Introduction

One of the main challenges in surgery has long been to elaborate safe, effective, and technically feasible procedures for the best possible outcomes. Continuous progress in science and technology combined with cumulative experience in the field have refined indications for surgical treatment, prompted standardization of modern surgical techniques, and established comprehensive protocols in perioperative care. The most complex interventions can now be implemented with significantly reduced intraoperative trauma by using modern instruments and minimally invasive approaches. Surgical procedures became faster and safer, but complications are still prevalent, even in experienced hands.[1][2]

Surgeons are challenged by another conundrum: to accurately select the best candidates for surgical treatment. While technical aspects of surgery are still crucial, an accurate prediction of immediate and long-term outcomes becomes an important part of an elective procedure that guides preoperative testing.[3][4] Failure to identify patients at a high operative risk may be associated with inappropriate postoperative care and significantly increase in-hospital mortality.[5] Preoperative risk factors and surgical complexity are predictive of treatment costs.[6] Also, operative risk serves as a solid foundation for a future patient-surgeon relationship. Having the same understanding of the goals of surgical treatment and bearing the most realistic expectations about postoperative recovery and possible complications is important in a shared decision-making process.

The selection of patients for surgical treatment is still largely influenced by a surgeon’s personal experience and judgment. However, estimation of an individual risk/benefit ratio for a specific surgical procedure can help to more objectively adopt a nonoperative management strategy or select the best surgical procedure at the most appropriate point of time. This article aims to discuss the problem of operative risk, review common risk factors and available statistical models to predict adverse events after surgery, and speculate about some practical aspects of the operative risk assessment.

Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Function

It has been estimated that about 234 million major surgical procedures are performed every year worldwide.[7] Any surgical procedure can lead to complications. The average mortality associated with inpatient surgery fluctuates from 0.5% to 7%.[8][9][10][11][12] Approximately 2 to 3 out of 10 patients develop complications after an elective surgical procedure.[9][12] For the most common surgical procedures, some of the postoperative complications have been well recognized and accepted by the professional society as an unavoidable risk due to the nature of the disease and patient-related factors. For example, the long-term recurrence rate following inguinal hernia repair has been consistently reported as around 9% to 12%.[13] It seems impossible to reliably reduce this rate without comprehensive research projects and further development in the field. For some other surgeries, the risk of selected complications has been successfully reduced to minimal and currently reflects random and unpredictable events. A good example may be a common bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy with a stable incidence of 0.1%.[14][15] In many cases, postoperative complications are potentially preventable. It is a surgeon’s responsibility to evaluate the operative risk and provide patients with comprehensive counseling.

Operative risk, or surgical risk, can be defined as a cumulative risk of death, development of a new disease or medical condition, or deterioration of a previously existed medical condition that develops in the early or late postoperative period and can be directly associated with surgical treatment. The essence of the operative risk is usually attributed to a patient’s overall health and simplified to a total number of patient-related unfavorable factors. Patient-related risk factors may be classified as modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors. This classification is of the most clinical value since eliminating or modifying the risk factors can optimize the overall preoperative risk and improve outcomes. Some of the modifiable risk factors are smoking, alcohol intake, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, cerebrovascular disease, anemia, malnutrition, mental disorders, and medications. Non-modifiable risk factors are factors like age, gender, genetics, family history, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, history of stroke or myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or chronic kidney disease. It is important to realize that a universal list of surgical risk factors does not exist, and any patient’s characteristic may or may not be a risk factor, depending on a surgical procedure, type of anesthesia used, and particular complication implied. In addition, "operative risk" is a much more complex term that potentially encompasses all the variety of the disease-related, patient-related, surgery-related, or system-related factors:

- Disease-related factors (e.g., the nature and the severity of a surgical condition)

- Patient-related factors (e.g., anatomical features, past surgical history, comorbidities, functional reserve, social status, lifestyle)

- Surgery-related factors (e.g., surgeon’s knowledge, technical and decision making skills, experience, and operative activity; anesthesia; sterility; operative access and exposure; type of the procedure and its complexity; overall surgical trauma; the level of contamination and antimicrobial prophylaxis)

- System-related factors (e.g., quality of preoperative and postoperative care, follow-up, rehabilitation, lifestyle modification)

- Unpredictable and random factors

Issues of Concern

Popular Surgical Risk Prediction Models

Several surgical risk-predicting models have been used in routine clinical practice. The present review does not aim to perform an extensive comparative analysis between them but instead introduces those most commonly used. All available models were created and validated on a unique sample of patients, utilize different predictors, and intend to predict different outcomes, which complicates a direct comparison between them. It also should be remembered that the risk prediction system refers to populations rather than individuals, meaning that an “individual risk” is a large statistical assumption.

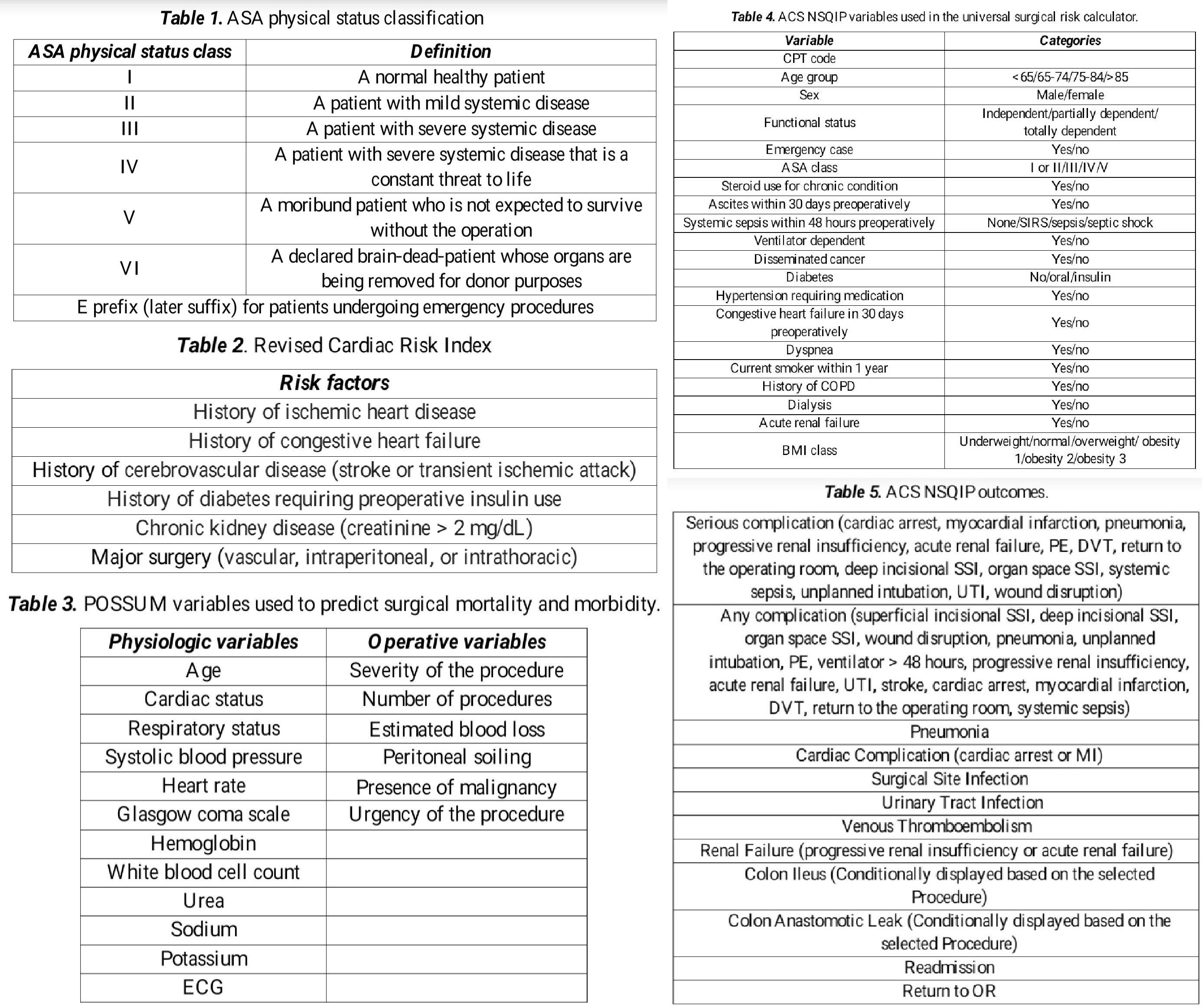

American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) Risk Assessment Model (Table 1)

In 1941, the American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) developed an elaborate classification of patients' physical status, which has undergone several revisions. The application of this classification (Table 1) has become standard practice worldwide before any surgical procedure that involves an anesthesiologist. ASA functional class is a valid and reliable tool to assess a patient’s preoperative general health[16] that has a moderate association with cardiac arrest[17] and in-hospital mortality.[16][18]

ASA functional class is commonly believed to be one way to estimate surgical risk since anesthesia is an integral part of a surgical procedure. However, the main purpose of the ASA score is not to predict the outcome since the score is semi-quantitative, quite subjective.[19] and does not consider many important surgical risk factors. It is rather a convenient tool to estimate the patient’s physiological reserve before surgical treatment. ASA class may guide additional preoperative testing.[4] Patients with ASA class 3 or 4 may need anesthesia to consult before surgery to plan for appropriate anesthesia ahead. Based on the ASA score and comorbidities, patients may also require evaluation by other specialists, such as internal medicine, cardiology, pulmonology, or infectious disease, to better assess operative risk and suggest preoperative evaluation and optimization.

All available operative risk prediction models can be separated into two groups:

- Scoring systems to predict cardiac risk

- Scoring systems to predict overall surgical risk

Revised Cardiac Risk Index Model (Table 2)

Major adverse cardiovascular events are important determinants of postoperative morbidity and mortality in stable patients undergoing non-cardiac surgical procedures.[20] The incidence of perioperative cardiovascular events after major noncardiac surgery in the United States has recently been reported as 3%.[21] A Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) has been suggested to estimate the perioperative risk of a major cardiac event: cardiac death, nonfatal cardiac arrest, or nonfatal myocardial infarction.[22] This tool was developed within a cohort study of 2,893 patients and subsequently validated on 1,422 patients older than 50 years undergoing major non-cardiac surgery.

The incidence of a major cardiac event correlates with the amount of predictors: 0 predictors = 0.4%, 1 predictor = 0.9%, 2 predictors = 6.6%, and 3 predictors = >11%. A systematic review demonstrated that the RCRI discriminates moderately well (AUC = 0.75) between patients at low versus high risk for cardiac events after mixed noncardiac surgery.[23] The predictive value of death and cardiac events after vascular surgery was lower.[23] The RCRI has been criticized for the relatively low study sample, inadequate categorization of surgical procedures, and only moderate predictive ability.[20]

American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) Based Model (Table 3)

Another cardiac risk prediction model has been developed based on the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) database, including 211,410 patients to predict myocardial infarction or cardiac arrest within 30 days after surgery.[20] A multivariate logistic regression analysis of the database demonstrated that age, ASA class, functional status, abnormal creatinine (> 1.5 mg/dL), and type of surgery were significantly associated with perioperative cardiac risk. This risk prediction model had a high discriminative ability (AUC = 0.88). An interactive risk calculator, commonly referred to as Myocardial Infarction and Cardiac Arrest (MICA) calculator, is available online. Some limitations of the model include, but are not limited to, a lack of data for some possible surgical risk factors such as coronary artery disease. However, it is worth mentioning that none of these cardiac risk prediction models have been externally validated within an appropriately sized cohort.

It is generally recommended to use one of the above-mentioned models to predict cardiac risk. For low-risk patients, no further preoperative testing is warranted. For patients at higher cardiac risk, a question should be raised whether further cardiovascular testing would change management. A stepwise approach to perioperative cardiac assessment has been elaborated and validated by the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology.[24] This system relies on prospectively collected data on more than 1 million surgical procedures performed in 252 hospitals in the United States. The system determines the risk of cardiac morbidity based on three major parameters: inherent cardiac risk of a surgical procedure, the presence of active cardiac conditions, and the patient’s functional capacity. Today, it is the most useful evidence-based algorithm to adjust cardiac risk before non-cardiac surgery.

Physiological and Operative Severity Score for Enumeration of Mortality and Morbidity (POSSUM) Model (Table 3)

POSSUM became one of the first models suggested to calculate the risk of operative mortality and morbidity in general surgery.[25] The system uses 12 physiological predictors and 6 procedure-related predictors to estimate the outcome.

There is evidence that the POSSUM score may overestimate current mortality and morbidity after surgery.[26][27][28] The Portsmouth POSSUM (P-Possum) score has been elaborated to overcome the problem of higher predicted mortality compared to observed mortality in low-risk patients, and an online calculator is available. P-POSSUM has proved to be a better risk prediction model by a large prospective study.[26] Another modification to the original POSSUM operative risk prediction system (Cr-POSSUM) has also been developed to better address some specific features of colorectal patients.[29]

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) Model

ACS NSQIP was created to collect high-quality standardized data on preoperative risk factors and postoperative complications from participating hospitals within the United States. Information from 393 hospitals and 1,414,006 patients was collected and successfully used to develop a universal surgical risk calculator to predict one of 9 adverse outcomes within 30 days after surgery based on 21 patient-related variables and the planned surgical procedure according to the Current Procedural Terminology code (CPT code).[30] A recently updated version of the calculator based on 3.8 million surgical procedures consists of 20 variables to predict 15 outcomes and is available online. This is the most accurate patient- and surgery-specific tool to estimate the operative risk and guide shared decision-making.[31] All patient-related risk factors and outcomes are listed in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. One of the unique features of the calculator is an option to adjust operative risk based on the surgeon's experience.

ACS NSQIP Variables Used in the Universal Surgical Risk Calculator (Table 4)

ACS NSQIP Outcomes (Table 5)

Clinical Significance

Calculation of an operative risk is not sufficient for shared decision making. Prediction of the potential benefit of an intervention is another important part of the risk/benefit ratio estimation. The risk of mortality of 10% is inappropriately high for any patient undergoing an elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy and does not favor surgical treatment. However, mortality as high as 70% may still be acceptable for a patient with multiple comorbidities and a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. The potential benefit from surgery is better estimated based on the published data on immediate and long-term results or surgery department audit and evaluation reports. The surgeon’s personal experience is also important to consider, but it is biased by definition unless the outcomes were verified within a formal research project. The art of medicine, however, will always play an important role in decision making, especially in complex cases. Despite being subjective, the physician’s feeling of a possible unfavorable outcome has a reasonable predictive value.[32]

Surgery is a highly dynamic field with continuously improving outcomes due to advances in technology and better intraoperative and postoperative care. Elaboration of high-volume centers contributes to better outcomes for some complex procedures. Progress in surgical education also aims to minimize the risks of surgery performed by an inexperienced physician-in-training. However, these processes may be at different stages of development, even within the same geographical region. Hence, there is always some discrepancy between predicted and observed mortality and morbidity. Every surgical department and surgeon must make an effort to log and track immediate and long-term outcomes to compare predicted and observed morbidity with the national average.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Preoperative modification of the risk factors is the most effective way to prevent postoperative morbidity and mortality. Appropriate postoperative care can also diminish operative risk if contemplated before surgical treatment. After surgery, admission to a critical care unit may prevent postoperative complications more effectively than escalating postoperative care once complications develop.[5] Of note, the operative risk is the risk of both immediate and long-term adverse events. For example, evidence-based prevention of venous thromboembolism after surgical treatment of cancer often implies chemoprophylaxis that extends beyond discharge from the hospital.[33]

An expert opinion is of the lowest value in evidence-based medicine. Hence, a surgeon’s experience and expertise cannot be used solely to guide risk management. Elaboration of the modern risk prediction models aims to establish a standardized and convenient tool for surgical risk calculation that may be used by any physician regardless of specialty and experience. Creating a comprehensive statistical model that would include all possible risk factors, quantitatively measure them, consider all possible interactions between them, and be suitable for any patient and the surgical condition seems to be a difficult task for future generations of physicians and scientists.

For all elective cases, it is important to get the patient assessed in a preoperative clinic, which is usually run by the anesthesiologists, nurses, and internists. All patients with risk factors should be thoroughly evaluated before being cleared for surgery. To minimize risk, an interprofessional team approach will result in the best outcomes. Initial screening is typically performed by the nurse providing initial management of the case. The nurse should access vitals, screen for food or fluid intake before the procedure, and identify co-morbidities that may place the patient at high risk. If potential drug-drug interactions are present, a pharmacist should be consulted to make recommendations on managing concerning medication issues. The nurse anesthetist usually performs a more detailed preoperative assessment. If any concerns develop, the preoperative team should involve an interprofessional decision involving nursing, anesthesia, and the surgeons to develop a safe plan to continue the operation or, if possible, delay the procedure until appropriate precautions are taken. Working together as a team, educating the patient and family, and minimizing risks will result in the best outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

References

Healey MA,Shackford SR,Osler TM,Rogers FB,Burns E, Complications in surgical patients. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2002 May [PubMed PMID: 11982478]

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. 2000:(): [PubMed PMID: 25077248]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceO'Neill F,Carter E,Pink N,Smith I, Routine preoperative tests for elective surgery: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2016 Jul 14 [PubMed PMID: 27418436]

Martin SK,Cifu AS, Routine Preoperative Laboratory Tests for Elective Surgery. JAMA. 2017 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 28787493]

Pearse RM,Harrison DA,James P,Watson D,Hinds C,Rhodes A,Grounds RM,Bennett ED, Identification and characterisation of the high-risk surgical population in the United Kingdom. Critical care (London, England). 2006 [PubMed PMID: 16749940]

Davenport DL,Henderson WG,Khuri SF,Mentzer RM Jr, Preoperative risk factors and surgical complexity are more predictive of costs than postoperative complications: a case study using the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database. Annals of surgery. 2005 Oct [PubMed PMID: 16192806]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWeiser TG,Regenbogen SE,Thompson KD,Haynes AB,Lipsitz SR,Berry WR,Gawande AA, An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modelling strategy based on available data. Lancet (London, England). 2008 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 18582931]

Khuri SF,Henderson WG,DePalma RG,Mosca C,Healey NA,Kumbhani DJ, Determinants of long-term survival after major surgery and the adverse effect of postoperative complications. Annals of surgery. 2005 Sep [PubMed PMID: 16135919]

Ghaferi AA,Birkmeyer JD,Dimick JB, Variation in hospital mortality associated with inpatient surgery. The New England journal of medicine. 2009 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 19797283]

Noordzij PG,Poldermans D,Schouten O,Bax JJ,Schreiner FA,Boersma E, Postoperative mortality in The Netherlands: a population-based analysis of surgery-specific risk in adults. Anesthesiology. 2010 May [PubMed PMID: 20418691]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePearse RM,Moreno RP,Bauer P,Pelosi P,Metnitz P,Spies C,Vallet B,Vincent JL,Hoeft A,Rhodes A, Mortality after surgery in Europe: a 7 day cohort study. Lancet (London, England). 2012 Sep 22 [PubMed PMID: 22998715]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGlobal patient outcomes after elective surgery: prospective cohort study in 27 low-, middle- and high-income countries. British journal of anaesthesia. 2016 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 27799174]

Murphy BL,Ubl DS,Zhang J,Habermann EB,Farley DR,Paley K, Trends of inguinal hernia repairs performed for recurrence in the United States. Surgery. 2018 Feb [PubMed PMID: 28923698]

Chuang KI,Corley D,Postlethwaite DA,Merchant M,Harris HW, Does increased experience with laparoscopic cholecystectomy yield more complex bile duct injuries? American journal of surgery. 2012 Apr [PubMed PMID: 22326050]

Halbert C,Pagkratis S,Yang J,Meng Z,Altieri MS,Parikh P,Pryor A,Talamini M,Telem DA, Beyond the learning curve: incidence of bile duct injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy normalize to open in the modern era. Surgical endoscopy. 2016 Jun [PubMed PMID: 26335071]

Sankar A,Johnson SR,Beattie WS,Tait G,Wijeysundera DN, Reliability of the American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status scale in clinical practice. British journal of anaesthesia. 2014 Sep [PubMed PMID: 24727705]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNunnally ME,O'Connor MF,Kordylewski H,Westlake B,Dutton RP, The incidence and risk factors for perioperative cardiac arrest observed in the national anesthesia clinical outcomes registry. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2015 Feb [PubMed PMID: 25390278]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHopkins TJ,Raghunathan K,Barbeito A,Cooter M,Stafford-Smith M,Schroeder R,Grichnik K,Gilbert R,Aronson S, Associations between ASA Physical Status and postoperative mortality at 48 h: a contemporary dataset analysis compared to a historical cohort. Perioperative medicine (London, England). 2016 [PubMed PMID: 27777754]

Owens WD,Felts JA,Spitznagel EL Jr, ASA physical status classifications: a study of consistency of ratings. Anesthesiology. 1978 Oct [PubMed PMID: 697077]

Gupta PK,Gupta H,Sundaram A,Kaushik M,Fang X,Miller WJ,Esterbrooks DJ,Hunter CB,Pipinos II,Johanning JM,Lynch TG,Forse RA,Mohiuddin SM,Mooss AN, Development and validation of a risk calculator for prediction of cardiac risk after surgery. Circulation. 2011 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 21730309]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSmilowitz NR,Gupta N,Ramakrishna H,Guo Y,Berger JS,Bangalore S, Perioperative Major Adverse Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Events Associated With Noncardiac Surgery. JAMA cardiology. 2017 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 28030663]

Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, Thomas EJ, Polanczyk CA, Cook EF, Sugarbaker DJ, Donaldson MC, Poss R, Ho KK, Ludwig LE, Pedan A, Goldman L. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 1999 Sep 7:100(10):1043-9 [PubMed PMID: 10477528]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFord MK, Beattie WS, Wijeysundera DN. Systematic review: prediction of perioperative cardiac complications and mortality by the revised cardiac risk index. Annals of internal medicine. 2010 Jan 5:152(1):26-35. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-1-201001050-00007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20048269]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFleisher LA,Fleischmann KE,Auerbach AD,Barnason SA,Beckman JA,Bozkurt B,Davila-Roman VG,Gerhard-Herman MD,Holly TA,Kane GC,Marine JE,Nelson MT,Spencer CC,Thompson A,Ting HH,Uretsky BF,Wijeysundera DN, 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 25085962]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCopeland GP,Jones D,Walters M, POSSUM: a scoring system for surgical audit. The British journal of surgery. 1991 Mar [PubMed PMID: 2021856]

Prytherch DR,Whiteley MS,Higgins B,Weaver PC,Prout WG,Powell SJ, POSSUM and Portsmouth POSSUM for predicting mortality. Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enUmeration of Mortality and morbidity. The British journal of surgery. 1998 Sep [PubMed PMID: 9752863]

Curran JE,Grounds RM, Ward versus intensive care management of high-risk surgical patients. The British journal of surgery. 1998 Jul [PubMed PMID: 9692572]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGonzález-Martínez S,Martín-Baranera M,Martí-Saurí I,Borrell-Grau N,Pueyo-Zurdo JM, Comparison of the risk prediction systems POSSUM and P-POSSUM with the Surgical Risk Scale: A prospective cohort study of 721 patients. International journal of surgery (London, England). 2016 May [PubMed PMID: 26970177]

Tekkis PP,Prytherch DR,Kocher HM,Senapati A,Poloniecki JD,Stamatakis JD,Windsor AC, Development of a dedicated risk-adjustment scoring system for colorectal surgery (colorectal POSSUM). The British journal of surgery. 2004 Sep [PubMed PMID: 15449270]

Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL, Zhou L, Kmiecik TE, Ko CY, Cohen ME. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: a decision aid and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2013 Nov:217(5):833-42.e1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.07.385. Epub 2013 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 24055383]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCohen ME,Liu Y,Ko CY,Hall BL, An Examination of American College of Surgeons NSQIP Surgical Risk Calculator Accuracy. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2017 May [PubMed PMID: 28389191]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHartley MN,Sagar PM, The surgeon's 'gut feeling' as a predictor of post-operative outcome. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 1994 Nov [PubMed PMID: 7598397]

Lyman GH,Khorana AA,Kuderer NM,Lee AY,Arcelus JI,Balaban EP,Clarke JM,Flowers CR,Francis CW,Gates LE,Kakkar AK,Key NS,Levine MN,Liebman HA,Tempero MA,Wong SL,Prestrud AA,Falanga A, Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 23669224]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence