Introduction

Lenticonus is an ocular morphological pathology in which there is abnormal conical protrusion and bulge of the lens capsule due to thinning of the lens capsule.[1] The protrusion on the anterior lens capsule is called anterior lenticonus, and the protrusion on the posterior capsule is called posterior lenticonus. Both anterior and posterior lenticonus can also coexist in the general patient population. The diameter of the conical protrusion is usually between 2 to 7 mm.[2] Alport syndrome was initially described in 1972 as acute hemorrhagic nephritis with deafness. It is a rare genetic disorder characterized by glomerulonephritis, hearing loss, and sensorineural hearing loss.[3]

Anterior lenticonus is associated with Alport syndrome, and posterior lenticonus occurs in Lowe syndrome, although most reports suggest it is not linked to any systemic disease.[4] The most common differential of lenticonus is lentiglobus, where the lens has a global spherical protuberance.[4]

Lenticonus patients present with myopia and astigmatism. The other common findings in Alport syndrome are arcus juvenilis, cataract, posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy, and dot and flecked retinopathy. There management options for a lenticonus can be spectacles, contact lenses, lens aspiration, IOL implantation along with anterior vitrectomy.[5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Epidemiology

Alport syndrome is commonly present at a young age, from 5 to 20 years of age. These children present with chronic haematuria before the fourth decade, depending on the collagen mutation. Sensorineural hearing loss manifests in adulthood. X-linked Alport syndrome affects more men than women.[7] Autosomal dominant and recessive have an equal frequency in men and women, and the severity is also similar.[8]

Anterior lenticonus usually presents bilaterally in patients with Alport syndrome, a hereditary systemic pathology with a prevalence of 1/5000 in the normal population. Out of all patients, approximately 85% are X-linked, 10% have autosomal recessive inheritance, and autosomal dominant 5%.[9]

Progressive renal failure, sensorineural hearing loss, and ocular manifestations develop in approximately 11 to 43% of the patients. Flecked retinopathy and anterior lenticonus are seen in approximately 25% of the patients with X-linked Alport. PPCD is seen in very few patients.[10]

Pathophysiology

Anterior Lenticonus

Type 4 collagen is commonly found in the glomerular basement membrane of the glomerulus, lenticular capsule, stria vascularis of the cochlea, internal limiting membrane, Bruch's membrane of the retina, Bowman's and Descemet membrane of the cornea.[11] Usually, the alpha three, four, and five collagen chains are missing from the afflicted basement membrane because the presence of abnormal collagen will interfere with all three collagen chain stability. This collagen loss from the basement membrane will result in altered ultrastructural characteristics of the basement membrane. The altered basement membrane in Alport syndrome has a defective α1α1α2 network.[12]

This weakened membrane has structural stability and is more prone to biomechanical strain. The basement membrane of the kidney is also affected in Alport, which results in improper blood filtration, leading to haematuria and proteinuria. They cause progressive kidney damage and result in kidney failure. Collagen type 4 is an essential constituent of inner ear structure, and patients with Alport syndrome develop sensorineural hearing loss due to damage to the Organ of Corti. This causes abnormal transmission of sound waves and defective conversion to electric signals in the brain.[7]

Defective collagen in the cornea can cause changes in the Bowmans and Descemet's, whose primary function is to combine three main corneal layers: epithelium, stroma, and endothelium.[13] This causes reduced tension and low adhesion to the epithelium, which is explained by recurrent corneal erosions and posterior polymorphous dystrophy. The vesicles present in posterior corneal dystrophy result from the degeneration of vacuoles of the dead cells or multi-layered cell extension from the Descemet membrane.[14]

The capsule of the lens also has the same problem as the cornea and results in partial tears that may rupture. This can also manifest as a conical protrusion in the thinnest part of the lens capsule. The lens can be tight as well as elastic, as per various reports.[15] In cases with elastic capsules, spontaneous rupture can be seen. Cataracts can also occur. The lenticonus progression stop after cataract development. Posterior lenticonus can also occur, but it is less common. The retinal injuries are located in the inner retinal layers and act as a barrier in the natural retinal microenvironment, cellular nutrition, debris, and watertight compartment.[5]

Posterior Lenticonus

The pathogenesis of the posterior lenticonus is still an area of active research. The main proposed mechanisms are the tractional effect on the posterior lens capsule by the remnants of the hyaloid artery system as well as a disturbance in the tunica vasculosa lentis has been suggested.[16]

The other proposed mechanism includes the presence of vitritis and overgrowth of posterior lenticular fibers, which produce a phakoma of the lens. But none of the theories is proven yet. As per the previous hypothesis, it can also be a congenital weakness of the posterior lens capsule, which is genetically determined. The other proposed mechanism is secondary to trauma and aberrant hyperplasia of the subcapsular epithelium overlying the cone. As per Franceschetti and Rickii, posterior lenticonus is due to aberrant hypertrophy of the posterior lens cortex.[16]

Histopathology

Histopathological sections from the lenticonus show a thin central anterior lenticular capsule with normal epithelium. Anterior capsular electron microscopy reveals multiple longitudinal and irregular zones of capsular dehiscence. A few areas of fibrillar and electron-dense material are also seen. In Alport syndrome, irregular adjacent cells are also seen. There is also a reduction in the number of lens epithelial cells, which can be atypically arranged, and partial capsular dehiscence is present with fibrillar material and vacuoles.[17]

History and Physical

Alport Syndrome

In Alport syndrome, basement membrane dysfunction is characterized by ocular abnormalities, sensorineural hearing loss, and progressive hereditary nephritis. In 85% of cases, the inheritance is X-linked, autosomal recessive in 10%, and autosomal dominant in 5%.[18]

Alport has a genetic defect in the basement membrane collagen. A. Cecil Alport first described them in 1927. Homozygous males are severely affected, and females have a milder form of Alport, where symptoms are microscopic haematuria and normal renal function. Alport genetic disruption of the glomerular basement membrane is secondary to mutations in the gene COL 4A 3,4, 5. The genes code for collagen type 4 alpha 3-5 chains.[19]

These patients can present with pain, haematuria, proteinuria, renal failure (edema and hypertension), sensorineural hearing loss, anterior lenticonus and dot, fleck retinopathy, and posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy. The other additional ocular abnormalities are posterior lenticonus, cataract, and retinal detachment.[4]

Ocular Symptoms

The patients with Alport syndrome present with pain, watering, diminished vision, and photophobia secondary to corneal erosions. Progressive vision loss can occur secondary to posterior polymorphous dystrophy.[10] Lenticular myopia manifests due to anterior lenticonus. Astigmatism due to lenticular changes and reduced visual acuity caused due to cataracts. Visual acuity loss can also occur due to the macular hole, dot, and fleck retinopathy. Macular holes respond poorly to surgery.[20]

Slit Lamp Ocular Signs

More Common

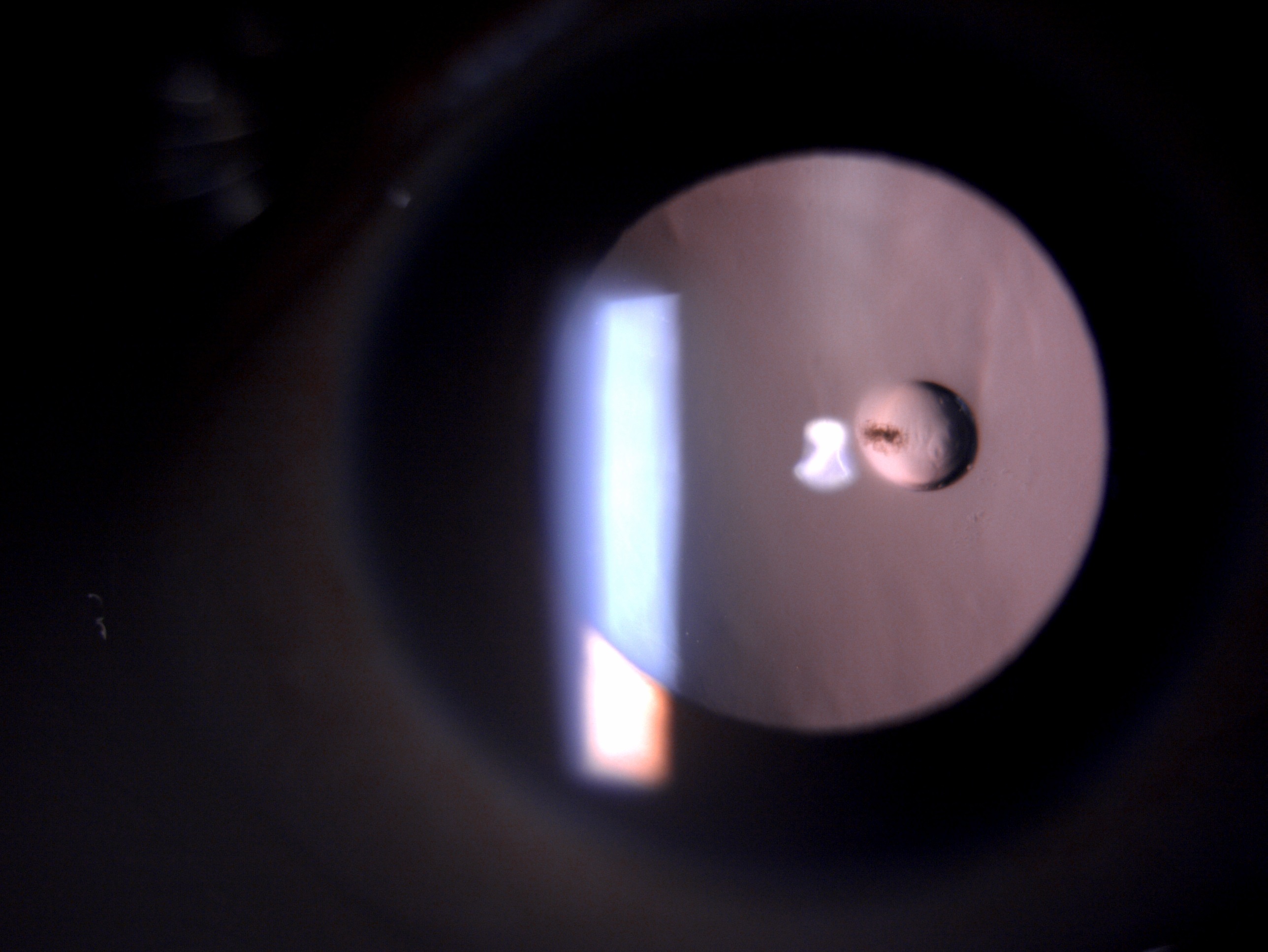

Careful oblique and retroillumination reveal an oil droplet reflex which is usually axial in a location with dimensions of 2-7 mm. Lenticonus configuration on slit lamp is described as transparent, sharply demarcated localized conical projection of the lenticular capsule and cortical matter, which is usually axial in location.[21]

An oblique narrow slit reveals a conus. In advanced cases, subcapsular and localized cortical opacities can be observed. Retinoscopy reveals an oil droplet sign which is correlated with the scissor reflex. Scissoring is due to varied refraction in the central and peripheral areas of the lens. Retinal signs are seen as dot and fleck retinopathy with lozenge sign (dull reflex at the macular), which appear as white and yellow granulation that is located superficially.[22]

Less Common

In the cornea, posterior polymorphous dystrophy is seen, and endothelial vesicles are present in clusters (doughnuts) and bands (snail track).[23] Calcium deposit in the conjunctiva and sclera due to hypercalcemia (secondary to renal failure). Recurrent corneal erosions are present in the anterior cornea, and corneal opacity can be present. Other less common findings include microcornea, lenticonus posterior, cataractous changes in the lens, spontaneous anterior lens capsule rupture, central lamellar macular hole, macular thinning, foveal pigmentation disturbance, vitelliform maculopathy (bull's eye).[24]

Corneal signs of recurrent corneal erosions occur due to defective adhesions between the epithelium and Bowman's membrane. Corneal erosions are seen in individuals with early-onset renal failure and extrarenal features. Recurrent corneal erosions can be found in members of the same family, but they are not linked to specific mutations.[14]

Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy can also occur due to defective adhesion between layers. These patients complain of grittiness, watering, and photophobia. Patients with advanced pathology may require corneal transplantation. The majority of patients can be managed with symptomatic conservative management.[25]

These can be picked up on meticulous slit lamp examination, confocal microscopy, and anterior segment optical coherence tomography. Corneal arcus juvenilis can be one of the rare findings in association with Alport syndrome. Anterior Lenticonus The defect in collagen 4 causes the lens capsule's thinning and fragility, resulting in lenticonus. Electron microscopic studies have demonstrated multiple linear breaks in the inner 2/3 of the lens capsule containing fibrillar material and vacuoles. Apart from the histological changes seen in the anterior lens capsule, the weakened capsule is stressed during accommodative effort.[21]

This causes the anterior lens capsule to become more convex in the central portion, and occasionally the capsule may rupture. This complication can be managed by cataract surgery or lens removal. A well-centered, adequate continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis must be created during the surgery to manage the central protruded fragile lens capsule. The femtosecond laser-assisted capsule removal has been a safe procedure. The incidence of posterior lenticonus is less common. Most surgical procedures have been successful in this scenario despite the spontaneous capsular rupture before surgery.[26]

Retinopathy

The type IV collagen framework is seen in the internal limiting membrane and the RPE basement membrane in Bruch's membrane. The internal limiting membrane and Bruch's membrane are thinned out in Alport syndrome. The thinned-out membranes lead to retinopathy and macular hole formation.[27] Retinopathy is seen as dot and fleck white or yellow granules located superficially, giving rise to a "lozenge sign." Lozenge sign is described as a dull reflex at the macula as a result of the separation line between perimacular retinopathy and the thinned-out macula. It also represents a hyperreflective shadow on OCT and the nerve fiber layer in the area corresponding to nerve fiber layer distribution which denotes the location of the retinopathy. A thinner nerve fiber layer is more susceptible to traction from the vitreous and acts as a barrier for transporting nutrients and waste product clearance, the origin being the dot and fleck retinopathy.[27]

The retinopathy in the central part appears as scattered yellowish-white dots and flecks to a dense, confluent annulus around the region of the temporal thinned-out retina. The central and peripheral retinopathy have nearly exact pathogenesis in X-linked and autosomal recessive Alport syndrome. Retinopathy can dictate the prognosis in early onset renal failure if present. The major differential diagnosis of retinopathies is fundus albipunctatus and other causes of generalized drusen and pigmentary retinopathy. Temporal macular thinning and dot and fleck retinopathy do not affect vision. A macular hole can cause vision loss and a poor response to surgery.[27]

Systemic symptoms

The patient usually presents with symptoms of sensorineural hearing loss, hypertension, edema, and chronic haematuria.[3]

Diagnostic Clinical Signs

Alport Syndrome diagnosis rests on the following key clinical points

- Family history of Alport, glomerular haematuria, and no other cause for haematuria

- Bilateral SNHL, dot and fleck retinopathy, and lenticonus

- Lack of type 4 collagen in the glomerular basement membrane[28]

Posterior Lenticonus

Posterior lenticonus was first reported in 1888 by Meyer. According to certain authors, lenticonus posterior is a congenital defect usually isolated and not associated with any systemic disease. In sporadic cases, it usually presents as an isolated anomaly. In autosomal dominant inherited cases, there is typically bilateral involvement. The incidence of posterior lenticonus is more as compared to anterior lenticonus. The average age of diagnosis for posterior lenticonus is 3 to 7 years.[2] Unilateral infantile cataracts are more common, but rarely bilateral cataracts can also be seen. The reported prevalence is between 1-4 per 1 lakh children. The male-to-female ratio is nearly 1 to 1.

The diagnosis of posterior lenticonus is purely clinical, but it is cumbersome to diagnose asymptomatic cases. The essential diagnostic signs are the fishtail sign, in which a lens cortex is seen in the anterior vitreous phase after posterior capsular rent. The oil droplet sign and the atoll sign, in which there is an advanced posterior lenticonus and no posterior capsule defect, appear like an atoll. The term atoll has been taken from the Maldivian word atolu.[29]

The association of posterior lenticonus with Lowe syndrome has been explained by the Lyon hypothesis, which explains the deactivation of the X chromosome. In a mouse model, the development of posterior lenticonus with cataracts is explained by transcription of the co-activator ASC-2 molecule.[30]

The major associations of posterior lenticonus are Duane retraction syndrome, microphthalmos, keratoconus, microcornea, iris coloboma, lens coloboma, retinochoroidal coloboma, angle anomalies, anterior lenticonus, axial myopia, persistent hyaloid artery remnants, morning glory syndrome, retinoblastoma, Down syndrome, Alport and Lowe syndrome. Another syndrome is associated with posterior lenticonus s, MPPC syndrome, in which there is bilateral microcornea, posterior megalolenticonus, persistent fetal vasculature, and chorioretinal colobomas.[31]

The most common complication with posterior lenticonus is amblyopia. The other common associations of posterior lenticonus are amblyopia, cataract, strabismus, and loss of central fixation. Amblyopia results from optical distortions in the early oil droplet stage caused by anisometropia or cataract deprivation. It has been observed that with time, cataractous changes are seen at the level of the lenticonus, and they can spread to the adjacent subcapsular cortex quickly.[32]

Strabismus is a common sequela in patients with posterior lenticonus, and the incidence is related to the occurrence of sensory deprivation. Leukocoria is a vital sign in patients with lenticonus, and other causes of leukocoria, such as retinoblastoma and persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous, should be ruled out in these cases. Posterior lenticonus can also severely affect the visual acuity in children and may result in amblyopia. In cases where cycloplegic agents have been used, a bifocal correction on needed for near-visual tasks.[33]

Lowe Syndrome

Lowe syndrome, also called oculocerebrorenal syndrome (OCRL), is a rare genetic disorder associated with multiple male anomalies. The incidence is 1 in 500,000 population. Then systemic manifestations include mental retardation, muscular hypotonia, and renal dysfunction in the form of Fanconi syndrome.[33]

Ocular manifestations include posterior lenticonus, congenital cataract, corneal keloid, and infantile glaucoma. Lowe syndrome is an X-linked recessive disorder with mutations in the OCRL gene. The mutations in males are transmitted from a mother with an OCRL gene copy or if there is a new mutation spontaneously without any family history. The diagnosis of Lowe syndrome is governed by genetic testing and physical examination. There is a family history of males getting affected. The mothers of affected children may exhibit radial cortical lenticular opacities in the form of snowflakes.[34]

Ocular Findings

Cataracts can be present since birth, and Lowe syndrome should be kept as a differential for any child presenting with bilateral cataracts. Posterior lenticonus is another common association with Lowe syndrome. Visual prognosis is usually poor, with vision less than 20/100.[30]

Glaucoma is seen in approximately 50% of the patients. There is increased intraocular pressure with associated buphthalmos. There is a distorted anterior chamber angle which is seen in gonioscopy. Both scleral spurs have reduced visibility, and a narrowing of the ciliary body band is noted. Despite maximal medical therapy, glaucoma is progressive and non-responsive to medical therapy. Vision loss can lead to blindness in these patients. Nystagmus is due to aphakia and possibly due to retinal abnormalities from genetic mutations. Conjunctival and corneal keloids can further reduce visual prognosis.[35]

Neurological Problems

Hypotonia with loss of deep tendon reflexes. Labored and difficult breathing at birth. Reduced motor function is seen in these patients. Mental retardation is seen in these patients, along with maladaptive behavior such as irritability, temper tantrums, and non-finalized behavior. Patients can also have seizures and febrile convulsions.[36]

Renal Problems

Fanconi syndrome occurs in patients with Lowe syndrome, which develops with age and may be asymptomatic at birth. Electrolyte loss can lead to failure to survive. There is bicarbonate loss along with salt and water waste. Chronic renal failure may result as time progress. The renal tubular dysfunction is characterized by aminoaciduria, hypercalciuria, low molecular weight proteinuria, and occasional renal tubular acidosis.[37]

Evaluation

Ocular Evaluation

Visual Acuity

A routine visual acuity examination is mandatory in each case to document Snellen's uncorrected, best-corrected, and pinhole visual acuity.[38]

Subjective Refraction

Subject refraction should be documented to know astigmatism and rule out amblyopia. Regular documentation of refraction is necessary as these patients can have a sudden myopic shift.[39]

Cycloplegic Refraction

Cycloplegic refraction in a dilated pupil is an integral part of the workup of these patients to rule out amblyopia, and pupil dilatation is needed to provide refraction peripheral to the area of the lenticonus.[40]

Intraocular Pressure

To rule out pre-existing glaucoma, it is mandatory to document IOP in each case using non-contact tonometry or contact tonometry.[41]

Ultrasound B Scan

Ultrasound B scan reveals the existence and extent of lenticonus. On B scan, lenticonus appears as herniated lenticular material suggestive of lenticonus.[1]

Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography

ASOCT is mandated to assess the configuration of the anterior or posterior lenticonus and to know the integrity of the posterior capsule. In cases with pre-existing posterior capsular defects or posterior capsular dehiscence, ASOCT is a viable tool.[42]

Ultrasound Biomicroscopy

It is a helpful investigation to rule out lenticonus.[43]

A Scan

A scan documents keratometric value, astigmatism, and axial length and calculates the IOL power. A scan also documents increased lens thickness.[44]

IOL Master

In clinics where IOL master is available, it is a handy tool and more reliable for calculating IOL power.[45]

Neuroimaging

These patients suffer from neurological problems, so this warrants neuroimaging. MRI usually reveals light ventriculomegaly and periventricular cystic lesions.[46]

Laboratory Analysis

The lab diagnosis of Lowe syndrome rests on the reduction in inositol polyphosphate-5 phosphate activity of OCRL-1 cultured in skin fibroblasts. Genetic analysis for OCLR gene. Electromyography and electroencephalography to assess neurologic and musculoskeletal sequelae. Serology to rule out metabolic acidosis, reduced glomerular function, hypovitaminosis D, raised CPK, and liver transaminases. Urine analysis will reveal aminoaciduria and proteinuria.[47]

Systemic Evaluation

Audiometry

Audiometry is a vital tool for assessing hearing loss and the type of hearing loss. Alport usually has high-tone bilateral sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL). The hearing loss is most pronounced at a frequency of 2000 and 8000 Hz, which makes it difficult to distinguish sounds, and there is increased sensitivity to loud noise, which is characteristic.[48]

Blood Pressure Assessment

It is mandatory to assess blood pressure in these patients as these cases are prone to renal hypertension.[49]

Complete Blood Count

To complete the list and assess the patient holistically, CBC is needed for these cases.[50]

Kidney Function Test

Patients with Alport have chronic haematuria, edema, hypertension, and glomerulonephritis; hence kidney function test is mandated in these cases.[51]

Urine Analysis

Routine urine analysis is essential to rule out microalbuminuria/proteinuria. [52]

Ultrasound Abdomen

It will reveal renal parenchymal disease.[53]

Renal Biopsy

To assess the GBM ultrastructural characteristics, collagen 4 composition, and extent of glomerular damage.[54]

Genetic Analysis

To know the lamellated GBM, a COL4A5 mutation and two COL4A3 or COL4A4 mutations.[55]

Treatment / Management

Screening

Family members of X-linked Alport syndrome patients need screening. The family members need screening on at least two different occasions and must be screened for other tests. The other causes of haematuria must be excluded.[56]

Genetic Testing and Counselling

Genetic testing and counseling must be stressed if mutations are detected in other family members.[57]

General treatment

Treatment usually delays the progression of end-stage renal disease (ESRD), which can reverse the lenticonus clinical condition and the need for a renal transplant.[57]

Medical Management

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and aldosterone inhibitors reduce proteinuria. A renal transplant is required in end-stage renal disease and renal failure. Corneal erosions can be managed with a pad, bandage, topical antibiotics, and pain relief. In cases with advanced corneal disease, corneal transplantation is required. Lens aspiration and IOL implantation are necessary for patients with lenticonus and cataracts. Observation is mandated in fleck retinopathy and hearing aids for SNHL. Macular hole surgery has a poor prognosis in these cases.[58]

Follow-Up

Timely and regular follow-up is required in Alport syndrome cases to control risk factors, renal failure, and reduced symptoms of hypertension, proteinuria, and hematuria in the entire life span. Ototoxic medications should be avoided, and exposure to high noise should be reduced.[7]

Indications of surgery in cases with lenticonus

- Best corrected visual acuity of 20/100 or less

- Loss of central fixation

- Non-resolving amblyopia[59] (B3)

Ocular Management

In cases with early lenticonus where visual acuity is not affected with good best corrected visual acuity, spectacle or contact lens can be prescribed. These patients are followed up closely to rule out the sudden change in visual acuity due to the development of cataracts or spontaneous rupture of lenticonus.[29](B3)

Lens Removal/ Aspiration

In cases where lenticonus is causing a reduction in visual acuity, removing the lens and implanting an IOL is imperative. The IOL power is decided based on the age of the patient. In cases with posterior lenticonus, it is essential to check the integrity of the posterior capsule and rule out posterior capsular dehiscence. Managing posterior capsular dehiscence can be a challenge under certain scenarios, and in these cases, IOL should be placed in the sulcus.[60]

Anterior Vitrectomy

A thorough anterior vitrectomy is required in pediatric cases where posterior capsulorhexis has been performed. The vitreous must be cleared before implanting an IOL.[61](B3)

Posterior Capsulorhexis

This is required in pediatric cases to avoid posterior capsular opacification.[62]

Pars Plana Vitrectomy

This is needed in cases where there is cortical matter in the vitreous cavity or in extreme cases where there is a nucleus or IOL drop.[63]

Occlusion Therapy

This is required in pediatric cases with amblyopia once the visual axis has been cleared.[64]

YAG Capsulotomy

This is needed in cases with posterior capsular opacification.[65]

Topical Steroids

Topical steroids such as prednisolone 1% or dexamethasone 0.1% are needed in tapered doses of 6,5,4,3,2,1 for one week each to manage post-cataract surgery inflammation.[66]

Lowe Syndrome

Ocular

Lowe syndrome patients having cataracts and lenticonus are treated within the first 6-8 weeks of life to prevent the development of amblyopia. The patients are left aphakic for the first two years to avoid developing irregular complications such as glaucoma. Glasses and contact lenses are needed for visual development. Lowe syndrome patients may develop irreversible glaucoma and require surgical intervention. Goniotomy, trabeculectomy, and tube shunts may be necessary for these patients.[67]

Systemic

Hypotonia in Lowe syndrome early physical intervention. Antipsychotics control maladaptive behavior. Neurological problems require treatment with clomipramine, paroxetine, and risperidone. Renal tubular acidosis is treated with sodium bicarbonate and another alkali. Intravenous fluid is necessary in cases of dehydration. Vitamin D supplement is required to prevent rickets and closely monitor parathyroid hormone and calcium levels.[68]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for a case of lenticonus include

- Alport syndrome

- Lowe syndrome

- Lentiglobus

- Thin basement membrane nephropathy

- Leber congenital optic neuropathy

- Zellweger syndrome

- Congenital infections- rubella, toxoplasmosis

- Congenital myotonic dystrophies

- Congenital myopathy- muscle-eye-brain disease

- Joubert syndrome

- Fundus albipunctatus

- Pigmentary retinopathy

Prognosis

Ocular Prognosis

The ocular prognosis in anterior and posterior lenticonus cases is usually good if managed on time. If there is a spontaneous rupture of lenticonus, it can result in secondary glaucoma. The prognosis can be guarded in such neglected cases. In cases with the posterior capsular breach, if the case is managed well, the IOL can be implanted in the sulcus, or an optic capture can be performed. The prognosis is usually good in such cases. Lowe syndrome visual prognosis depends on glaucoma, strabismus, and amblyopia development.[5]

Systemic Prognosis

In patients with XL Alport syndrome in males, end-stage renal disease can be seen in 90% of the cases and 12% of females by the age of 40. Renal transplantation in Alport patients, if performed on time, has good graft and patient survival in comparison to those caused by other causes. Cases with autosomal recessive Alport syndrome have an early incidence of renal failure compared to autosomal dominant Alport syndrome. Lowe syndrome's prognosis is variable, and early and prompt diagnosis is essential to prevent life-threatening complications such as hypotony, infection, and renal pathology. The quality of life is governed by the extent of kidney and nervous compromise.[69]

Cheng et al. treated 41 eyes with posterior lenticonus by surgical aspiration of the lens, IOL implantation, and amblyopia management. The visual acuity improved by two or more Snellen's visual acuity in 43% of the patients tested at six months. A total of 19 eyes improved visual acuity postoperatively by 20/20 to 20/40. Long-term follows up reveals that amblyopia remains a significant cause of loss of visual acuity for which occlusion therapy is required.[32]

Bradford et al. reported excellent results of occlusion therapy in patients with partial cataracts and very poor outcomes in patients with posterior lenticonus. Prompt diagnosis and meticulous management improve diagnosis and prevent early-onset renal failure. Lee et al. reported that a pre-existing PC defect has a significantly better visual outcome than patients with posterior polar opacity. They proposed that there is a faster progression of cataracts in patients with posterior capsular dehiscence leading to early diagnosis and prompt intervention leading to an excellent visual outcome.[70]

Complications

- Strabismus

- Cataract

- Loss of central fixation

- Amblyopia

- Spontaneous rupture of lenticonus

- Pigment dispersion syndrome

- Hyphema

- Microhyphema

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

All patients undergoing lens aspiration, cataract surgery, and IOL implantation should be started on steroids and adjuvant drugs to manage surgery-induced inflammation. The patient should be evaluated on postoperative day one and day 30. In case of any untoward complication or reduced visual acuity postoperatively, the patient can have a more frequent evaluation in the first and second week postoperatively. The patient should be told to avoid water splashes in the eyes for at least a month post-surgery. Counseling should be stressed.[71]

Consultations

Any patient with a suspected diagnosis of lenticonus should be referred to a pediatric ophthalmologist or a cataract and IOL specialist to delineate the lenticonus and decide on further surgical intervention. A retina consultation with a vitreoretinal specialist is mandatory in case of posterior capsular breach and cortical matter drop. If the patient develops secondary glaucoma, a specialist consultation can be sought. Lowe syndrome and Alport syndrome patients should regularly consult with a nephrologist, and Lowe syndrome should also visit a neurologist if needed.[72]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Every patient should be explained the ocular condition and the need for surgical intervention. The patient should be explained the surgical technique and the risks and complications associated with the surgery. Moreover, the need for regular and timely ocular examination should be emphasized. The patient should also be explained the importance of timely application of ocular medications and regular follow-up. The patient should also be explained the systemic pathology of Alport and Lowe syndrome and the need for appropriate consultations.[73]

Pearls and Other Issues

Anterior lenticonus is an acquired ocular disorder usually associated with Alport syndrome, and posterior lenticonus is an isolated ocular pathology that is congenital. Patients with lenticonus should be examined holistically to decide whether the eye needs surgical intervention.[2]

A systemic examination is mandatory in these cases to rule out life-threatening sequelae. The visual outcome is usually good in these cases, and visual acuity improves after IOL implantation. It is vital to implant foldable IOL in the bag or the sulcus in cases with pre-existing posterior capsular defects or deficiencies. Children having amblyopia and strabismus usually have poor outcomes.[74]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Anterior and posterior lenticonus patients need timely and appropriate intervention to prevent irreversible ocular and systemic sequelae.[2] The ophthalmologist plays a crucial role in diagnosing and managing lenticonus cases; the optometrist help to ascertain the induced refractive error and induced myopic shift, and the nursing staff help in patient recruitment, counseling, and support in the operating room—the pharmacist help in procuring and dispensing appropriate medications. The nephrologist and neurologist also play a crucial role in properly evaluating and treating these patients.[2]

These various disciplines need to function like a cohesive interprofessional team; this approach to care will result in the best patient outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Jacobs K, Meire FM. Lenticonus. Bulletin de la Societe belge d'ophtalmologie. 2000:(277):65-70 [PubMed PMID: 11126676]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHalawani LM, Abdulaal MF, Alotaibi HA, Alsaati AF, Bin Dakhil TA. Development of Posterior Lenticonus Following the Diagnosis of Isolated Anterior Lenticonus in Alport Syndrome. Cureus. 2021 Jan 28:13(1):e12970. doi: 10.7759/cureus.12970. Epub 2021 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 33659118]

Watson S, Padala SA, Hashmi MF, Bush JS. Alport Syndrome. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262041]

Gupta V,Jamil M,Luthra S,Puthalath AS, Alport syndrome with bilateral simultaneous anterior and posterior lenticonus with severe temporal macular thinning. BMJ case reports. 2019 Aug 15; [PubMed PMID: 31420426]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAl-Mahmood AM, Al-Swailem SA, Al-Khalaf A, Al-Binali GY. Progressive posterior lenticonus in a patient with alport syndrome. Middle East African journal of ophthalmology. 2010 Oct:17(4):379-81. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.71591. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21180444]

Bamotra RK, Meenakshi, Kesarwani PC, Qayum S. Simultaneous Bilateral Anterior and Posterior Lenticonus in Alport Syndrome. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2017 Aug:11(8):ND01-ND02. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/25521.10369. Epub 2017 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 28969174]

Warady BA, Agarwal R, Bangalore S, Chapman A, Levin A, Stenvinkel P, Toto RD, Chertow GM. Alport Syndrome Classification and Management. Kidney medicine. 2020 Sep-Oct:2(5):639-649. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2020.05.014. Epub 2020 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 33094278]

Savige J,Colville D,Rheault M,Gear S,Lennon R,Lagas S,Finlay M,Flinter F, Alport Syndrome in Women and Girls. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2016 Sep 7; [PubMed PMID: 27287265]

Colville DJ, Savige J. Alport syndrome. A review of the ocular manifestations. Ophthalmic genetics. 1997 Dec:18(4):161-73 [PubMed PMID: 9457747]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSavige J, Sheth S, Leys A, Nicholson A, Mack HG, Colville D. Ocular features in Alport syndrome: pathogenesis and clinical significance. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2015 Apr 7:10(4):703-9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10581014. Epub 2015 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 25649157]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBoutaud A, Borza DB, Bondar O, Gunwar S, Netzer KO, Singh N, Ninomiya Y, Sado Y, Noelken ME, Hudson BG. Type IV collagen of the glomerular basement membrane. Evidence that the chain specificity of network assembly is encoded by the noncollagenous NC1 domains. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000 Sep 29:275(39):30716-24 [PubMed PMID: 10896941]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShoulders MD, Raines RT. Collagen structure and stability. Annual review of biochemistry. 2009:78():929-58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.032207.120833. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19344236]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSridhar MS. Anatomy of cornea and ocular surface. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Feb:66(2):190-194. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_646_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29380756]

Miller DD, Hasan SA, Simmons NL, Stewart MW. Recurrent corneal erosion: a comprehensive review. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2019:13():325-335. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S157430. Epub 2019 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 30809089]

Dezhagah H. Circular anterior lens capsule rupture caused by blunt ocular trauma. Middle East African journal of ophthalmology. 2010 Jan:17(1):103-5. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.61227. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20543947]

Khokhar S, Dhull C, Mahalingam K, Agarwal P. Posterior lenticonus with persistent fetal vasculature. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Sep:66(9):1335-1336. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_276_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30127164]

Sonarkhan S, Ramappa M, Chaurasia S, Mulay K. Bilateral anterior lenticonus in a case of Alport syndrome: a clinical and histopathological correlation after successful clear lens extraction. BMJ case reports. 2014 Jun 26:2014():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-202036. Epub 2014 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 24969069]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNozu K, Nakanishi K, Abe Y, Udagawa T, Okada S, Okamoto T, Kaito H, Kanemoto K, Kobayashi A, Tanaka E, Tanaka K, Hama T, Fujimaru R, Miwa S, Yamamura T, Yamamura N, Horinouchi T, Minamikawa S, Nagata M, Iijima K. A review of clinical characteristics and genetic backgrounds in Alport syndrome. Clinical and experimental nephrology. 2019 Feb:23(2):158-168. doi: 10.1007/s10157-018-1629-4. Epub 2018 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 30128941]

Ghosh S,Singh M,Sahoo R,Rao S, Alport syndrome: a rare cause of uraemia. BMJ case reports. 2014 Feb 13; [PubMed PMID: 24526194]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTatham A, Prydal J. Progressive lenticular astigmatism in the clear lens. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 2008 Mar:34(3):514-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.10.023. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18299081]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMartin R. Cornea and anterior eye assessment with slit lamp biomicroscopy, specular microscopy, confocal microscopy, and ultrasound biomicroscopy. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Feb:66(2):195-201. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_649_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29380757]

Al-Mahrouqi H, Oraba SB, Al-Habsi S, Mundemkattil N, Babu J, Panchatcharam SM, Al-Saidi R, Al-Raisi A. Retinoscopy as a Screening Tool for Keratoconus. Cornea. 2019 Apr:38(4):442-445. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001843. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30640248]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBrooks AM,Grant G,Gillies WE, Differentiation of posterior polymorphous dystrophy from other posterior corneal opacities by specular microscopy. Ophthalmology. 1989 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 2616149]

Bernauer W, Thiel MA, Kurrer M, Heiligenhaus A, Rentsch KM, Schmitt A, Heinz C, Yanar A. Corneal calcification following intensified treatment with sodium hyaluronate artificial tears. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2006 Mar:90(3):285-8 [PubMed PMID: 16488945]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuier CP, Patel BC, Stokkermans TJ, Gulani AC. Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613630]

Sharma B, Abell RG, Arora T, Antony T, Vajpayee RB. Techniques of anterior capsulotomy in cataract surgery. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2019 Apr:67(4):450-460. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1728_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30900573]

Savige J,Liu J,DeBuc DC,Handa JT,Hageman GS,Wang YY,Parkin JD,Vote B,Fassett R,Sarks S,Colville D, Retinal basement membrane abnormalities and the retinopathy of Alport syndrome. Investigative ophthalmology [PubMed PMID: 19850830]

Haldar I, Jeloka T. Alport's Syndrome: A Rare Clinical Presentation with Crescents. Indian journal of nephrology. 2020 Mar-Apr:30(2):129-131. doi: 10.4103/ijn.IJN_177_19. Epub 2020 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 32269440]

Medsinge A, Nischal KK. Pediatric cataract: challenges and future directions. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2015:9():77-90. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S59009. Epub 2015 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 25609909]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTripathi RC, Cibis GW, Tripathi BJ. Pathogenesis of cataracts in patients with Lowe's syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1986 Aug:93(8):1046-51 [PubMed PMID: 3763153]

Mittal V,Gupta A,Sachdeva V,Kekunnaya R, Duane retraction syndrome with posterior microphthalmos: a rare association. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 2012 Aug 7; [PubMed PMID: 22881831]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCheng KP, Hiles DA, Biglan AW, Pettapiece MC. Management of posterior lenticonus. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 1991 May-Jun:28(3):143-9; discussion 150 [PubMed PMID: 1890571]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBui Quoc E, Milleret C. Origins of strabismus and loss of binocular vision. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience. 2014:8():71. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2014.00071. Epub 2014 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 25309358]

Abdolrahimzadeh S, Fameli V, Mollo R, Contestabile MT, Perdicchi A, Recupero SM. Rare Diseases Leading to Childhood Glaucoma: Epidemiology, Pathophysiogenesis, and Management. BioMed research international. 2015:2015():781294. doi: 10.1155/2015/781294. Epub 2015 Sep 16 [PubMed PMID: 26451378]

Raluca M,Mircea F,Andrei F,Carmen D,Miruna N,Grigorios T,Ileana U, Old and new in exploring the anterior chamber angle. Romanian journal of ophthalmology. 2015 Oct-Dec; [PubMed PMID: 29450309]

Leyenaar J, Camfield P, Camfield C. A schematic approach to hypotonia in infancy. Paediatrics & child health. 2005 Sep:10(7):397-400 [PubMed PMID: 19668647]

Karatzas A, Paridis D, Kozyrakis D, Tzortzis V, Samarinas M, Dailiana Z, Karachalios T. Fanconi syndrome in the adulthood. The role of early diagnosis and treatment. Journal of musculoskeletal & neuronal interactions. 2017 Dec 1:17(4):303-306 [PubMed PMID: 29199190]

Caltrider D, Gupta A, Tripathy K. Evaluation of Visual Acuity. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33231977]

Gurnani B,Kaur K, Astigmatism. StatPearls. 2022 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 35881747]

Kaur K, Gurnani B. Cycloplegic and Noncycloplegic Refraction. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 35593830]

Brusini P, Salvetat ML, Zeppieri M. How to Measure Intraocular Pressure: An Updated Review of Various Tonometers. Journal of clinical medicine. 2021 Aug 27:10(17):. doi: 10.3390/jcm10173860. Epub 2021 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 34501306]

Yu SS, Lu CZ, Guo YW, Zhao Y, Yuan XY. Anterior segment OCT application in quantifying posterior capsule opacification severity with varied intraocular lens designs. International journal of ophthalmology. 2021:14(9):1384-1391. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2021.09.13. Epub 2021 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 34540614]

Sedaghat MR,Momeni-Moghaddam H,Haghighi B,Moshirfar M, Phacoemulsification in bilateral anterior lenticonus in Alport syndrome: A case report. Medicine. 2019 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 31574802]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGhiasian L, Abolfathzadeh N, Manafi N, Hadavandkhani A. Intraocular lens power calculation in keratoconus; A review of literature. Journal of current ophthalmology. 2019 Jun:31(2):127-134. doi: 10.1016/j.joco.2019.01.011. Epub 2019 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 31317089]

De Bernardo M, Cione F, Capasso L, Coppola A, Rosa N. A formula to improve the reliability of optical axial length measurement in IOL power calculation. Scientific reports. 2022 Nov 7:12(1):18845. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-23665-0. Epub 2022 Nov 7 [PubMed PMID: 36344612]

Todd KL, Brighton T, Norton ES, Schick S, Elkins W, Pletnikova O, Fortinsky RH, Troncoso JC, Molfese PJ, Resnick SM, Conover JC, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Ventricular and Periventricular Anomalies in the Aging and Cognitively Impaired Brain. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2017:9():445. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00445. Epub 2018 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 29379433]

Suchy SF, Olivos-Glander IM, Nussabaum RL. Lowe syndrome, a deficiency of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate 5-phosphatase in the Golgi apparatus. Human molecular genetics. 1995 Dec:4(12):2245-50 [PubMed PMID: 8634694]

Salmon MK, Brant J, Hohman MH, Leibowitz D. Audiogram Interpretation. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 35201707]

Pugh D, Gallacher PJ, Dhaun N. Management of Hypertension in Chronic Kidney Disease. Drugs. 2019 Mar:79(4):365-379. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-1064-1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30758803]

Zamanzadeh V,Jasemi M,Valizadeh L,Keogh B,Taleghani F, Effective factors in providing holistic care: a qualitative study. Indian journal of palliative care. 2015 May-Aug; [PubMed PMID: 26009677]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHorváth O, Szabó AJ, Reusz GS. How to define and assess the clinically significant causes of hematuria in childhood. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany). 2023 Aug:38(8):2549-2562. doi: 10.1007/s00467-022-05746-4. Epub 2022 Oct 19 [PubMed PMID: 36260163]

Toto RD. Microalbuminuria: definition, detection, and clinical significance. Journal of clinical hypertension (Greenwich, Conn.). 2004 Nov:6(11 Suppl 3):2-7 [PubMed PMID: 15538104]

Preston RA, Epstein M. Renal parenchymal disease and hypertension. Seminars in nephrology. 1995 Mar:15(2):138-51 [PubMed PMID: 7777724]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCosgrove D,Liu S, Collagen IV diseases: A focus on the glomerular basement membrane in Alport syndrome. Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology. 2017 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 27576055]

Liu JH, Wei XX, Li A, Cui YX, Xia XY, Qin WS, Zhang MC, Gao EZ, Sun J, Gao CL, Liu FX, Wu QY, Li WW, Asan, Liu ZH, Li XJ. Novel mutations in COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5 in Chinese patients with Alport Syndrome. PloS one. 2017:12(5):e0177685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177685. Epub 2017 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 28542346]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChan MM, Gale DP. Isolated microscopic haematuria of glomerular origin: clinical significance and diagnosis in the 21st century. Clinical medicine (London, England). 2015 Dec:15(6):576-80. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.15-6-576. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26621952]

Meiser B, Tucker K, Friedlander M, Barlow-Stewart K, Lobb E, Saunders C, Mitchell G. Genetic counselling and testing for inherited gene mutations in newly diagnosed patients with breast cancer: a review of the existing literature and a proposed research agenda. Breast cancer research : BCR. 2008:10(6):216. doi: 10.1186/bcr2194. Epub 2008 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 19090970]

Galle J, Reduction of proteinuria with angiotensin receptor blockers. Nature clinical practice. Cardiovascular medicine. 2008 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 18580865]

Chen AM, Cotter SA. The Amblyopia Treatment Studies: Implications for Clinical Practice. Advances in ophthalmology and optometry. 2016 Aug:1(1):287-305. doi: 10.1016/j.yaoo.2016.03.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28435934]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJammal HM, Khader Y, Shawer R, Al Bdour M. Posterior segment causes of reduced visual acuity after phacoemulsification in eyes with cataract and obscured fundus view. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2012:6():1843-8. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S38303. Epub 2012 Nov 7 [PubMed PMID: 23152664]

Sukhija J, Kaur S, Korla S. Posterior optic capture of intraocular lens in difficult cases of pediatric cataract. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2022 Jan:70(1):293-295. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1588_21. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34937259]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRaj SM,Vasavada AR,Johar SR,Vasavada VA,Vasavada VA, Post-operative capsular opacification: a review. International journal of biomedical science : IJBS. 2007 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 23675049]

Gurunadh VS, Banarji A, Ahluwalia TS, Upadhyay AK, Patyal S. Management of Nucleus and IOL Drop. Medical journal, Armed Forces India. 2008 Oct:64(4):315-6. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(08)80007-X. Epub 2011 Jul 21 [PubMed PMID: 27688565]

Park SH, Current Management of Childhood Amblyopia. Korean journal of ophthalmology : KJO. 2019 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 31833253]

Konopińska J, Młynarczyk M, Dmuchowska DA, Obuchowska I. Posterior Capsule Opacification: A Review of Experimental Studies. Journal of clinical medicine. 2021 Jun 27:10(13):. doi: 10.3390/jcm10132847. Epub 2021 Jun 27 [PubMed PMID: 34199147]

Solomon KD, Sandoval HP, Potvin R. Comparing Combination Drop Therapy to a Standard Drop Regimen After Routine Cataract Surgery. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2020:14():1959-1965. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S260926. Epub 2020 Jul 10 [PubMed PMID: 32764861]

Eibenberger K,Rezar-Dreindl S,Pusch F,Schmidt-Erfurth U,Stifter E, Management of cataract surgery in Lowe syndrome. International journal of ophthalmology. 2022; [PubMed PMID: 35919319]

MacKenzie NE, Kowalchuk C, Agarwal SM, Costa-Dookhan KA, Caravaggio F, Gerretsen P, Chintoh A, Remington GJ, Taylor VH, Müeller DJ, Graff-Guerrero A, Hahn MK. Antipsychotics, Metabolic Adverse Effects, and Cognitive Function in Schizophrenia. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2018:9():622. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00622. Epub 2018 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 30568606]

Kelly YP, Patil A, Wallis L, Murray S, Kant S, Kaballo MA, Casserly L, Doyle B, Dorman A, O'Kelly P, Conlon PJ. Outcomes of kidney transplantation in Alport syndrome compared with other forms of renal disease. Renal failure. 2017 Nov:39(1):290-293. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2016.1262266. Epub 2016 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 27917694]

Bradford GM, Kutschke PJ, Scott WE. Results of amblyopia therapy in eyes with unilateral structural abnormalities. Ophthalmology. 1992 Oct:99(10):1616-21 [PubMed PMID: 1454331]

Hoffman RS, Braga-Mele R, Donaldson K, Emerick G, Henderson B, Kahook M, Mamalis N, Miller KM, Realini T, Shorstein NH, Stiverson RK, Wirostko B, ASCRS Cataract Clinical Committee and the American Glaucoma Society. Cataract surgery and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 2016 Sep:42(9):1368-1379. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2016.06.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27697257]

Jain DH,Agarkar S,Dhillon HK, Clinical profile and surgical outcomes in children with posterior lenticonus. Oman journal of ophthalmology. 2021 Jan-Apr; [PubMed PMID: 34084033]

Allen D, Vasavada A. Cataract and surgery for cataract. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2006 Jul 15:333(7559):128-32 [PubMed PMID: 16840470]

Hennig A, Puri LR, Sharma H, Evans JR, Yorston D. Foldable vs rigid lenses after phacoemulsification for cataract surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Eye (London, England). 2014 May:28(5):567-75. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.26. Epub 2014 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 24556879]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence