Introduction

The liver is one of the most common sites for cancer metastasis, accounting for nearly 25% of all cases.[1] A variety of primary tumors may be the source of metastasis; however, colorectal adenocarcinomas are the most prominent topic of research in the literature, as they are the most common. The dual blood supply of the liver not only makes it uniquely susceptible to metastasis from gastrointestinal cancers but also accessible to interventional therapies. Treatment strategies are rapidly evolving worldwide, with a movement towards an interprofessional approach for better outcomes.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Metastatic hepatic tumors are more prominent than primary hepatocellular or biliary tumors, although the majority of metastatic tumors are adenocarcinomas. Squamous cell carcinoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, and other far less common subtypes such as lymphoma, sarcoma, and melanoma also exist. By in large, the vast majority of the literature centers on the management of colorectal adenocarcinoma, which is reportedly the third most common primary malignancy worldwide. Nearly 70% to 80% of cases with metastatic disease remain confined to the liver.[2][3]

Epidemiology

Nearly 20% to 25% of patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer will develop liver metastases, with 15% to 25% of these cases presenting with synchronous disease.[4][5] The most common metastases originated from colorectal primaries, followed by pancreatic and breast. In females less than 50 years of age, metastatic hepatic disease originated more frequently from the breast. Metastatic liver disease in those older than 70 years old was from a gastrointestinal source; 92% of metastatic hepatic lesions were carcinomas. Of these carcinoma lesions, 75% of them were adenocarcinomas.[3] Overall, histologically confirmed hepatic metastases were more common in males than females, and most patients were older than 50 years of age.

Pathophysiology

The liver is supplied by both the hepatic artery and the portal vein. The portal vein collects venous drainage from the pancreas, spleen, and almost all of the gastrointestinal tract. Typically, this allows for the liver to process newly digested and absorbed nutrients in first-pass metabolism. In the setting of malignancy, it also means the liver can receive metastasis from a wide variety of abdominal and extra-abdominal malignancies. As a result of liver metastasis, patients may have a variety of symptoms depending on disease burden and location. These include abdominal pain, ascites, jaundice, weight loss, and fatigue.

While the hepatocytes are supplied by the portal vein, the cholangiocytes of the biliary system are supplied by the hepatic artery. It is thought that metastatic liver tumors derive their blood supply from the hepatic artery. This presents a unique opportunity for liver-directed therapies that target tumor cells while sparing hepatocytes. In addition, the liver has the ability to hypertrophy to compensate for the loss of function. As long as the vascular supply to the liver and biliary drainage remain intact, up to 80% of the liver can be removed. The remanent will hypertrophy to restore full hepatic function within weeks. This can allow for more aggressive hepatic resections in the case of multiple metastases.

Histopathology

In patients with a liver biopsy, it is essential to understand the morphology and anatomic site of origin of the tumor cells to dictate targeted chemotherapy and to understand the disease prognosis. A diagnosis can be determined upon morphology alone; however, a series of additional biomarkers such as cytokeratins, S100, and leukocyte-common antigen (LCA) may assist in further categorizing the specific organ of origin.[6] CK19 has been associated with adenocarcinoma, thus differentiating it from hepatocellular carcinoma. Other tumor markers such as C-kit, CD34, and vimentin have correlations with GISTs.

Malignant melanomas have demonstrated the highest sensitivity with S100+, although HMB45, MelanA-positive, and MART-1 are other biomarkers. Neuroendocrine carcinomas require testing for synaptophysin, chromogranin, and CD56. The vast majority of tumors will be carcinomas, specifically adenocarcinomas that become further delineated via their differentiation, mitoses, immunohistochemical studies, and overall appearance. CK7 and CK20 have been used as initial differentiating markers for tumor origin, as well as estrogen receptors in the case of metastatic lobular breast carcinoma.

History and Physical

An interprofessional approach with medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, interventional and diagnostic radiologists, and surgical oncologists to address the patient’s condition is essential.[7][8] As previously mentioned, there is no robust data on an asymptomatic versus symptomatic presentation from a patient’s history and physical, as there are a number of symptoms including distention, early satiety, vague abdominal complaints, changes in bowel habits, hematochezia, weight loss, encephalopathy, jaundice, ascites, and metabolic disturbances should all raise suspicion for metastatic disease, but there are no pathognomonic findings for liver metastasis.

Physical examination findings associated with classic findings of hepatic disease (caput medusa, hepatosplenomegaly, ascites) should also prompt a thorough evaluation. It is essential to perform a rectal exam with a subsequent colonoscopy to check for masses and blood in the stool. Patients with a strong family history of colon cancer or who are past due for their colonoscopy should receive screening. As hepatic disease may arise from elsewhere, a thorough physical exam auscultating for adequate breath sounds and palpation of lymphadenopathy are important in decision-making for care.

Evaluation

High-quality imaging is essential in the evaluation of suspected liver metastasis. It can confirm the diagnosis as well as aid in identifying the primary disease. The most common imaging modalities include triple-phase CT and MRI scans. The triple-phase CT scan consists of a non-contrast phase, arterial phase, and venous phase. Liver metastasis and primary liver tumors tend to have the strongest attenuation in the arterial phase and tend to be hypo attenuating in non-contrast studies. CT is particularly advantageous as it can aid in tumor localization which can be used during the planning of liver-directed therapies. CT imaging evaluates metastatic tumor size, morphology, degree of liver disease, and the predicted future liver remnant. It is critical to determine the potential resectability of liver tumors, as lesions near major vascular structures may be inoperable. MRI is another modality that can be utilized if there is difficulty characterizing a liver lesion. Liver metastasis on T1 weighted imaging appears hypo-intense and hyperintense on T2 imaging. Gadolinium contrast-enhanced T1 weighted images can show total or rim enhancement depending on the size.

Other contrast agents such as gadoxetate disodium (Eovist) and gadobenate dimeglumine (Multihance) have been designed to enhance the sensitivity of MRI. The challenge is that there exist several benign conditions that can mimic liver metastasis on imaging. Fluorodeoxyglucose-18 (FDG) PET/CT can aid in the detection of hepatic metastasis and may assist in identifying primary and extrahepatic metastasis. However, it has poorer anatomic resolution than CT and is insensitive in detecting lesions smaller than 1cm in size. Despite this, there are instances where PET/CT has been useful specifically in detecting metastatic neuroendocrine carcinomas, namely gallium-68 DOTATATE PET imaging. Ultrasonography has poorer sensitivity and is not routinely used in diagnostic workups. The workup should also include basic liver function tests, complete blood count, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), and colonoscopy.[9][10]

Treatment / Management

While surgical resection remains the standard of care, several techniques are available for treating liver metastasis in medically or surgically inoperable patients. Most of the data on outcomes in this setting is related to colorectal malignancies, but data from neuroendocrine and primary liver disease has also provided valuable insight. Less invasive techniques such as stereotactic body radiotherapy have been utilized, and embolization techniques with either chemotherapy or radioactive isotopes with reasonable outcomes and acceptable toxicity levels.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for hepatic lesions remains broad. Imaging and history will help delineate and focus on more common etiologies; however, some differential disease processes may be primary hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, adenoma, hemangioma, hematoma, focal nodular hyperplasia, abscess, or secondary masses from metastatic disease (carcinoma, lymphoma, sarcoma).[11]

Surgical Oncology

Surgical resection of hepatic metastases with adjuvant chemotherapy is associated with improved survival outcomes and reduced morbidity and mortality. Because colorectal adenocarcinoma is the most common form of hepatic metastasis, the vast majority of the literature centers on this disease process. Other specific clinical scenarios receive treatment on a personalized basis.

Surgical resection remains the gold standard for anatomically resectable colorectal hepatic metastases. Clinical guidelines have indicated that the future liver remnant is at least 20% of its original volume in a healthy liver, 30% with mild to moderate hepatic dysfunction, and 40% with hepatic cirrhosis.[8] Strategies to improve the chances of resection include neoadjuvant chemotherapy, portal vein embolization to increase the future liver remnant or a two-stage resection versus a combined one-stage resection of the primary tumor and hepatic lesions.

The goal of surgery should be the removal of all gross disease with negative microscopic margins of 1 mm. Studies have shown that the degree of the resection margin has not demonstrated a significant difference in survival, as long as tumor margins are negative.[12] An open or laparoscopic approach to surgery is an option for hepatic resection. A recent meta-analysis supports the use of laparoscopy for similar cancer-specific long-term outcomes compared to open procedures with the added benefit of fewer short-term complications.[13] Simultaneous resection for synchronous colorectal carcinoma and hepatic metastases is acceptable when there is favorable anatomy for partial hepatic resection. One-stage versus a two-stage surgical resection of the primary colorectal tumor and hepatic metastasis have shown comparable efficacy. A one-stage approach reduces the overall length of hospital stay. Other aspects, such as morbidity and mortality, have varied among studies.[14] Delaying liver resection has shown not to decrease survival in patients needing resection when neoadjuvant chemotherapy is a consideration.[15]

It is important to distinguish between asymptomatic and symptomatic primary tumors, as patients who are anemic, obstructed, or actively ill from the primary tumor should have that resection first. Extra-hepatic disease and metastatic liver disease have shown significantly lower five-year survival rates (28% versus 55%). Predictors of poor cancer-specific survival outcomes are extra-hepatic disease other than lung, extra-hepatic disease in addition to colorectal metastatic recurrence, carcinoembryonic antigen level (CEA) greater than 10 ng/mL, right-sided colon cancer, and more than six colorectal liver metastatic lesions.[16]

If utilizing neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, in general, 4 to 6 months of therapy is delivered before surgery. Fluorouracil-based chemotherapy serves as the base treatment, as its administration is in addition to other agents in combinations such as FOLFOX and FOLFIRI.[17] It works to decrease both the number and size of metastases pre-operatively, and it aims to reduce recurrence postoperatively. Although the standard of care is for surgery and perioperative chemotherapy, some studies have questioned the benefit of chemotherapy and surgery versus surgery alone. Some studies have shown no significant improvement in median overall survival; however, other groups have demonstrated an observed survival benefit.[10] Specifically, one observational study demonstrated preoperative chemotherapy compared to patients who underwent resection followed by chemotherapy had a greater percentage of patients with three-year disease-free survival (31.7% to 20.4%, respectively).[18]

Radiation Oncology

Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy (SBRT)

Ablative doses of highly conformal short-course radiotherapy have been explored extensively in several settings, especially for use in the metastatic setting. Recent clinical trials have shown a survival benefit in patients with oligo metastatic (<5 metastasis) treated with radiotherapy (SABR COMET). The data for the use of SBRT in the setting of liver metastasis is encouraging. It offers a far less invasive approach to treatment with excellent local control and acceptable toxicity compared to hepatic resection or even other less invasive measures such as radiofrequency ablation and Trans arterial chemo/radioembolization (TACE/TARE). Local control rates at one year were 87% and 68% at three years, and overall survival of 84% at one year and 44% at three years.[19] Grade 3+ toxicity is observed in less than 5% of patients. Dose and fractionation schemes vary, but evidence suggests superior local control with biological equivalence doses that exceed 100Gy.[20] At this time, prospective comparisons of SBRT with other liver-directed therapies are lacking, but SBRT remains a feasible, efficacious, and non-invasive treatment modality for patients with liver metastasis.

Linac-based SBRT is one of the most common means of performing this technique, although proton therapy and dedicated SBRT systems such as Cyberknife (Accuray) are also available. The simulation must take into consideration respiratory motion. There are several tumor motion management techniques. A 4D CT planning scan allows for the tumor to be tracked as a function of the phase in the respiratory cycle to ensure that the planning target volume encompasses the tumor throughout the respiration. Alternatively, abdominal compression devices can be used in some patients to limit tumor motion. Respiratory gating or breath hold may also be used to limit the size of the target volume by only allowing radiation delivery during specific phases of the respiratory cycle. Fiducial markers placed into the tumor before treatment can also aid tumor tracking and targeting. Fusing other contrast-enhanced imaging studies such as diagnostic MRI or CT to the CT simulation is necessary for target delineation. Multiple static coplanar/non-coplanar fields or volumetric arc therapy (VMAT) can be utilized as a part of planning with the goal of creating a highly conformal plan with rapid dose falloff outside the planning target volume. Image-guided radiation therapy (IGRT) is essential for accurate targeting and can include kV or MV Cone Beam CT, kV fluoroscopy, or ultrasound. Dose and fractionation schedules vary but are typically 30 to 60Gy in 1 to 6 fractions, with the goal biologic equivalent dose (BED) should exceed 100Gy.[20][21]

Dose constraints for normal structures such as normal liver parenchyma, kidneys, spinal cord, stomach, heart, and small bowel must be evaluated. Task Group-101, which was published by the American Academy of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM), and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines provide dose constraints for SBRT for 1, 3, and 5 fraction courses.[22][23] What is critical is the amount of normal liver receiving less than 15Gy should be greater than 700cc in a 3-fraction course of SBRT and less than 21Gy for a 5-fraction course which minimizes the risk of radiation-induced liver disease (RILD). Bowel dose can also be challenging to meet dose constraints depending on the location of the metastasis.

Conformal Radiotherapy

Lower doses and a more protracted radiation regimen may be necessary for situations where the liver tumors are too large to be treated with SBRT. These tumors are typically treated with 3D conformal radiation with doses ranging from 48-73Gy in 1.5-1.65Gy/fraction twice daily with a response rate of 60%.[21]

Whole Liver Radiation

In contrast to the highly conformal and ablative doses delivered by SBRT, whole liver radiation is typically delivered as a low dose in patients with painful liver metastasis with a significant disease burden. This treatment modality has the advantage of being relatively easier to plan and execute, but it is strictly a palliative measure. There has been no documented survival benefit or synergistic effect when combined with chemotherapy. Patients selected for this type of treatment have limited life expectancy, significant disease burden, and/or have exhausted other treatment options. The treatment schedule is typically short, ranging from 1 to 3 fractions with a dose of 8 to 21Gy in 1 to 3 fractions, with 80% of patients reporting pain relief duration of 13 weeks.[21] The threshold with RILD is typically around 30Gy with conventionally fractionated radiotherapy to the whole liver. These patients should be premedicated with antiemetics and steroids prior to treatment.

Trans-arterial Radioembolization

Trans-Arterial Radioembolization (TARE) takes advantage of the liver’s dual blood supply using Yttrium-90 (Y-90) glass microspheres. An internal approach coupled with a Beta emitter such as Y-90 allows, which has maximal penetration of approximately 1cm and a short half-life (64.2 hours), is ideal because it minimizes dose to uninvolved liver parenchyma. There are two commercially available Y-90 systems; TheraSpheres and Sir-Shere. Eligible patients are those that are not candidates for resection, ECOG ≤ 2, and life expectancy exceeding three months. Contraindications to TARE include total bilirubin exceeding 2mg/dL, Childs Pugh C, ECOG 3+, >20% lung shunting, or a lung dose ≥ 30Gy in a single application.[24] The SIRFLOX study, which examined the use of Y-90 radio-embolization in chemotherapy naïve metastatic colorectal patients with liver metastasis, failed to improve progression-free survival compared to chemotherapy alone, but it significantly delayed progression in the liver.[25] A recent open-label randomized prospective trial for patients with colorectal liver metastasis with progression on first-line therapy was randomized to receive second-line chemotherapy along +/- TARE. The TARE group has improved progression-free and hepatic progression-free survival.[26]

After patient pre-selection, treatment planning will commence. This will include a diagnostic angiography in which micro aggregates of Tc-99m labeled albumin are then injected, which have a similar dispersion pattern to Y-90 microspheres and is monitored using a SPECT scan. During the planning phase, pulmonary shunting may be identified as vascular abnormalities. These issues may be corrected by embolization, but if they cannot, these would disqualify the patient from treatment. After treatment planning, dose calculations must be performed to determine the level of activity required. The calculations are dependent on the type of spheres being used. If using TheraSpheres, then the activity required is A = 120 (Gy) × M/[(1 - S) × 50], where M is the mass of the whole liver and S is the lung-liver shunt.[24] The goal dose is 120Gy, and the activity needed to attain this is dictated by the equation. For Sir-Sphere, four different methods can be used: Empirical Method, Body Surface Area Method, Partition Model, and Voxel dosimetry. These models differ in the amount of healthy liver tissue irradiated.[24] Treatment usually commences four weeks post-planning. Complications include radiation-induced liver disease (RILD), post-radio embolization syndrome (PRS), neutropenia, liver abscess, and gastric perforation.[21][24]

Trans-arterial Chemoembolization (TACE)

TACE has been investigated as well as a potential treatment for patients with chemorefractory metastatic colorectal cancer. It takes advantage of the same vascular properties of the liver as TARE. Most of the data is retrospective, showing disease stabilization in 40 to 60% of patients. A small prospective Phase III randomized trial comparing systemic FOLFIRI alone to FOLIRI with intra-arterial irinotecan eluting beads demonstrated a higher objective response rate and improved median survival.[27]

Hyperthermic Ablation

The use of high temperatures (>60C) to ablate liver tumors can be accomplished by two techniques: Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or Microwave ablation (MWA). Both techniques rely on heating tumor cells, causing denaturation of proteins, destruction of the cell membrane, and coagulative necrosis.

Radiofrequency ablation utilizes uninsulated electrodes through which alternating electrical current is passed through the patient at a frequency of 375 to 500 kHz. This allows for the development of ionic friction, thus generating heat. RFA is ineffective near major heat sinks such as large vessels, and there is a risk of thermal injury to the bile ducts, diaphragm, and bowel. In addition, there can be interference with cardiac pacemakers. Local recurrence rates range from 10 to 31% depending, but this is dependent on the size and location of the metastasis.[28] RFA is a well-tolerated technique with few complications. Post-ablation syndrome occurs in about 30-40% of patients and consists of fever, chills, nausea, and vomiting but tends to be self-limiting.[29]

Microwave Ablation heats tumors through dielectric hysteresis of water molecules with frequencies ranging from 0.915 to 2.45GHz.[30] It is unclear at this time which method, but local recurrence rates range from 5 to 13%.[28] Theoretical advantages include less heat sink effect due to the method of heating and higher intratumoral temperatures. The procedure can be performed using open, laparoscopic, or percutaneously. Image guidance with CT, MRI, or ultrasound is used to localize the tumor. Outcomes are dependent on operator experience as well as the size of the tumor. This modality is limited to less than five tumors measuring less than 3cm. Local control rates drop quickly when tumors exceed 3 cm (85% vs. 39%).[31] The COLLISION Trial is an ongoing prospective non-inferiority trial comparing thermal ablation to surgical resection in patients with colorectal metastasis ≤ 3 cm with an estimated study completion date of December 2022.[32]

Medical Oncology

Systemic chemotherapy has demonstrated objective response rates; however, a complete pathological response is rare. There is no consensus in the literature regarding the optimal duration of chemotherapy, but a minimum of three to six months on a select regimen is advocated before changing agents. When offering non-first-line chemotherapy agents that include biologic medications, the morbidity of side effects must be weighed against the patient's clinical status. Careful monitoring must be employed, as there have been mixed data on their success rates in treating hepatic metastases.[33]

Prognosis

The majority of the literature has centered on colorectal metastases. The prognosis for patients without treatment for synchronous disease is significant. There is a 5% five-year survival rate with no treatment. The five-year survival after curative resection of hepatic lesions may be up to 58%, in contrast to a median of 6 months of survival with no treatment.[34][35]

Neuroendocrine liver metastases that can undergo partial hepatectomy have slightly higher survival rates than colorectal carcinoma, as survival rates are 61% at five years.[36]

Complications

Patients may develop postoperative hepatectomy complications such as abscess formation, biliary leaks, recurrent disease, bleeding, sepsis, damage to surrounding structures, and the need for further operative intervention. Other complications may relate to preoperative systemic chemotherapy and include steatohepatitis, sinusoidal obstruction, leukopenia, system infections, fever, fatigue, weight loss, poor wound healing, and other potential side effects. Radiation-induced liver disease (RILD) can occur if the dose to the whole liver exceeds known toxicity thresholds that depend on volume, dose, and fractionation. Other complications of external beam radiotherapy include bowel perforation and spinal cord injury. Post-embolization syndrome is a common complication of TARE, which consists of fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Diagnosing metastatic disease to the liver is difficult, as this constitutes stage IV disease from another primary site. The prognosis is poor without treatment. It requires an interprofessional approach with medical, radiological, and surgical oncology to coordinate a patient-centered treatment plan with the hope of using chemotherapy and surgical resection to increase overall survival. There is a consensus on chemotherapy agents; however, surgical planning varies based on patient presentation. Although there is no way to prevent metastases, it is essential to see a primary provider annually for screening with physical exams, colonoscopies, and blood work.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Interprofessional team communication and proper care coordination are paramount when caring for sick patients with liver metastases. A hepatobiliary and oncologic team should evaluate pre and postoperative imaging modalities, chemotherapy regimens, and surgical interventions tailored to the patient. Further studies into the histopathological diagnosis of the disease may help direct more targeted preoperative chemotherapy regimens for an easier and more functional hepatic resection. Oncology specialty nurses monitor patients, provide education, and report patient status to the team. Board-certified oncology pharmacists assist in agent selection, dosing, and checking for drug-drug interactions. With an interprofessional approach to care, patients can attain better outcomes in metastatic hepatic disease. [Level 5] Patients with significant disease should receive treatment within a larger hospital system with higher patient volumes and open access to patient information, so all interprofessional team members operate from the same up-to-date data for better care.

Media

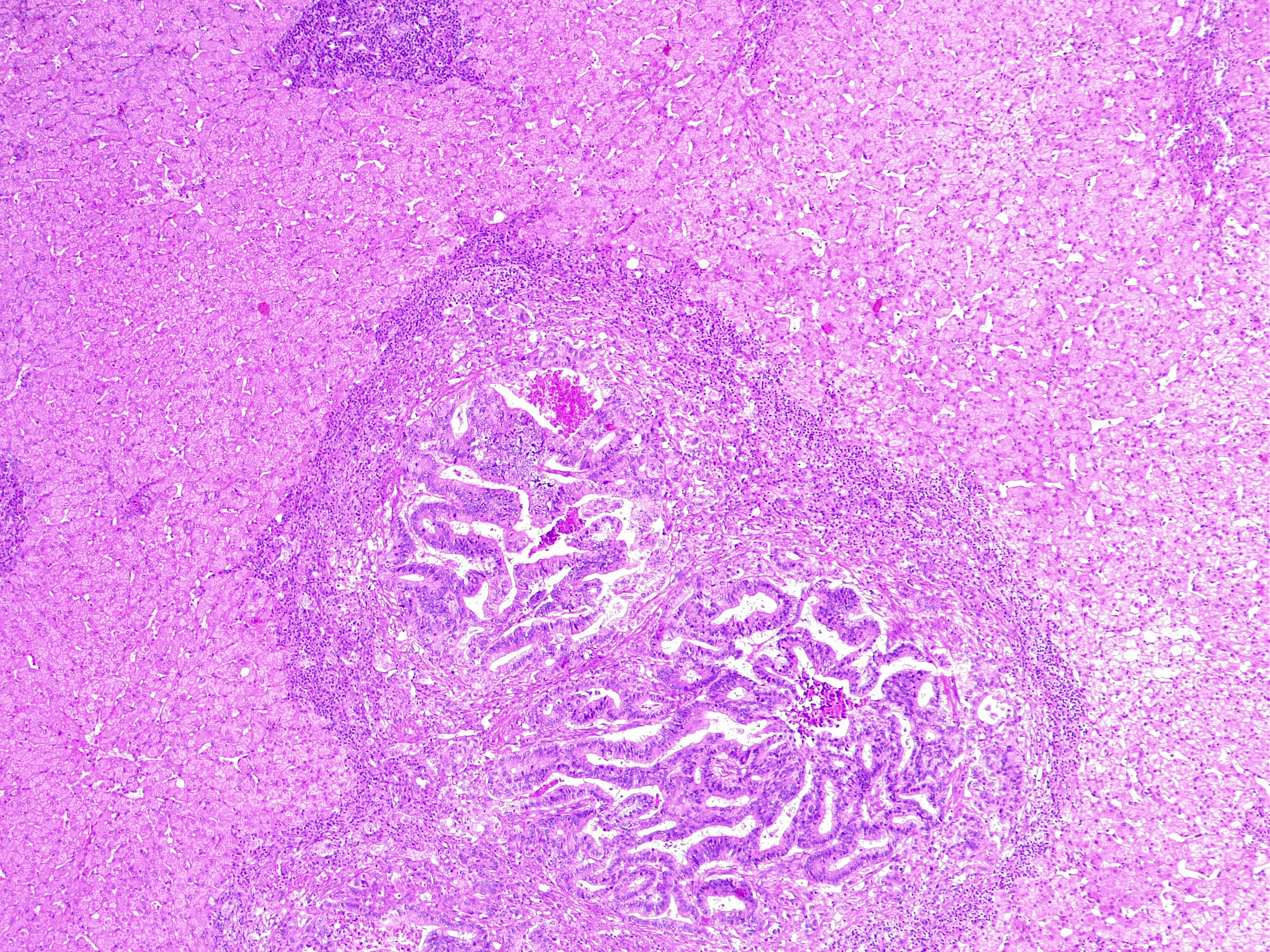

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Liver Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer. This microscopic image shows a neoplastic nodule composed of glandular structures surrounded by fibrous and inflammatory tissue. This case is an example of metastatic colorectal cancer, adenocarcinoma type. This finding classifies as adenocarcinoma TNM stage pM1.

Contributed by Fabiola Farci, MD

References

Abbruzzese JL, Abbruzzese MC, Lenzi R, Hess KR, Raber MN. Analysis of a diagnostic strategy for patients with suspected tumors of unknown origin. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1995 Aug:13(8):2094-103 [PubMed PMID: 7636553]

Weiss L. Comments on hematogenous metastatic patterns in humans as revealed by autopsy. Clinical & experimental metastasis. 1992 May:10(3):191-9 [PubMed PMID: 1582089]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencede Ridder J, de Wilt JH, Simmer F, Overbeek L, Lemmens V, Nagtegaal I. Incidence and origin of histologically confirmed liver metastases: an explorative case-study of 23,154 patients. Oncotarget. 2016 Aug 23:7(34):55368-55376. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10552. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27421135]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHugen N, van de Velde CJH, de Wilt JHW, Nagtegaal ID. Metastatic pattern in colorectal cancer is strongly influenced by histological subtype. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2014 Mar:25(3):651-657. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt591. Epub 2014 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 24504447]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDisibio G, French SW. Metastatic patterns of cancers: results from a large autopsy study. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2008 Jun:132(6):931-9 [PubMed PMID: 18517275]

Centeno BA. Pathology of liver metastases. Cancer control : journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center. 2006 Jan:13(1):13-26 [PubMed PMID: 16508622]

Gallinger S, Biagi JJ, Fletcher GG, Nhan C, Ruo L, McLeod RS. Liver resection for colorectal cancer metastases. Current oncology (Toronto, Ont.). 2013 Jun:20(3):e255-65. doi: 10.3747/co.20.1341. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23737695]

Maher B, Ryan E, Little M, Boardman P, Stedman B. The management of colorectal liver metastases. Clinical radiology. 2017 Aug:72(8):617-625. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2017.05.016. Epub 2017 Jun 24 [PubMed PMID: 28651746]

Van Cutsem E, Nordlinger B, Cervantes A, ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Advanced colorectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for treatment. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2010 May:21 Suppl 5():v93-7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq222. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20555112]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMitchell D, Puckett Y, Nguyen QN. Literature Review of Current Management of Colorectal Liver Metastasis. Cureus. 2019 Jan 23:11(1):e3940. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3940. Epub 2019 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 30937238]

Manfredi S, Lepage C, Hatem C, Coatmeur O, Faivre J, Bouvier AM. Epidemiology and management of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Annals of surgery. 2006 Aug:244(2):254-9 [PubMed PMID: 16858188]

Adam R, de Gramont A, Figueras J, Kokudo N, Kunstlinger F, Loyer E, Poston G, Rougier P, Rubbia-Brandt L, Sobrero A, Teh C, Tejpar S, Van Cutsem E, Vauthey JN, Påhlman L, of the EGOSLIM (Expert Group on OncoSurgery management of LIver Metastases) group. Managing synchronous liver metastases from colorectal cancer: a multidisciplinary international consensus. Cancer treatment reviews. 2015 Nov:41(9):729-41. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.06.006. Epub 2015 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 26417845]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCiria R, Ocaña S, Gomez-Luque I, Cipriani F, Halls M, Fretland ÅA, Okuda Y, Aroori S, Briceño J, Aldrighetti L, Edwin B, Hilal MA. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing the short- and long-term outcomes for laparoscopic and open liver resections for liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Surgical endoscopy. 2020 Jan:34(1):349-360. doi: 10.1007/s00464-019-06774-2. Epub 2019 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 30989374]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLykoudis PM, O'Reilly D, Nastos K, Fusai G. Systematic review of surgical management of synchronous colorectal liver metastases. The British journal of surgery. 2014 May:101(6):605-12. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9449. Epub 2014 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 24652674]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLambert LA, Colacchio TA, Barth RJ. Interval hepatic resection of colorectal metastases improves patient selection*. Current surgery. 2000 Sep 1:57(5):504 [PubMed PMID: 11064085]

Adam R, de Haas RJ, Wicherts DA, Vibert E, Salloum C, Azoulay D, Castaing D. Concomitant extrahepatic disease in patients with colorectal liver metastases: when is there a place for surgery? Annals of surgery. 2011 Feb:253(2):349-59. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318207bf2c. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21178761]

Khoo E, O'Neill S, Brown E, Wigmore SJ, Harrison EM. Systematic review of systemic adjuvant, neoadjuvant and perioperative chemotherapy for resectable colorectal-liver metastases. HPB : the official journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association. 2016 Jun:18(6):485-93. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2016.03.001. Epub 2016 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 27317952]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKim CW, Lee JL, Yoon YS, Park IJ, Lim SB, Yu CS, Kim TW, Kim JC. Resection after preoperative chemotherapy versus synchronous liver resection of colorectal cancer liver metastases: A propensity score matching analysis. Medicine. 2017 Feb:96(7):e6174. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006174. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28207557]

Méndez Romero A, Schillemans W, van Os R, Koppe F, Haasbeek CJ, Hendriksen EM, Muller K, Ceha HM, Braam PM, Reerink O, Intven MPM, Joye I, Jansen EPM, Westerveld H, Koedijk MS, Heijmen BJM, Buijsen J. The Dutch-Belgian Registry of Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Liver Metastases: Clinical Outcomes of 515 Patients and 668 Metastases. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2021 Apr 1:109(5):1377-1386. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.11.045. Epub 2021 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 33451857]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKok END, Jansen EPM, Heeres BC, Kok NFM, Janssen T, van Werkhoven E, Sanders FRK, Ruers TJM, Nowee ME, Kuhlmann KFD. High versus low dose Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for hepatic metastases. Clinical and translational radiation oncology. 2020 Jan:20():45-50. doi: 10.1016/j.ctro.2019.11.004. Epub 2019 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 31886419]

Høyer M, Swaminath A, Bydder S, Lock M, Méndez Romero A, Kavanagh B, Goodman KA, Okunieff P, Dawson LA. Radiotherapy for liver metastases: a review of evidence. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2012 Mar 1:82(3):1047-57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.07.020. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22284028]

Benedict SH, Yenice KM, Followill D, Galvin JM, Hinson W, Kavanagh B, Keall P, Lovelock M, Meeks S, Papiez L, Purdie T, Sadagopan R, Schell MC, Salter B, Schlesinger DJ, Shiu AS, Solberg T, Song DY, Stieber V, Timmerman R, Tomé WA, Verellen D, Wang L, Yin FF. Stereotactic body radiation therapy: the report of AAPM Task Group 101. Medical physics. 2010 Aug:37(8):4078-101 [PubMed PMID: 20879569]

Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL, Akerley W, Bauman JR, Bharat A, Bruno DS, Chang JY, Chirieac LR, D'Amico TA, Dilling TJ, Dowell J, Gettinger S, Gubens MA, Hegde A, Hennon M, Lackner RP, Lanuti M, Leal TA, Lin J, Loo BW Jr, Lovly CM, Martins RG, Massarelli E, Morgensztern D, Ng T, Otterson GA, Patel SP, Riely GJ, Schild SE, Shapiro TA, Singh AP, Stevenson J, Tam A, Yanagawa J, Yang SC, Gregory KM, Hughes M. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 2.2021. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2021 Mar 2:19(3):254-266. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0013. Epub 2021 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 33668021]

Sacco R, Mismas V, Marceglia S, Romano A, Giacomelli L, Bertini M, Federici G, Metrangolo S, Parisi G, Tumino E, Bresci G, Corti A, Tredici M, Piccinno M, Giorgi L, Bartolozzi C, Bargellini I. Transarterial radioembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: An update and perspectives. World journal of gastroenterology. 2015 Jun 7:21(21):6518-25. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i21.6518. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26074690]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencevan Hazel GA, Heinemann V, Sharma NK, Findlay MP, Ricke J, Peeters M, Perez D, Robinson BA, Strickland AH, Ferguson T, Rodríguez J, Kröning H, Wolf I, Ganju V, Walpole E, Boucher E, Tichler T, Shacham-Shmueli E, Powell A, Eliadis P, Isaacs R, Price D, Moeslein F, Taieb J, Bower G, Gebski V, Van Buskirk M, Cade DN, Thurston K, Gibbs P. SIRFLOX: Randomized Phase III Trial Comparing First-Line mFOLFOX6 (Plus or Minus Bevacizumab) Versus mFOLFOX6 (Plus or Minus Bevacizumab) Plus Selective Internal Radiation Therapy in Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016 May 20:34(15):1723-31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.1181. Epub 2016 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 26903575]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMulcahy MF, Mahvash A, Pracht M, Montazeri AH, Bandula S, Martin RCG 2nd, Herrmann K, Brown E, Zuckerman D, Wilson G, Kim TY, Weaver A, Ross P, Harris WP, Graham J, Mills J, Yubero Esteban A, Johnson MS, Sofocleous CT, Padia SA, Lewandowski RJ, Garin E, Sinclair P, Salem R, EPOCH Investigators. Radioembolization With Chemotherapy for Colorectal Liver Metastases: A Randomized, Open-Label, International, Multicenter, Phase III Trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2021 Dec 10:39(35):3897-3907. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01839. Epub 2021 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 34541864]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFiorentini G, Aliberti C, Tilli M, Mulazzani L, Graziano F, Giordani P, Mambrini A, Montagnani F, Alessandroni P, Catalano V, Coschiera P. Intra-arterial infusion of irinotecan-loaded drug-eluting beads (DEBIRI) versus intravenous therapy (FOLFIRI) for hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: final results of a phase III study. Anticancer research. 2012 Apr:32(4):1387-95 [PubMed PMID: 22493375]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePathak S, Jones R, Tang JM, Parmar C, Fenwick S, Malik H, Poston G. Ablative therapies for colorectal liver metastases: a systematic review. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2011 Sep:13(9):e252-65. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02695.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21689362]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWah TM, Arellano RS, Gervais DA, Saltalamacchia CA, Martino J, Halpern EF, Maher M, Mueller PR. Image-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation and incidence of post-radiofrequency ablation syndrome: prospective survey. Radiology. 2005 Dec:237(3):1097-102 [PubMed PMID: 16304121]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBirrer DL, Tschuor C, Reiner C, Fritsch R, Pfammatter T, Garcia Schüler H, Pavic M, De Oliveira M, Petrowsky H, Dutkowski P, Oberkofler C, Clavien PA. Multimodal treatment strategies for colorectal liver metastases. Swiss medical weekly. 2021 Feb 15:151():w20390. doi: 10.4414/smw.2021.20390. Epub 2021 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 33631027]

Wang CZ, Yan GX, Xin H, Liu ZY. Oncological outcomes and predictors of radiofrequency ablation of colorectal cancer liver metastases. World journal of gastrointestinal oncology. 2020 Sep 15:12(9):1044-1055. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v12.i9.1044. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33005297]

Puijk RS, Ruarus AH, Vroomen LGPH, van Tilborg AAJM, Scheffer HJ, Nielsen K, de Jong MC, de Vries JJJ, Zonderhuis BM, Eker HH, Kazemier G, Verheul H, van der Meijs BB, van Dam L, Sorgedrager N, Coupé VMH, van den Tol PMP, Meijerink MR, COLLISION Trial Group. Colorectal liver metastases: surgery versus thermal ablation (COLLISION) - a phase III single-blind prospective randomized controlled trial. BMC cancer. 2018 Aug 15:18(1):821. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4716-8. Epub 2018 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 30111304]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePower DG, Kemeny NE. Chemotherapy for the conversion of unresectable colorectal cancer liver metastases to resection. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2011 Sep:79(3):251-64. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.08.001. Epub 2010 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 20970353]

Ito H, Are C, Gonen M, D'Angelica M, Dematteo RP, Kemeny NE, Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Jarnagin WR. Effect of postoperative morbidity on long-term survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer. Annals of surgery. 2008 Jun:247(6):994-1002. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31816c405f. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18520227]

Pawlik TM, Scoggins CR, Zorzi D, Abdalla EK, Andres A, Eng C, Curley SA, Loyer EM, Muratore A, Mentha G, Capussotti L, Vauthey JN. Effect of surgical margin status on survival and site of recurrence after hepatic resection for colorectal metastases. Annals of surgery. 2005 May:241(5):715-22, discussion 722-4 [PubMed PMID: 15849507]

Sarmiento JM, Heywood G, Rubin J, Ilstrup DM, Nagorney DM, Que FG. Surgical treatment of neuroendocrine metastases to the liver: a plea for resection to increase survival. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2003 Jul:197(1):29-37 [PubMed PMID: 12831921]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence