Introduction

Although encountered in clinical practice for the past 4 to 5 decades, hypertension in neonates has been relatively recently recognized and investigated as a distinct neonatal morbidity. The evaluation and management of the disease process were earlier compromised by a lack of comprehensive normative data for neonatal blood pressure (BP) due to the unavailability of accurate invasive or non-invasive techniques for its measurement. The significant and rapid variability in the BP with gestational age, postnatal age, birth weight, and gender in the referred population posed further challenges in establishing normal values and an inclusive definition of neonatal hypertension (NH).

The clinical course, outcomes, and long-term sequelae of NH are still incompletely understood, and there is a lack of consensus among the experts about the use and selection of antihypertensive drugs for its treatment.[1] This topic reviews the current information regarding the definition, risk factors, etiopathogenesis, and management of hypertension in newborn infants.

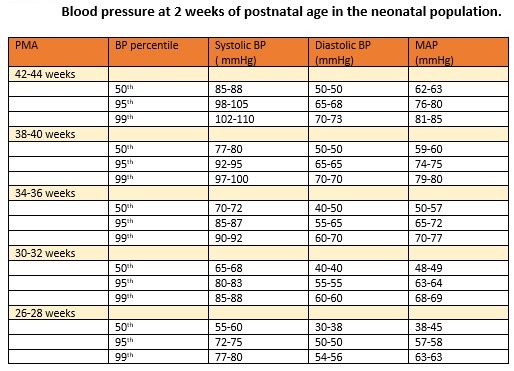

NH is diagnosed when the systolic or diastolic BP (DBP) values, as measured on 3 separate occasions, are over or equal to the 95th percentile for the infant's post-conceptual age.[2] A systolic BP (SBP) over the 99th percentile suggests severe hypertension and indicates the need to initiate antihypertensive therapy and specific investigations to identify the etiopathogenesis. The normative data for BP in the neonates are presented in the table (see Table. Blood Pressure at 2 Weeks of Postnatal Age in the Neonatal Population).[3]

Table 1. Normative data for blood pressure at 2 weeks of postnatal age in the neonatal population.

(Adapted from reference number 11, Dione et al, Peds Nephro,2012;27:159-60)

Measurement Of Blood Pressure

BP can be measured via invasive or non-invasive methods.

Invasive Method

The invasive intra-arterial blood pressure measurement and continuous monitoring, regarded as the gold standards, are done by utilizing an indwelling catheter in 1 of the umbilical, radial, or posterior tibial arteries, which is connected to a pressure transducer and via that to the multichannel display patient monitor. This method is generally reserved for sick and unstable infants and for those who are extremely premature.[4]

The following steps and precautions should be taken while measuring the blood pressure intra-arterially via the transducer.

- The transducer should be positioned at the level of the heart.

- There should be no air bubbles in the tube, as their presence might increase DBP and decrease SBP.

- A dicrotic notch should be seen on the arterial waveform.

- Tubing should be of low compliance and the smallest acceptable length, as increasing the length falsely decreases the values.

- The pressure transducer should be the reference point at zero atmospheric pressure.

- The transducer should be irrigated with a continuous heparin infusion.

- The umbilical catheter should be of appropriate size. A narrow catheter falsely decreases the SBP.

- The umbilical artery catheter should be removed, preferably after 5 to 7 days, as prolonged catheterization may increase the risk of thrombus formation, leading to false readings.

Non-invasive Methods

Automated oscillometry is the commonest and most widely used non-invasive method for measuring blood pressure in the neonatal intensive care unit. This device detects the maximum blood pressure oscillations from the arterial blood flow as mean blood pressure (MBP), which is then converted into the projected systolic and diastolic BP using standard proprietary algorithms. The oscillometric BP measurements generally correlate well with the invasive intra-arterial readings. However, it may overestimate the intra-arterial SBP values by 3 to 8 mm Hg, thereupon over-diagnosing hypertension, and become inaccurate when MAP drops below 30 mm Hg, thus missing hypotension. The device may also underestimate SBP in small for gestational age infants.

For accuracy, the optimum cuff width is suggested to be in a ratio of 0.45 to 0.70, with the arm circumference covering 80% of the arm's length, and the size should be standardized for uniformity in the results. The BP becomes erroneously high if the cuff size is too small. At the time of measurement, the infant should lie supine, quietly awake, calm, preferably sleeping, and about 1 to 1.5 hours postprandial. At least 3 readings, 2 minutes apart, should be taken in the right arm as the preferred site. Using a sphygmomanometer is not recommended because the Korotkoff sounds are not loud enough to be reliably audible in this age group of infants.[5] Ultrasound Doppler is rarely used as a regular BP monitoring device as it can underestimate the SBP values.[6]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

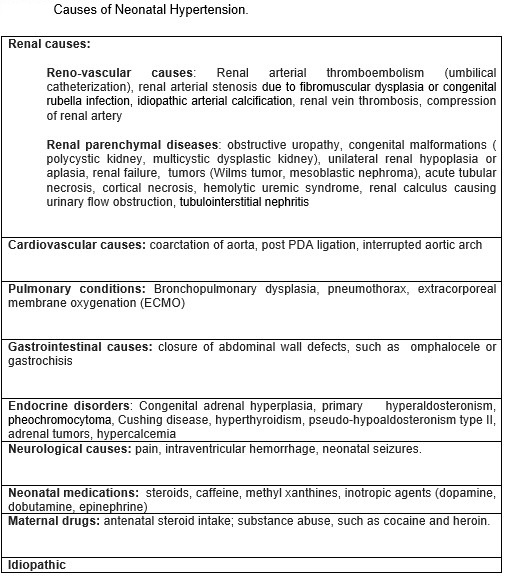

Prematurity is a risk factor, and 75% of all infants with NH are born preterm.[7] Newborns suffering from NH are generally sicker and have higher neonatal illness scores and extended NICU stays. The most common causes of significant hypertension requiring medication in neonates are respiratory illnesses (BPD), drugs (caffeine, dexamethasone), ECMO, and renal disorders (parenchymal, reno-vascular, acute renal tubular necrosis, renal failure). Other etiological factors may be neurological (seizures), endocrinal, cardiac- mainly coarctation of the aorta or infrequently PDA, and umbilical artery catheter-related thromboembolism.[8]

BPD is an independent risk factor for NH and the most significant non-renal cause of hypertension in VLBW infants.[9][10] Premature infants with intraventricular hemorrhage may be at risk for NH. Case reports of a term infant with ductal aneurysm have been recently published. Other anecdotally reported rare causes are adrenal hemorrhage, vitamin D toxicity with renal calcinosis, and total parenteral nutrition. Almost 57 % of the cases of NH do not have identifiable causes and are categorized as idiopathic (See Table. Causes of Neonatal Hypertension).[8][11]

Epidemiology

The incidence of neonatal hypertension is reported to be 0.2% in term newborn infants and up to 3% in the infants admitted to the NICU.[3] The variation in the incidence may be attributed to the differences in the study population and the definition of NH used for the study. It is reported that 1.4% of preterm infants require antihypertensive therapy during their NICU stay compared to 1% in term infants.[9]

The incidence of NH is demonstrated to be 13% to 43% in infants with BPD. The exact prevalence of NH in the preterm population has not been determined.

Pathophysiology

A reno-vascular mechanism is the commonest pathway and is operative in most conditions leading to NH. Systemic causes that might decrease renal perfusion vary. Catheterization of the umbilical artery causes endothelial cell injury and the formation of thrombi in the renal vessels. The resultant decrease in kidney perfusion activates the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAS), thus causing hypertension.[12]

An inability to excrete free water and an increase in serum aldosterone levels have been reported in BPD, which might contribute to systemic hypertension. An increase in peripheral arterial wall thickness and abnormal vasomotor functions have recently been demonstrated as the etiopathogenesis for NH in infants with BPD.[10][13]

Infants of diabetic mothers or those with Factor V Leiden mutation may present with renal vein thrombosis (RVT) and decreased renal perfusion. Neonatal asphyxia may result in renal tubular necrosis (ATN) and secondary to that in NH. Neonatal tumors, such as pheochromocytoma, neuroblastoma, Wilms tumor, and mesoblastic nephroma, can cause NH by compressing the renal vessels or ureters or by producing vasoactive substances, such as catecholamines. COA and PDA lead to decreased forward blood flow, diminished renal perfusion, and the activation of RAS. Closing abdominal wall defects increases intraabdominal pressure that may compress renal vessels. Hypertension in ECMO is thought to be secondary to the increased stroke volume caused by the increased aortic return from ECMO pump blood and to be caused by abnormal sodium or water handling in response to the non-pulsatile arterial flow through the infants’ systems.

History and Physical

The neonates suffering from NH are usually asymptomatic, and the hypertension is detected via routine continuous BP monitoring in the NICU. Those who are symptomatic may present with feeding intolerance, poor nipple efforts, irritability, hypotonia, hypertonia, vomiting, apnea, respiratory distress, oxygen desaturations, and in severe cases, tachycardia, congestive heart failure, cardiogenic shock, and seizures. The symptoms are non-specific and varied. In older and term newborns, it is either detected by routine monitoring in the NICU or by checking vital signs during well-child visits. The newborns who are discharged from the nursery may return with symptoms of irritability and failure to thrive.[14]

A detailed system-wise physical examination is important. The general appearance may reveal dysmorphism, consistent with Turner, William’s, or Noonan syndromes, the diseases associated with coarctation of the aorta. The presence of a cardiac murmur with a discrepancy in the 4 limb blood pressures and femoral pulses suggests COA. Physical features of congestive heart failure like tachycardia, murmur, mottling, and cyanosis may be present. Palpation of the abdomen may reveal a mass in conditions of polycystic kidney disease, renal tumors, hydronephrosis, and renal vein thrombosis. The genitourinary examination may reveal congenital anomalies or ambiguous genitalia in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. The history of oligohydramnios may suggest congenital renal anomalies, and the infant may be born with typical features in severe cases.

Evaluation

A thorough maternal and perinatal history and physical examination guide in identifying the potential etiology. As the reno-vascular or renal parenchymal disorders account for most cases of NH, the initial investigations pertain to this system and include urine analysis, blood urea nitrogen level, and serum values of creatinine, electrolytes, and calcium. The urine should be tested for vanillyl mandelic acid and homovanillic acid. The initial workup should include aortic and renal ultrasonography with a Doppler study.[8]

Further investigation is guided by history and clinical suspicion and should include the following:

- Thyroid function tests, cortisol levels, aldosterone and plasma renin activity, plasma and urine catecholamines and metanephrines, serum 11 dexoycortisol, and 11 deoxycorticosterone. Urinary 17-hydroxysteroid and 17-ketosteroid

- Additional studies include a chest radiograph (BPD, congestive heart failure), an echocardiogram, a voiding cystourethrogram, captopril renal scintigraphy, a dimercaptosuccinic acid renal scan, computed tomographic angiography to evaluate the renal artery and the aorta, abdominal MRI, and head ultrasonography to rule out intraventricular hemorrhage.

Treatment / Management

In most infants with NH, treating the correctable causes usually resolves the condition. The umbilical catheter should be removed as soon as possible. Hypercalcemia or excessive fluid intake should be corrected with fluid restriction or diuretics. Doses of medications like inotropes, steroids, or caffeine should be adjusted or the drug discontinued. Surgical conditions should be addressed as needed. Analgesia may be considered for the relief of pain. Appropriate hormonal therapy should be administered for endocrinal disorders. If hypertension persists above the 99th percentile of the normative data despite these measures, antihypertensive therapy should be initiated.[15](A1)

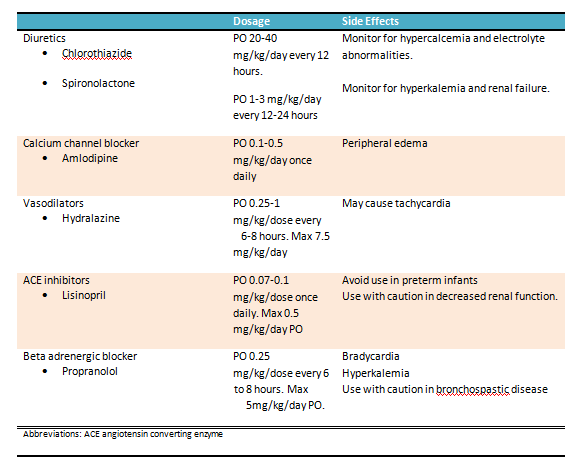

Mild hypertension: These infants can be regularly monitored and closely observed. If hypertension does not resolve spontaneously, then it can be treated with a thiazide (preferred) or a loop diuretic agent.

Moderate hypertension: These infants have blood pressure readings between the 95th and 99th percentiles for their age without signs of end-organ involvement. They can be treated with diuretics (first line), hydralazine, or propranolol. There is a paucity of information regarding the indications and benefits of oral antihypertensive agents for mild to moderate hypertension in neonates. The details of the commonly used oral agents are presented in the table. See Table. Oral Treatment Options for Hypertension in the Neonatal Age Group.

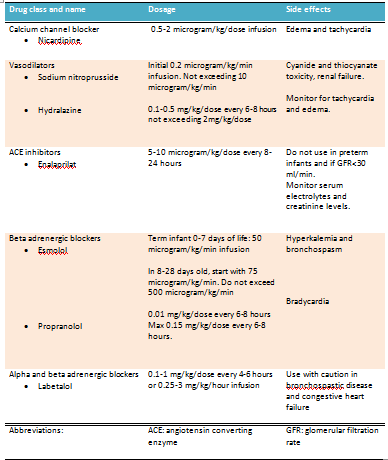

Severe hypertension: If the blood pressure is greater than the 99 percentile, treatment with continuous intravenous drug infusion is warranted. A rapid reduction in blood pressure should be avoided. Close blood pressure monitoring with an intra-arterial catheter is preferred in these patients. The recommended IV antihypertensive agents and their doses and side effects are presented in the table (see Table. Intravenous Treatment Options for Hypertension in the Neonatal Age Group).

Surgical intervention in the management of neonatal HT is indicated under conditions such as coarctation of the aorta, renal artery or vein occlusion, urinary tract or ureteropelvic junction obstruction, polycystic kidney disease, neuroblastoma, or Wilms tumor, among others.[16]

Differential Diagnosis

NH is a manifestation of specific disorders of various organ systems. The etiopathogenic disease entities leading to NH should be differentiated by appropriate investigations. As the clinical presentation of NH, with symptoms like respiratory distress, hypotonia, irritability, feeding intolerance, and tachycardia, among others, is nonspecific, all other neonatal causes for such symptoms should be ruled out.

Prognosis

The outcome of NH depends on the etiology and severity of the condition. NH associated with renal venous thrombosis, umbilical catheterization, or acute renal tubular necrosis are transient and resolve as the underlying disorder ameliorates. The presence of end-organ damage is associated with poor prognosis. Most newborns generally require drug therapy for a short period, and long-term therapy is infrequently needed. A retrospective study reported that only 15 percent of the 40 percent of infants discharged from the hospital on antihypertensive medication required treatment by 3 to 6 months.[2]

The natural history of NH is different from that of hypertension in older children. A study that included 700 infants reported that the median duration of therapy with antihypertensive drugs in infants in the NICU was 10 days. Infants suffering from hypertension due to BPD are usually found to have their BP normalized on follow-up examinations.[17] NH, due to underlying renal parenchymal diseases, may have persisting hypertension into childhood and require prolonged therapy.

Complications

Infants with untreated severe unrelenting hypertension may develop multiple end-organ damages and suffer from vascular injury, left ventricular hypertrophy, encephalopathy, and hypertensive retinopathy. Early, aggressive, and effective treatment should be provided in such conditions. Common complications of longstanding and severe hypertension are hypertensive nephropathy with variable renal dysfunction and hypertensive cardiomyopathy with left ventricular hypertrophy, dilation, or dysfunction. The long-term adverse effects and sequelae of untreated as compared to treated hypertension in infants are unknown. Recent epidemiological evidence suggests that childhood hypertension is associated with a higher risk for adulthood hypertension.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Neonatal hypertension is often missed or undiagnosed in infants admitted to the newborn nursery and is picked up incidentally on routine follow-up visits. Early diagnosis and timely treatment are important in this population to prevent end-organ damage and adverse long-term sequelae. Pharmacological management is challenging for neonatologists as very few agents have been studied for efficacy and safety in this age group. A lack of normative data and definition adds to the uncertainties in managing hypertension presenting during the neonatal period and infancy.

There are no clear-cut guidelines, especially about the timing of starting antihypertensive treatment and the management of milder forms. As most infants require short-term therapy (10 days on average) and many ameliorate spontaneously with time, a judicious approach based on the infant's condition and other associated factors should be considered. In moderate NH, starting treatment with oral and introducing IV therapy is recommended, and in severe NH, starting treatment with oral is recommended.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of NH requires a multi-disciplinary approach with a team that includes the primary care pediatrician, neonatologist, pediatric nephrologist, and cardiologist. The prognosis depends on the cause and the presence of end-organ dysfunction. To improve the outcomes, prompt recognition and management by specialists are suggested. The American Academy of Pediatrics does not recommend routine screening of children for hypertension until 3 years of age. However, children with identifiable risk factors for hypertension and those suspected of the morbidity based on history and presenting symptoms should be investigated and appropriately managed.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Adelman RD. Neonatal hypertension. Pediatric clinics of North America. 1978 Feb:25(1):99-110 [PubMed PMID: 628572]

Seliem WA, Falk MC, Shadbolt B, Kent AL. Antenatal and postnatal risk factors for neonatal hypertension and infant follow-up. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany). 2007 Dec:22(12):2081-7 [PubMed PMID: 17874136]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDionne JM, Abitbol CL, Flynn JT. Hypertension in infancy: diagnosis, management and outcome. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany). 2012 Jan:27(1):17-32. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1755-z. Epub 2011 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 21258818]

Flynn JT. Hypertension in the neonatal period. Current opinion in pediatrics. 2012 Apr:24(2):197-204. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32834f8329. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22426156]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencede Swiet M, Dillon MJ, Littler W, O'Brien E, Padfield PL, Petrie JC. Measurement of blood pressure in children. Recommendations of a working party of the British Hypertension Society. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 1989 Aug 19:299(6697):497 [PubMed PMID: 2507035]

Nascimento MC, Xavier CC, Goulart EM. Arterial blood pressure of term newborns during the first week of life. Brazilian journal of medical and biological research = Revista brasileira de pesquisas medicas e biologicas. 2002 Aug:35(8):905-11 [PubMed PMID: 12185382]

Blowey DL, Duda PJ, Stokes P, Hall M. Incidence and treatment of hypertension in the neonatal intensive care unit. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension : JASH. 2011 Nov-Dec:5(6):478-83. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2011.08.001. Epub 2011 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 21925997]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSharma D, Farahbakhsh N, Shastri S, Sharma P. Neonatal hypertension. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2017 Mar:30(5):540-550. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1177816. Epub 2016 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 27072362]

Sahu R, Pannu H, Yu R, Shete S, Bricker JT, Gupta-Malhotra M. Systemic hypertension requiring treatment in the neonatal intensive care unit. The Journal of pediatrics. 2013 Jul:163(1):84-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.12.074. Epub 2013 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 23394775]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAlagappan A, Malloy MH. Systemic hypertension in very low-birth weight infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia: incidence and risk factors. American journal of perinatology. 1998 Jan:15(1):3-8 [PubMed PMID: 9475679]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSharma D, Pandita A, Shastri S. Neonatal hypertension: an underdiagnosed condition, a review article. Current hypertension reviews. 2014:10(4):205-12 [PubMed PMID: 25694190]

Kilian K. Hypertension in neonates causes and treatments. The Journal of perinatal & neonatal nursing. 2003 Jan-Mar:17(1):65-74; quiz 75-6 [PubMed PMID: 12661740]

Sehgal A, Malikiwi A, Paul E, Tan K, Menahem S. Systemic arterial stiffness in infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia: potential cause of systemic hypertension. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2016 Jul:36(7):564-9. doi: 10.1038/jp.2016.10. Epub 2016 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 26914016]

Skalina ME, Kliegman RM, Fanaroff AA. Epidemiology and management of severe symptomatic neonatal hypertension. American journal of perinatology. 1986 Jul:3(3):235-9 [PubMed PMID: 3718646]

. Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, et al; SUBCOMMITTEE ON SCREENING AND MANAGEMENT OF HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE IN CHILDREN. Clinical Practice Guideline for Screening and Management of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017; 140(3):e20171904. Pediatrics. 2017 Dec:140(6):. pii: e20173035. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3035. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29192011]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStanley JC, Zelenock GB, Messina LM, Wakefield TW. Pediatric renovascular hypertension: a thirty-year experience of operative treatment. Journal of vascular surgery. 1995 Feb:21(2):212-26; discussion 226-7 [PubMed PMID: 7853595]

Anderson AH, Warady BA, Daily DK, Johnson JA, Thomas MK. Systemic hypertension in infants with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia: associated clinical factors. American journal of perinatology. 1993 May:10(3):190-3 [PubMed PMID: 8517893]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence