Introduction

Central sleep apnea (CSA) is characterized by transient diminution or cessation of the respiratory rhythm generator located within the pontomedullary region of the brain. In general, CSA represents an array of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) conditions due to the brief absence of ventilatory output during sleep. CSA manifests as a cyclical phenomenon/pattern during sleep; periods of apnea or hypopnea alternating with hyperpnea. Although there is a lack of effort during central events, it has been found that the upper airway narrows or nearly collapses during these events. Upper airway narrowing consistently occurs at the retropalatal level during induced hypocapnic central apnea (video 1) and induced central hypopnea.[1]

Though the prevalence of CSA is lower than OSA, both conditions often coexist, and patients can exhibit features of both states. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders – Third Edition (ICSD-3) [2] has divided CSA syndromes into several categories based on distinct clinical and polysomnographic features;

- Primary CSA

- CSA with Cheyne-Stokes Breathing (CSB)

- CSA due to a medical disorder without CSB

- CSA due to a periodic high-altitude breathing

- CSA due to a medication or substance

- Treatment-emergent CSA

Both hypoventilation and hyperventilation can result in central apneas, and each one acts through a distinct pathophysiological pathway. Thus, the degree of alveolar ventilation often serves as a basis for an alternate classification of CSA. Patients with heart failure are often hypocapnic during wakefulness and have an increased propensity to develop hyperventilation related CSA; however, hypoventilation related CSA commonly occur in neuromuscular diseases (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, brainstem stroke), overuse of medications with side effects of central nervous system depression (opioids), cervical spinal cord injury and structural abnormalities affecting pulmonary dynamics (kyphoscoliosis).[3][4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Patients with various medical conditions tend to develop central breathing instability during sleep, perpetuating CSA. Atrial fibrillation (AF), heart failure (HF) either with preserved or reduced ejection fraction (EF), ischemic stroke, spinal cord injury, renal failure, and chronic opioid use predispose patients to acquire central apnea via transient diminution of ventilatory output. CSA occurs predominantly in most cardiovascular conditions, and itself is an independent risk factor associated with poor outcomes. In rare instances, no apparent cause is identified and thus, is referred to as idiopathic or primary.[5]

Epidemiology

Bixler et al. demonstrated that the central apnea index was higher in older adults when compared to the middle age group (12.1% vs. 1.8%).[6] The prevalence of CSA tends to increase with age and is higher in the elderly population above 65 years of age. A cross-sectional study reported the prevalence of CSA in men aged 65 years and older as 2.7% by using a modified form of the ICSD-3 classification.[7]

It can be explained by relatively increased chemo responsiveness in the elderly population that prone them to develop central apnea, particularly during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep.[8] Compared with men, women are less susceptible and often require a larger magnitude of hypocapnia to develop central apnea.[9]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of CSA can be variable due to its temporal relation with different comorbidities. Depending on the underlying medical condition, hypoventilation or hyperventilation with resultant hypocapnia below an apneic threshold is an integral mechanism that reinforces the evolution of central apnea. Reduced ventilatory drive during NREM sleep can induce central apnea and hypopnea even in healthy individuals. The mechanism is complex, but studies have shown that central chemoreceptors and upper airway mechanics play important roles.[10][11] In addition, ventilatory control can contribute to the resultant central apnea in a susceptible patient population, particularly patients with neuromuscular disorders (such as spinal cord injury) or chest wall abnormalities (such as kyphoscoliosis).

The enhanced chemosensitivity to arterial carbon dioxide levels during sleep results in overall increased loop gain, leading to ventilatory instability and CSA, especially in patients with HF.[12] Opioids and other medications with CNS sedating properties can suppress the respiratory rhythm generator located within the brainstem. Thus, the development of CSA can be attributed either to reduced central ventilatory motor output or high loop gain. Regardless of the underlying condition or mechanism, once a cycle has started, it perpetuates the next one, resulting in repetitive episodes of hypoxia and irregular breathing, ultimately leading to upper airway narrowing.[1]

History and Physical

Patients with CSA present with stereotypical complaints related to disrupted sleep, which are akin to the other forms of sleep apnea. They typically complain of poor-quality sleep, nocturnal awakening, sleep fragmentation, excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), morning headache, fatigue, and impaired concentration span. However, snoring occasionally is not a prominent feature of CSA. While OSA and CSA are two different entities, sometimes they coexist, and patients have mixed characteristics. Increased body weight index is associated with an increased risk of OSA; however, patients with CSA are relatively less obese.

Additional symptoms are pertinent to the underlying disease process in patients with hypercapnic central apnea. An interesting clinical observation about the patients with HF is that they often don't recognize or report daytime symptoms despite the objective evidence of sleepiness.[13][14] Increased daytime sympathetic activity can explain this lack of perceived disrupted sleep, which augments alertness and counteracts sleepiness.[15]

A recent study demonstrated an inverse relationship between the degree of subjective daytime sleepiness and mortality risk.[16] Thus, the presumptive diagnosis of sleep apnea should be considered in HF elderly patients with subjective complaints of fatigue even if they lack typical EDS.

Evaluation

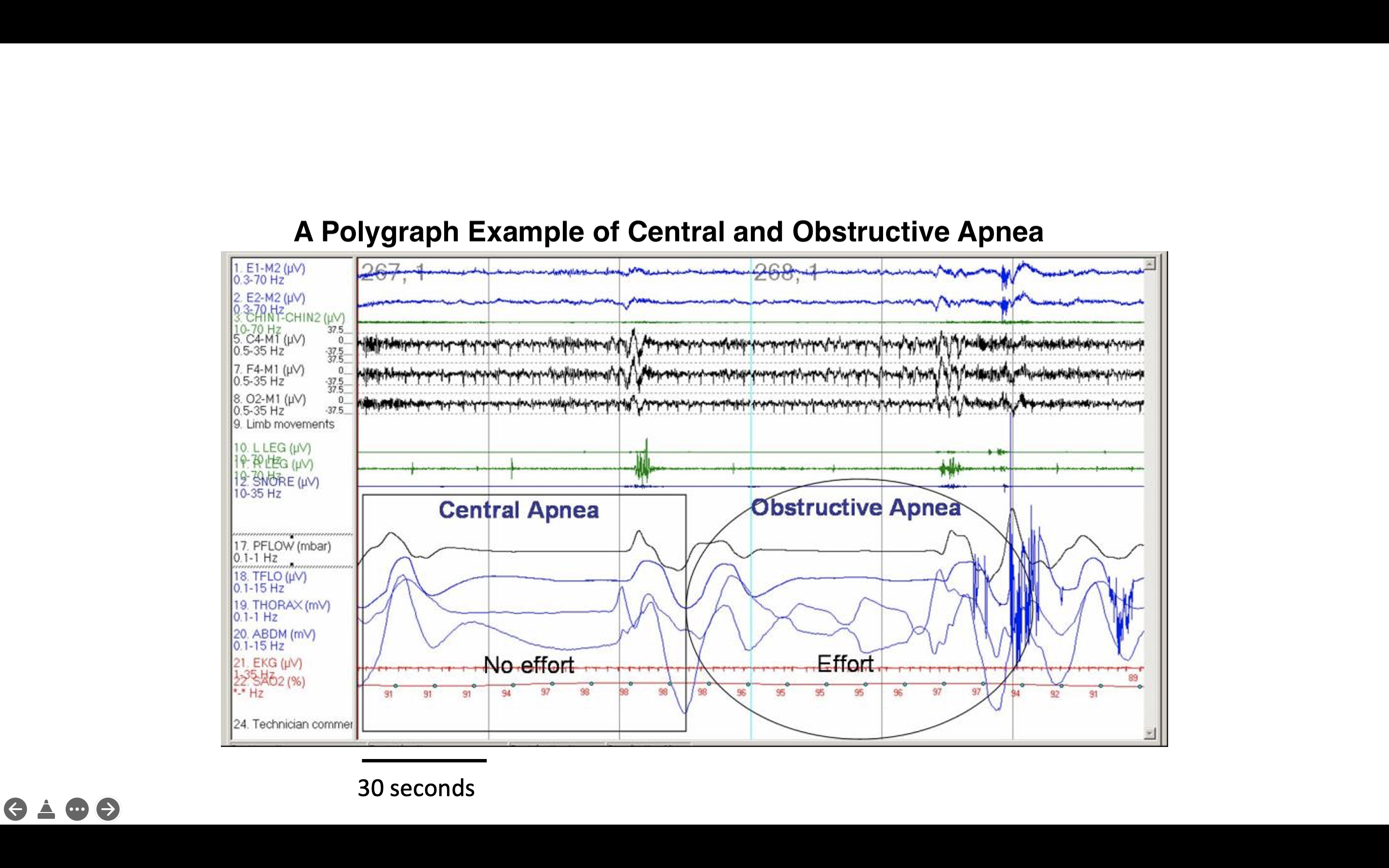

Early detection and diagnosis of CSA can be challenging solely based on self-reported symptoms of disrupted sleep. Nocturnal polysomnography (PSG) is the gold standard diagnostic test in evaluating central apnea is nocturnal polysomnography (PSG). The diagnostic criteria for CSA were published by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) in ICSD-3 [2] and varies according to the type of CSA.[17] It generally requires evidence of recurrent central apneas on PSG recording and exclusion of alternative diagnoses. Central apnea is defined as a cessation of flow during sleep for at least 10 seconds without effort (figure 1).[18]

- Diagnosis of primary CSA can be made if PSG reveals ≥5 central apneas and/or central hypopneas per hour of sleep, with a total number of these central events being >50% of total respiratory events in the apnea-hypopnea index with no evidence of Cheyne-Stokes breathing (CSB).[18] Additionally, there must be at least one complaint related to disrupted sleep, i.e., sleepiness, insomnia, awakening with shortness of breath, snoring, or witnessed apneas.

- Diagnosis of CSA with CSB requires the criteria of primary CSA with three or more consecutive central apneas or hypopneas separated by a crescendo–decrescendo respiratory pattern with a cycle length of ≥40 seconds.

- Diagnosis of treatment-emergent central apnea requires to have a primary diagnosis of OSA (with an apnea-hypopnea index ≥ 5 obstructive respiratory events per hour of sleep) followed by resolution of the obstructive apnea and emergence or persistence of CSA (not explained by the presence of other disease or substance) during positive airway pressure (PAP) titration study.

Treatment / Management

The primary goals in CSA management are to stabilize sleep by suppressing abnormal respiratory events and optimizing the treatment of comorbid conditions. Positive airway pressure (PAP) remains a standard treatment for both central and obstructive apnea that can be delivered as continuous PAP (CPAP), Bi-level PAP therapy (BPAP), and adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV). Apart from PAP devices, additional therapeutic options include supplemental Oxygen, carbon dioxide, and pharmacologic agents. A longitudinal study demonstrated that CPAP and BPAP are more effective for CSA management in HF and opioid use.[19](B2)

The heterogeneity of disease necessitates individualized therapies for the proper management of CSA rather than a homogenous treatment approach. The treatment can include mechanical pressure devices, Oxygen, nerve stimulators, and/or pharmacological therapies.[20]

Mechanical Devices

- CPAP; has been recommended as the first-line therapy for CSA. Available literature and data support CPAP's beneficial effect on CSA.[21][22] It can be explained by its ability to maintain airway patency, stabilizing the compensatory ventilatory output. In concurrent obstructive episodes, CPAP is a reasonable therapeutic option. The Canadian CPAP (CANPAP) trial was the most extensive randomized controlled study to evaluate the effect of CPAP on morbidity and mortality in patients with CSA and HF.[23] The study did reveal a modest reduction in mean apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) to 19 events per hour of sleep without significant effect on mortality. A subsequent post hoc analysis showed a reduction in mortality rate in those patients who responded to CPAP therapy.[24]

- BPAP; It can be a viable option in hypercapnic CSA, especially if the patient is unresponsive to CPAP. Dohi et al. suggested the effectiveness of BPAP in patients with HF and CSA with CSB.[25] BPAP acts to normalize the AHI by increasing ventilation and augmenting alveolar volume. A longitudinal cross-section study also suggested using CPAP and BiPAP to treat opioid-related CSA.[26]

- ASV; is a form of PAP that provides ventilatory support individualized to the patient's effort. A servo-controlled inspiratory pressure is delivered over positive end-expiratory pressure based on the detection of apneas. It remains a therapeutic option for CSA patients with preserved EF and improves AHI and left ventricular EF (LVEF).[17] A multicenter largest trial (SERVE-HF) revealed that the use of ASV was associated with increased mortality in HF patients with reduced EF.[27] Therefore, ASV is not recommended for the treatment of CSA in this particular group of patients. (A1)

Nocturnal oxygen therapy in previous trials has decreased the number of apneic episodes during sleep times for patients with CHF. It also improved NYHA functional class quality of life, and EF was noted at the end of 12-week in patients with central sleep apnea.[28] These findings were confirmed over 52 weeks in a similar trial, ensuring improved quality of life.[29](A1)

Unilateral placement of phrenic nerve stimulators is another treatment option for patients with central sleep apnea. A recent study suggested that such therapy was associated with decreased disease severity and improved quality of life. It also resulted in significant improvement in the arousal index, improved quality of life, and a decreased self-reported daytime sleepiness. These benefits were independent of heart failure status.[30] Peripheral nerve stimulation works by restoring the normal physiological mechanics of breathing.

Different pharmacological agents have been studied as a potential treatment for central sleep apnea. However, these medications remain investigational, and there is no approved pharmacological treatment for CSA. Hypnotics such as triazolam and zolpidem can reduce wakefulness and unstable sleep.[31] These medications may lead to increased total sleep, decreased central apnea index, and a decrease in brief arousals.[31] (A1)

Respiratory stimulants such as acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, work by causing mild metabolic acidosis, resulting in increased respiratory drive decreases the frequency of central apneas.[32] Recently, other medications such as Buspirone [33]and Mirtazapine have been studied.[33][34] Both drugs reduced the susceptibility to developing hypocapnic central apnea in individuals with spinal cord injuries. Theophylline, a non-selective adenosine receptors antagonist, has been used in the context of central sleep apneas in patients with heart failure, and the benefit may be attributed to inhibition of adenosine receptors located in the medulla leading to increasing ventilatory stimulation.[35] A recent experimental study demonstrated that selective adenosine A1 receptor blockade could alleviate the cervical spinal cord injury model.[36](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The number of conditions must be considered and ruled out before establishing the diagnosis of central sleep apnea because of the characteristics of some of these diseases to cause excessive daytime sleepiness along with other symptoms that might contribute to the disruption of sleep. These conditions include:

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Periodic limb movements of sleep

- Narcolepsy

- Obstructive and restrictive lung diseases

- Patients with neuromuscular disease

- Night shift workers and people who have variable sleep routines/patterns

Prognosis

Heart failure patients with CSA and CSB tend to have a worse prognosis, and treatment often includes optimization of heart failure therapy.[37]

Adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) is a therapy modality that delivers servo-controlled inspiratory pressure support on top of expiratory positive airway pressure. A recent study in 2015 showed that in patients with heart failure with reduced EF, ASV was associated with increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality without any significant benefit. There was no improvement in either symptoms or quality of life.[38] There has been reportedly increased mortality in patients with heart failure with reduced EF in whom adaptive servo-ventilation was used.[39]

Complications

Patients with sleep apnea syndrome are at increased risk of systemic complications, including systemic hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, arrhythmias including atrial fibrillation, sleep disturbances accompanied with excessive daytime sleepiness, mood disorders, chronic respiratory failure, narcolepsy, and hypercapnic respiratory failure.[40]

Deterrence and Patient Education

The patients and families need to understand the physiology and mechanism causing sleep apnea. During regular sleep, the air can move through the respiratory tract at a normal rhythm. Still, there is the transient cessation of air movement with resultant reduction in breathing in patients with central sleep apnea because of breathing control and rhythm changes. Central sleep apnea has a long-term impact on health and quality of life. Symptoms may include restless sleep, low energy, difficulty concentrating, memory impairment, and waking up unrested.

The goal standard for diagnosis is a sleep study called polysomnogram that measures breathing effort and airflow, vitals, and blood oxygen level during different stages of sleep. Treatment includes identifying underlying causes and treating any precipitating factors. Ideally, these patients need to be evaluated by a sleep physician.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

For patients with central sleep apnea, a multidisciplinary approach is important to the patient's overall care. This may include a cardiologist in patients with heart failure to appropriately optimize treatment. The role of respiratory therapists and nurses is important in educating patients on proper techniques to use various machines and masks for non-invasive ventilation, which is a cornerstone of management in patients with central sleep apnea. Pharmacists form an integral component in evaluating and identifying any medications that may contribute to the disease progression. Overall, a multidisciplinary approach is essential in managing patients with central sleep apnea.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Video to Play)

References

Sankri-Tarbichi AG, Rowley JA, Badr MS. Expiratory pharyngeal narrowing during central hypocapnic hypopnea. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009 Feb 15:179(4):313-9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200805-741OC. Epub 2008 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 19201929]

Sateia MJ, International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: highlights and modifications. Chest. 2014 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 25367475]

Sankari A, Bascom A, Oomman S, Badr MS. Sleep disordered breathing in chronic spinal cord injury. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2014 Jan 15:10(1):65-72. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3362. Epub 2014 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 24426822]

Sankari A,Bascom AT,Chowdhuri S,Badr MS, Tetraplegia is a risk factor for central sleep apnea. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985). 2014 Feb 1; [PubMed PMID: 24114704]

Javaheri S,Barbe F,Campos-Rodriguez F,Dempsey JA,Khayat R,Javaheri S,Malhotra A,Martinez-Garcia MA,Mehra R,Pack AI,Polotsky VY,Redline S,Somers VK, Sleep Apnea: Types, Mechanisms, and Clinical Cardiovascular Consequences. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017 Feb 21; [PubMed PMID: 28209226]

Bixler EO,Vgontzas AN,Ten Have T,Tyson K,Kales A, Effects of age on sleep apnea in men: I. Prevalence and severity. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1998 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 9445292]

Donovan LM,Kapur VK, Prevalence and Characteristics of Central Compared to Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Analyses from the Sleep Heart Health Study Cohort. Sleep. 2016 Jul 1; [PubMed PMID: 27166235]

Chowdhuri S,Pranathiageswaran S,Loomis-King H,Salloum A,Badr MS, Aging is associated with increased propensity for central apnea during NREM sleep. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985). 2018 Jan 1; [PubMed PMID: 29025898]

Zhou XS,Shahabuddin S,Zahn BR,Babcock MA,Badr MS, Effect of gender on the development of hypocapnic apnea/hypopnea during NREM sleep. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985). 2000 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 10904052]

Sankri-Tarbichi AG,Rowley JA,Badr MS, Inhibition of ventilatory motor output increases expiratory retro palatal compliance during sleep. Respiratory physiology [PubMed PMID: 21334465]

Sankri-Tarbichi AG,Richardson NN,Chowdhuri S,Rowley JA,Safwan Badr M, Hypocapnia is associated with increased upper airway expiratory resistance during sleep. Respiratory physiology [PubMed PMID: 21513820]

Javaheri S, A mechanism of central sleep apnea in patients with heart failure. The New England journal of medicine. 1999 Sep 23; [PubMed PMID: 10498490]

Hastings PC,Vazir A,O'Driscoll DM,Morrell MJ,Simonds AK, Symptom burden of sleep-disordered breathing in mild-to-moderate congestive heart failure patients. The European respiratory journal. 2006 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 16585081]

Redeker NS,Muench U,Zucker MJ,Walsleben J,Gilbert M,Freudenberger R,Chen M,Campbell D,Blank L,Berkowitz R,Adams L,Rapoport DM, Sleep disordered breathing, daytime symptoms, and functional performance in stable heart failure. Sleep. 2010 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 20394325]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTaranto Montemurro L,Floras JS,Millar PJ,Kasai T,Gabriel JM,Spaak J,Coelho FMS,Bradley TD, Inverse relationship of subjective daytime sleepiness to sympathetic activity in patients with heart failure and obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2012 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 23303285]

Kasai T,Taranto Montemurro L,Yumino D,Wang H,Floras JS,Newton GE,Mak S,Ruttanaumpawan P,Parker JD,Bradley TD, Inverse relationship of subjective daytime sleepiness to mortality in heart failure patients with sleep apnoea. ESC heart failure. 2020 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 32608195]

Aurora RN,Chowdhuri S,Ramar K,Bista SR,Casey KR,Lamm CI,Kristo DA,Mallea JM,Rowley JA,Zak RS,Tracy SL, The treatment of central sleep apnea syndromes in adults: practice parameters with an evidence-based literature review and meta-analyses. Sleep. 2012 Jan 1; [PubMed PMID: 22215916]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBerry RB,Brooks R,Gamaldo C,Harding SM,Lloyd RM,Quan SF,Troester MT,Vaughn BV, AASM Scoring Manual Updates for 2017 (Version 2.4). Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2017 May 15; [PubMed PMID: 28416048]

Sadeghi Y,Sedaghat M,Majedi MA,Pakzad B,Ghaderi A,Raeisi A, Comparative Evaluation of Therapeutic Approaches to Central Sleep Apnea. Advanced biomedical research. 2019; [PubMed PMID: 30993083]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJamil SM,Owens RL,Lipford MC,Shafazand S,Marron RM,Vega Sanchez ME,Lam MT,Sunwoo BY,Schmickl C,Orr JE,Sharma S,Sankari A,Javaheri S,Bertisch S,Dupuy-McCauley K,Kolla B,Imayama I,Prasad B,Guzman E,Hayes MM,Wang T, ATS Core Curriculum 2020. Adult Sleep Medicine. ATS scholar. 2020 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 33870314]

Hoffstein V,Slutsky AS, Central sleep apnea reversed by continuous positive airway pressure. The American review of respiratory disease. 1987 May; [PubMed PMID: 3555196]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSin DD,Logan AG,Fitzgerald FS,Liu PP,Bradley TD, Effects of continuous positive airway pressure on cardiovascular outcomes in heart failure patients with and without Cheyne-Stokes respiration. Circulation. 2000 Jul 4; [PubMed PMID: 10880416]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBradley TD,Logan AG,Kimoff RJ,Sériès F,Morrison D,Ferguson K,Belenkie I,Pfeifer M,Fleetham J,Hanly P,Smilovitch M,Tomlinson G,Floras JS,CANPAP Investigators., Continuous positive airway pressure for central sleep apnea and heart failure. The New England journal of medicine. 2005 Nov 10; [PubMed PMID: 16282177]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceArzt M,Floras JS,Logan AG,Kimoff RJ,Series F,Morrison D,Ferguson K,Belenkie I,Pfeifer M,Fleetham J,Hanly P,Smilovitch M,Ryan C,Tomlinson G,Bradley TD,CANPAP Investigators., Suppression of central sleep apnea by continuous positive airway pressure and transplant-free survival in heart failure: a post hoc analysis of the Canadian Continuous Positive Airway Pressure for Patients with Central Sleep Apnea and Heart Failure Trial (CANPAP). Circulation. 2007 Jun 26; [PubMed PMID: 17562959]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDohi T,Kasai T,Narui K,Ishiwata S,Ohno M,Yamaguchi T,Momomura S, Bi-level positive airway pressure ventilation for treating heart failure with central sleep apnea that is unresponsive to continuous positive airway pressure. Circulation journal : official journal of the Japanese Circulation Society. 2008 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 18577818]

Schoebel C,Ghaderi A,Amra B,Soltaninejad F,Penzel T,Fietze I, Comparison of Therapeutic Approaches to Addicted Patients with Central Sleep Apnea. Tanaffos. 2018 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 30915131]

Cowie MR,Woehrle H,Wegscheider K,Angermann C,d'Ortho MP,Erdmann E,Levy P,Simonds AK,Somers VK,Zannad F,Teschler H, Adaptive Servo-Ventilation for Central Sleep Apnea in Systolic Heart Failure. The New England journal of medicine. 2015 Sep 17; [PubMed PMID: 26323938]

Sakakibara M,Sakata Y,Usui K,Hayama Y,Kanda S,Wada N,Matsui Y,Suto Y,Shimura S,Tanabe T, Effectiveness of short-term treatment with nocturnal oxygen therapy for central sleep apnea in patients with congestive heart failure. Journal of cardiology. 2005 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 16127894]

Sasayama S,Izumi T,Matsuzaki M,Matsumori A,Asanoi H,Momomura S,Seino Y,Ueshima K,CHF-HOT Study Group., Improvement of quality of life with nocturnal oxygen therapy in heart failure patients with central sleep apnea. Circulation journal : official journal of the Japanese Circulation Society. 2009 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 19448327]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFudim M,Spector AR,Costanzo MR,Pokorney SD,Mentz RJ,Jagielski D,Augostini R,Abraham WT,Ponikowski PP,McKane SW,Piccini JP, Phrenic Nerve Stimulation for the Treatment of Central Sleep Apnea: A Pooled Cohort Analysis. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2019 Dec 15; [PubMed PMID: 31855160]

Bonnet MH,Dexter JR,Arand DL, The effect of triazolam on arousal and respiration in central sleep apnea patients. Sleep. 1990 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 2406849]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGinter G, Sankari A, Eshraghi M, Obiakor H, Yarandi H, Chowdhuri S, Salloum A, Badr MS. Effect of acetazolamide on susceptibility to central sleep apnea in chronic spinal cord injury. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985). 2020 Apr 1:128(4):960-966. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00532.2019. Epub 2020 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 32078469]

Prowting J, Maresh S, Vaughan S, Kruppe E, Alsabri B, Badr MS, Sankari A. Mirtazapine reduces susceptibility to hypocapnic central sleep apnea in males with sleep-disordered breathing: a pilot study. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985). 2021 Jul 1:131(1):414-423. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00838.2020. Epub 2021 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 34080920]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMaresh S, Prowting J, Vaughan S, Kruppe E, Alsabri B, Yarandi H, Badr MS, Sankari A. Buspirone decreases susceptibility to hypocapnic central sleep apnea in chronic SCI patients. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985). 2020 Oct 1:129(4):675-682. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00435.2020. Epub 2020 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 32816639]

Javaheri S,Parker TJ,Wexler L,Liming JD,Lindower P,Roselle GA, Effect of theophylline on sleep-disordered breathing in heart failure. The New England journal of medicine. 1996 Aug 22; [PubMed PMID: 8678934]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSankari A, Minic Z, Farshi P, Shanidze M, Mansour W, Liu F, Mao G, Goshgarian HG. Sleep disordered breathing induced by cervical spinal cord injury and effect of adenosine A1 receptors modulation in rats. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985). 2019 Dec 1:127(6):1668-1676. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00563.2019. Epub 2019 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 31600096]

Terziyski K,Draganova A, Central Sleep Apnea with Cheyne-Stokes Breathing in Heart Failure - From Research to Clinical Practice and Beyond. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2018; [PubMed PMID: 29411336]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCowie MR,Woehrle H,Wegscheider K,Vettorazzi E,Lezius S,Koenig W,Weidemann F,Smith G,Angermann C,d'Ortho MP,Erdmann E,Levy P,Simonds AK,Somers VK,Zannad F,Teschler H, Adaptive servo-ventilation for central sleep apnoea in systolic heart failure: results of the major substudy of SERVE-HF. European journal of heart failure. 2018 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 29193576]

Iftikhar IH,Khayat RN, Central sleep apnea treatment in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a network meta-analysis. Sleep [PubMed PMID: 34698980]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChaudhary BA,Speir WA Jr, Sleep apnea syndromes. Southern medical journal. 1982 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 7034220]