Introduction

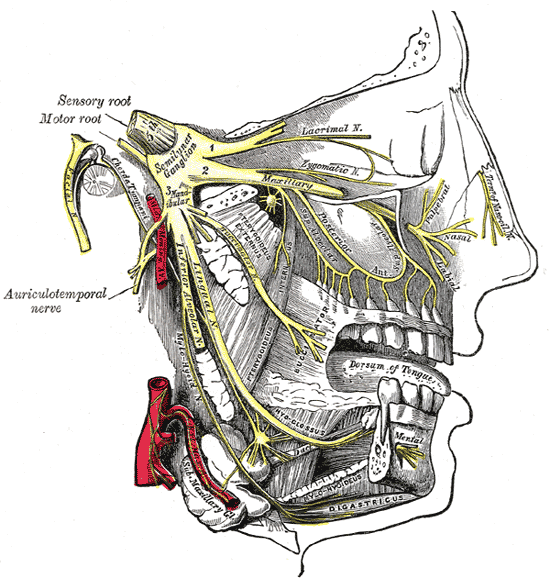

The lingual nerve is a sensory nerve that arises from the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V). The lingual nerve is often in a common stem with the inferior alveolar nerve after the mandibular division enters the infratemporal fossa through the foramen ovale [1]. The lingual nerve separates from the inferior alveolar nerve and then descends anteriorly into the oral cavity. It travels adjacent to the medial surface of the mandibular ramus in the third molar region. As it does so, it innervates the mucous membrane of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, the floor of the oral cavity, and the adjacent lingual gingiva [2]. Understanding the anatomy of the lingual nerve is crucial for performing safe surgical procedures in its area of distribution, mainly when extracting impacted mandibular third molars, as lingual nerve injury is one of the most serious complications of this procedure [1].

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

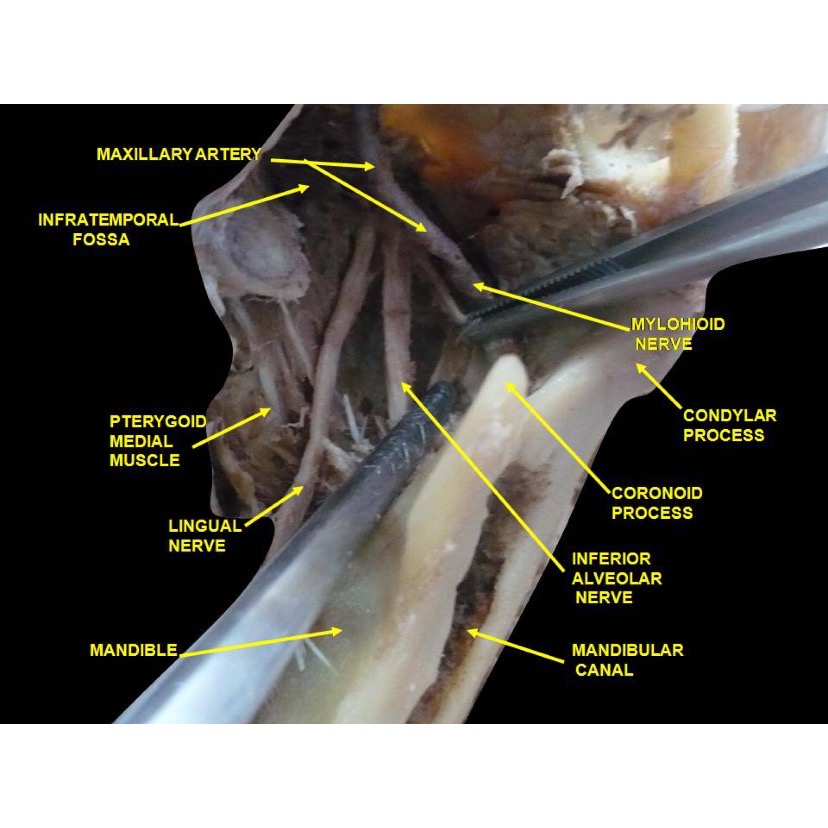

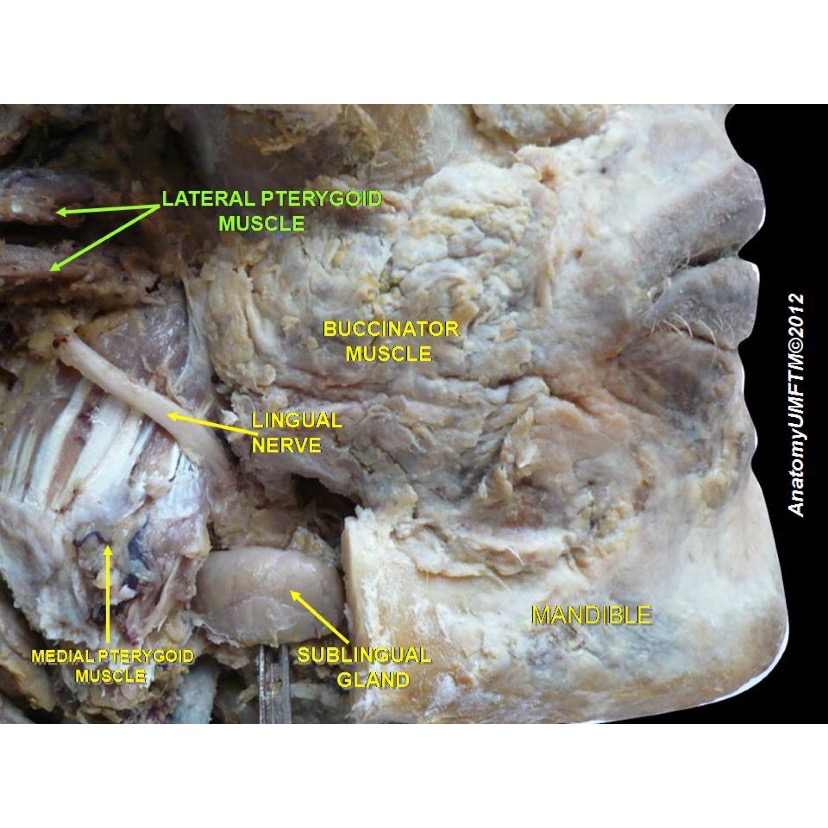

The mandibular nerve is a mixed nerve containing afferent and efferent fibers and leaves the cranium through the foramen ovale [1]. The lingual nerve arises from the posterior branch of the mandibular nerve high in the infratemporal fossa and passes between the tensor veli palatini and lateral pterygoid muscles. It then emerges from between the lateral and medial pterygoid muscles anterior to the inferior alveolar nerve [3]. The nerve passes between the lateral surface of the medial pterygoid muscle and the mandibular ramus en route to the oral cavity.

The lingual nerve reaches the oral cavity passing below the inferior border of the superior constrictor muscle in close proximity to the pterygomandibular raphe's attachment in the mandible. It courses anteriorly and inferiorly adjacent to the medial aspect of the mandibular ramus traveling through the vicinity of the mandibular third molar's roots. This relation is important during wisdom tooth extraction.

The lingual nerve continues to run anteriorly, but now it turns medially to reach the tongue, traveling between the hyoglossus and mylohyoid muscles. The nerve extends to the hyoglossus's lateral aspect and gets to its front border. The nerve loops under the submandibular duct as it passes toward the apex of the tongue [2]. The lingual nerve terminal branches provide somatic afferent innervation to the mucosa of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue [4]. During its trajectory through the floor of the mouth, the lingual nerve gives branches to innervate the lingual gingiva of the ipsilateral mandibular teeth and the floor of the mouth [3].

Embryology

The trigeminal nerve neurons originate from the neural crest cells from the cranial mesencephalon and caudal diencephalon.

Nerves

The chorda tympani nerve (branch of the facial nerve) joins the lingual nerve below the skull near the lower border of the lateral pterygoid muscle within the pterygomandibular space [3]. The lingual nerve transports special visceral afferent (SVA) fibers from the chorda tympani responsible for taste perception in the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, and general visceral efferent (GVE) fibers responsible for secretory and motor innervation of the sublingual and submandibular glands [3]. These preganglionic fibers synapse in the submandibular ganglion, suspended from the lingual nerve, and the postganglionic parasympathetic fibers enter the glands [5]. The lingual nerve also has anterior, middle, and posterior communicating branches with the hypoglossal nerve [1].

Other sensory branches of the mandibular nerve are the auriculotemporal nerve, the buccal nerve, and the inferior alveolar nerve; however, the inferior alveolar nerve also gives off a small motor branch, the mylohyoid nerve.

Physiologic Variants

Variations in the termination of the lingual nerve, specifically in its branching pattern, have been described. The lingual nerve has been found to divide into between one and four branches at its terminal end in the tongue [2]. The most common type of branching seen at the termination of the lingual nerve is two branches. Another variation is the distance the lingual nerve travels on the floor of the mouth before turning medially toward the tongue. Most lingual nerves are found to deviate toward the tongue from the floor of the mouth between the mesial of the first molar and the distal of the second molar [2]. The lingual nerve can also have connections with the mylohyoid nerves, occurring in up to 12.50% of cases [6]. When considering surgery in the infratemporal fossa or floor of the oral cavity for a patient, these possible variations in the course of the lingual nerve are extremely important to consider.

Surgical Considerations

The lingual nerve is one of the two nerves most commonly injured during oral surgery with the other being the inferior alveolar nerve [3]. Numerous procedures have been thought to cause lingual nerve damage, including mandibular resection, extraction of a third molar tooth, surgery of the salivary glands, excision of tumors, and lingual flap retraction [7][8].

The lingual nerve may also suffer an injury during suspension laryngoscopy, a procedure commonly done in otorhinolaryngology. The risk of damage to the nerve increases during this procedure when there is difficulty during the surgery and longer operating times [9].

An increase in the number of second molar implants has also increased the risk of injury to the nerve [3]. However, the lingual nerve most commonly gets damaged during inferior alveolar nerve block injections and third molar tooth removals [3][10]. Reports indicate that damage to this nerve occurs during the removal of the third molar between 0 and 23% of the time [11][12]. The wide variation in reported frequencies of this injury may be in part due to the variations seen in the course of the lingual nerve. Potential mechanisms for preventing lingual nerve injury during third molar surgery include avoiding lingual flap elevation and conducting tooth sectioning [8][13].

Injury to the lingual nerve most often results in temporary symptoms, including hyperaesthesia (increased sensitivity), anesthesia (complete loss of feeling), hypoaesthesia (diminished sensitivity), and dysaesthesia (painful sensation) in the anterior two-thirds of the tongue [7]. Other complications from lingual injury include mechanical (due to biting) and thermal trauma if the tongue and lip are affected by paraesthesia, speaking difficulty, problems with tooth brushing, and sleep difficulty when there is allodynia [14]. Reports indicate that the nerve typically repairs itself within 6 months of damage [15]. If the nerve is injured during dental work and does not repair itself, treatment can be given, including physiotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and stellate ganglion block [16]. It can sometimes be repaired with a direct epineural repair or indirect (graft) neurorrhaphy, most commonly using the sural nerve [4].

The lingual nerve can also be the target for a nerve block during certain pathological conditions and procedures. Specifically, a lingual nerve block has been found to be useful for procedures and conditions occurring within the soft tissues of the tongue, including minor infections, traumatic lacerations, and pathological lesions [17]. Benefits of a lingual nerve block instead of an inferior alveolar nerve block include avoiding unnecessary anesthesia of the lip, chin, and buccal soft tissues [17]. This difference is an especially important consideration in patients with mental deficits, children, and the elderly, who present with traumatic lip biting [17].

Clinical Significance

As the lingual nerve travels from the infratemporal fossa to underneath the tongue, it can become entrapped by several structures, including fibers of the lateral pterygoid muscle, pterygospinous or pterygoalar ligaments, and the lateral pterygoid plate. Entrapment of the lingual nerve can cause numbness and loss of taste from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, loss of sensation from the lingual gingiva, and pain with speech disorders [18].

Smoking can impact the somatosensory function of the lingual nerve, causing degeneration of the nerve fibers. Studies have indicated that smokers have a loss of non-noxious thermal stimuli, but not loss of sensation of mechanical or painful thermal stimuli [19]. A hypothesis to the cause of this sensory change is the degeneration of the thermoreceptors [19].

Lingual Nerve Injury during Dental Procedures

The lingual nerve can be damaged due to dental procedures, nerve blocks, or pathological tooth complications. The most common dental reason for lingual nerve injury is the extraction of mandibular wisdom teeth, followed by the administration of inferior alveolar nerve block and endodontic or periodontal complications [14]. A study showed that the lingual nerve was damaged in 89% of paraesthesia cases after the inferior alveolar nerve block [20].

Several reasons are believed to play a role in the lingual nerve's high susceptibility during the IAN block, which is even higher than the inferior alveolar nerve's. The lingual nerve tends to be unifascicular and has a thick perineurium, making it less capable of supporting trauma from edema and hemorrhage [14]. Furthermore, it is located at only 5 to 6 mm below the mucosa's surface and lacks osseous protection [14][21][22]. Another reason could be that the lingual nerve stretches taut when opening the mouth during the administration of the block and is fixed underneath the interpterygoid fascia. It may not be capable of moving when contacted by the needle, resulting in the nerve being directly penetrated by the needle, with the consequent damage [23].

When the lingual nerve is affected during a traumatic incident, the chorda tympani (facial nerve branch) may also be damaged, and dysgeusia and xerostomia may develop [14].

Other Issues

The lingual nerve is more likely to be damaged during the administration of the inferior alveolar nerve block than the inferior alveolar nerve. Even though neural injuries are rare, it is imperative that dental professionals have deep knowledge of the anatomy of the lingual nerve and an understanding of the IAN block technique to avoid complications.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Trigeminal Nerve Divisions. This illustration shows the distribution of the 3 trigeminal nerve divisions. The ophthalmic division gives rise to the lacrimal nerve and supplies the superior third of the face and skull. The maxillary division supplies the midfacial region. The mandibular division innervates the muscles of mastication and gathers sensory information from the lower third of the face. The trigeminal nerve's semilunar ganglion and sensory and motor roots are also shown.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kikuta S, Iwanaga J, Kusukawa J, Tubbs RS. An anatomical study of the lingual nerve in the lower third molar area. Anatomy & cell biology. 2019 Jun:52(2):140-142. doi: 10.5115/acb.2019.52.2.140. Epub 2019 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 31338230]

Al-Amery SM, Nambiar P, Naidu M, Ngeow WC. Variation in Lingual Nerve Course: A Human Cadaveric Study. PloS one. 2016:11(9):e0162773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162773. Epub 2016 Sep 23 [PubMed PMID: 27662622]

Benninger B, Kloenne J, Horn JL. Clinical anatomy of the lingual nerve and identification with ultrasonography. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 2013 Sep:51(6):541-4. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.10.014. Epub 2012 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 23182453]

Shimoo Y, Yamamoto M, Suzuki M, Yamauchi M, Kaketa A, Kasahara M, Serikawa M, Kitamura K, Matsunaga S, Abe S. Anatomic and Histological Study of Lingual Nerve and Its Clinical Implications. The Bulletin of Tokyo Dental College. 2017:58(2):95-101. doi: 10.2209/tdcpublication.2016-0010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28724864]

Takezawa K, Kageyama I. Nerve fiber analysis on the morphology of the lingual nerve. Anatomical science international. 2015 Sep:90(4):298-302. doi: 10.1007/s12565-014-0267-5. Epub 2014 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 25467528]

Zhan C, Yuan Z, Qu R, Zou L, He S, Li Z, Liu C, Xiao Z, Ouyang J, Dai J. Should we pay attention to the aberrant nerve communication between the lingual and mylohyoid nerves? The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 2019 May:57(4):317-322. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2019.03.003. Epub 2019 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 30940405]

Dias GJ, de Silva RK, Shah T, Sim E, Song N, Colombage S, Cornwall J. Multivariate assessment of site of lingual nerve. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 2015 Apr:53(4):347-51. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2015.01.011. Epub 2015 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 25662169]

Pippi R, Spota A, Santoro M. Prevention of Lingual Nerve Injury in Third Molar Surgery: Literature Review. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2017 May:75(5):890-900. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2016.12.040. Epub 2017 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 28142010]

Ozdamar OI, Uzun L, Acar GO, Tekin M, Kokten N, Celik S. Risk Factors for Lingual Nerve Injury Associated With Suspension Laryngoscopy. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2019 Jul:128(7):633-639. doi: 10.1177/0003489419835854. Epub 2019 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 30841712]

Sittitavornwong S, Babston M, Denson D, Zehren S, Friend J. Clinical Anatomy of the Lingual Nerve: A Review. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2017 May:75(5):926.e1-926.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2017.01.009. Epub 2017 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 28189657]

Chiapasco M, De Cicco L, Marrone G. Side effects and complications associated with third molar surgery. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1993 Oct:76(4):412-20 [PubMed PMID: 8233418]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMiddlehurst RJ, Barker GR, Rood JP. Postoperative morbidity with mandibular third molar surgery: a comparison of two techniques. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 1988 Jun:46(6):474-6 [PubMed PMID: 3164052]

Shepherd JP. Lingual nerve retraction increases the risk of temporary lingual nerve damage during mandibular third molar surgery. Evidence-based dentistry. 2006:7(2):47 [PubMed PMID: 16858382]

Tan VL, Andrawos A, Ghabriel MN, Townsend GC. Applied anatomy of the lingual nerve: relevance to dental anaesthesia. Archives of oral biology. 2014 Mar:59(3):324-35. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2013.12.002. Epub 2013 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 24581856]

Chossegros C, Guyot L, Cheynet F, Belloni D, Blanc JL. Is lingual nerve protection necessary for lower third molar germectomy? A prospective study of 300 procedures. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2002 Dec:31(6):620-4 [PubMed PMID: 12521318]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceShintani Y, Nakanishi T, Ueda M, Mizobata N, Tojyo I, Fujita S. Comparison of Subjective and Objective Assessments of Neurosensory Function after Lingual Nerve Repair. Medical principles and practice : international journal of the Kuwait University, Health Science Centre. 2019:28(3):231-235. doi: 10.1159/000497610. Epub 2019 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 30726857]

Balasubramanian S, Paneerselvam E, Guruprasad T, Pathumai M, Abraham S, Krishnakumar Raja VB. Efficacy of Exclusive Lingual Nerve Block versus Conventional Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block in Achieving Lingual Soft-tissue Anesthesia. Annals of maxillofacial surgery. 2017 Jul-Dec:7(2):250-255. doi: 10.4103/ams.ams_65_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29264294]

Piagkou M, Demesticha T, Piagkos G, Georgios A, Panagiotis S. Lingual nerve entrapment in muscular and osseous structures. International journal of oral science. 2010 Dec:2(4):181-9. doi: 10.4248/IJOS10063. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21404967]

Rittich AB, Ellrich J, Said Yekta-Michael S. Assessment of lingual nerve functions after smoking cessation. Acta odontologica Scandinavica. 2017 Jul:75(5):338-344. doi: 10.1080/00016357.2017.1308551. Epub 2017 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 28372503]

Garisto GA, Gaffen AS, Lawrence HP, Tenenbaum HC, Haas DA. Occurrence of paresthesia after dental local anesthetic administration in the United States. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 2010 Jul:141(7):836-44 [PubMed PMID: 20592403]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKhoury J, Mihailidis S, Ghabriel M, Townsend G. Anatomical relationships within the human pterygomandibular space: Relevance to local anesthesia. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2010 Nov:23(8):936-44. doi: 10.1002/ca.21047. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20949494]

Ogle OE, Mahjoubi G. Local anesthesia: agents, techniques, and complications. Dental clinics of North America. 2012 Jan:56(1):133-48, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2011.08.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22117947]

Harn SD, Durham TM. Incidence of lingual nerve trauma and postinjection complications in conventional mandibular block anesthesia. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 1990 Oct:121(4):519-23 [PubMed PMID: 2212345]