Introduction

Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome is a congenital cardiac preexcitation syndrome that arises from abnormal cardiac electrical conduction through an accessory pathway that can result in symptomatic and life-threatening arrhythmias. The hallmark electrocardiographic (ECG) finding of WPW pattern or preexcitation consists of a short PR interval and prolonged QRS with an initial slurring upstroke (“delta” wave) in the presence of sinus rhythm. The term WPW syndrome is reserved for an ECG pattern consistent with the above-described findings along with the coexistence of a tachyarrhythmia and clinical symptoms of tachycardia such as palpitations, episodic lightheadedness, presyncope, syncope, or even cardiac arrest.

The normal heart consists of two electrically insulated units, the atria and the ventricles. These units are connected by a conduction system that allows for normal cardiac synchrony and function. The cardiac electrical potential originates from the sinoatrial node of the right atrium and propagates through the atria to the atrioventricular (AV) node. The action potential is delayed in the AV node and is then quickly transmitted through the His-Purkinje system to the ventricular myocytes allowing for rapid ventricular depolarization and synchronized contraction.[1] Patients with WPW syndrome have an accessory pathway that violates the electrical isolation of the atria and ventricles, which can allow electrical impulses to bypass the AV node. In some settings, this pathway can result in the transmission of abnormal electrical impulses leading to malignant tachyarrhythmias. The ECG findings of the WPW pattern are caused by the fusion of ventricular preexcitation through the accessory pathway and normal electrical conduction. Most patients with WPW pattern will never develop arrhythmia and will remain asymptomatic. Some accessory pathways will not manifest the described typical ECG findings, and as a result, some patients can develop a tachyarrhythmia with no prior ECG evidence that the pathway exists. These are referred to as concealed bypass tracts.[2][3][4]

In the early 1900s, Frank Wilson and Alfred Wedd are thought to have first described ECG patterns that would later be recognized as a WPW pattern. In 1930, Louis Wolff, Sir John Parkinson, and Dr. Paul Dudley White published a case series consisting of 11 patients who experienced paroxysmal tachycardia associated with an underlying ECG pattern of sinus rhythm with short PR and bundle branch block/wide QRS. This phenomenon was subsequently named as Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome. The electrocardiographic features of preexcitation were first correlated with anatomic evidence of anomalous conducting tissue or bypass tracts in 1943.[5][6]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

WPW pattern arises from the fusion of ventricular preexcitation through the accessory pathway and normal electrical conduction through the AV node. This accessory pathway is thought to arise from chamber myocardium during improper early atrial and ventricular folding in cardiac embryogenesis. As a result, electrically conductive myocardial bundles violate the normal electrical insulation of the atrium and ventricle, forming the accessory pathway.[1][7] This pathway usually has non-decremental or non-delayed conduction, which is in contrast to the properties of the normal AV node. The electrical conducting characteristics of the accessory pathway can vary and depend upon factors such as the speed of conduction, direction of conduction, and refractory period. These characteristics, along with location and number of pathways, will determine how the pathway may be involved in the initiation or transmission of an arrhythmia leading to WPW syndrome.[8][9]

Epidemiology

The natural history of asymptomatic WPW patients has been speculated from the available data on symptomatic WPW patients and from those who have been incidentally discovered to have a WPW ECG pattern. In large-scale population-based studies involving pediatric and adult populations, the general prevalence of WPW has been estimated between 1 to 3 per 1000 individuals (0.1 to 0.3 %). Identification of the truly asymptomatic patients with WPW pattern is difficult, as these individuals by definition are those who have no clinical symptoms. A general estimate by experts suggests that about 65% of adolescents and 40% of individuals over 30 years with a WPW pattern on a resting ECG are asymptomatic. The incidence of patients with the WPW pattern progressing to arrhythmia is thought to be around 1% to 2% per year, and WPW syndrome prevalence peaks from age 20 to 24.[10][11][2]

Familial studies have shown a slightly higher incidence of WPW, about 0.55% among first-degree relatives of an index patient with WPW. A familial form of WPW syndrome has been observed with a missense mutation in the PRAKAG2 gene leading to an increase in prevalence to 3.4% in first-degree relatives, and the condition is associated with congenital structural heart disease including Ebstein anomaly and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.[12][13]

Pathophysiology

WPW ECG pattern is caused by abnormal electrical conduction through an accessory pathway that bypasses the normal cardiac conduction system. This accessory pathway allows cardiac electrical activity to bypass the atrioventricular node conduction delay, and arrive early at the ventricle, leading to premature ventricular depolarization. This preexcitation also bypasses the fast conducting His-Purkinje system and results in early but slowly propagated ventricular depolarization, which gives rise to the ECG pattern of a short PR interval with a “slurred” start to the QRS complex termed a delta wave. The remainder of a normal QRS obliterates this delta wave as the normal cardiac conduction catches up following AV node delay and fast conduction through the His-Purkinje system.

There are two ways in which an accessory pathway can lead to WPW syndrome. The pathway can either initiate and maintain an arrhythmia or allow conduction of an arrhythmia generated elsewhere. The first type occurs when a circuit is formed between the normal conduction system of the heart and the accessory pathway (or two or more accessory pathways), allowing for atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT). An incorrectly timed extra electrical impulse can lead to a recurring cycle between the atria, AV node, ventricles, and the accessory pathway. Orthodromic AVRT occurs when conduction progresses from the atria with antegrade conduction through the AV node to the ventricle and retrograde conduction through the accessory pathway. This will usually result in a narrow complex QRS as the His-Purkinje system is used unless aberrant conduction is present. Antidromic AVRT is the opposite with antegrade conduction passing from the atria through the accessory pathway to the ventricle and retrograde conduction back up the AV node and is usually associated with a wide complex QRS.

The other way an accessory pathway can lead to arrhythmia is by allowing conduction of an arrhythmia that is generated elsewhere to propagate to a portion of the heart that would normally be electrically insulated from this arrhythmia. The accessory pathway is typically comprised of myocardial tissue and usually has non-decremental or non-delayed conduction allowing immediate ventricular activation. This non-decremental conduction property predisposes patients with WPW syndrome to sudden cardiac death. This occurs due to rapid ventricular rates in conditions with rapid atrial depolarization, such as atrial fibrillation (AF) or atrial flutter. These fast ventricular rates can degenerate into ventricular fibrillation (VF) and cardiac arrest.[7][14][15][16][17]

History and Physical

Patients with a WPW pattern who have never developed an arrhythmia will be asymptomatic, and therefore, their history and physical exam will be mostly unremarkable. Prior ECG may have diagnosed the pattern, and the patient may be aware of their condition, but some accessory pathway conduction is transient or concealed, which may lead to prior normal or intermittently normal ECGs. Patients with WPW pattern may have a family history of WPW pattern or syndrome.

Patients with WPW pattern who develop a tachyarrhythmia will often experience symptoms associated with the arrhythmia including palpitations, chest pain, dyspnea, dizziness, lightheadedness, presyncope, syncope, collapse, and/or sudden death. The history will be notable for these symptoms, which may be episodic and resolved, or ongoing at presentation if the arrhythmia persists. Physical exam should be focused on the patient's cardiovascular, pulmonary perfusion status, and neurological exam and may be completely normal if the arrhythmia has resolved. A persisting arrhythmia will usually be symptomatic, and vitals signs will be notable for tachycardia. Blood pressure may range from normal or elevated to hypotension depending on the severity of the tachyarrhythmia, comorbidities, and the patient's ability to compensate for the arrhythmia. Respiratory rate will vary based on the patient's level of distress and the ability to maintain perfusing blood pressure. The physical exam will again vary depending on the severity of the arrhythmia. The cardiac exam will demonstrate a regular or irregular tachycardia. The remainder of the physical exam may be normal or show signs of discomfort, distress, hypoperfusion, cardiogenic shock, and unresponsiveness depending on the severity of the arrhythmia.[16][14][18][19]

Evaluation

WPW pattern is a constellation of electrocardiographic findings, so initial evaluation relies on a surface electrocardiogram. The ECG will show a short PR interval (<120 ms), prolonged QRS complex (>120 ms), and a QRS morphology consisting of a slurred delta wave. The preexcitation of the ventricle causes this morphology through the accessory pathway that forms a fusion complex with the normal QRS complex arising from normal cardiac conduction. The absence of this pattern does not rule out the presence of an accessory pathway since some pathways are only capable of conducting impulses under certain conditions or in a retrograde direction. Such a pathway could only conduct from the ventricle to the atrium and would not cause ventricular preexcitation during normal sinus beats. This concealed accessory pathway will only be evident on ECG during an electrical impulse generated in the ventricle, such as a premature ventricular contraction or ventricular pacing.

Recommendations for further evaluation, risk stratification, electrophysiologic study, and accessory pathway ablation for asymptomatic patients with WPW pattern vary depending on age, risk factors, history of symptoms, comorbidities, baseline ECG pattern, as well as a personal and expert opinion. In general, young, healthy patients without comorbid conditions or significant risk factors who have the WPW pattern on ECG but are asymptomatic and without a history of suspected tachyarrhythmia are likely safe for watchful waiting with primary care and or cardiology follow up. Patients who are at higher risk for arrhythmia should be referred for close cardiology follow up for the discussion of risk stratification testing and/or electrophysiologic study with accessory pathway mapping and possible ablation.[15][8][16] It is also important to note that since the WPW pattern changes the baseline morphology of the ECG, the diagnosis of conditions that rely on ECG criteria may be altered in patients with the WPW pattern. Further testing, an adaptation of ECG diagnostic criteria, or expert consultation may be needed in these cases.[20]

Patients that present with a symptomatic tachyarrhythmia or an episode concerning recent arrhythmia will require an ECG to assess current cardiac rate, rhythm, and morphology but will also require further evaluation. The patient who presents with an acute tachyarrhythmia can be evaluated and managed following the "2010 American Heart Association guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care." This evaluation involves assessing the appropriateness of the clinical condition while obtaining vital signs, including heart rate, blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and placing the patient on the cardiac monitor to assess the cardiac rhythm. If available, history and prior medical information should be obtained to assess for baseline ECG, prior episodes of tachyarrhythmias, and family members with WPW syndrome or sudden cardiac death. History of current symptoms, including ischemic chest discomfort and events leading up to arrhythmia, should be obtained. Mental status, cardiovascular, and pulmonary exams should be focused to assess for acute altered mental status, signs of shock, or acute heart failure, which would be concerning for hemodynamic instability; if identified, the patient should undergo electrical cardioversion. The hemodynamically stable patient should be further evaluated with 12 lead ECG to assess the cardiac rhythm. Imaging and laboratory evaluation should be tailored to the clinical situation and assess for concomitant or provocating clinical conditions and evidence of end-organ dysfunction as a result of the tachyarrhythmia. These studies may include chest radiography, echocardiography, complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, cardiac enzymes, BNP, thyroid function, venous or arterial blood gas as well as further testing to assess other metabolic or comorbid conditions based on the clinical setting.[16][19][18]

Treatment / Management

Asymptomatic patients with WPW pattern do not require any immediate treatment. It may be beneficial for them to undergo evaluation by a cardiologist or electrophysiologist to try to determine the risk of the patient developing a tachyarrhythmia. Patients deemed to be at high risk may benefit from preventative antiarrhythmic medications or prophylactic accessory pathway ablation depending on their level of risk, the type and characteristics of the pathway, their cardiac comorbidities, and other medical conditions. In these cases, the risk of developing a dangerous arrhythmia must be weighed against the benefits and risks of medications and invasive interventions.

In general, patients with asymptomatic WPW pattern are considered at low-risk of a cardiac arrest. Those patients who have had a cardiac arrest usually almost always experience preceding tachycardia related symptoms. Thus, most asymptomatic patients may be managed by reassurance and close watchful clinical monitoring. Patients may be advised to notify their clinician urgently in case of rapid palpitations or syncope. Alternatively, an additional risk stratification strategy may be utilized. Risk stratification of asymptomatic WPW pattern may be performed either invasively or by non-invasive means. Neither risk-stratification scheme is 100% perfect due to some false positives or false negatives. Non-invasive evaluation is usually a preferred initial modality. Patients can undergo exercise treadmill testing, ambulatory ECG monitoring, or sodium channel blocker challenge. The presence of an abrupt and clear loss of preexcitation at faster sinus rates on electrocardiogram suggests a weak or low-risk pathway. These pathways thus are unlikely to result in life-threatening ventricular rates during AF. They can usually be managed with watchful monitoring alone without subjecting them to an invasive EP study. On the other hand, if preexcitation persists at faster heart rates during exercise testing, or is persistent during the entire ambulatory monitoring period, then it may suggest that an invasive evaluation may be further needed. However, it does not necessarily mean that the pathway is "high-risk."

The 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS guidelines indicate that in asymptomatic patients with WPW pattern, EP study is reasonable, and ablation is reasonable for accessory pathways found to be either at high risk or in patients with high-risk occupations.[16] The measurement of the Shortest Pre-Excited R-R Interval (SPERRI) is used to determine accessory pathway properties on invasive study. A SPERRI of 220 to 250 ms and especially less than 220 ms is more commonly seen in patients with WPW who have experienced cardiac arrest. Thus, SPERRI less than 250 ms may be considered as an indication for consideration of ablation. All of these options should involve a careful discussion of the risks/benefits with the patient and their family.(A1)

Treatment of patients who have demonstrated WPW syndrome can be broken down into two categories. Patients presenting with an acute tachyarrhythmia and patients with known WPW pattern and prior symptomatic episodes but currently without an arrhythmia or symptoms. This second group of patients is similar to patients with known WPW pattern only as they do not require immediate treatment. They differ because they have proven that their accessory pathway is capable of initiating and maintaining or conducting an arrhythmia. This places them at a higher risk of recurrent arrhythmias, and they should be evaluated and treated. The treatment of choice for symptomatic patients is an accessory pathway catheter ablation. This is commonly done by radiofrequency current ablation, but cryoablation can also be utilized.[21][4] Catheter ablation has become the first-line treatment for symptomatic patients due to its high success rate and low-risk profile. The 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS guidelines utilize this as first-line therapy for symptomatic patients. Other treatment options include surgical ablation, which has a better success rate than catheter ablation and overall low mortality rate but is generally only attempted after failed catheter ablation due to the increased invasiveness of the procedure.[22] Medical therapy is available for patients who are not a candidate for catheter or surgical ablation or who do not wish to pursue these therapies. In patients without structural or ischemic heart disease, flecainide, and propafenone are deemed reasonable by the 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS guidelines, while dofetilide or sotalol are reasonable options in patients with structural heart disease. AV nodal blocking agents, including beta-blockers, verapamil, diltiazem, or digoxin, may be reasonable only in the setting or orthodromic AVRT or WPW pattern on ECG. Amiodarone may be considered should other medical therapies be ineffective or contraindicated in patients with AVRT or pre-excited AF.[16](A1)

A patient with known WPW pattern on baseline ECG or prior episode of WPW syndrome-related tachyarrhythmia who presents with an acute tachyarrhythmia will require acute medical management. The patient who presents with an acute tachyarrhythmia can be managed following the "2010 American Heart Association guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care" The first step in this algorithm is determining if the patient has a pulse. If no pulse is identified, CPR should be initiated, and the patient should be managed using the Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) Cardiac Arrest Algorithm. If a pulse is Identified, then management can proceed using the ACLS Tachycardia Algorithm.

According to the ACLS tachycardia algorithm, patients with persisting tachyarrhythmia who are deemed hemodynamically unstable as determined by identification of hypotension, acutely altered mental status, signs of shock, ischemic chest discomfort, or acute heart failure should undergo synchronized cardioversion or defibrillation. A trial of adenosine may be considered for a regular narrow complex tachycardia.[16][18][19](A1)

Pharmacological treatment of a hemodynamically stable acute tachyarrhythmia suspected to involve an accessory pathway must be based on the type of arrhythmia and accessory pathway present as certain pharmacological treatments may be detrimental or even fatal. Pathways that are not involved in the initiation and maintenance of an arrhythmia leading to AVRT will conduct an arrhythmia generated elsewhere in the heart. In the setting of an accessory pathway capable of rapid antegrade conduction, rapid atrial arrhythmias can be conducted to the ventricle inducing rapid ventricular rates that may deteriorate into ventricular fibrillation and cardiac arrest. AV nodal blockade can induce this scenario if given in the setting of a bystander accessory pathway and rapid atrial rhythm, as seen in atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, or other atrial tachycardias. These arrhythmias will be wide complex tachycardia and may be regular or irregular, depending on the underlying arrhythmia. Without electrophysiologic study, antidromic AVRT will be difficult to diagnose definitively and should, therefore, be managed similarly with avoidance of nodal blocking agents. The pharmacologic treatment of choice for antidromic AVRT is procainamide. In the setting of preexcitation and atrial fibrillation, AV nodal blockade is contraindicated. Procainamide and ibutilide are agents of choice in atrial fibrillation with preexcitation on ECG. Amiodarone has been used in WPW pattern with atrial fibrillation, but some evidence suggests that it is less effective and has a higher risk of precipitating ventricular fibrillation. If there remains any doubt about the diagnosis of a wide complex tachycardia, it is recommended that it be managed as suspected ventricular tachycardia.[16][18][19][23][24](A1)

Patients with WPW pattern on ECG who present with hemodynamically stability, orthodromic AVRT will demonstrate a regular narrow complex tachycardia. They can be managed similarly to other regular narrow complex supraventricular tachycardias. Vagal maneuvers followed by a trial of adenosine are the first-line therapy. The 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS guidelines recommend beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers as the second-line agents with electric cardioversion being reserved for refractory arrhythmias. If there is any doubt about the diagnosis of orthodromic AVRT or in the setting of aberrant conduction leading to a wide complex appearance, caution should be used with nodal blocking agents. Managing as an undifferentiated wide complex tachycardia may be prudent.[16][18][19](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for WPW pattern and syndrome is broad and can be broken down by the symptoms, ECG pattern, or with the type of dysrhythmia that the patient presents. Since the WPW pattern is defined by its ECG findings of a short PR interval, widened QRS complex with a slurred delta wave, the differential diagnosis can include any condition that can cause similar ECG findings. The differential diagnosis includes myocardial infarction, bundle branch block, congenital or acquired structural heart abnormalities, hypertrophy, premature junctional or ventricular complexes, ventricular bigeminy, accelerated idioventricular rhythms, electrical alternans, pacemaker, or metabolic/electrolyte abnormalities.[16][20][25][26][27]

For patients with a history of or symptoms concerning for an episode of a tachyarrhythmia who have WPW pattern on a resting ECG, the differential diagnosis includes other causes or manifestations of these arrhythmias. An accessory pathway that participates in initiating and maintaining an arrhythmia can cause a regular narrow complex tachycardia from orthodromic AVRT or a regular wide complex tachycardia from antidromic AVRT. The arrhythmia may be irregular if there is variable conduction, recurring episodes of initiation and termination of AVRT, or the accessory pathway is propagating an arrhythmia generated elsewhere. Therefore, the differential must include causes of both wide and narrow, regular, or irregular complex tachycardias. These categories are broken down into groups below.[16]

Regular narrow complex tachycardia: Sinus tachycardia, atrial tachycardia, atrial flutter (with regular AV block), AVNRT, AVRT, junctional tachycardia.

Irregular narrow complex tachycardia: Atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter (with variable AV block), multifocal atrial tachycardia, sinus tachycardia with ectopic complexes, and any cause of a regular narrow complex tachycardia with variable conduction or ectopic complexes.

Regular wide complex tachycardia: Ventricular tachycardia, accelerated idioventricular rhythm, paced rhythm, artifact, and any SVT associated with aberrant ventricular conduction or accessory pathway or metabolic/electrolyte abnormalities.

Irregular wide complex tachycardia: Torsades de pointes, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, any cause of an irregular narrow complex tachycardia associated with abnormally aberrant conduction, metabolic/electrolyte abnormalities, any regular wide complex tachycardia associated with variable conduction or frequent ectopic complexes.

Prognosis

WPW pattern is a rare condition, and most patients with preexcitation on ECG will never have symptoms, associated arrhythmias, or the most feared complication of sudden cardiac death. Two population studies put the rate of sudden cardiac death between 0.0002 to 0.0015 per patient-years for patients with WPW pattern. Some risk factors place a patient at higher risk for sudden cardiac death, including male gender, age less than 35 years, history of atrial fibrillation or AVRT, multiple accessory pathways, septal location of the accessory pathway, the ability for rapid anterograde conduction of the accessory pathway.[2][3][4] Despite the low prevalence of WPW pattern or the low incidence of serious complications, it remains a dangerous medical condition. The prognosis for patients with WPW pattern has improved significantly as antiarrhythmic medications, and ablation techniques were developed over the last 80 years. For patients who have WPW syndrome, high-risk factors, or strong preference, radiofrequency catheter ablation can be curative and has high success rates with low rates of complications.[14]

Complications

The feared complication of WPW syndrome is sudden cardiac death (SCD). Population studies suggest that SCD is most often a result of ventricular fibrillation leading to cardiac arrest or with atrial fibrillation or circus movement tachycardia. The mechanism for deterioration to ventricular fibrillation leading to SCD is an accessory pathway that is capable of rapid antegrade conduction that allows rapid transmission of atrial impulses to the ventricle. This can be exacerbated or initiated by the use of AV nodal blocking agents, and care should be taken to avoid these medications in the setting of WPW pattern on resting ECG with rapid atrial arrhythmias; atrial fibrillation and flutter are the most dangerous given their excessively rapid rates. Recurrent or prolonged tachyarrhythmias can predispose to heart failure. Hemodynamic instability during a tachyarrhythmia can initiate or exacerbate comorbid medical conditions. Patients that experience syncope with acute arrhythmia are at risk for traumatic injuries.[28][2][4]

Consultations

A shared decision-making conversation should be held with patients who have WPW pattern on their ECG but no history concerning for or documented arrhythmia. Cardiology or electrophysiology referral is reasonable to discuss electrophysiologic testing for risk stratification. Catheter ablation is the recommended first-line therapy for patients with preexcitation on ECG who have a history of involved arrhythmias. Electrophysiology consultation or referral should be obtained.[16]

Deterrence and Patient Education

The dysrhythmias causing electrical abnormalities associated with WPW syndrome are a result of a congenital abnormality forming an accessory pathway. There is nothing that can be done to prevent WPW pattern. After WPW syndrome has manifested with the presentation of a tachyarrhythmia, an electrophysiologic study can be performed to map and assess risks of the accessory pathway, and catheter radiofrequency ablation of the pathway can be curative. For patients that this is not an option or preference, antiarrhythmic medications can be a reasonable alternative option.[16]

Pearls and Other Issues

Patients with atrial fibrillation and rapid ventricular response are often treated with amiodarone or procainamide. Procainamide and cardioversion are accepted treatments for conversion of tachycardia associated with Wolff Parkinson White syndrome (WPW). In acute AF associated with WPW syndrome, the use of IV amiodarone may potentially lead to ventricular fibrillation in some reports and thus should be avoided.

AV node blockers should be avoided in atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter with Wolff Parkinson White syndrome (WPW). In particular, avoid adenosine, diltiazem, verapamil, and other calcium channel blockers and beta-blockers. They can exacerbate the syndrome by blocking the heart's normal electrical pathway and facilitating antegrade conduction via the accessory pathway.

An acutely presenting wide complex tachycardia should be assumed to be ventricular tachycardia if doubt remains about the etiology.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome is a rare but dangerous condition. A high index of clinical suspicion and close attention to concerning symptoms may be crucial in making a diagnosis. Once a diagnosis or sufficient concern is established, an interprofessional approach will be necessary for further evaluation and management. This approach, paired with education and shared decision making with patients and their families, will help guide treatment plans.

It is often difficult to develop and carry out well structured and rigorous studies in rare medical conditions. Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome is no exception, and most of the evidence is drawn from case series and population studies. The pathophysiologic basis is well understood, and surgical or catheter ablation has been shown to be successful and low risk. In high-risk patients, ablation is the most definitive treatment, but more future studies would help delineate medical management and ablation thresholds in some low-risk patients. [Levels 3 and 4]

Media

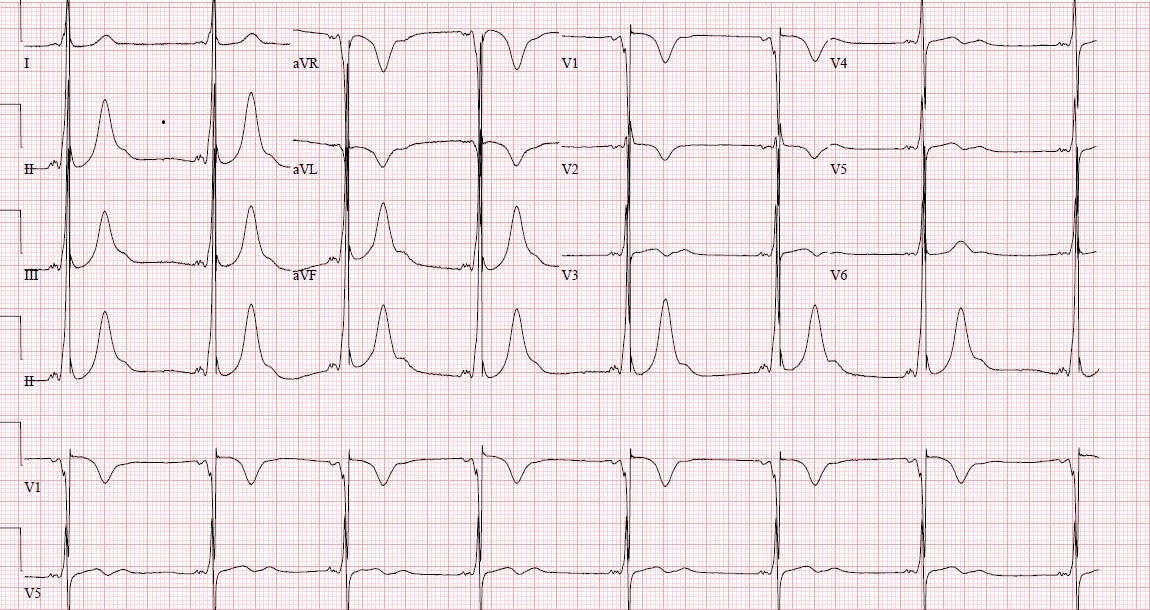

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome. A characteristic delta wave is seen in a patient with WPW. Note the short PR interval.

James Heilman, MD, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

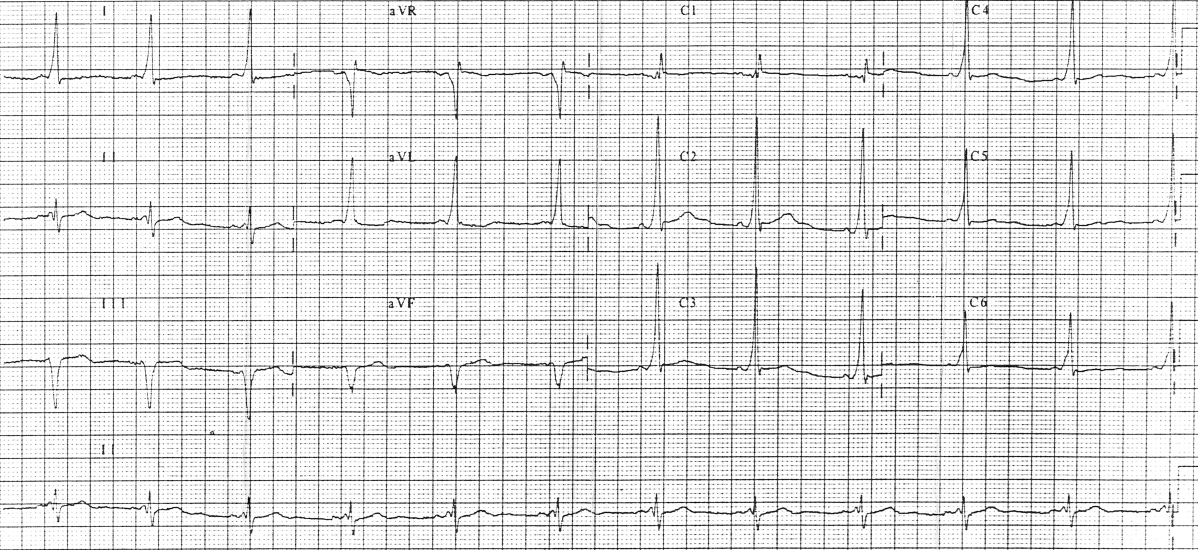

(Click Image to Enlarge)

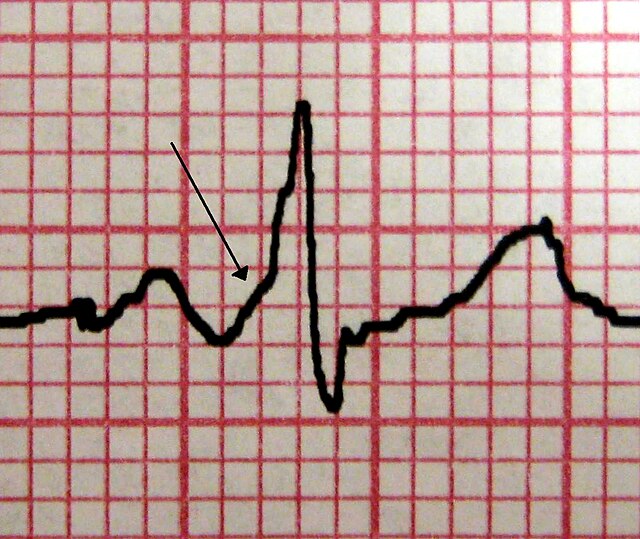

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Moorman A, Webb S, Brown NA, Lamers W, Anderson RH. Development of the heart: (1) formation of the cardiac chambers and arterial trunks. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2003 Jul:89(7):806-14 [PubMed PMID: 12807866]

Fitzsimmons PJ, McWhirter PD, Peterson DW, Kruyer WB. The natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in 228 military aviators: a long-term follow-up of 22 years. American heart journal. 2001 Sep:142(3):530-6 [PubMed PMID: 11526369]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMunger TM, Packer DL, Hammill SC, Feldman BJ, Bailey KR, Ballard DJ, Holmes DR Jr, Gersh BJ. A population study of the natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1953-1989. Circulation. 1993 Mar:87(3):866-73 [PubMed PMID: 8443907]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTimmermans C, Smeets JL, Rodriguez LM, Vrouchos G, van den Dool A, Wellens HJ. Aborted sudden death in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. The American journal of cardiology. 1995 Sep 1:76(7):492-4 [PubMed PMID: 7653450]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWolff L, Parkinson J, White PD. Bundle-branch block with short P-R interval in healthy young people prone to paroxysmal tachycardia. 1930. Annals of noninvasive electrocardiology : the official journal of the International Society for Holter and Noninvasive Electrocardiology, Inc. 2006 Oct:11(4):340-53 [PubMed PMID: 17040283]

Wilson FN. A case in which the vagus influenced the form of the ventricular complex of the electrocardiogram. 1915. Annals of noninvasive electrocardiology : the official journal of the International Society for Holter and Noninvasive Electrocardiology, Inc. 2002 Apr:7(2):153-73 [PubMed PMID: 12085794]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMirzoyev S, McLeod CJ, Asirvatham SJ. Embryology of the conduction system for the electrophysiologist. Indian pacing and electrophysiology journal. 2010 Aug 15:10(8):329-38 [PubMed PMID: 20811536]

Colavita PG, Packer DL, Pressley JC, Ellenbogen KA, O'Callaghan WG, Gilbert MR, German LD. Frequency, diagnosis and clinical characteristics of patients with multiple accessory atrioventricular pathways. The American journal of cardiology. 1987 Mar 1:59(6):601-6 [PubMed PMID: 3825901]

Zachariah JP, Walsh EP, Triedman JK, Berul CI, Cecchin F, Alexander ME, Bevilacqua LM. Multiple accessory pathways in the young: the impact of structural heart disease. American heart journal. 2013 Jan:165(1):87-92. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.10.025. Epub 2012 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 23237138]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKobza R, Toggweiler S, Dillier R, Abächerli R, Cuculi F, Frey F, Schmid JJ, Erne P. Prevalence of preexcitation in a young population of male Swiss conscripts. Pacing and clinical electrophysiology : PACE. 2011 Aug:34(8):949-53. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2011.03085.x. Epub 2011 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 21453334]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKrahn AD, Manfreda J, Tate RB, Mathewson FA, Cuddy TE. The natural history of electrocardiographic preexcitation in men. The Manitoba Follow-up Study. Annals of internal medicine. 1992 Mar 15:116(6):456-60 [PubMed PMID: 1739235]

Gollob MH, Green MS, Tang AS, Gollob T, Karibe A, Ali Hassan AS, Ahmad F, Lozado R, Shah G, Fananapazir L, Bachinski LL, Roberts R. Identification of a gene responsible for familial Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 2001 Jun 14:344(24):1823-31 [PubMed PMID: 11407343]

LEV M, GIBSON S, MILLER RA. Ebstein's disease with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome; report of a case with a histopathologic study of possible conduction pathways. American heart journal. 1955 May:49(5):724-41 [PubMed PMID: 14376326]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES), Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF), American Heart Association (AHA), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS), Cohen MI, Triedman JK, Cannon BC, Davis AM, Drago F, Janousek J, Klein GJ, Law IH, Morady FJ, Paul T, Perry JC, Sanatani S, Tanel RE. PACES/HRS expert consensus statement on the management of the asymptomatic young patient with a Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW, ventricular preexcitation) electrocardiographic pattern: developed in partnership between the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of PACES, HRS, the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF), the American Heart Association (AHA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS). Heart rhythm. 2012 Jun:9(6):1006-24. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.03.050. Epub 2012 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 22579340]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAl-Khatib SM, Arshad A, Balk EM, Das SR, Hsu JC, Joglar JA, Page RL. Risk Stratification for Arrhythmic Events in Patients With Asymptomatic Pre-Excitation: A Systematic Review for the 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Management of Adult Patients With Supraventricular Tachycardia: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016 Apr 5:67(13):1624-1638. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.018. Epub 2015 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 26409260]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePage RL, Joglar JA, Caldwell MA, Calkins H, Conti JB, Deal BJ, Estes NA 3rd, Field ME, Goldberger ZD, Hammill SC, Indik JH, Lindsay BD, Olshansky B, Russo AM, Shen WK, Tracy CM, Al-Khatib SM, Evidence Review Committee Chair‡. 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Management of Adult Patients With Supraventricular Tachycardia: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2016 Apr 5:133(14):e506-74. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000311. Epub 2015 Sep 23 [PubMed PMID: 26399663]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBhatia A, Sra J, Akhtar M. Preexcitation Syndromes. Current problems in cardiology. 2016 Mar:41(3):99-137. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2015.11.002. Epub 2015 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 26897561]

Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, Kronick SL, Shuster M, Callaway CW, Kudenchuk PJ, Ornato JP, McNally B, Silvers SM, Passman RS, White RD, Hess EP, Tang W, Davis D, Sinz E, Morrison LJ. Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010 Nov 2:122(18 Suppl 3):S729-67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970988. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20956224]

European Heart Rhythm Association, Heart Rhythm Society, Zipes DP, Camm AJ, Borggrefe M, Buxton AE, Chaitman B, Fromer M, Gregoratos G, Klein G, Moss AJ, Myerburg RJ, Priori SG, Quinones MA, Roden DM, Silka MJ, Tracy C, Smith SC Jr, Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Antman EM, Anderson JL, Hunt SA, Halperin JL, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B, Priori SG, Blanc JJ, Budaj A, Camm AJ, Dean V, Deckers JW, Despres C, Dickstein K, Lekakis J, McGregor K, Metra M, Morais J, Osterspey A, Tamargo JL, Zamorano JL, American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association Task Force, European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death). Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006 Sep 5:48(5):e247-346 [PubMed PMID: 16949478]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWang K, Asinger R, Hodges M. Electrocardiograms of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome simulating other conditions. American heart journal. 1996 Jul:132(1 Pt 1):152-5 [PubMed PMID: 8701858]

Rodriguez LM, Geller JC, Tse HF, Timmermans C, Reek S, Lee KL, Ayers GM, Lau CP, Klein HU, Crijns HJ. Acute results of transvenous cryoablation of supraventricular tachycardia (atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, atrioventricular nodal reentry tachycardia). Journal of cardiovascular electrophysiology. 2002 Nov:13(11):1082-9 [PubMed PMID: 12475096]

Holman WL, Kay GN, Plumb VJ, Epstein AE. Operative results after unsuccessful radiofrequency ablation for Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. The American journal of cardiology. 1992 Dec 1:70(18):1490-1 [PubMed PMID: 1442625]

Hirschl MM, Wollmann C, Globits S. A 2-year survey of treatment of acute atrial fibrillation in an ED. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2011 Jun:29(5):534-40. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.12.016. Epub 2010 May 1 [PubMed PMID: 20825828]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSobel RM, Dhruva NN. Termination of acute wide QRS complex atrial fibrillation with ibutilide. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2000 Jul:18(4):462-4 [PubMed PMID: 10919540]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGüler N, Eryonucu B, Bilge M, Erkoç R, Türkoğlu C. Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome mimicking acute anterior myocardial infarction in a young male patient--a case report. Angiology. 2001 Apr:52(4):293-5 [PubMed PMID: 11330514]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSammon M, Dawood A, Beaudoin S, Harrigan RA. An Unusual Case of Alternating Ventricular Morphology on the 12-Lead Electrocardiogram. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2017 Mar:52(3):348-353. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.08.027. Epub 2016 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 27727036]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSternick EB, Oliva A, Magalhães LP, Gerken LM, Hong K, Santana O, Brugada P, Brugada J, Brugada R. Familial pseudo-Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Journal of cardiovascular electrophysiology. 2006 Jul:17(7):724-32 [PubMed PMID: 16836667]

MacRae CA, Ghaisas N, Kass S, Donnelly S, Basson CT, Watkins HC, Anan R, Thierfelder LH, McGarry K, Rowland E. Familial Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome maps to a locus on chromosome 7q3. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1995 Sep:96(3):1216-20 [PubMed PMID: 7657794]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence