra VB, Wu X, Grant R, Bronen RA, Abbed KM. Imaging of lumbar spinal surgery complications. Insights into imaging. 2015 Dec:6(6):579-90. doi: 10.1007/s13244-015-0435-8. Epub 2015 Oct 2 [PubMed PMID: 26432098]

Pizones J, Izquierdo E, Alvarez P, Sánchez-Mariscal F, Zúñiga L, Chimeno P, Benza E, Castillo E. Impact of magnetic resonance imaging on decision making for thoracolumbar traumatic fracture diagnosis and treatment. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2011 Aug:20 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):390-6. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1913-4. Epub 2011 Jul 21 [PubMed PMID: 21779855]

Kumar Y, Hayashi D. Role of magnetic resonance imaging in acute spinal trauma: a pictorial review. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2016 Jul 22:17():310. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1169-6. Epub 2016 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 27448661]

Willson MC, Ross JS. Postoperative spine complications. Neuroimaging clinics of North America. 2014 May:24(2):305-26. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2014.01.002. Epub 2014 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 24792610]

Iagaru A, Young P, Mittra E, Dick DW, Herfkens R, Gambhir SS. Pilot prospective evaluation of 99mTc-MDP scintigraphy, 18F NaF PET/CT, 18F FDG PET/CT and whole-body MRI for detection of skeletal metastases. Clinical nuclear medicine. 2013 Jul:38(7):e290-6. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3182815f64. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23455520]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDudli S, Fields AJ, Samartzis D, Karppinen J, Lotz JC. Pathobiology of Modic changes. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2016 Nov:25(11):3723-3734 [PubMed PMID: 26914098]

Modic MT, Steinberg PM, Ross JS, Masaryk TJ, Carter JR. Degenerative disk disease: assessment of changes in vertebral body marrow with MR imaging. Radiology. 1988 Jan:166(1 Pt 1):193-9 [PubMed PMID: 3336678]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePatten RM, Gunberg SR, Brandenburger DK. Frequency and importance of transverse process fractures in the lumbar vertebrae at helical abdominal CT in patients with trauma. Radiology. 2000 Jun:215(3):831-4 [PubMed PMID: 10831706]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHerrera Herrera I, Moreno de la Presa R, González Gutiérrez R, Bárcena Ruiz E, García Benassi JM. Evaluation of the postoperative lumbar spine. Radiologia. 2013 Jan-Feb:55(1):12-23. doi: 10.1016/j.rx.2011.12.004. Epub 2012 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 22520556]