Introduction

Pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) is a surgical technique originally introduced by Robert Machemer.[1] The pars plana approach to the vitreous cavity allows access to the posterior segment to treat many vitreoretinal diseases. This procedure requires a great deal of technical skill and knowledge to ensure good outcomes. A successful vitrectomy can restore vision and improve the quality of life in patients suffering from many vitreoretinal diseases. However, the procedure can also be associated with complications. Although the chances are low when performed correctly, these complications can cause severe patient morbidity and blindness. Therefore, it is essential that clinicians have thorough knowledge regarding the topic, understand the procedure, when to use it, how to perform it, and post-operative management.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

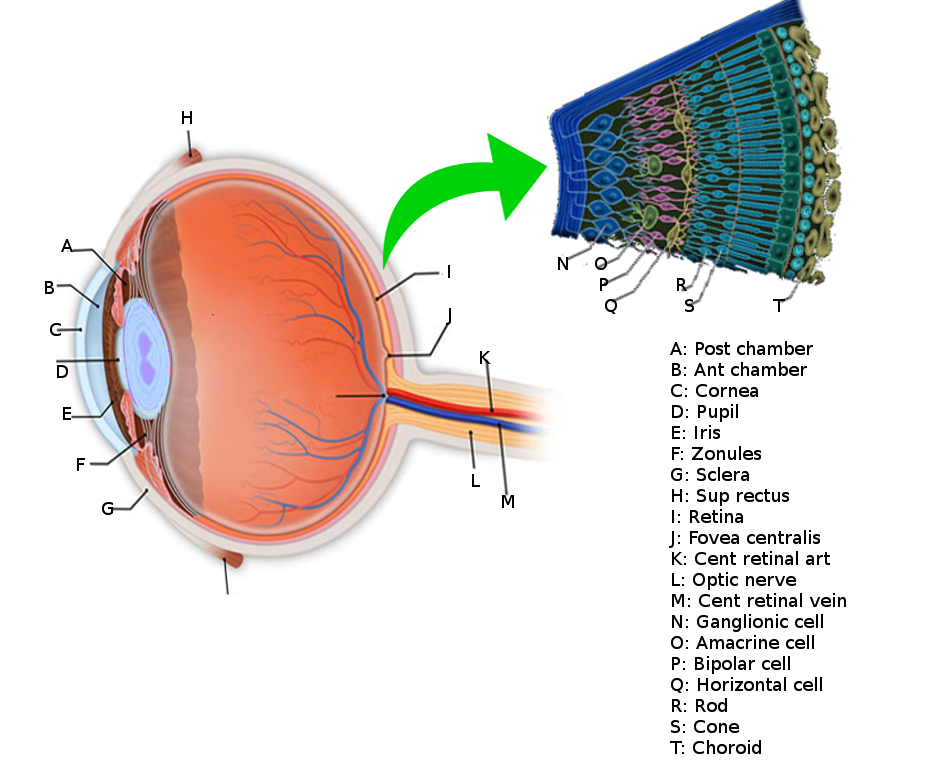

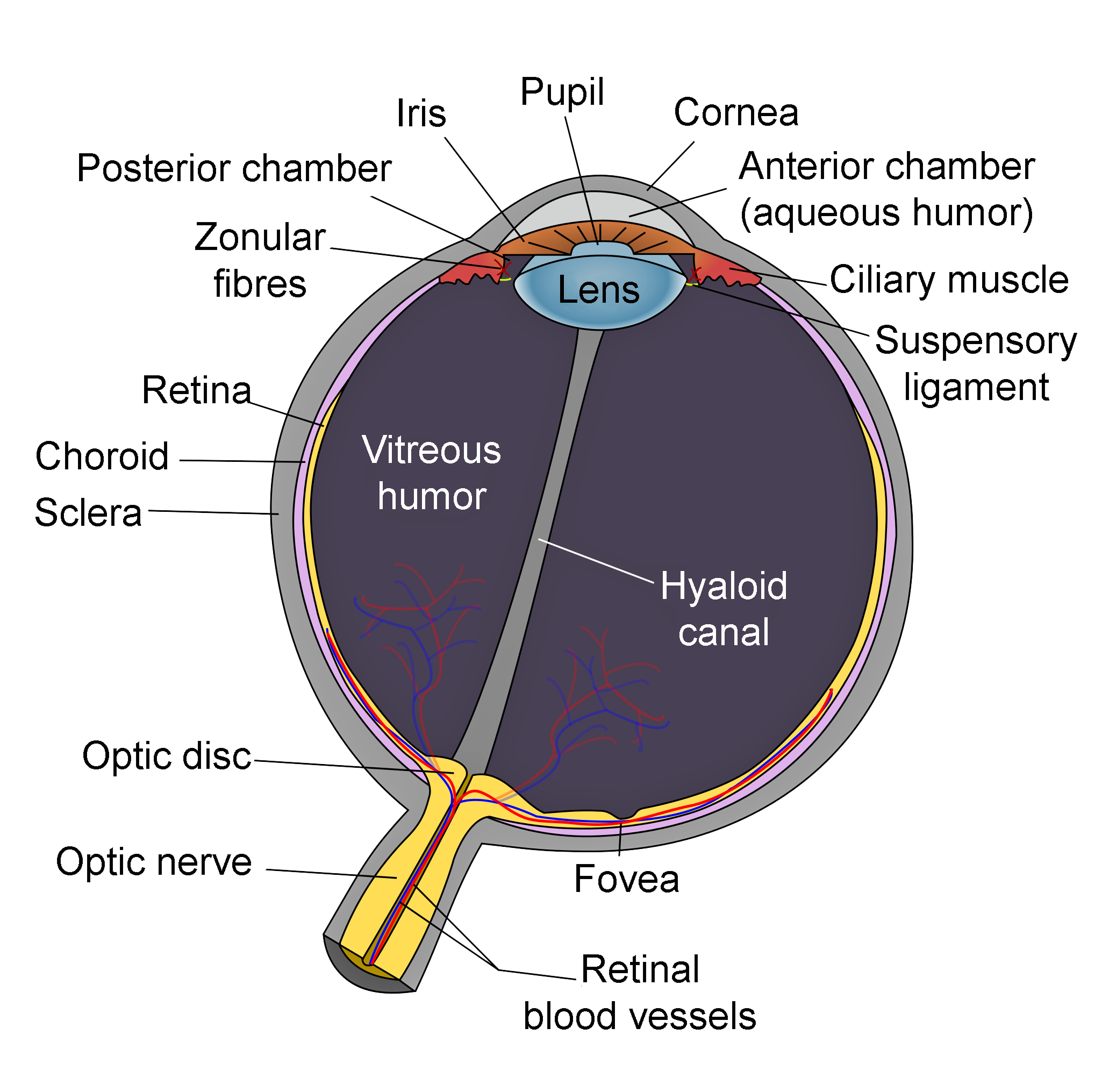

The retina is a neurosensory structure in the posterior segment of the eye that sends visual information to the optic nerve.[2] It contains neurons, glial cells, and blood vessels. Just like the CNS, all three of these structures play an essential role in the normal function of the retina and can be affected to varying degrees in retinal diseases. At a histological level, the retina consists of many layers. The inner limiting membrane separates the vitreous from the retina. Starting from inner to outer, the layers are the internal limiting membrane, nerve fiber layer, the ganglion cell layer, inner plexiform, inner nuclear, outer plexiform, outer nuclear, external limiting membrane, inner and outer segments of the photoreceptors, and the retinal pigment epithelial layer.[2] The external limiting membrane separates the cell bodies of the photoreceptors in the outer nuclear layer from the inner and outer segments of the photoreceptors. Knowledge about the retinal layers is important for PPV since the surgical technique can differ based on the pathology affecting the retinal layers.

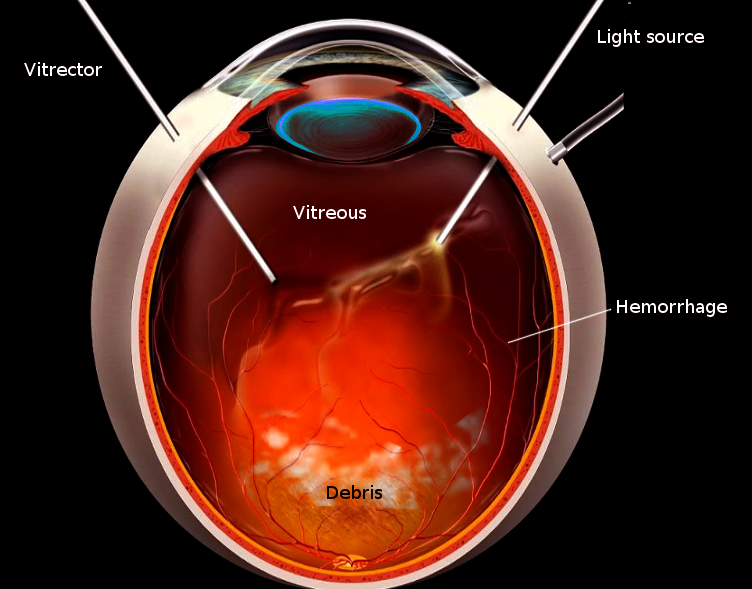

The vitreous is a gel filling the vitreous cavity and is adherent to the retina at focal points throughout the posterior cortical vitreous. Vitreous liquefaction occurs over time and can lead to vitreous detachment. A vitreous detachment from the retinal surface can lead to retinal tears and breaks, which can precede rhegmatogenous retinal detachments. This gel has to be removed during PPV so that any blood or products obstructing the visual axis can be cleared, and the retina can, therefore, be accessed. This cavity is replaced by normal saline infusion during the procedure. The choroid is a vascularized structure that provides structural support to the retina and blood supply to the outer retinal layers.

The vascular supply of the retina is vital to know for PPV. This knowledge can help prevent iatrogenic complications such as ischemia or hemorrhage during the procedure. Most of the blood supply to the inner retina comes from the central retinal artery, which branches off the ophthalmic artery that, in turn, comes from the internal carotid artery. The central retinal artery gives rise to the superior and inferior vascular arcades. Through the temporal and nasal branches, these four arteries provide the major blood supply to the inner retinal layers. The ophthalmic artery also gives rise to the long and short posterior ciliary arteries. The long ciliary arteries supply medial and lateral horizontal parts of the choroid. The short ciliary arteries supply the posterior part of the optic disc at the level of the choroid. Terminal branches of the short ciliary arteries provide additional blood supply to Bruch’s membrane and outer retina. As stated before, most of the blood supply to the outer retinal layers comes from the choroid. The veins of the retina follow the blood supply and drain into the central retinal vein. The retina does not contain lymphatic vessels.

In PPV, vitreous cavity access is through the pars plana; this represents the flat part of the ciliary body and is between the ora serrata and pars plicata. The ora serrata is a junction between the ciliary body and the retina. The pars plicata is the most anterior portion of the ciliary body and produces aqueous humor. The pars plicata is at the base of the iris. The pars plana is a structure that is around 4 mm long and starts further away from the corneal limbus. This landmark is chosen for PPV due to the convenient access to the vitreous while causing minimal ocular trauma. Furthermore, the pars plana does not serve a sensory function and has no involvement in producing aqueous or vitreous humor, which is important since the eye needs to endogenously replace the vitreous humor removed during PPV.

Indications

A vitrectomy can be considered for a variety of clinical scenarios since it enables the operating surgeon to access both the vitreous and retina. Below we list when PPV is indicated based on the type of pathology affecting the vitreous and/or the retina.

One of the most common indications for a PPV is when there is pathology that opacifies the vitreous and thus reduces vision. One example is a non-clearing vitreous hemorrhage. Many diseases can cause vitreous hemorrhage, such as proliferative diabetic retinopathy, trauma, posterior vitreous detachment, retinal detachment (RD), intraocular tumors, and retinal vascular diseases. Vitreous hemorrhage due to diabetic retinopathy can be treated with intravitreal anti-VEGF injections in some circumstances, and only in the absence of traction as well. In many cases, vitreoretinal surgeons will proceed with PPV without an injection if it is dense and unlikely to resolve with conservative therapy. If the vitreous hemorrhage does not clear despite conservative measures, then a vitrectomy is needed.

Vitrectomy is also performed for rhegmatogenous RD, which occurs when a prior retinal break or tear allows vitreous fluid to access the subretinal space. The fluid causes a separation of the layers of the neurosensory retina, which is how an RD is defined. The fluid can then propagate to involve the macula and cause sudden central vision loss. Patients who develop this pathology typically report a curtain coming down from their vision and can have visual field loss on an exam. If present for long enough to involve the macula, visual acuity will be compromised. If the macula is still attached, known as ‘mac-on,’ the surgery is more emergent to restore good visual acuity. If the detachment also involves the macula, it is known as a ‘mac-off’ RD. The surgery will be less emergent, and the visual prognosis is worse. When performing PPV for rhegmatogenous RDs, the subretinal fluid can be drained. A crucial part of the PPV is to remove any traction on the retinal breaks, which occurs through cryotherapy or laser to create a chorioretinal adhesion. This approach leads to a scar that prevents future access of intraocular fluid to the subretinal space. Intraocular tamponade can be achieved with air, gas, or silicone oil to prevent re-detachment until the chorioretinal adhesion becomes established around the breaks.[3]

PPV can also help relieve tractional forces on the retina that distort vision. A variety of pathologies can cause this, with the main principle being that PPV will relieve the mechanical traction that causes dysfunction of the neurosensory retina and thus vision impairment. Epiretinal membranes can be idiopathic in origin or occur secondarily to a variety of conditions such as retinal vascular disease, uveitis, laser therapy, or retinal breaks.[4] They can cause significant traction on the retina and impair central vision with metamorphopsia due to the forces on the neurosensory macula. PPV is indicated when an ERM affects vision. Macular holes occur when there is a tear or break in the macula. Patients with this pathology typically report wavy or blurry central vision that may even include a blind spot in the central vision. Peripheral vision is not affected unless there is comorbid pathology. Macular holes can occur due to a variety of diseases, including diabetic retinopathy and trauma, but most commonly occur due to aging when the vitreous tugs on the retina and mechanically causes a break or opening in the macula. PPV with a peel of the internal limiting membrane is appropriate for most macular holes. Some refractory or unusual macular holes can benefit from alternative approaches that are possible through PPV, such as inverted ILM flaps, the retracting door flap, or an autologous retinal transplant.[5][6][7][8] Vitreomacular traction can also occur spontaneously or in fibrovascular diseases that cause retinal scarring. Two common examples are sickle cell and diabetic retinopathy. These are acquired retinal diseases that can cause significant retinal non-perfusion. As both of these diseases progress, the ischemic retina causes angiogenesis and fibrovascular proliferation. Although the scar tissue typically forms away from the macula, the tangential traction on the macula and other regions of the neurosensory retina can distort vision. In these cases, PPV with the removal of the scar tissue causing traction is necessary.

If the traction from diseases like sickle cell or diabetic retinopathy progresses, patients can develop tractional RDs. In this case, the severe traction causes a separation of the neurosensory retina. The signs and symptoms of a tractional RD can be somewhat similar to a rhegmatogenous RD. PPV is done to relieve the traction, causing the detachment, which will also prevent the recurrence of tractional RD. If the traction causes a retinal break or tear, a tractional RD may be associated with a rhegmatogenous RD, as well. In these cases, PPV is even more critical and more urgent to prevent permanent vision loss. The retinal break or hole that formed secondary to traction must also be sealed to avoid recurrent rhegmatogenous RDs.

PPV can also be done to remove a submacular hemorrhage that affects vision. Submacular hemorrhages can occur due to choroidal neovascularization secondary to diseases that affect the outer retinal layers and the RPE, such as age-related macular degeneration. Surgical intervention is appropriate for a thick submacular hemorrhage. The hemorrhage itself can cause photoreceptor dysfunction through chemicals in the blood and/or mechanical forces on the photoreceptors that can even disrupt connections between them. If left untreated, retinal scarring with irreversible vision loss can occur. Initial surgical approaches included removal of subretinal hemorrhages, but this was associated with significant complications. Since then, approaches have focused on displacement rather than removal, which is achievable through an outpatient procedure without PPV.[9] However, this procedure achieves limited displacement. It can be a consideration for patients with high-risk systemic disease that would be poor surgical candidates. Better displacement further away from the fovea is achievable with subretinal approaches through PPV. These include subretinal injection of air, tissue plasminogen activator, and possibly anti-VEGF injections.[10][11]

PPV is needed when there is significant ocular trauma affecting the vitreous or retina. As stated before, PPV will be needed if trauma causes vitreous hemorrhage. PPV is most certainly necessary when there is an intraocular foreign body. Other traumatic pathology repaired by PPV includes retinal detachments, retinal breaks or tears, and even later post-traumatic endophthalmitis. Ocular trauma requires a thorough evaluation of other injuries since many of them constitute ophthalmic emergencies. These can include but aren’t limited to lid lacerations, corneal perforation, spikes in intraocular pressure that can cause irreversible optic neuropathy, lens or iris dislocation or subluxation, perforated globe, or a large retroorbital hemorrhage. These complications are even more likely when there is penetrating trauma. These emergencies may require additional surgical intervention from ophthalmic specialists. Therefore, the authors highly recommend an interprofessional approach to ocular trauma associated with multiple ocular injuries.

PPV is an option for diseases that cause intraocular inflammation. The most common type of pathology is endophthalmitis, a serious intraocular infection that can rapidly progress to blindness. Typically, systemic and intravitreal antibiotics are the treatment for bacterial endophthalmitis. A similar approach with antifungal therapy is the initial therapy for fungal endophthalmitis. However, if these measures fail or patients present with poor visual acuity at baseline, then PPV must be done for source control of the infection. PPV can also serve as a diagnostic procedure, such as in cases of unknown or persistent intraocular inflammation after appropriate laboratory testing. The surgery can sometimes be useful for implantation of intraocular agents such as ganciclovir or fluocinolone implants. Ganciclovir implants have been used in cases of cytomegalovirus infection in HIV patients. Fluocinolone implants are used for idiopathic posterior uveitis or some refractory uveitis following the exclusion of infections.

Other less common but possible indications of PPV include the retrieval of retained lens fragments after phacoemulsification, endoresection of intraocular tumors, and tumor biopsies. Although gene therapy is currently a newer indication for PPV, the pars plana direct subretinal approach without vitrectomy has been recently developed. This technique has also gained popularity for stem cell injections, displacement of submacular hemorrhages, biopsies, and many other indications that require access to the subretinal space. This approach allows surgeons to avoid the severe complications associated with pars plana vitrectomy.[12]

Contraindications

There are no true contraindications to PPV. Like most intraocular surgical procedures, the risk to patients with significant systemic co-morbidities may be the only contraindication to some elective procedures. However, for urgent indications of PPV to prevent permanent visual loss, a thorough evaluation by the anesthesiologist with appropriate preoperative clearance by specialty is indicated. The only published relative contraindication to PPV appears to be related to the diagnostic intervention for intraocular tumors. If sampling a poorly adhesive tumor during the PPV such as retinoblastoma, there is a good chance of dissemination.[13] The fear of spreading a poorly adhesive tumor during PPV is considered a convincing contraindication.[13] The spread of aggressive tumors can cause severe patient morbidity, which can even be fatal if the tumor metastasizes to an extraocular site.[14] However, this concept does not apply to all intraocular tumors. Furthermore, there are many times where PPV is necessary during the management of these aggressive intraocular tumors. Therefore, some clinicians suggest managing the tumors on a case by case basis; this may need an interprofessional approach with an ocular oncologist.

Equipment

Since PPV is always carried out in the operating room, standard operative equipment is required. However, since the surgery is very specialized, there is additional equipment needed. The following is a list of the standard equipment for PPV from the American Academy of Ophthalmology, along with some additional updated modifications.[15][16]

- Eyelid speculum

- Fine toothed forceps

- Wescott scissors

- Toothed forceps

- 20-gauge micro-vitreoretinal blade: this is rarely needed nowadays and mainly used to make larger sclerotomies. This blade may be needed for fragmatome lifting when removing intraocular foreign bodies.

- Infusion cannula with an inserter-cannula system

- Vitrectomy suction/cutting system

- Corneal lens ring

- Contact lenses focal or wide angles

- Trocar and cannulas. Gauges include 23, 25, and 27g.

- Indirect ophthalmoscope lenses with 20 and 30 diopter lenses

- Intraocular instrumentation for forceps, scissors, and pick

- Endolasers or indirect lasers

- Cryotherapy probes if required

- Perfluorocarbon liquid, gases, or silicone oil if necessary

- Inverting system for wide-angle vitrectomy lenses

- Visualization through microscopes. More recently, a heads-up display with 3 dimensional systems has gained popularity. Those provide advantages such as better ergonomics for surgeons and less light needed for visualization. It also improves teaching for students, residents, and fellows since everyone can see the 3-dimensional details of the procedure. It may even confer specific benefits for selected cases.

- Intraocular light pipes

Other specialized equipment may also be necessary in combined cases. Examples include PPV with anterior segment surgery or combined with oculoplastic surgery for lid and orbital cases.

Personnel

The surgery and post-op follow up are performed by a vitreoretinal surgeon. A resident or fellow under supervision by an attending can perform the surgery. If the surgery took place secondary to trauma, then additional ophthalmic surgeons may be needed depending on the repair. Furthermore, if there are complications such as raised intraocular pressure, then a glaucoma specialist may be required. In the case of intraocular tumors with orbital or systemic spread, an oculoplastic surgeon or other oncologic specialists may be necessary.

Preparation

Based on the acuity of the clinical condition, the PPV may be emergent with less time for preparation. The most important part of the preparation is determining what the indication is for the PPV. Therefore, a thorough ophthalmic exam with indirect ophthalmoscopy is needed to determine the structures involved. An ultrasound exam of the vitreous and retina may be necessary if vitreal opacities exclude a clear view of the retina. The ultrasound can pick up vitreal and/or retinal detachments in these circumstances. These measures not only determine the urgency of the procedure but also determine the type of procedure as well. Once the type of procedure has been scheduled, standard pre-operative measures ensue. The eye requires dilation before surgery.

Technique or Treatment

The procedure is performable under general anesthesia. Anesthesia is also possible via a peri or retrobulbar block. If needed, an eyelid block can be an option, as well. The patient should be draped in a sterile manner, just as with any surgical procedure. An eyelid speculum should be placed to keep the eye open. This process allows the surgeon to visualize the intraocular instrumentation and use lenses to see the fundus with indirect ophthalmoscopy or through the microscope. Trocar and cannulas are introduced through conjunctiva and sclera at the 2 o’clock, 10 o’clock, and inferotemporal regions, around 3-4 mm from the corneal limbus.

The infusion cannula gets inserted in the cannula inferotemporally. Visualization is most commonly through a non-contact wide-field system. However, in some macular pathology, a contact lens is placed on the cornea to visualize the fundus. The surgeon can now proceed to the vitrectomy.

The parameters should be set on the vitrectomy machine based on the instruments used and the surgeon’s preference. The core vitreous is removed. When removing vitreous near the posterior pole, a posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) may need to be induced if the posterior hyaloid is still attached to the macula and optic nerve. This process is possible by using high suction with the vitrector over the optic nerve. Steroids can help with visualization if this is difficult. If these fail, then the PVD is made using the bimanual techniques with the vitrectomy and a lighted pick. The peripheral vitreous is removable, but care must be made to avoid damage to the posterior lens in phakic patients. Scleral indentation is a technique used to help with visualization of the peripheral retina. The entire retina should be visualized to find any breaks, holes, tears, or detachments. This scrutiny includes the sclerotomy sites, which is very important to avoid iatrogenic breaks that may lead to later retinal detachment. Now that the vitrectomy is complete, the retina is accessible for additional interventions according to the pathology.

PPV is a common choice for a non-clearing vitreous hemorrhage. In this case, the vitrectomy removes the blood that is obstructing the visual axis. After clearing the retina for any other pathology like detachments, breaks, tears, or holes, the PPV is essentially over. In the case of retinal vascular diseases causing neovascularization, additional interventions like pan-retinal photocoagulation or intravitreal anti-VEGF injections will be necessary. If due to systemic disease like diabetes mellitus, then better glycemic control is needed.

PPV is also an option for retinal detachments. The ensuing steps differ based on the type of detachment. For rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, subretinal fluid is removed to flatten the retina. Any retinal breaks or tears that caused the detachment must be sealed with laser, cryotherapy, and gas or silicone added for tamponade to keep the retina attached until chorioretinal adhesion takes place.[17] In the case of tractional retinal detachments, fibrovascular membranes causing traction require removal. Traction can result from epiretinal membranes or fibrovascular proliferation in disease states like diabetic retinopathy. The tissue causing traction can have treatment with delamination or segmentation.

In the case of PPV performed for endophthalmitis, the vitrectomy helps with source control in aggressive infections where antibiotic penetrance alone is insufficient. A vitreous biopsy is also needed to culture the infectious agent and determine sensitivities to antibiotics or anti-fungal medications. After PPV, intravitreal injections of antibiotics or antifungals follow. For bacterial endophthalmitis, it is recommended to use vancomycin and ceftazidime for broad-spectrum coverage until culture data has returned.[18] If the patient has a severe penicillin or cephalosporin allergy, then consider tobramycin instead of ceftazidime. For fungal endophthalmitis, consider amphotericin B or an azole.[18]

When performed for penetrating ocular trauma, an interprofessional approach is required to treat additional defects such as corneal perforations, lens dislocations, or raised intraocular pressures. Blunt trauma may also be associated with additional defects that need repair. The vitreoretinal surgeon must remove any intraocular foreign body. Those that may cause further chemical or electric burns require removal emergently. Any retinal trauma such as breaks, tears, or holes should be treated to prevent future retinal detachments. Any retinal detachment should have prompt repair.

When performed for a dropped lens during cataract surgery, the crystalline lens carefully gets removed. A new lens is placed, if possible, according to the remaining capsular support. If not, intraocular lenses can be sclerally fixated, or an anterior chamber lens can get implanted. In the case of subluxation or dislocation of an intraocular lens, the process is a little bit more complicated. Any vitreous that is adherent to the lens requires removal first. A decision is necessary about how to ensure the lens now stays in place. Either that same lens gets used, or it is removed and replaced by a new lens as above.

If performing PPV for a diagnostic sampling of an ocular tumor, then the tumor can be sampled following removal of the vitreous. As stated before, care must be taken not to cause the spread of the tumor. This process typically occurs by fine-needle aspiration. Non-adhering tumors such as retinoblastoma usually aren’t biopsied due to the fear of this severe complication. The rest of the retina can be examined to see any insults that need repair.

Finally, once all of the therapeutic interventions of the vitrectomy have taken place, the operating surgeon can remove the cannulas. The instruments should be removed from inside the eye. Any vitreous that prolapses outside the sclerotomy sites can be cut with the vitrectomy probe or Westcott scissors. The incisions are most commonly closed with polyglactin sutures if needed, but plain gut sutures are also an option.[19]

Complications

There are many complications of PPV. Some of these can cause serious morbidity to the patient, including blindness. Just as with any surgical procedure, infection or hemorrhage can occur anywhere. There can also be technical difficulties that need a re-operation. However, it is important to review the specific subsets of these complications and how they can affect outcomes. Due to these reasons, careful post-op monitoring is necessary. Standard timeframes are at one day, one week, four weeks, and three months after the operation. Patients may need additional follow up if some of the following complications occur.

In the early post-op period, there can be a sudden rise in intraocular pressure. The increase in intraocular pressure can cause irreversible damage to the optic nerve and thus cause blindness. This complication typically receives treatment with pressure-lowering drops and/or anterior chamber or vitreous tap in certain circumstances. PPV can also cause corneal epithelial defects in the early post-op period, which can result in tearing, blurry vision, and photophobia. Sometimes they are planned when the cornea is scraped intraoperatively to visualize the fundus better. They are more likely to be persistent in patients with diabetes mellitus. Depending on the extent of the epithelial defects, conservative and operative interventions are available. A vitreous or choroidal hemorrhage may occur that needs further operative intervention. Additional early vascular complications include central retinal artery occlusion or cystoid macular edema. Care is necessary to avoid iatrogenic injury to blood vessels during the surgery. During surgery, iatrogenic retinal breaks or tears can occur that predispose to retinal detachment. Any retinal detachment will need a repeat PPV. Any retinal breaks or tears may need laser therapy and/or repeat PPV.

Patients can develop endophthalmitis on the scale of days to weeks after PPV. Patients can develop ocular pain, reduced vision, red-eye, and hypopyon. This condition is considered an ophthalmic emergency and needs urgent intervention to prevent permanent blindness. Options include intravitreal antibiotics, intravenous antibiotics, and repeat PPV. A repeat PPV is very likely in these circumstances. Patients can also develop iris neovascularization and neovascular glaucoma, which is more likely in disease states like diabetic retinopathy, which is believed to occur through the spread of angiogenic agents to the anterior chamber. The rise in intraocular pressure from this disease state can cause irreversible vision loss and is treated fairly similarly to early post-op rises in IOP. The only additional interventions focus on control of diabetes and diabetic retinopathy.

In the late post-op period, patients can develop cataracts. Cataracts can affect vision and may need operative intervention. PPV is associated with narrowing of the anterior chamber and secondary glaucoma if gas and silicone oil are used without appropriate positioning or in the absence of a peripheral iridectomy. A peripheral iridectomy is needed in some instances to prevent pupillary block but can also be used prophylactically for secondary glaucoma. This disease can be managed with intraocular lowering drops and/or surgical interventions.

Clinical Significance

PPV is a highly technical procedure that can save vision in many patients with acute or chronic vitreoretinal pathology. A good outcome can have a significant impact on the patient’s quality of life. Although the procedure carries a low overall risk, there is still a risk of severe complications. These can compromise vision or even cause blindness. However, expectant post-op surveillance and management can alleviate the burden of these complications. Overall, vitrectomies can serve a crucial role in preventing or even reversing vision loss.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients who develop blunt or penetrating trauma to the eye commonly have multiple ocular injuries. Most of these complications are under the management by additional ophthalmic specialists and are likely to be of sufficient severity to require operative intervention. Therefore vitrectomy may have to be delayed or expedited depending on the extent of the other ocular injuries. In this setting, it is essential to have a collaborative approach and effective communication between the ophthalmic surgeons and ophthalmology nursing staff. There is level three evidence for this approach to PPV if needed in the setting of multiple traumatic ocular injuries.[20] Examples include eyelid lacerations or defects, perforated globe, traumatic cataract, lens dislocation, spikes in intraocular pressure, or intraocular foreign bodies. Complications may also extend into the face, the orbit, or the central nervous system. Trauma involving these locations may require specialists from other disciplines as well. The ophthalmology specialty nurses are an integral part of the collaborative interprofessional team, as they can prepare the patient re-operatively, assist during PPV, and provide post-operative care and monitoring, reporting any concerns to the clinician staff. These interprofessional team efforts will guide outcomes to an optimal resolution in PPV procedures and aftercare. [Level 5]

Clinicians learn PPV during ophthalmology residency and vitreoretinal surgical fellowship. Studies have shown that ophthalmology residents perform a limited number of PPVs during their residency and are probably not competent at performing it by the end of their residency.[21] Only those who go into fellowship eventually become proficient at performing the surgery. Recently, there have been efforts to provide a standardized rubric to assess resident skill at performing PPV and provide prompt feedback.[21] Similar collaborative efforts like these are needed to improve resident education and proficiency at performing PPV. This paradigm would enable them to be an integral part of the team caring for those patients. Furthermore, it would provide them with tools to identify indications and complications associated with the procedure, thus allowing them to provide safer care when they become practicing physicians.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Schematic of Eye Anatomy. This image illustrates the anatomic relationships between the optic disc, optic nerve, fovea, sclera, choroid, vitreous humor, hyaloid canal, retina, retinal blood vessels, zonular fibers, iris, pupil, cornea, anterior chamber (aqueous humor), lens, posterior chamber, ciliary muscle, and suspensory ligament.

Contributed by R.H. Castilhos and Jordi March i Nogué (CC by SA-3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en)

References

Scott MN, Weng CY. The Evolution of Pars Plana Vitrectomy to 27-G Microincision Vitrectomy Surgery. International ophthalmology clinics. 2016 Fall:56(4):97-111. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0000000000000131. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27575761]

Nguyen KH, Patel BC, Tadi P. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Eye Retina. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194472]

Steel D. Retinal detachment. BMJ clinical evidence. 2014 Mar 3:2014():. pii: 0710. Epub 2014 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 24807890]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChang WC, Lin C, Lee CH, Sung TL, Tung TH, Liu JH. Vitrectomy with or without internal limiting membrane peeling for idiopathic epiretinal membrane: A meta-analysis. PloS one. 2017:12(6):e0179105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179105. Epub 2017 Jun 16 [PubMed PMID: 28622372]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMichalewska Z, Michalewski J, Adelman RA, Nawrocki J. Inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique for large macular holes. Ophthalmology. 2010 Oct:117(10):2018-25. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.02.011. Epub 2010 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 20541263]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFinn AP, Mahmoud TH. Internal Limiting Membrane Retracting Door for Myopic Macular Holes. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2019 Oct:39 Suppl 1():S92-S94. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001787. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28737535]

Grewal DS, Charles S, Parolini B, Kadonosono K, Mahmoud TH. Autologous Retinal Transplant for Refractory Macular Holes: Multicenter International Collaborative Study Group. Ophthalmology. 2019 Oct:126(10):1399-1408. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.01.027. Epub 2019 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 30711606]

Grewal DS, Mahmoud TH. Autologous Neurosensory Retinal Free Flap for Closure of Refractory Myopic Macular Holes. JAMA ophthalmology. 2016 Feb:134(2):229-30. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.5237. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26720054]

Chen CY, Hooper C, Chiu D, Chamberlain M, Karia N, Heriot WJ. Management of submacular hemorrhage with intravitreal injection of tissue plasminogen activator and expansile gas. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2007 Mar:27(3):321-8 [PubMed PMID: 17460587]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMartel JN, Mahmoud TH. Subretinal pneumatic displacement of subretinal hemorrhage. JAMA ophthalmology. 2013 Dec:131(12):1632-5. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.5464. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24337559]

Sharma S, Kumar JB, Kim JE, Thordsen J, Dayani P, Ober M, Mahmoud TH. Pneumatic Displacement of Submacular Hemorrhage with Subretinal Air and Tissue Plasminogen Activator: Initial United States Experience. Ophthalmology. Retina. 2018 Mar:2(3):180-186. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2017.07.012. Epub 2017 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 31047581]

Wood EH, Rao P, Mahmoud TH. Nanovitreoretinal Subretinal Gateway Device to Displace Submacular Hemorrhage: Access to the Subretinal Space Without Vitrectomy. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2022 Nov 1:42(11):2225-2228. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002669. Epub 2019 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 31688410]

Eide N, Walaas L. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy and other biopsies in suspected intraocular malignant disease: a review. Acta ophthalmologica. 2009 Sep:87(6):588-601. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01637.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19719804]

Stevenson KE, Hungerford J, Garner A. Local extraocular extension of retinoblastoma following intraocular surgery. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1989 Sep:73(9):739-42 [PubMed PMID: 2804029]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMohamed S, Claes C, Tsang CW. Review of Small Gauge Vitrectomy: Progress and Innovations. Journal of ophthalmology. 2017:2017():6285869. doi: 10.1155/2017/6285869. Epub 2017 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 28589037]

de Oliveira PR, Berger AR, Chow DR. Vitreoretinal instruments: vitrectomy cutters, endoillumination and wide-angle viewing systems. International journal of retina and vitreous. 2016:2():28 [PubMed PMID: 27980854]

Kuhn F, Aylward B. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a reappraisal of its pathophysiology and treatment. Ophthalmic research. 2014:51(1):15-31. doi: 10.1159/000355077. Epub 2013 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 24158005]

Durand ML. Bacterial and Fungal Endophthalmitis. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2017 Jul:30(3):597-613. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00113-16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28356323]

Sridhar J, Kasi S, Paul J, Shahlaee A, Rahimy E, Chiang A, Spirn MJ, Hsu J, Garg SJ. A PROSPECTIVE, RANDOMIZED TRIAL COMPARING PLAIN GUT TO POLYGLACTIN 910 (VICRYL) SUTURES FOR SCLEROTOMY CLOSURE AFTER 23-GAUGE PARS PLANA VITRECTOMY. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2018 Jun:38(6):1216-1219. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001684. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28492428]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMansouri MR, Tabatabaei SA, Soleimani M, Kiarudi MY, Molaei S, Rouzbahani M, Mireshghi M, Zaeferani M, Ghasempour M. Ocular trauma treated with pars plana vitrectomy: early outcome report. International journal of ophthalmology. 2016:9(5):738-42. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2016.05.18. Epub 2016 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 27275432]

Golnik KC, Law JC, Ramasamy K, Mahmoud TH, Okonkwo ON, Singh J, Arevalo JF. The Ophthalmology Surgical Competency Assessment Rubric for Vitrectomy. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2017 Sep:37(9):1797-1804. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001455. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28613227]