Introduction

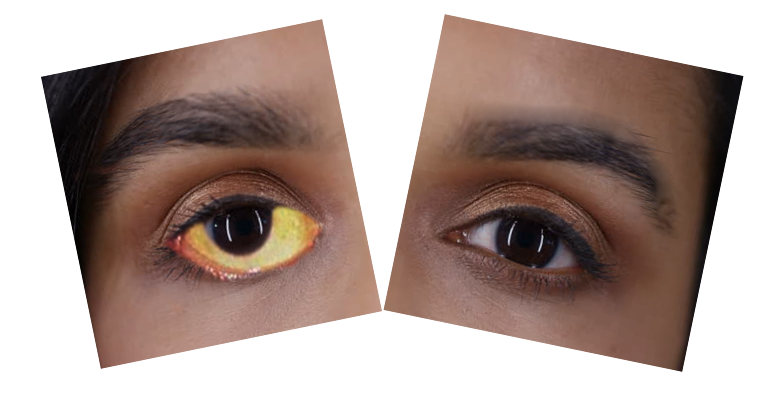

Jaundice, also known as hyperbilirubinemia,[1] is a yellow discoloration of the body tissue resulting from the accumulation of an excess of bilirubin. Deposition of bilirubin happens only when there is an excess of bilirubin, a sign of increased production or impaired excretion. The normal serum levels of bilirubin are less than 1mg/dl; however, the clinical presentation of jaundice as scleral icterus (peripheral yellowing of the eye sclera), is best appreciated only when the levels reach more than 3 mg/dl. Sclerae have a high affinity for bilirubin due to their high elastin content.[2] With further increase in serum bilirubin levels, the skin will progressively discolor ranging from lemon yellow to apple green, especially if the process is long-standing; the green color is due to biliverdin.[3]

Bilirubin has two components: unconjugated(indirect) and conjugated(direct), and hence elevation of any of these can result in jaundice. Icterus acts as an essential clinical indicator for liver disease, apart from various other insults.[4]

Yellowing of skin sparing the sclerae is indicative of carotenoderma which occurs in healthy individuals who consume excessive carotene-rich foods.[5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

CONJUGATED HYPERBILIRUBINEMIA[6]

Defect of canalicular organic anion transport [7]

- Dubin-Johnson syndrome

Defect of sinusoidal reuptake of conjugated bilirubin

- Rotor syndrome

Decreased intrahepatic excretion of bilirubin[8]

- Hepatocellular disease - Viral hepatitis A, B, D; alcoholic hepatitis; cirrhosis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, EBV, CMV, HSV, Wilson, autoimmune

- Cholestatic liver disease-Primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Infiltrative diseases (e.g., amyloidosis, lymphoma, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis)

- Sepsis and hypoperfusion states

- Total parenteral nutrition

- Drugs & Toxins - oral contraceptives, rifampin, probenecid, steroids, chlorpromazine, herbal medications (e.g., Jamaican bush tea, kava kava), arsenic

- Hepatic crisis in sickle cell disease

- Pregnancy

Extrahepatic cholestasis (biliary obstruction)[9]

- Choledocholithiasis

- Tumors (e.g., cholangiocarcinoma, head of pancreas cancer)

- Extrahepatic biliary atresia

- Acute and chronic pancreatitis

- Strictures

- Parasitic infections (e.g., Ascaris lumbricoides, liver flukes)

UNCONJUGATED HYPERBILIRUBINEMIA

Excess production of bilirubin

- Hemolytic anemias, extravasation of blood in tissues, dyserythropoiesis

Reduced hepatic uptake of bilirubin

- Gilbert syndrome [10]

Impaired conjugation[11]

- Crigler–Najjar syndrome type 1 and 2

- Hyperthyroid

- Estrogen

Epidemiology

The prevalence of jaundice differs among patient populations; newborns and elderly more commonly present with the disease.[12]

The causes of jaundice also vary with age, as mentioned above. Around 20 percent of term babies are found with jaundice in the first week of life, primarily due to immature hepatic conjugation process.[13] Congenital disorders, overproduction from hemolysis, defective bilirubin uptake, and defects in conjugation are also responsible for jaundice in infancy or childhood. Hepatitis A was found to be the most afflicting cause of jaundice among children.[14][15] Bile duct stones, drug-induced liver disease, and malignant biliary obstruction occur in the elderly population.

Men have an increased prevalence of alcoholic and non-alcoholic cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis B, malignancy of pancreas, or sclerosing cholangitis.[16] In contrast, women demonstrate higher rates of gallbladder stones, primary biliary cirrhosis, and gallbladder cancer.[17]

Kernicterus or Bilirubin-induced neurologic dysfunction (BIND), a complication of severe jaundice is a very rare cause of death in neonates with a death rate of 0.28 deaths per one million live births.[18]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of jaundice is best explained by dividing the metabolism of bilirubin into three phases: prehepatic, hepatic, and post-hepatic.[19][4]

PREHEPATIC

- Production - Bilirubin is the end product of heme, which is released by senescent or defective RBCs. In the reticuloendothelial cells of spleen, liver and bone marrow, heme released from the RBC undergoes a series of reactions to form the final product bilirubin:

Heme-->Biliverdin-->Bilirubin (insoluble due to tight hydrogen bonding)

HEPATIC

- Hepatocellular uptake - The bilirubin released from the reticuloendothelial system is in an unconjugated form (i.e., non-soluble) and gets transported to the hepatocytes bound to albumin which accomplishes solubility in blood. The albumin-bilirubin bond is broken, and the bilirubin alone is then taken into the hepatocytes through a carrier-membrane transport and bound to proteins in the cytosol to decrease the efflux of bilirubin back into the plasma.

- Conjugation of bilirubin - This unconjugated bilirubin then proceeds to the endoplasmic reticulum, where it undergoes conjugation to glucuronic acid resulting in the formation of conjugated bilirubin, which is soluble in the bile. This is rendered by the action of UDP-glucuronosyl transferase.

POSTHEPATIC

- Bile secretion from hepatocytes- Conjugated bilirubin is now released into the bile canaliculi into the bile ducts, stored in the gallbladder, reaching the small bowel through the ampulla of Vater and finally enters the colon.

- Intestinal metabolism and Renal transport- The intestinal mucosa does not reabsorb conjugated bilirubin due to its hydrophilicity and large molecular size. The colonic bacteria deconjugate and metabolize bilirubin into urobilinogen’s, 80% of which gets excreted into the feces and stercobilin and the remaining (10 to 20%) undergoes enterohepatic circulation. Some of these urobilin’s are excreted through the kidneys imparting the yellow pigment of urine.

Dysfunction in prehepatic phase results in elevated serum levels of unconjugated bilirubin while insult in post hepatic phase marks elevated conjugated bilirubin. Hepatic phase impairment can elevate both unconjugated and conjugated bilirubin.

Increased urinary excretion of urobilinogen can be due to increased production of bilirubin, increased reabsorption of urobilinogen from the colon, or decreased hepatic clearance of urobilinogen.

Histopathology

There are four different patterns of intrahepatic cholestasis, namely[20]:

- Cytoplasmic cholestasis: fine yellow pigment (bile) filling the cytoplasm of hepatic cells.

- Canalicular cholestasis: Bile found in the canaliculi.

- Ductular cholestasis: Accumulation of bile in the periportal bile ductules of Hering. Ductular cholestasis is associated with severe obstruction and sepsis.

- Ductal cholestasis: Demonstrates the presence of bile casts in portal bile ducts.

The histopathological changes of excess bile appear to result from the detergent effect of retained bile acids.

Toxicokinetics

As mentioned earlier, the serum level of bilirubin is a balance between production and hepatic excretion. After reaching the colon, the bacteria metabolize it into urobilinogen. A vast majority of urobilinogen is converted in stercobilin and excreted in feces. About 10 to 20% of urobilin gets reabsorbed by the action of beta-glucuronidase in the brush border of the gut and facilitates enterohepatic circulation and re-excreted by the liver; less than 3mg/dl escapes the hepatic uptakes and filters into the urine.[4]

Owing to its lipid soluble nature, bilirubin may cross the blood-brain barrier and thus enter the brain. Its clearance from the brain is ensured by the presence of an enzyme on the inner mitochondrial membrane, which aids in the oxidation of bilirubin, thus protecting against its neurotoxic effects. The mechanism of toxicity is yet obscure, but bilirubin has a higher affinity to settle in glia and neurons.

However, in newborns, since the blood-brain barrier is yet to develop, pathological increase in serum levels of bilirubin can result in death in the neonatal period or survival with disastrous neurological sequalae called kernicterus. Also, newborns are at increased risk due to lack of colonic bacteria resulting in deconjugation and enterohepatic reabsorption by b-glucuronidase enzymes resulting in hyperbilirubinemia.[21]

History and Physical

History

Patients usually present with varying symptoms apart from yellowish discoloration of skin along with pruritus, thus providing clues to narrow down the etiology or can also be asymptomatic. A thorough questioning regarding the use of drugs, alcohol or other toxic substances, risk factors for hepatitis (travel, unsafe sexual practices), HIV status, personal or family history of any inherited disorders or hemolytic disorders is vital. Other important points include the duration of jaundice; and the presence of any coexisting signs and symptoms, like a joint ache, rash, myalgia, changes in urine and stool.[22] A history of arthralgias and myalgias before yellowing indicates hepatitis, either due to drugs or viral infections.

Further, fever, chills, severe right-upper-quadrant-abdominal pain as seen in cholangitis and anorexia, malaise as seen in hepatitis and significant weight loss suggesting malignancy obstructing the bile ducts provide additional information for diagnosis. Additionally, a patient with a history of ulcerative colitis may present with hyperbilirubinemia due to PSC.

Physical

Physical examination begins by evaluation of body habitus and nutritional status. Temporal and proximal muscle wasting suggests malignancy or cirrhosis.[23] It is worth reviewing the well-known stigmata of chronic liver disease, which includes spider nevi, palmar erythema, gynecomastia, caput medusae, Dupuytren contractures, parotid gland enlargement, and testicular atrophy. Palpable lymph nodes can also direct the clinician towards malignancy (left supraclavicular & periumbilical). Increased volume status of the patient evidenced by jugular venous distension can be a sign of right-sided heart failure, suggesting hepatic congestion.

The abdominal examination should provide information on the presence of hepatosplenomegaly, or ascites. Jaundice with ascites indicates either cirrhosis or malignancy with peritoneal spread.

Right upper quadrant tenderness with palpable gallbladder (Courvoisier sign) suggests obstruction of the cystic duct due to malignancy.[24]

Evaluation

(After obtaining a thorough history and performing physicals, the most important laboratory test to be done is liver function tests.[25][26]

Liver function tests - to check serum levels of aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma-glutamyltransferase, serum albumin, protein, and bilirubin

AST, ALT and ALP levels - if the liver transaminase levels increase but ALP levels are low, then the insult is hepatic in origin.

- AST/ALT ratio is more than 2 to 1 in alcoholic liver disease.

- AST and ALT values are in 1000s; then the hepatocellular disease is likely due to toxins like acetaminophen or ischemia or viral.

- If ALP levels are five times elevated than normal and liver transaminases are normal or less than two times normal, then the most likely cause is biliary obstruction. The high serum ALP levels due to a biliary injury can be differentiated from bone disorders by ordering a GGT serum profile, increased levels confirm hepatic origin.

- If AST, ALT and ALP levels are normal- then the jaundice is not due to liver or bile duct injury. The cause must probably be pre-hepatic: inherited disorders of liver conjugation or blood disorders or defect in hepatic excretion (Rotor, Dubin-Johnson).

Serum Bilirubin - whether there is a rise in unconjugated or conjugated bilirubin

In addition to the liver panel, all jaundiced patients should have additional tests such as albumin and prothrombin time – which are indicative of chronic and acute liver function, respectively. The inability of prothrombin time to correct with parenteral administration of vitamin K suggests severe hepatocellular dysfunction.

The results of the bilirubin, enzymes, and liver function tests will direct the diagnosis towards a hepatocellular or cholestatic cause and offer some idea of the duration and severity of the disease.

Further evaluation can be conducted based on the initial assessment.

Hepatocellular workup: viral serologies, autoimmune antibodies, serum ceruloplasmin, ferritin.

Cholestatic workup: Additional tests include abdominal ultrasound, CT, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS).

Treatment / Management

Treatment of choice for jaundice is the correction of the underlying hepatobiliary or hematological disease, when possible.

Pruritis associated with cholestasis can be managed based on the severity. For mild pruritis, warm baths or oatmeal baths can be relieving. Antihistamines can also help with pruritis.[27] Patients with moderate to severe pruritis respond to bile acid sequestrants such as cholestyramine or colestipol. Other less effective therapies include rifampin, naltrexone, sertraline, or phenobarbital. If medical treatments fail, liver transplantation may be the only effective therapy for pruritis.[28](B3)

Jaundice is an indication for hepatic decompensation and may be an indication for liver transplant evaluation depending on the severity of the hepatic injury.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential for yellowish discoloration of the skin is narrow. Healthy individuals with high consumption of vegetables and fruits that contain carotene, such as carrots can present with carotenoderma which classically spares the sclerae.[5]

Quinacrine leads to yellowish discoloration of the skin in up to one-third of patients treated with it.[29]

Prognosis

Prognosis of jaundice depends on the etiology.

Etiologies of jaundice with excellent prognosis include jaundice from resorption of hematomas, physiologic jaundice of newborn, breastfeeding, breast milk jaundice, Gilbert syndrome, choledocholithiasis.

As a general rule, malignant biliary obstructions and cirrhosis with jaundice predict a poorer prognosis.[30]

Complications

Indirect (insoluble) bilirubin is harmful to cells and cellular structures. Due to the physiologic mechanisms that protect against elevated bilirubin, the toxic effects are limited to neonates due to the poorly developed blood-brain barrier. High levels of bilirubin are neurotoxic and can lead to permanent neurologic injury (kernicterus) (Bilirubin-induced neurologic dysfunction).[21]

Consultations

Specific challenging patients may require specialty consultations for further workup and management. Gastroenterology specialists most frequently consult on undiagnosed cases of jaundice.[31]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Most cases of jaundice can be effectively prevented by following a few simple recommendations which include:[32]

- Avoid herbal medications without consulting with a physician, most herbal supplements are toxic to the liver and can cause irreversible liver damage leading to jaundice

- Avoid smoking, consumption of alcohol, and intravenous drugs

- Avoid exceeding the recommended dose on prescribed medications

- Visit your doctor if you notice yellowish discoloration of body tissue

- Encourage safe sex practices

- Always get the recommended vaccines before traveling to a foreign country

Pearls and Other Issues

The best initial step in the evaluation of jaundice is history and physical examination. The next step is to classify jaundice by etiology and type-Hepatocellular, cholestatic or mixed.

The basic mechanisms of jaundice include elevated production, decreased uptake, and faulty conjugation.

Treatment focuses on the cause.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The biggest challenges in improving patient health outcome include a healthcare delivery system that focuses more on treating as opposed to preventing disease. Most cases of jaundice are preventable by vaccinations, safe sex practices, health education, risk factor modification.

The responsibility of the healthcare team in the incidence and management of jaundice is well known. Physicians, nurses, and pharmacists working together can significantly improve team outcomes. Encouragement from health care professionals to promote breastfeeding is vital in the management of neonatal jaundice.

With the wide range of etiologies for jaundice, the entire interprofessional team must collaborate to ensure optimal patient outcomes. Clinicians, including NPs and PAs, will be involved in the diagnosis and selection of therapy based on etiology. Nursing will work on patient compliance, and depending on the etiology, counseling the patient on lifestyle and other changes, and inform the treating clinicians about potential risks, non-compliance, and adverse reactions to therapy. Pharmacists are responsible for reporting back to the rest of the team on medication interactions following a medication review, and verifying dosing and duration; any concerns need to be brought to the attention of nursing and/or the prescriber. Only through this type of interprofessional collaboration can the healthcare team ensure the treatment matches the diagnosis and is executed in the best possible manner to bring about successful outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Schwarzenbach HR. [Jaundice and pathological liver values]. Praxis. 2013 Jun 5:102(12):727-9. doi: 10.1024/1661-8157/a001333. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23735764]

Leung TS, Outlaw F, MacDonald LW, Meek J. Jaundice Eye Color Index (JECI): quantifying the yellowness of the sclera in jaundiced neonates with digital photography. Biomedical optics express. 2019 Mar 1:10(3):1250-1256. doi: 10.1364/BOE.10.001250. Epub 2019 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 30891343]

Roche SP, Kobos R. Jaundice in the adult patient. American family physician. 2004 Jan 15:69(2):299-304 [PubMed PMID: 14765767]

Vítek L, Ostrow JD. Bilirubin chemistry and metabolism; harmful and protective aspects. Current pharmaceutical design. 2009:15(25):2869-83 [PubMed PMID: 19754364]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAl Nasser Y, Jamal Z, Albugeaey M. Carotenemia. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521299]

Modha K. Clinical Approach to Patients With Obstructive Jaundice. Techniques in vascular and interventional radiology. 2015 Dec:18(4):197-200. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2015.07.002. Epub 2015 Jul 16 [PubMed PMID: 26615159]

Strassburg CP. Hyperbilirubinemia syndromes (Gilbert-Meulengracht, Crigler-Najjar, Dubin-Johnson, and Rotor syndrome). Best practice & research. Clinical gastroenterology. 2010 Oct:24(5):555-71. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.07.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20955959]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNguyen KD, Sundaram V, Ayoub WS. Atypical causes of cholestasis. World journal of gastroenterology. 2014 Jul 28:20(28):9418-26. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9418. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25071336]

Hucl T. [Malignant biliary obstruction]. Casopis lekaru ceskych. 2016:155(1):30-7 [PubMed PMID: 26898789]

Fretzayas A, Moustaki M, Liapi O, Karpathios T. Gilbert syndrome. European journal of pediatrics. 2012 Jan:171(1):11-5. doi: 10.1007/s00431-011-1641-0. Epub 2011 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 22160004]

Memon N, Weinberger BI, Hegyi T, Aleksunes LM. Inherited disorders of bilirubin clearance. Pediatric research. 2016 Mar:79(3):378-86. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.247. Epub 2015 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 26595536]

Muchowski KE. Evaluation and treatment of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. American family physician. 2014 Jun 1:89(11):873-8 [PubMed PMID: 25077393]

Maisels MJ, Gifford K, Antle CE, Leib GR. Jaundice in the healthy newborn infant: a new approach to an old problem. Pediatrics. 1988 Apr:81(4):505-11 [PubMed PMID: 3353184]

Aggarwal R, Goel A. Hepatitis A: epidemiology in resource-poor countries. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2015 Oct:28(5):488-96. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000188. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26203853]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLinder KA, Malani PN. Hepatitis A. JAMA. 2017 Dec 19:318(23):2393. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.17244. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29094153]

Ilic M, Ilic I. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer. World journal of gastroenterology. 2016 Nov 28:22(44):9694-9705 [PubMed PMID: 27956793]

Purohit T, Cappell MS. Primary biliary cirrhosis: Pathophysiology, clinical presentation and therapy. World journal of hepatology. 2015 May 8:7(7):926-41. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i7.926. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25954476]

Bousema S, Govaert P, Dudink J, Steegers EA, Reiss IK, de Jonge RC. [Kernicterus is preventable but still occurs]. Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde. 2015:159():A8518 [PubMed PMID: 25944067]

HSIA DY. BILIRUBIN METABOLISM. Pediatric clinics of North America. 1965 Aug:12():713-22 [PubMed PMID: 14312834]

Feuer G, Di Fonzo CJ. Intrahepatic cholestasis: a review of biochemical-pathological mechanisms. Drug metabolism and drug interactions. 1992:10(1-2):1-161 [PubMed PMID: 1511611]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLe Pichon JB, Riordan SM, Watchko J, Shapiro SM. The Neurological Sequelae of Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia: Definitions, Diagnosis and Treatment of the Kernicterus Spectrum Disorders (KSDs). Current pediatric reviews. 2017:13(3):199-209. doi: 10.2174/1573396313666170815100214. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28814249]

Trépo C, Chan HL, Lok A. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet (London, England). 2014 Dec 6:384(9959):2053-63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60220-8. Epub 2014 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 24954675]

Nishikawa H, Osaki Y. Liver Cirrhosis: Evaluation, Nutritional Status, and Prognosis. Mediators of inflammation. 2015:2015():872152. doi: 10.1155/2015/872152. Epub 2015 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 26494949]

. Ludwig Courvoisier (1843-1918). Courvoisier's sign. JAMA. 1968 May 13:204(7):627 [PubMed PMID: 4869570]

Blann A. What is the purpose of liver function tests? Nursing times. 2014 Feb 5-11:110(6):17-9 [PubMed PMID: 24669469]

Jalan R, Hayes PC. Review article: quantitative tests of liver function. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 1995 Jun:9(3):263-70 [PubMed PMID: 7654888]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBassari R, Koea JB. Jaundice associated pruritis: a review of pathophysiology and treatment. World journal of gastroenterology. 2015 Feb 7:21(5):1404-13. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i5.1404. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25663760]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTrotter JF. Liver transplantation around the world. Current opinion in organ transplantation. 2017 Apr:22(2):123-127. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000392. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28151809]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNamas R, Marquardt A. Case Report and Literature Review: Quinacrine-induced Cholestatic Hepatitis in Undifferentiated Connective Tissue Disease. The Journal of rheumatology. 2015 Jul:42(7):1354-5. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150050. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26136554]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShin SJ, Park H, Sung YN, Yoo C, Hwang DW, Park JH, Kim KP, Lee SS, Ryoo BY, Seo DW, Kim SC, Hong SM. Prognosis of Pancreatic Cancer Patients with Synchronous or Metachronous Malignancies from Other Organs Is Better than Those with Pancreatic Cancer Only. Cancer research and treatment. 2018 Oct:50(4):1175-1185. doi: 10.4143/crt.2017.494. Epub 2017 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 29268568]

Biggerstaff ME, Short N. Evaluation of specialist referrals at a rural health care clinic. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners. 2017 Jul:29(7):410-414. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12480. Epub 2017 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 28695714]

Papatheodoridis G, Thomas HC, Golna C, Bernardi M, Carballo M, Cornberg M, Dalekos G, Degertekin B, Dourakis S, Flisiak R, Goldberg D, Gore C, Goulis I, Hadziyannis S, Kalamitsis G, Kanavos P, Kautz A, Koskinas I, Leite BR, Malliori M, Manolakopoulos S, Matičič M, Papaevangelou V, Pirona A, Prati D, Raptopoulou-Gigi M, Reic T, Robaeys G, Schatz E, Souliotis K, Tountas Y, Wiktor S, Wilson D, Yfantopoulos J, Hatzakis A. Addressing barriers to the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of hepatitis B and C in the face of persisting fiscal constraints in Europe: report from a high level conference. Journal of viral hepatitis. 2016 Feb:23 Suppl 1():1-12. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12493. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26809941]