Introduction

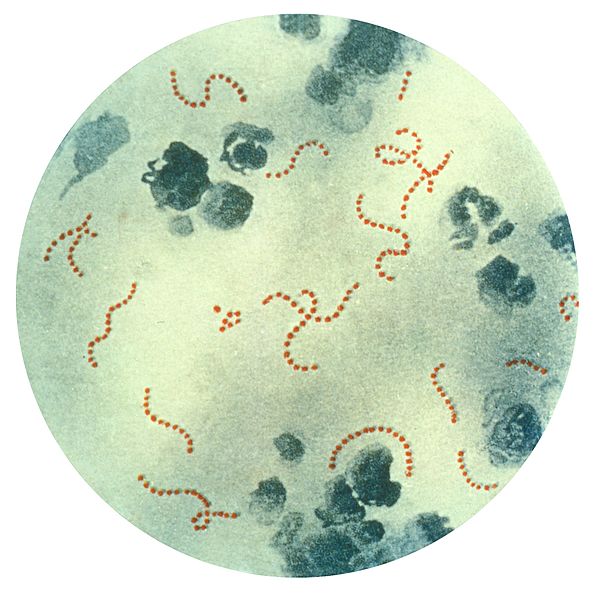

Group A Streptococcus (GAS) refers to the bacterial species "Streptococcus pyogenes," which is a gram-positive bacterium that grows in pairs and chains. GAS is ubiquitously found in nature and is uniquely adapted to humans. GAS is responsible for a wide range of infections affecting the upper respiratory tract and skin, ranging from mild and superficial to severe and invasive forms (iGAS) (see Image. Streptococcus pyogenes Bacterium).[1][2]

GAS infections are increasing globally, with high morbidity and mortality rates.[1][2] These infections can affect various areas of the body and can be categorized based on their location and depth. Examples include pharyngitis, scarlet fever, and impetigo (superficial keratin layer); cellulitis (subcutaneous tissue); erysipelas (superficial epidermis); and more severe conditions such as streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS), myositis and myonecrosis (muscle), and necrotizing fasciitis (NF; fascia).[3] In addition to causing infections, GAS can lead to immune-mediated sequelae, including acute rheumatic fever (ARF), post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN), and complications from immune-mediated processes, such as rheumatic heart disease (RHD).[4]

Although most cases of pharyngitis are viral, GAS is the leading bacterial cause of acute pharyngitis. GAS accounts for 5% to 15% of sore throat visits in adults and 20% to 30% in children presenting with pharyngitis.[5][6][7] Prompt diagnosis and treatment are essential to prevent ARF and other sequelae.[6] Established criteria, diagnostic methods, and guidelines for managing GAS pharyngitis are available that aim to ensure timely diagnosis and reduce the risk of suppurative complications, such as peritonsillar abscess, iGAS infections, nonimmune-mediated sequelae, and further transmission.[6][8][9]

Despite the availability of guidelines for diagnosing GAS pharyngitis, antibiotics are often overprescribed, leading to unnecessary exposure and contributing to antibiotic resistance. Antibiotic resistance has been reported in various antibiotics, including penicillin, which is first-line therapy.[10][11][12] Overprescription is driven by several factors, such as poor adherence to guidelines, challenges in accurately diagnosing GAS pharyngitis, misdiagnosing GAS carriage as an active infection, and pressure from patients and clinicians to prescribe antibiotics.[5][6][13] Clinicians must exercise caution and prescribe antibiotics only when necessary to minimize antibiotic pressure and reduce the risk of resistance development.[5][7][14]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

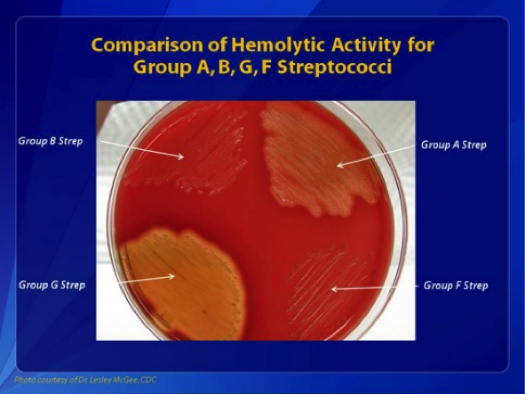

GAS is a gram-positive, nonspore-forming, catalase- and oxidase-negative bacterium that grows in pairs and chains.[15] When cultured on blood agar between 35 °C and 37 °C in a 10% carbon dioxide environment, GAS produces smooth, moist, grayish-white colonies with clear margins measuring over 0.5 mm. These colonies are surrounded by a zone of complete hemolysis (beta-hemolysis) (see Image. Comparisons of Hemolytic Activity of Groups A, B, G, and F Streptococci).

GAS is ubiquitous in nature and uniquely adapted to humans, with mucous membranes and skin serving as its only known reservoirs. GAS commonly causes a wide spectrum of infections in the upper respiratory tract and skin, ranging from mild and superficial to severe iGAS.[1][2] iGAS infections generally occur in normally sterile sites, such as the bloodstream, cerebrospinal fluid, or pleura. Globally, the incidence of GAS and iGAS infections is rising, contributing to significant morbidity and mortality.[1][2]

The Lancefield classification categorizes streptococci into serologic groups, labeled A to O, based on the reactions of antisera with carbohydrate antigens on the streptococcal cell wall.[16] At least 20 serological groups have been identified, such as groups A, B, and C, and GAS belongs to Lancefield group A.[17][18] Other streptococci from different Lancefield groups can cause similar syndromes to GAS. Notably, group B Streptococcus (GBS; S agalactiae) colonizes the human gastrointestinal and genital mucosa and can lead to conditions such as puerperal sepsis, neonatal infections, pneumonia, bacteremia, and meningitis.[19]

GAS has also been subdivided based on serotypes of M- and T antigens expressed on their surface.[16] Traditional serotyping methods to detect T- and M antigens have largely been replaced by sequence typing of the N-terminal part of the M-protein gene (emm), which is now primarily used for genotyping GAS, mainly for epidemiological purposes.[16][20] Whole genome sequencing (WGS) is increasingly utilized to identify epidemic strains of GAS. Over 220 emm types have been classified based on the gene sequence of the M-protein.[21][16] The streptococcal M-protein, a key virulence factor used for epidemiological typing, also serves as a potential vaccine antigen.[20]

Numerous virulence determinants in GAS have been identified, aiding in adhesion, colonization, evasion of the innate immune system, invasion, and dissemination within the host.[22] Key virulence factors include the M-protein, hyaluronic acid, streptokinase, and deoxyribonuclease (DNase)-B. Among its notable toxins are the pyrogenic toxins (also known as scarlatina or erythrogenic toxins), which are responsible for the rash in scarlet fever. These toxins also stimulate mononuclear cells to produce tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha and interleukins (IL-1 and IL-6), thereby contributing to fever and shock in patients with STSS.[1][23]

Certain bacterial superantigenic exotoxins, associated with syndromes such as STSS, trigger an atypical polyclonal activation of lymphocytes. This leads to rapid onset shock and multiorgan failure, contributing to high mortality. The primary superantigenic exotoxins identified are toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1) and enterotoxins.[23]

Epidemiology

GAS exclusively infects humans.[15] GAS spreads through respiratory secretions, fomites, and direct contact with infected skin (eg, in cases of impetigo). Although GAS infections can occur at any age, children, older adults, and immunocompromised individuals are at higher risk of becoming infected.[24] The incubation period for GAS is 2 to 5 days, during which patients are infectious and capable of transmitting the bacteria. Environmental factors and crowded settings—such as schools, households, and nursing homes—significantly increase transmission risk.[25] Notably, GAS can also cause disease in young, healthy individuals, with one study reporting its occurrence in 25% of people without identifiable risk factors.[25]

The epidemiology of GAS infections varies based on the type of infection. GAS can exist in the pharynx either as an asymptomatic carrier state or as a pathogen causing pharyngitis. Approximately 5% to 15% of individuals in the general population are estimated to be GAS carriers within populations. GAS pharyngitis is most common in children aged between 5 and 15 and represents the leading bacterial cause of acute pharyngitis in this group.[6] GAS accounts for 5% to 15% of sore throat visits in adults.[5][6][7] GAS pharyngitis usually occurs most frequently in the winter and early spring.[6] Pharyngitis caused by GAS typically results from person-to-person transmission through oropharyngeal secretions and respiratory droplets from infected individuals.[22][26]

Severe illness and iGAS infections exhibit a bimodal distribution, occurring most commonly in individuals aged 2 or younger and 50 or older.[26][27] Risk factors associated with increased mortality include advanced age, male sex, nursing home residency, chronic underlying conditions, immunosuppression, recent surgery, septic shock, necrotizing fasciitis, concurrent viral infections, isolated bacteremia, and infection with emm type 1 or 3.[25][27] The global prevalence of severe GAS infections is estimated at 18.1 million cases, with 1.78 million new cases and 616 million cases of GAS pharyngitis occurring annually.[28] Globally, severe GAS infections account for approximately 500,000 deaths annually, with RHD and iGAS infections being the leading contributors to these deaths.[28] The burden of iGAS is particularly high, with around 663,000 new cases and 163,000 deaths reported each year.[28]

Skin and soft tissue are the most common infection sites, with 32% of patients experiencing cellulitis and 8% developing necrotizing fasciitis.[25] Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) can vary from mild to invasive, with the latter associated with high mortality. Impetigo, a superficial infection typically caused by either Staphylococcus aureus or GAS, primarily affects young children and infants, especially those of preschool age. SSTIs are highly contagious, with a global prevalence estimated at 11.2%, higher in children (12.3%) compared to adults (4.9%).[29][30]

Cellulitis and erysipelas are skin infections caused by bacteria, including S aureus and GAS, and approximately 10% of the cases are caused by GAS alone. [31] Population-based surveillance data from Europe report an incidence rate of about 3 cases per 100,000 individuals per year, with no specific peak age or demographic for infection.[32] Population-based data in the United States estimate the rate of necrotizing fasciitis at 2.5 cases per 1,000,000 person-years.[33]

GAS is responsible for a wide range of infections and has historically been associated with increased morbidity and high mortality, particularly before the advent of antibiotics. Notably, puerperal sepsis and scarlet fever were major causes of death, with case fatality rates (CFR) reaching approximately 30% in the 19th century.[34] Infections related to iGAS continue to have high morbidity and mortality, with case fatality rates ranging from 10% to 30%.[35] Mortality for severe invasive infections, such as STSS and necrotizing fasciitis, has been reported in various studies to range from 14% to 64%, with some studies citing rates as high as 80%.[23][25][36]

A study in the United States examined iGAS data from 2005 to 2012 and reported case-fatality rates for septic shock, STSS, and necrotizing fasciitis at 45%, 38%, and 29%, respectively.[27] The number of iGAS infections began rising in the United States in the late 1980s.[27] The incidence remained stable from the mid-1990s until 2012, but it started to increase thereafter, with an average annual rate of 3.8 per 100,000 individuals from 2005 to 2012. Between 2014 and 2016, the incidence further rose from 4.8 to 5.8 per 100,000 individuals.[27]

Epidemiological surveillance is crucial for tracking epidemics, particularly given the increasing incidence and burden of GAS infections, especially iGAS, worldwide. WGS has an important role in this effort.[2][16][21][27][28] Since 2000, the dominant emm types in Europe and North America have been emm1 and emm3, with emm1 being the most prevalent type associated with invasive infections in high-income countries.[37] The 7 emm types responsible for 50% to 70% of iGAS infections include emm1, emm28, emm89, emm3, emm12, emm4, and emm6,[16][38] which are collectively referred to as M1global.

A new emm1 sublineage, coined M1UK, was identified in 2008 in the United Kingdom, which exhibited an increased expression of the scarlet fever toxin and streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin A (speA), leading to a rise in cases of scarlet fever and invasive infections in the United Kingdom between 2014 to 2018. As a result, it became the dominant type in the country.[39][40][41] Following the COVID-19 pandemic, 3 emerging M1UK clades rapidly expanded across the United Kingdom, resulting in severe outcomes in children.[37] All globally sequenced M1UK isolates (speA) can be traced back to the United Kingdom, where they caused an epidemic and have since spread across Europe and internationally.[37] Although declining immunity may contribute to streptococcal outbreaks, the genetic characteristics of M1UK suggest a fitness advantage in pathogenicity and a remarkable ability to endure population bottlenecks. M1UK is now the dominant strain in England. In addition, 2 other lineages—M113SNPs and M123SNPs—were also identified.[37][42]

Pathophysiology

GAS infections result from a complex interplay between host and bacterial factors that facilitate the establishment of infection. GAS utilizes various virulence factors, including toxins and other substances, to evade the host immune system and infect humans.[1] The hyaluronic acid capsule of GAS acts as a camouflage mechanism by resembling human hyaluronic acid, allowing the bacterium to evade immune detection. The surface-associated protein (S-protein) protects the bacterium from phagocytic destruction. Additionally, GAS produces proteases that degrade host immune signaling molecules and extracellular DNases to neutralize host immune defenses.[1]

Various surface substances, such as lipoteichoic acid and F-protein, enable GAS to adhere to host cells and facilitate colonization.[1] Cytolytic toxins, including streptolysins and hyaluronidase, contribute to tissue destruction, allowing GAS to invade the host.[1][43] Additionally, GAS has several factors, such as its capsule, G-protein, C5a peptidase, and M-protein, to evade host immune defenses. Among these, M-protein is particularly significant for GAS virulence, as it inhibits the phagocytosis of host immune cells.[44]

History and Physical

Obtaining a thorough history of the present illness and past medical history is crucial for patients presenting with symptoms of infection. GAS infections can present in diverse ways, influenced by factors such as the infection's location, the toxins produced, the invasiveness of the GAS strain, the patient's immune status, and whether the infection is superficial or deep. Clinicians must remain vigilant, as even mild-appearing infections can rapidly progress to severe conditions. For this reason, GAS should always be included in the differential diagnosis.

For instance, patients presenting with seemingly uncomplicated superficial SSTIs might have necrotizing fasciitis—a condition that demands immediate and aggressive treatment. To avoid missing such critical diagnoses, clinicians should perform thorough physical examinations and ask targeted questions. The severity of the condition may be more apparent in cases of GAS bacteremia or TSST-1. In these scenarios, clinicians should include GAS in the differential diagnosis, initiate appropriate antibiotic therapy, and obtain cultures. Each type of GAS infection presents distinct signs and symptoms, underscoring the need for clinicians to maintain a high level of suspicion to ensure accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

The most common symptoms of GAS pharyngitis are the sudden onset of fever and sore throat. Patients may also report headaches, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.[9] When obtaining a patient history, it is common to identify exposure to close contact with a GAS infection, particularly among school-age children or individuals in communal living environments, such as nursing homes, where prevalence is higher due to close living conditions.

Upon examination, physical findings in GAS pharyngitis commonly present with generalized inflammation of the tonsils and pharynx, variable tonsillar exudates, a red and swollen uvula, and palatal petechiae. Tender cervical lymphadenopathy is frequently noted during palpation.[9] Symptoms such as conjunctivitis, cough, coryza, or diarrhea are uncommon and, when present, are more suggestive of a viral etiology.[45] Physical examination of the posterior oropharynx alone is insufficient to differentiate GAS from other causes of acute pharyngitis, such as viral pharyngitis, which is the most common cause. The Centor Criteria, designed to diagnose GAS pharyngitis based on clinical findings, are unreliable when used alone and must be supported by microbiological testing for an accurate diagnosis.[9][46]

A thorough skin examination is essential, as the presence of a fine maculopapular erythematous rash along with a "strawberry tongue" strongly indicates scarlet fever. While scarlet fever is commonly associated with GAS streptococcal pharyngitis, it can also develop in cases of iGAS infections.[47] Impetigo typically occurs in school-aged children and is characterized by distinct cutaneous lesions described as discrete to confluent "honey-crusted" areas, most commonly on the face and extremities. Usually, vital sign abnormalities are not associated with the clinical presentation, and the patient will have no additional physical examination findings apart from the characteristic lesions.[29]

iGAS infections include necrotizing fasciitis, TSST-1, and any other infection affecting sterile body compartments. These infections are severe and require prompt treatment, as patients can deteriorate rapidly. Necrotizing fasciitis is a critical, life-threatening soft tissue infection that involves the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and fascia. This can resemble cellulitis, making it easy to misdiagnose. A key indicator of necrotizing fasciitis is pain that is disproportionate to the findings on physical examination, which is a common feature in these cases.[46] Clinicians must maintain a high level of suspicion, as misdiagnosis or delays in treatment can lead to poor outcomes. Prompt intervention with aggressive surgical debridement and antibiotic therapy is critical.[48]

STSS is a severe and life-threatening condition caused by GAS. This condition results from an iGAS infection where bacterial enterotoxins are released, leading to severe systemic symptoms. STSS often develops following a primary GAS infection, particularly in deep wound infections. Clinically, patients present with symptoms of severe sepsis, including tachycardia, hypotension, poor tissue perfusion, and signs of end-organ dysfunction.[32]

Evaluation

For individuals with GAS pharyngitis, throat swab cultures are the gold standard for identification. GAS grows easily on sheep blood agar and is catalase- and oxidase-negative. Confirmatory identification is achieved through Lancefield grouping and, more recently, techniques such as matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF).[15][49] However, culture results typically take 24 hours or longer, which delays critical information needed for treatment, isolation, and epidemiological purposes.

A rapid antigen detection test (RADT) can be used to diagnose GAS pharyngitis. The RADT has a sensitivity of approximately 85% in children, although variability exists, while its specificity is stable at 95%.[50] Due to the high specificity of the RADT in children, antibiotic therapy is recommended without the need for further throat culture to distinguish infection from carriage. If the RADT result is negative, treatment decisions depend on national guidelines.[50]

In the United States, however, in adults, due to the low general rate of GAS pharyngitis and corresponding low pretest probability, a negative RADT does not require confirmatory culture. A negative rapid swab result confers an extremely low post-test probability of GAS infection.[45][51] For other sites of infection, whether superficial or deep (such as skin, blood, wound, or lung), performing a Gram stain and cultures are the appropriate diagnostic methods. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can also be used to identify specific GAS strains, particularly in complicated cases.[52]

Treatment / Management

Recognizing GAS infections promptly and accurately can be challenging due to the broad differential diagnoses associated with its clinical manifestations. GAS can be associated with increased morbidity and ranks among the top 10 infectious causes of mortality.[53] GAS should always be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating patients, as it can lead to poor outcomes. Culture results are crucial for tailoring antibiotic therapy, and ensuring the initial empirical regimen covers GAS is essential.

Beta-lactam antibiotics are consistently effective against GAS and remain the preferred treatment for both noninvasive and iGAS infections. While reports of antibiotic resistance to penicillins and increased minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) to penicillin and cephalosporins have emerged—primarily due to mutations in the peptidoglycan synthetic enzyme pbp2x gene—resistance rates remain low.[54] However, penicillin continues to be the gold standard for GAS treatment.[55] For patients with penicillin allergies, macrolides (eg, erythromycin) and lincosamides (eg, clindamycin) are notable alternatives. However, resistance to these antibiotics has increased in the past decade, with variable prevalence of resistant GAS strains worldwide.[56](A1)

Reports from China indicate macrolide resistance rates as high as 90%, with resistance in some European countries ranging from 20% to 40% and lincosamide resistance reaching up to 19%; in other parts of Europe, these rates can be as low as 2%.[56][57] This resistance is attributed to multiple factors, including macrolide resistance mechanisms involving the MLSb phenotype.[56][57][58] Alternative antibiotics for penicillin-allergic patients can be considered if resistance to first-line agents is present. The choice of therapy should be guided by the location and severity of the infection, local antibiotic resistance patterns associated with GAS, and the patient's allergy profile. (A1)

More specifically, an oral antibiotic regimen is typically recommended for 10 days when treating GAS pharyngitis. Recommended regimens include penicillin V or amoxicillin for 10 days by mouth. An alternative treatment for GAS pharyngitis is a single intramuscular dose of penicillin G benzathine, particularly for patients who are unlikely to complete the full course of oral antibiotics.[45] For penicillin-allergic patients, alternatives such as macrolides or clindamycin can be used, but local resistance patterns should be considered when selecting treatment.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be initiated for severe GAS infections, such as necrotizing fasciitis and STSS, to ensure coverage while awaiting culture results.[32] For severe infections such as TSST-1 and necrotizing fasciitis, clindamycin is often added to the antibiotic regimen (eg, penicillin), as it can inhibit superantigen production, which enhances the phagocytosis of S pyogenes by reducing M-protein production.[59] In addition to antibiotics, supportive measures, such as intravenous fluid administration and blood pressure management with vasopressors, should be implemented for these severe or systemic infections.[60][61](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Many bacterial and viral pathogens can cause symptoms similar to those caused by GAS. Creating a differential diagnosis for each syndrome is crucial, as GAS can present in various forms, including pharyngitis, impetigo, cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, bacteremia, septic shock, and pneumonia. Therefore, it is crucial to consider GAS in the differential diagnosis of these symptoms to ensure appropriate antibiotic treatment and accurate testing for diagnosis.

Noninfectious conditions can closely resemble GAS infections, making a thorough physical examination essential. For instance, cellulitis can present similarly to venous stasis changes, with findings also overlapping those of acute deep vein thrombosis.[48]

Prognosis

Generally, simple, noninvasive GAS infections have low morbidity and mortality rates, with patients experiencing good outcomes. However, more invasive and severe GAS infections carry significant morbidity and mortality. iGAS infections caused by emm1 are associated with more severe conditions, such as TSST-1, and a higher risk of ICU admission compared to other iGAS strains.

TSST-1 has a mortality rate of 5% to 10%, particularly in patients at the extremes of age or those with preexisting conditions. High mortality rates are reported in patients with necrotizing fasciitis. When necrotizing fasciitis occurs alongside STSS, the mortality rate can reach up to 60%.[32][51]

Complications

GAS is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. In addition to causing infections, GAS can trigger immune-mediated sequelae, including ARF and PSGN, as well as direct consequences such as RHD.[4] The valvular damage caused by ARF can be permanent and, in severe cases, may necessitate surgical intervention, including valve repair or replacement.[62]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Isolation and prevention of exposure are crucial in limiting the spread of viral and bacterial infections, including GAS. This is particularly important for conditions such as impetigo and GAS pharyngitis, which are highly contagious through saliva, droplets, and skin contact. These infections are common among school-age children who have frequent close contact with peers. Therefore, isolating individuals with GAS infections is crucial by having them stay home from school, daycare, or work until they are no longer considered infectious. After 24 hours of antibiotic treatment, approximately 80% of patients are considered noninfectious.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Diagnosing and managing GAS infections requires an interprofessional healthcare team, including infectious disease specialists, microbiologists, nursing staff, and infectious disease pharmacists. One of the most crucial ways the healthcare team can improve patient outcomes is by promptly recognizing the signs of GAS infection, particularly in severe cases such as iGAS infections, necrotizing fasciitis, and TSST-1. Early detection and appropriate management are essential in improving patient outcomes.

Healthcare professionals must be able to recognize signs of sepsis and shock, carefully evaluating physical examination findings, systemic signs of infection, and potential pathological foci. Timely recognition and intervention can significantly improve clinical outcomes, as severe GAS infections demand prompt administration of antibiotics and additional treatments, such as surgery for necrotizing fasciitis or drainage of pleural effusion in GAS pneumonia. Effective management requires coordination among infectious disease specialists, clinicians, nursing staff, and pharmacists to ensure optimal care for these infections.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Streptococcus pyogenes Bacteria. This illustration depicts a photomicrograph of a specimen highlighting chain-linked S pyogenes bacteria.

Public Health Image Library, Public Domain, via Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Brouwer S, Rivera-Hernandez T, Curren BF, Harbison-Price N, De Oliveira DMP, Jespersen MG, Davies MR, Walker MJ. Pathogenesis, epidemiology and control of Group A Streptococcus infection. Nature reviews. Microbiology. 2023 Jul:21(7):431-447. doi: 10.1038/s41579-023-00865-7. Epub 2023 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 36894668]

Dunne EM, Hutton S, Peterson E, Blackstock AJ, Hahn CG, Turner K, Carter KK. Increasing Incidence of Invasive Group A Streptococcus Disease, Idaho, USA, 2008-2019. Emerging infectious diseases. 2022 Sep:28(9):1785-1795. doi: 10.3201/eid2809.212129. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35997313]

Ferretti JJ, Stevens DL, Fischetti VA, Stevens DL, Bryant AE. Streptococcus pyogenes Impetigo, Erysipelas, and Cellulitis. Streptococcus pyogenes: Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations. 2022 Oct 8:(): [PubMed PMID: 36479753]

Martin JM, Green M. Group A streptococcus. Seminars in pediatric infectious diseases. 2006 Jul:17(3):140-8 [PubMed PMID: 16934708]

Oliver J, Malliya Wadu E, Pierse N, Moreland NJ, Williamson DA, Baker MG. Group A Streptococcus pharyngitis and pharyngeal carriage: A meta-analysis. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2018 Mar:12(3):e0006335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006335. Epub 2018 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 29554121]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceShulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, Gerber MA, Kaplan EL, Lee G, Martin JM, Van Beneden C, Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2012 Nov 15:55(10):e86-102. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis629. Epub 2012 Sep 9 [PubMed PMID: 22965026]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCarville KS, Meagher N, Abo YN, Manski-Nankervis JA, Fielding J, Steer A, McVernon J, Price DJ. Burden of antimicrobial prescribing in primary care attributable to sore throat: a retrospective cohort study of patient record data. BMC primary care. 2024 Apr 17:25(1):117. doi: 10.1186/s12875-024-02371-y. Epub 2024 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 38632513]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWorrall G, Hutchinson J, Sherman G, Griffiths J. Diagnosing streptococcal sore throat in adults: randomized controlled trial of in-office aids. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 2007 Apr:53(4):666-71 [PubMed PMID: 17872717]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceShulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, Gerber MA, Kaplan EL, Lee G, Martin JM, Van Beneden C. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2012 Nov 15:55(10):1279-82. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis847. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23091044]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, Bartoces M, Enns EA, File TM Jr, Finkelstein JA, Gerber JS, Hyun DY, Linder JA, Lynfield R, Margolis DJ, May LS, Merenstein D, Metlay JP, Newland JG, Piccirillo JF, Roberts RM, Sanchez GV, Suda KJ, Thomas A, Woo TM, Zetts RM, Hicks LA. Prevalence of Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescriptions Among US Ambulatory Care Visits, 2010-2011. JAMA. 2016 May 3:315(17):1864-73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4151. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27139059]

Vannice KS, Ricaldi J, Nanduri S, Fang FC, Lynch JB, Bryson-Cahn C, Wright T, Duchin J, Kay M, Chochua S, Van Beneden CA, Beall B. Streptococcus pyogenes pbp2x Mutation Confers Reduced Susceptibility to β-Lactam Antibiotics. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2020 Jun 24:71(1):201-204. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1000. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31630171]

DeMuri GP, Sterkel AK, Kubica PA, Duster MN, Reed KD, Wald ER. Macrolide and Clindamycin Resistance in Group a Streptococci Isolated From Children With Pharyngitis. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2017 Mar:36(3):342-344. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001442. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27902646]

Shaikh N, Swaminathan N, Hooper EG. Accuracy and precision of the signs and symptoms of streptococcal pharyngitis in children: a systematic review. The Journal of pediatrics. 2012 Mar:160(3):487-493.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.09.011. Epub 2011 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 22048053]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMarston HD, Dixon DM, Knisely JM, Palmore TN, Fauci AS. Antimicrobial Resistance. JAMA. 2016 Sep 20:316(11):1193-1204. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11764. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27654605]

Gera K, McIver KS. Laboratory growth and maintenance of Streptococcus pyogenes (the Group A Streptococcus, GAS). Current protocols in microbiology. 2013 Oct 2:30():9D.2.1-9D.2.13. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc09d02s30. Epub 2013 Oct 2 [PubMed PMID: 24510893]

Gherardi G, Vitali LA, Creti R. Prevalent emm Types among Invasive GAS in Europe and North America since Year 2000. Frontiers in public health. 2018:6():59. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00059. Epub 2018 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 29662874]

van Sorge NM, Cole JN, Kuipers K, Henningham A, Aziz RK, Kasirer-Friede A, Lin L, Berends ETM, Davies MR, Dougan G, Zhang F, Dahesh S, Shaw L, Gin J, Cunningham M, Merriman JA, Hütter J, Lepenies B, Rooijakkers SHM, Malley R, Walker MJ, Shattil SJ, Schlievert PM, Choudhury B, Nizet V. The classical lancefield antigen of group a Streptococcus is a virulence determinant with implications for vaccine design. Cell host & microbe. 2014 Jun 11:15(6):729-740. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24922575]

Lancefield RC. THE ANTIGENIC COMPLEX OF STREPTOCOCCUS HAEMOLYTICUS : I. DEMONSTRATION OF A TYPE-SPECIFIC SUBSTANCE IN EXTRACTS OF STREPTOCOCCUS HAEMOLYTICUS. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1928 Jan 1:47(1):91-103 [PubMed PMID: 19869404]

Raabe VN, Shane AL. Group B Streptococcus (Streptococcus agalactiae). Microbiology spectrum. 2019 Mar:7(2):. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0007-2018doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.gpp3-0007-2018. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30900541]

Sanderson-Smith M, De Oliveira DM, Guglielmini J, McMillan DJ, Vu T, Holien JK, Henningham A, Steer AC, Bessen DE, Dale JB, Curtis N, Beall BW, Walker MJ, Parker MW, Carapetis JR, Van Melderen L, Sriprakash KS, Smeesters PR, M Protein Study Group. A systematic and functional classification of Streptococcus pyogenes that serves as a new tool for molecular typing and vaccine development. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2014 Oct 15:210(8):1325-38. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu260. Epub 2014 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 24799598]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTagini F, Aubert B, Troillet N, Pillonel T, Praz G, Crisinel PA, Prod'hom G, Asner S, Greub G. Importance of whole genome sequencing for the assessment of outbreaks in diagnostic laboratories: analysis of a case series of invasive Streptococcus pyogenes infections. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases : official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 2017 Jul:36(7):1173-1180. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-2905-z. Epub 2017 Jan 26 [PubMed PMID: 28124734]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWalker MJ, Barnett TC, McArthur JD, Cole JN, Gillen CM, Henningham A, Sriprakash KS, Sanderson-Smith ML, Nizet V. Disease manifestations and pathogenic mechanisms of Group A Streptococcus. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2014 Apr:27(2):264-301. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00101-13. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24696436]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAtchade E, De Tymowski C, Grall N, Tanaka S, Montravers P. Toxic Shock Syndrome: A Literature Review. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland). 2024 Jan 18:13(1):. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics13010096. Epub 2024 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 38247655]

Avire NJ, Whiley H, Ross K. A Review of Streptococcus pyogenes: Public Health Risk Factors, Prevention and Control. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland). 2021 Feb 22:10(2):. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10020248. Epub 2021 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 33671684]

Lamagni TL, Darenberg J, Luca-Harari B, Siljander T, Efstratiou A, Henriques-Normark B, Vuopio-Varkila J, Bouvet A, Creti R, Ekelund K, Koliou M, Reinert RR, Stathi A, Strakova L, Ungureanu V, Schalén C, Strep-EURO Study Group, Jasir A. Epidemiology of severe Streptococcus pyogenes disease in Europe. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2008 Jul:46(7):2359-67. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00422-08. Epub 2008 May 7 [PubMed PMID: 18463210]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceThompson KM, Sterkel AK, McBride JA, Corliss RF. The Shock of Strep: Rapid Deaths Due to Group a Streptococcus. Academic forensic pathology. 2018 Mar:8(1):136-149. doi: 10.23907/2018.010. Epub 2018 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 31240031]

Nelson GE, Pondo T, Toews KA, Farley MM, Lindegren ML, Lynfield R, Aragon D, Zansky SM, Watt JP, Cieslak PR, Angeles K, Harrison LH, Petit S, Beall B, Van Beneden CA. Epidemiology of Invasive Group A Streptococcal Infections in the United States, 2005-2012. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2016 Aug 15:63(4):478-86. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw248. Epub 2016 Apr 22 [PubMed PMID: 27105747]

Carapetis JR, Steer AC, Mulholland EK, Weber M. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. The Lancet. Infectious diseases. 2005 Nov:5(11):685-94 [PubMed PMID: 16253886]

Pereira LB. Impetigo - review. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2014 Mar-Apr:89(2):293-9 [PubMed PMID: 24770507]

Bowen AC, Mahé A, Hay RJ, Andrews RM, Steer AC, Tong SY, Carapetis JR. The Global Epidemiology of Impetigo: A Systematic Review of the Population Prevalence of Impetigo and Pyoderma. PloS one. 2015:10(8):e0136789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136789. Epub 2015 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 26317533]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBruun T, Oppegaard O, Kittang BR, Mylvaganam H, Langeland N, Skrede S. Etiology of Cellulitis and Clinical Prediction of Streptococcal Disease: A Prospective Study. Open forum infectious diseases. 2016 Jan:3(1):ofv181. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv181. Epub 2015 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 26734653]

Schmitz M, Roux X, Huttner B, Pugin J. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome in the intensive care unit. Annals of intensive care. 2018 Sep 17:8(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s13613-018-0438-y. Epub 2018 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 30225523]

Arif N, Yousfi S, Vinnard C. Deaths from necrotizing fasciitis in the United States, 2003-2013. Epidemiology and infection. 2016 Apr:144(6):1338-44. doi: 10.1017/S0950268815002745. Epub 2015 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 26548496]

Katz AR, Morens DM. Severe streptococcal infections in historical perspective. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 1992 Jan:14(1):298-307 [PubMed PMID: 1571445]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFactor SH, Levine OS, Schwartz B, Harrison LH, Farley MM, McGeer A, Schuchat A. Invasive group A streptococcal disease: risk factors for adults. Emerging infectious diseases. 2003 Aug:9(8):970-7 [PubMed PMID: 12967496]

Mehta S, McGeer A, Low DE, Hallett D, Bowman DJ, Grossman SL, Stewart TE. Morbidity and mortality of patients with invasive group A streptococcal infections admitted to the ICU. Chest. 2006 Dec:130(6):1679-86 [PubMed PMID: 17166982]

Vieira A, Wan Y, Ryan Y, Li HK, Guy RL, Papangeli M, Huse KK, Reeves LC, Soo VWC, Daniel R, Harley A, Broughton K, Dhami C, Ganner M, Ganner MA, Mumin Z, Razaei M, Rundberg E, Mammadov R, Mills EA, Sgro V, Mok KY, Didelot X, Croucher NJ, Jauneikaite E, Lamagni T, Brown CS, Coelho J, Sriskandan S. Rapid expansion and international spread of M1(UK) in the post-pandemic UK upsurge of Streptococcus pyogenes. Nature communications. 2024 May 10:15(1):3916. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-47929-7. Epub 2024 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 38729927]

Luca-Harari B, Darenberg J, Neal S, Siljander T, Strakova L, Tanna A, Creti R, Ekelund K, Koliou M, Tassios PT, van der Linden M, Straut M, Vuopio-Varkila J, Bouvet A, Efstratiou A, Schalén C, Henriques-Normark B, Strep-EURO Study Group, Jasir A. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of severe Streptococcus pyogenes disease in Europe. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2009 Apr:47(4):1155-65. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02155-08. Epub 2009 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 19158266]

Zhi X, Li HK, Li H, Loboda Z, Charles S, Vieira A, Huse K, Jauneikaite E, Reeves L, Mok KY, Coelho J, Lamagni T, Sriskandan S. Emerging Invasive Group A Streptococcus M1(UK) Lineage Detected by Allele-Specific PCR, England, 2020(1). Emerging infectious diseases. 2023 May:29(5):1007-1010. doi: 10.3201/eid2905.221887. Epub 2023 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 37019153]

Lamagni T, Guy R, Chand M, Henderson KL, Chalker V, Lewis J, Saliba V, Elliot AJ, Smith GE, Rushton S, Sheridan EA, Ramsay M, Johnson AP. Resurgence of scarlet fever in England, 2014-16: a population-based surveillance study. The Lancet. Infectious diseases. 2018 Feb:18(2):180-187. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30693-X. Epub 2017 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 29191628]

Lynskey NN, Jauneikaite E, Li HK, Zhi X, Turner CE, Mosavie M, Pearson M, Asai M, Lobkowicz L, Chow JY, Parkhill J, Lamagni T, Chalker VJ, Sriskandan S. Emergence of dominant toxigenic M1T1 Streptococcus pyogenes clone during increased scarlet fever activity in England: a population-based molecular epidemiological study. The Lancet. Infectious diseases. 2019 Nov:19(11):1209-1218. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30446-3. Epub 2019 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 31519541]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLi HK, Zhi X, Vieira A, Whitwell HJ, Schricker A, Jauneikaite E, Li H, Yosef A, Andrew I, Game L, Turner CE, Lamagni T, Coelho J, Sriskandan S. Characterization of emergent toxigenic M1(UK) Streptococcus pyogenes and associated sublineages. Microbial genomics. 2023 Apr:9(4):. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000994. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37093716]

Starr CR, Engleberg NC. Role of hyaluronidase in subcutaneous spread and growth of group A streptococcus. Infection and immunity. 2006 Jan:74(1):40-8 [PubMed PMID: 16368955]

Heath A, DiRita VJ, Barg NL, Engleberg NC. A two-component regulatory system, CsrR-CsrS, represses expression of three Streptococcus pyogenes virulence factors, hyaluronic acid capsule, streptolysin S, and pyrogenic exotoxin B. Infection and immunity. 1999 Oct:67(10):5298-305 [PubMed PMID: 10496909]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchroeder BM. Diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis. American family physician. 2003 Feb 15:67(4):880, 883-4 [PubMed PMID: 12613739]

Kanagasabai A, Evans C, Jones HE, Hay AD, Dawson S, Savović J, Elwenspoek MMC. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the accuracy of McIsaac and Centor score in patients presenting to secondary care with pharyngitis. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2024 Apr:30(4):445-452. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2023.12.025. Epub 2024 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 38182052]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHurst JR, Brouwer S, Walker MJ, McCormick JK. Streptococcal superantigens and the return of scarlet fever. PLoS pathogens. 2021 Dec:17(12):e1010097. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010097. Epub 2021 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 34969060]

Bellapianta JM, Ljungquist K, Tobin E, Uhl R. Necrotizing fasciitis. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2009 Mar:17(3):174-82 [PubMed PMID: 19264710]

Wang J, Zhou N, Xu B, Hao H, Kang L, Zheng Y, Jiang Y, Jiang H. Identification and cluster analysis of Streptococcus pyogenes by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. PloS one. 2012:7(11):e47152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047152. Epub 2012 Nov 7 [PubMed PMID: 23144803]

Cohen JF, Bertille N, Cohen R, Chalumeau M. Rapid antigen detection test for group A streptococcus in children with pharyngitis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016 Jul 4:7(7):CD010502. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010502.pub2. Epub 2016 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 27374000]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStevens DL. Streptococcal toxic-shock syndrome: spectrum of disease, pathogenesis, and new concepts in treatment. Emerging infectious diseases. 1995 Jul-Sep:1(3):69-78 [PubMed PMID: 8903167]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLiu D, Hollingshead S, Swiatlo E, Lawrence ML, Austin FW. Rapid identification of Streptococcus pyogenes with PCR primers from a putative transcriptional regulator gene. Research in microbiology. 2005 May:156(4):564-7 [PubMed PMID: 15862455]

Barnett TC, Bowen AC, Carapetis JR. The fall and rise of Group A Streptococcus diseases. Epidemiology and infection. 2018 Aug 15:147():e4. doi: 10.1017/S0950268818002285. Epub 2018 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 30109840]

Macris MH, Hartman N, Murray B, Klein RF, Roberts RB, Kaplan EL, Horn D, Zabriskie JB. Studies of the continuing susceptibility of group A streptococcal strains to penicillin during eight decades. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 1998 May:17(5):377-81 [PubMed PMID: 9613649]

Yu D, Zheng Y, Yang Y. Is There Emergence of β-Lactam Antibiotic-Resistant Streptococcus pyogenes in China? Infection and drug resistance. 2020:13():2323-2327. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S261975. Epub 2020 Jul 14 [PubMed PMID: 32765008]

Rafei R, Al Iaali R, Osman M, Dabboussi F, Hamze M. A global snapshot on the prevalent macrolide-resistant emm types of Group A Streptococcus worldwide, their phenotypes and their resistance marker genotypes during the last two decades: A systematic review. Infection, genetics and evolution : journal of molecular epidemiology and evolutionary genetics in infectious diseases. 2022 Apr:99():105258. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2022.105258. Epub 2022 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 35219865]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGergova R, Boyanov V, Muhtarova A, Alexandrova A. A Review of the Impact of Streptococcal Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance on Human Health. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland). 2024 Apr 15:13(4):. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics13040360. Epub 2024 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 38667036]

Sun L, Xiao Y, Huang W, Lai J, Lyu J, Ye B, Chen H, Gu B. Prevalence and identification of antibiotic-resistant scarlet fever group A Streptococcus strains in some paediatric cases at Shenzhen, China. Journal of global antimicrobial resistance. 2022 Sep:30():199-204. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2022.05.012. Epub 2022 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 35618209]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJohnson AF, LaRock CN. Antibiotic Treatment, Mechanisms for Failure, and Adjunctive Therapies for Infections by Group A Streptococcus. Frontiers in microbiology. 2021:12():760255. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.760255. Epub 2021 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 34803985]

Stevens DL. Invasive group A streptococcal disease. Infectious agents and disease. 1996 Jun:5(3):157-66 [PubMed PMID: 8805078]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStevens DL. Invasive group A streptococcus infections. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 1992 Jan:14(1):2-11 [PubMed PMID: 1571429]

Carapetis JR, Beaton A, Cunningham MW, Guilherme L, Karthikeyan G, Mayosi BM, Sable C, Steer A, Wilson N, Wyber R, Zühlke L. Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Nature reviews. Disease primers. 2016 Jan 14:2():15084. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.84. Epub 2016 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 27188830]