Introduction

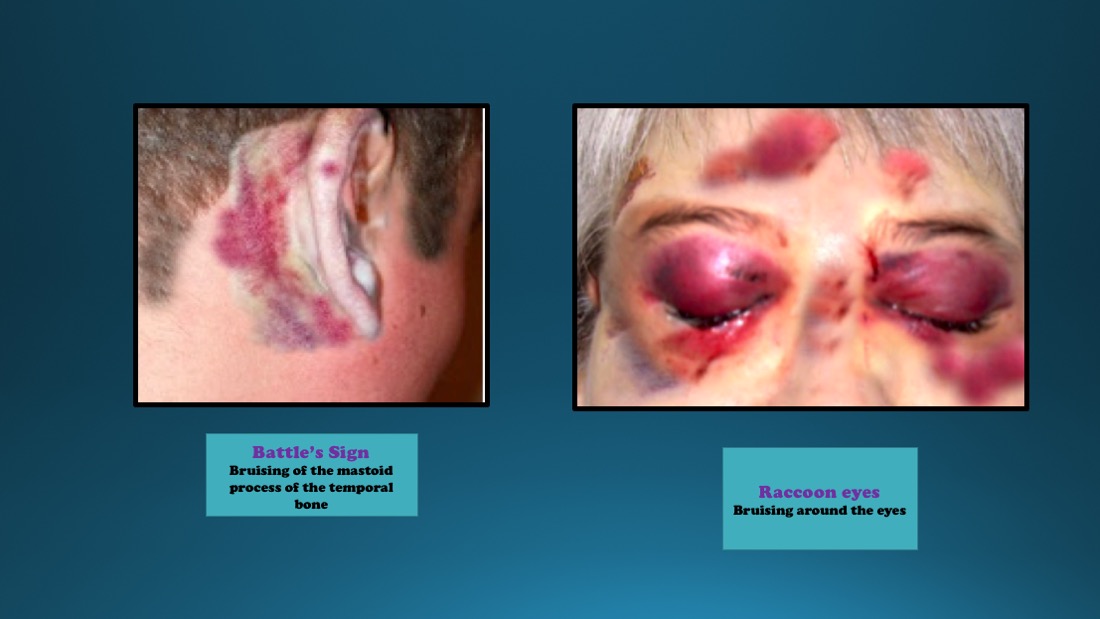

Basilar skull fractures, usually caused by substantial blunt force trauma, involve at least one of the bones that compose the base of the skull. Basilar skull fractures most commonly involve the temporal bones but may involve the occipital, sphenoid, ethmoid, and the orbital plate of the frontal bone as well. Several clinical exam findings highly predictive of basilar skull fractures include hemotympanum, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) otorrhea or rhinorrhea, Battle sign (retroauricular or mastoid ecchymosis), and raccoon eyes (periorbital ecchymosis). Basilar skull fractures are commonly associated with facial fractures, cervical spine injury, intracranial hemorrhage, cranial nerve injury, vascular injury, and meningitis.[1][2][3][2]

Basilar skull fractures are most commonly seen in younger people due to their propensity to do high-risk activities. The majority of basilar skull fractures are managed with conservative care.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Most basilar skull fractures are caused by high-velocity blunt trauma such as motor vehicle collisions, motorcycle crashes, and pedestrian injuries. Falls and assaults are also important causes. Penetrating injuries such as gunshot wounds account for less than 10% of cases.[4]

Epidemiology

Basilar skull fractures are relatively uncommon and are present in about 4% of all patients with a severe head injury. They represent 19% to 21% of skull fractures.[5]

Pathophysiology

The location of the fracture is predictive of associated injuries:

- Temporal fractures, which are most common, are associated with carotid injury, injury to cranial nerves VII or VIII, and mastoid cerebrospinal fluid leak.

- Anterior skull base fractures are associated with orbital injury, nasal cerebrospinal fluid leak, and injury to cranial nerve I.

- Central skull base fractures are associated with injury to cranial nerves III, IV, V or VI, and carotid injury.

- Posterior skull-based fractures are associated with a cervical spine injury, vertebral artery injury, and injury to the lower cranial nerves. These injuries are very serious and often the patients have hemiplegia or paraplegia

Associated injuries:

Basilar skull fractures are often associated with other central nervous systems (CNS) pathologies like epidural hematoma due to the weakness of the temporal bone and the close proximity of the middle meningeal artery.

At least 50% of basilar skull fractures are associated with another CNS injury and about 10% have cervical spine fracture.

The majority of basilar skull fractures involve the petrous bone, the external auditory canal, and tympanic membrane.

History and Physical

Clinical features of basilar skull fractures vary depending on the degree of the associated brain and cranial nerve injury.

Patients may present with altered mental status, nausea, and vomiting. Oculomotor deficits due to injuries to cranial nerves III, IV, and VI may be present. Patients may also present with facial droop due to compression or injury to cranial nerve VII. Hearing loss or tinnitus suggests damage to cranial nerve VIII.

Several clinical signs highly predictive of a basilar skull fracture include:

- Hemotympanum: Fractures that involve the petrous ridge of the temporal bone will cause blood to pool behind the tympanic membrane causing it to appear purple. This usually appears within hours of injury and may be the earliest clinical finding.

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea or otorrhea: “Halo” sign is the double ring pattern described when bloody fluid from the ear or nose containing CSF is dripped onto paper or linen. This sign is based on the principle of chromatography; components of a liquid mixture will separate when traveling through a material. This sign is not specific to the presence of CSF, as saline, tears or other liquids will also produce a ring pattern when mixed with blood. CSF leaks may be delayed hours to days after the initial trauma.

- Periorbital ecchymosis (raccoon eyes): Pooling of blood surrounding the eyes is most commonly associated with fractures of the anterior cranial fossa. This finding is typically not present during the initial evaluation and is delayed by 1 to 3 days. If bilateral, this finding is highly predictive of a basilar skull fracture.

- Retroauricular or mastoid ecchymosis (Battle sign): Pooled blood behind the ears in the mastoid region is associated with fractures to the middle cranial fossa. Like Raccoon eyes, this finding is frequently delayed by 1 to 3 days.

- Middle ear injury is seen in nearly one-third of patients and may present with hemotympanum, disruption of the ossicles, hearing loss, and even CSF leak.

- Other features include dizziness, tinnitus, and nystagmus

The presence of Battle sign and raccoon eye are highly predictive of basilar skull fracture.

Evaluation

The diagnosis may be obvious on a physical exam in some cases. Plain x-rays are not sensitive to detect basilar skull fracture.

The initial evaluation is usually via a non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan. Unfortunately, skull-based fractures that are linear or non-displaced may be difficult to detect. In patients where a high clinical suspicion for basilar skull fracture exists, multidetector CT (MDCT) thin-slice scanning through the face and skull base may aid in the detection of more subtle fractures. Conversely, the detailed small neural and vascular channels visualized on MDCT may be misread as fractures. Pneumocephalus should raise the suspicion for a basilar skull fracture. Further imaging with CT angiography and venography (CTA, CTV) to assess for vascular injury should be considered in the acute setting. MRI may be useful in assessing nerve injury and in evaluating for a cerebrospinal fluid leak.[6][7]

CSF leak is not easy to diagnose and the fluid should be sent for analysis of beta transferrin.

Treatment / Management

Basilar skull fractures are usually due to significant trauma. A thorough trauma evaluation with interventions to stabilize airway, ventilation, and circulatory issues is the priority. Associated cervical spine injury is common, so attention to cervical spine immobilization, particularly during airway management is necessary. Nasogastric tubes and nasotracheal intubation should be avoided because of the risk for inadvertent intracranial tube placement.[4][8][9](B2)

In addition, nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) should be avoided as it may induce pneumocephalus.

Patients with basilar skull fractures require admission for observation. Those taking anticoagulants should be admitted to a facility with immediate neurosurgical capabilities and the ability to do frequent assessments of the neurologic decline, even if no hemorrhage is present on initial imaging. Patients with intracranial hemorrhage require emergent neurosurgical evaluation. Otherwise, skull base fractures are often managed expectantly. Surgical management is necessary for cases complicated by intracranial bleeding requiring decompression, vascular injury, significant cranial nerve injury, or persistent cerebrospinal fluid leak.

Basilar skull fractures increase the risk of meningitis because of the increased possibility of bacteria from the paranasal sinuses, nasopharynx, and the ear canal making direct contact with the central nervous system. Patients with associated cerebrospinal fluid leaks, present in up to 45% of patients with basilar skull fractures, are often treated with prophylactic antibiotics to prevent meningitis, but there is no good evidence to support this practice. A recent Cochrane review did not find sufficient evidence to recommend prophylactic antibiotics in patients with basilar skull fractures even in the presence of a documented cerebrospinal fluid leak. However, patients with persistent leaks should have cerebrospinal fluid cultures to guide antibiotic therapy, and patients with clinical presentations consistent with meningitis should be treated with empiric antibiotics until culture results are available. While prophylactic antibiotics are not indicated generally, use is still considered appropriate for coverage related to procedures such as insertion of intracranial pressure (ICP) monitor. Persistent leaks require neurosurgical intervention. Less invasive, endoscopic techniques are becoming common with fewer of these injuries requiring open repair.[10]

Differential Diagnosis

The main differential diagnosis includes congenital maldevelopment of the skull bones and basal encephaloceles which can present with CSF leak.

Prognosis

The prognosis of skull base fractures depends on:

- The associated dural tear and CSF leak

- Instability

- Associated injuries

- Initial severity of neurologic and vascular injuries

The majority of CSF leaks resolve spontaneously within 5-10 days but some can persist for months. Meningitis may occur in less than 5% of patients but the risk increases with the duration of the CSF leak.

Conductive hearing loss usually resolves within 7-21 days.

Complications

- CSF leak

- Meningitis

- Cranial nerve palsies

- Hearing loss

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis

- Vertigo

- Intracranial hemorrhage

- Death

Cranial nerve deficits involve loss of smell and facial palsy.

Basilar skull fractures can also be associated with a vascular injury resulting in occlusion, fistula formation, bleeding, or pseudoaneurysm formation.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The patient with CSF rhinorrhea, if conservatively managed should be advised not to strain and blow the nostrils. Also, the patient should report early if he/she develops a headache and fever.

Pearls and Other Issues

Complications associated with basilar skull fractures include:

- Cerebrospinal fluid leak/fistula

- Meningitis

- Pneumocephalus

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis

- Carotid dissection, pseudoaneurysm or thrombosis

- Carotid-cavernous fistula

- Injury to cranial nerves III, IV, VI, VII and VIII

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Skull base fractures are not common but when they do occur, they represent a serious life-threatening condition with very high morbidity and mortality. Because of the diverse presentation, these patients are best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a neurosurgeon, neurologist, ophthalmologist, ENT surgeon, neurosurgical nurses, a radiologist, and an infectious disease specialist.

The patients are usually managed in an ICU setting and monitored by a nurse. Patients need frequent assessment of neurological signs, ventilation, and oxygenation. Nurses have to ensure that patients have DVT and gastric ulcer prophylaxis. Some patients may not be able to eat and parenteral nutrition may be required. The pharmacist needs to make sure that the patient is not receiving high doses of analgesias because this may hide any neurological signs. Further, the use of opiates may make it difficult to assess the pupils for elevation in intracranial pressure. The patient needs to be monitored by critical care nurses to ensure that there are no signs of CNS infection. The entire team must communicate regarding changes in the patient's condition to ensure that the patient is receiving the appropriate care. Outcomes will be improved by an interprofessional approach to the care of patients with a basilar skull fracture. [Level V]

Outcomes

The outcome of patients with basilar skull fractures depends on whether the fracture is displaced. For nondisplaced fractures, the management is conservative and the outcomes are good. However, for those with displaced fractures, intervention may be required and this also carries a risk of surgical complications. The key morbidity is meningitis which can be lethal. Those who have a dissection of the carotid artery can develop life-threatening bleeding. Overall, most patients with basilar skull fractures do have some type of residual functional or neurological deficit which may take months or even years to reverse.[11][12]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Solai CA, Domingues CA, Nogueira LS, de Sousa RMC. Clinical Signs of Basilar Skull Fracture and Their Predictive Value in Diagnosis of This Injury. Journal of trauma nursing : the official journal of the Society of Trauma Nurses. 2018 Sep/Oct:25(5):301-306. doi: 10.1097/JTN.0000000000000392. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30216260]

Harvell BJ, Helmer SD, Ward JG, Ablah E, Grundmeyer R, Haan JM. Head CT Guidelines Following Concussion among the Youngest Trauma Patients: Can We Limit Radiation Exposure Following Traumatic Brain Injury? Kansas journal of medicine. 2018 May:11(2):1-17 [PubMed PMID: 29796153]

Becker A, Metheny H, Trotter B. Battle Sign. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725789]

Wang H,Zhou Y,Liu J,Ou L,Han J,Xiang L, Traumatic skull fractures in children and adolescents: A retrospective observational study. Injury. 2018 Feb [PubMed PMID: 29203200]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePotapov AA, Gavrilov AG, Kravchuk AD, Likhterman LB, Kornienko VN, Arutiunov NV, Gaĭtur EI, Fomichev DV. [Basilar skull fractures: clinical and prognostic aspects]. Zhurnal voprosy neirokhirurgii imeni N. N. Burdenko. 2004 Jul-Sep:(3):17-23; discussion 23-4 [PubMed PMID: 15490634]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJohnston JJ. The Galasko report implemented: the role of emergency medicine in the management of head injuries. European journal of emergency medicine : official journal of the European Society for Emergency Medicine. 2007 Jun:14(3):130-3 [PubMed PMID: 17473605]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSchunk JE, Rodgerson JD, Woodward GA. The utility of head computed tomographic scanning in pediatric patients with normal neurologic examination in the emergency department. Pediatric emergency care. 1996 Jun:12(3):160-5 [PubMed PMID: 8806136]

Phang SY, Whitehouse K, Lee L, Khalil H, McArdle P, Whitfield PC. Management of CSF leak in base of skull fractures in adults. British journal of neurosurgery. 2016 Dec:30(6):596-604 [PubMed PMID: 27666293]

Tunik MG, Powell EC, Mahajan P, Schunk JE, Jacobs E, Miskin M, Zuspan SJ, Wootton-Gorges S, Atabaki SM, Hoyle JD Jr, Holmes JF Jr, Dayan PS, Kuppermann N, Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN). Clinical Presentations and Outcomes of Children With Basilar Skull Fractures After Blunt Head Trauma. Annals of emergency medicine. 2016 Oct:68(4):431-440.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.04.058. Epub 2016 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 27471139]

Lin DT, Lin AC. Surgical treatment of traumatic injuries of the cranial base. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2013 Oct:46(5):749-57. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2013.06.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24138735]

Leibu S, Rosenthal G, Shoshan Y, Benifla M. Clinical Significance of Long-Term Follow-Up of Children with Posttraumatic Skull Base Fracture. World neurosurgery. 2017 Jul:103():315-321. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.04.068. Epub 2017 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 28433849]

McCutcheon BA, Orosco RK, Chang DC, Salazar FR, Talamini MA, Maturo S, Magit A. Outcomes of isolated basilar skull fracture: readmission, meningitis, and cerebrospinal fluid leak. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2013 Dec:149(6):931-9. doi: 10.1177/0194599813508539. Epub 2013 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 24135209]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRatilal BO, Costa J, Pappamikail L, Sampaio C. Antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing meningitis in patients with basilar skull fractures. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2015 Apr 28:2015(4):CD004884. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004884.pub4. Epub 2015 Apr 28 [PubMed PMID: 25918919]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOzaki A, Iwata T, Terada E, Kajikawa R, Tsuzuki T, Kishima H. Severe Delayed-Onset Meningitis Developed One Year After a Basilar Skull Fracture Without a Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak: A Case Report. Cureus. 2024 Dec:16(12):e75261. doi: 10.7759/cureus.75261. Epub 2024 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 39764347]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence