Introduction

The earliest description of a shoulder fracture was published in 1805 in P.J. Desault’s Treatise on Fractures and Luxations, and other affections of the bones.[1] Scapular fractures are uncommon, accounting for approximately 3-5% of all fractures of the shoulder girdle and less than 1% of total fractures. This is thought to be because they typically required high-energy trauma which also results in multi-system injuries[2]. Research shows that 80-95% of scapular fractures are associated with other injuries.[3] Because of the high energy needed to fracture the scapula and its association with other injuries, morbidity and mortality reports are relatively high.[4] However, emerging data has shown that scapular fractures with lower injury severity scores (ISS) do not carry the same associated increase in morbidity and mortality.[5] Treatment for scapular fractures was traditionally conservative with closed treatment; however, evaluation by an orthopedic trauma surgeon be the norm, as newer advancements in operative treatment have improved functional outcomes, and significant displacement is associated with poor long-term outcomes.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

As high as 80-90% of all scapular fractures occurred during high-energy trauma such as motor vehicle collisions, falls, and other high impact trauma.[6] Direct force may cause fractures of any region of the scapula while impaction of the humeral head into the glenoid fossa is often responsible for scapular neck and glenoid fractures. Motor vehicle collisions account for over 70% of scapular fractures, with 52% associated with drivers and 18% associated with pedestrians struck by motor vehicles.[6] Other reported mechanisms include electric shock and seizure because of forces on the scapula. Isolated scapular fractures are rare.[7]

Epidemiology

Scapular fractures account for approximately 0.4-1% of all fractures,[3] 3% of all fractures of the shoulder, and 5% of all fractures of the shoulder girdle.[8] Scapular fractures preferentially occur in young males (M: F = 6:49) between the ages of 25 and 50 years old and most often occur in the body or the glenoid.

- Body: 45%

- Glenoid Process: 35%

- Acromion: 8%

- Coracoid: 7%

Pathophysiology

Anatomy

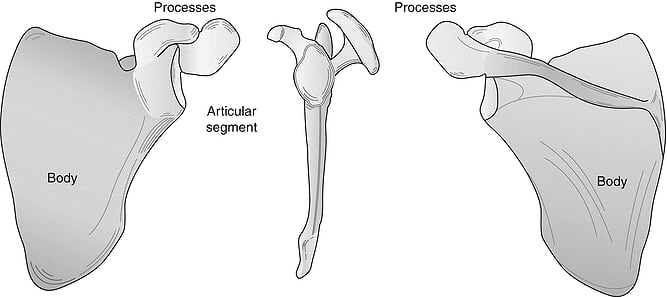

The scapula, more popularly known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the clavicle to the humerus. It is a triangular shape with four major processes: the spine, the acromion, the coracoid process, and the glenoid process: the scapula functions as the attachment site for 18 muscles which connected to the thorax, spine, and upper extremity. The scapula, besides the clavicle and humerus, provides rotational movement of the upper extremity and assist with abduction and rotation at the glenohumeral joint.[9]

Pathophysiology

Due to the force required to fracture of the scapula, there is a wide variety of fracture patterns reported. Fractures are classified based on the anatomical location on the scapula with fracture occurred. The Orthopedic Trauma Association has proposed a classification system at two levels: level 1 as a basic system for all trauma surgeons and level 2 for specialized shoulder surgeons. While this classification system is useful for classifying scapular fractures to identify the appropriate follow-up, no studies have correlated the grading system with prognosis.

History and Physical

The most common mechanism is blunt or penetrating trauma directly to the scapula. The physical exam and history can give the physician pertinent information and help rule out associated injuries that can be life-threatening. In a high energy trauma situation, depending on the patient's mental status this is not always possible. The physical exam of the shoulder and upper extremity should be performed in a matter that allows examination of the posterior forequarter. This can be difficult when the patient has multiple injuries and is supine in bed. Asymmetry of displacement of the shoulder or humeral head can be obvious or subtle. Palpation and visual examination of the bony landmarks should be performed followed by a thorough neurovascular examination of the upper extremity. Brachial plexus injuries can be associated with scapula fractures in 5-13 percent of patients. [10] Motor function can be difficult to assess secondary to pain associated with these injuries. A full assessment of the skin to look for open fractures is prudent because open fractures of the scapula require immediate irrigation and debridement in addition to antibiotics.

Evaluation

Because of the high energy needed to fracture the scapula, most patients found to have fractures of the scapula will have multiple other injuries. The patient should undergo evaluation as a trauma patient. However, there are specific potentially life-threatening injuries associated with scapular fractures that require assessment. For example, thoraco-scapular dissociations with disruptions of the subclavian vein and axillary vessels can lead to life-threatening hemorrhage.[11]

Diagnostic imaging should be performed to evaluate both scapular fractures and associated trauma. While conventional radiographs including an anterior-posterior, lateral, and axillary views are sufficient for evaluation of most scapular fractures, conventional radiography often misses associated injuries. Therefore, the recommendation is that a CT scan is performed in the evaluation of scapular fractures.[12] If there is a concern for the involvement of a joint, MRI may be needed to evaluate for ligamentous injury. 3D reconstruction of CT imaging may be helpful in determining management approaches and the need for surgical intervention.

Treatment / Management

Most scapular fractures are managed effectively with closed treatment and medical management. In minimally displaced fractures, which account for more than 90% of scapular fractures, management is with short-term immobilization in a sling and swath.[13] Patients should progress as quickly as possible to begin early range of motion exercises to prevent frozen shoulder as tolerated. (B3)

Scapular fractures themselves are rarely surgical emergencies, except for cases with thoracic penetration or dislocation causing rupture of nearby vascular structures. Fractures with significant displacement can cause long-term morbidity and poor outcomes of the shoulder which would be strong candidates for surgical techniques. Therefore, all scapular fracture should undergo evaluation for operative treatment.

Surgery is always recommended if there is a relevant alteration to the following:

- Scapula suspensory systems (SSSC; C4 linkage), "Floating Shoulder"

- Open Fracture

- Position integrity of the glenoid

- Lateral column displacement is present

Indications for open reduction and internal fixation are based on locations of fracture, displacement, angulation, and articular step-off.[14]

Intraarticular surgical indications:

- Articular step-off >5mm

- Associated glenohumeral instability

- Anterior rim fracture (>25% articular surface)

- Posterior rim fractures (>33% articular surface)

Extraarticular body and neck fractures surgical indications:

- Angular deformity (>40 degrees angulation)

- Lateral border offset (>15mm plus angular deformity >35 degrees)

- Lateral border offset (>20mm)

- Glenopolar angle (<22 degrees) on true Grashay AP

However, since scapular fractures are often associated with other high-energy trauma, any operative management of scapular fracture should be delayed until the patient is stable.

Differential Diagnosis

- Abdominal Pain in Elderly Persons

- Acromioclavicular Injury

- Fractures of Clavicle

- Mechanical Back Pain

- Pneumothorax

- Rib Fracture

- Shoulder Dislocation

Prognosis

Fractures found to be non-operative and managed conservatively have been shown to have good to excellent functional outcomes 86% of the time. Less than 1% of fractures require operative treatment, but studies demonstrate that operative patients have excellent functional outcomes.[15] Rehabilitation typically involves six weeks of the active and active-assisted range of motion; strength training begins approximately 3-4 months post injury or surgery. Patients can often expect virtually no functional deficits for non-operative fractures and good to excellent results in fractures requiring surgical intervention.

Pearls and Other Issues

1. Scapular fractures are usually the result of a significant force. Because of this, they often carry an association with other injuries.

Associated injuries include:

- Rib fractures

- Hips lateral lung injuries

- Injuries to the shoulder girdle complex

- Neurovascular injuries

- Suprascapular nerve injuries

- Vertebral compression fractures

2. The evaluation should include radiographic imaging and CT scan.

3. All scapular fractures should undergo evaluation by an orthopedic or trauma surgeon.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Since 1978, interprofessional teams have been identified by the World Health Organization as essential to high-quality care.[16] Given that scapular fractures typically occur in association with other traumatic injuries, highly competent, professional trauma teams deliver the needed care. Trauma teams will often comprise trauma surgeons, orthopedic traumatologists, emergency physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurses, physical therapy, occupational therapy, social work, and other specialized personnel. Effective communication and utilization of the skills of each of the members of the team result and higher quality care and better patient outcomes.[17]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Armstrong CP, Van der Spuy J. The fractured scapula: importance and management based on a series of 62 patients. Injury. 1984 Mar:15(5):324-9 [PubMed PMID: 6706394]

Ideberg R, Grevsten S, Larsson S. Epidemiology of scapular fractures. Incidence and classification of 338 fractures. Acta orthopaedica Scandinavica. 1995 Oct:66(5):395-7 [PubMed PMID: 7484114]

Baldwin KD, Ohman-Strickland P, Mehta S, Hume E. Scapula fractures: a marker for concomitant injury? A retrospective review of data in the National Trauma Database. The Journal of trauma. 2008 Aug:65(2):430-5. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31817fd928. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18695481]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBrown CV, Velmahos G, Wang D, Kennedy S, Demetriades D, Rhee P. Association of scapular fractures and blunt thoracic aortic injury: fact or fiction? The American surgeon. 2005 Jan:71(1):54-7 [PubMed PMID: 15757058]

Weening B, Walton C, Cole PA, Alanezi K, Hanson BP, Bhandari M. Lower mortality in patients with scapular fractures. The Journal of trauma. 2005 Dec:59(6):1477-81 [PubMed PMID: 16394925]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMcGahan JP, Rab GT, Dublin A. Fractures of the scapula. The Journal of trauma. 1980 Oct:20(10):880-3 [PubMed PMID: 6252325]

Tarquinio T, Weinstein ME, Virgilio RW. Bilateral scapular fractures from accidental electric shock. The Journal of trauma. 1979 Feb:19(2):132-3 [PubMed PMID: 762731]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcGinnis M, Denton JR. Fractures of the scapula: a retrospective study of 40 fractured scapulae. The Journal of trauma. 1989 Nov:29(11):1488-93 [PubMed PMID: 2685337]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCowan PT, Mudreac A, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Back, Scapula. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30285370]

Mayo KA, Benirschke SK, Mast JW. Displaced fractures of the glenoid fossa. Results of open reduction and internal fixation. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1998 Feb:(347):122-30 [PubMed PMID: 9520882]

Zelle BA, Pape HC, Gerich TG, Garapati R, Ceylan B, Krettek C. Functional outcome following scapulothoracic dissociation. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2004 Jan:86(1):2-8 [PubMed PMID: 14711938]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLantry JM, Roberts CS, Giannoudis PV. Operative treatment of scapular fractures: a systematic review. Injury. 2008 Mar:39(3):271-83 [PubMed PMID: 17919636]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVoleti PB, Namdari S, Mehta S. Fractures of the scapula. Advances in orthopedics. 2012:2012():903850. doi: 10.1155/2012/903850. Epub 2012 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 23209916]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCole PA, Freeman G, Dubin JR. Scapula fractures. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2013 Mar:6(1):79-87. doi: 10.1007/s12178-012-9151-x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23341034]

Zlowodzki M, Bhandari M, Zelle BA, Kregor PJ, Cole PA. Treatment of scapula fractures: systematic review of 520 fractures in 22 case series. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 2006 Mar:20(3):230-3 [PubMed PMID: 16648708]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGillam S. Is the declaration of Alma Ata still relevant to primary health care? BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2008 Mar 8:336(7643):536-8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39469.432118.AD. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18325964]

Courtenay M, Nancarrow S, Dawson D. Interprofessional teamwork in the trauma setting: a scoping review. Human resources for health. 2013 Nov 5:11():57. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-57. Epub 2013 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 24188523]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence