Introduction

Epistaxis is one of the most common nasal emergencies, with roughly 1.7 emergency department visits per 1000 patients yearly.[1][2] Typically, anterior epistaxis is a benign self-limited event or resolves by applying direct pressure. Pediatric and elderly populations are most commonly affected by epistaxis, frequently due to direct trauma from nose picking or foreign body insertion, friable mucosa, or anticoagulant use with or without hypertension.[1] In the young and middle-aged adult population, another common cause of epistaxis is intranasal drug use, be it pharmaceutical, such as intranasal steroids, or recreational, such as cocaine.

Generally, anterior epistaxis is more common in winter in all age groups; air from heating systems dries the nasal mucosa, making it more prone to irritation and bleeding.[1] If the direct application of pressure for 15 to 20 minutes fails to achieve hemostasis, other methods are available to stop the bleeding. Vasoconstrictive agents and silver nitrate cautery may be applied, but nasal packing may be necessary if epistaxis persists despite these interventions.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

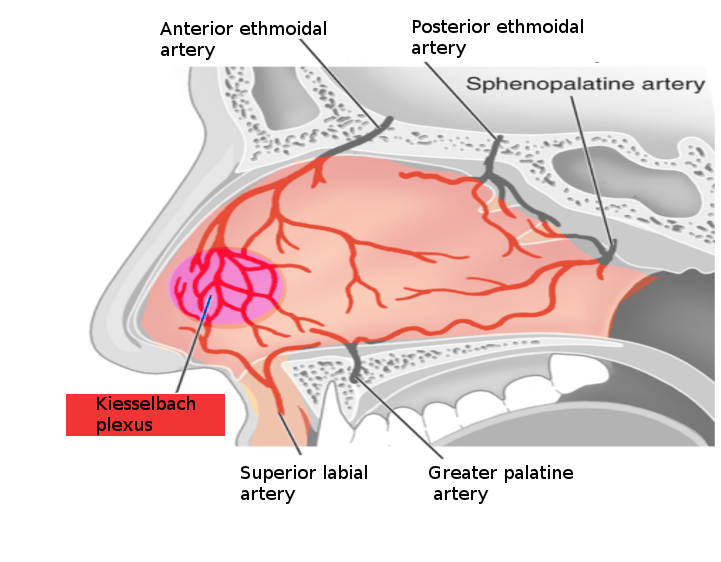

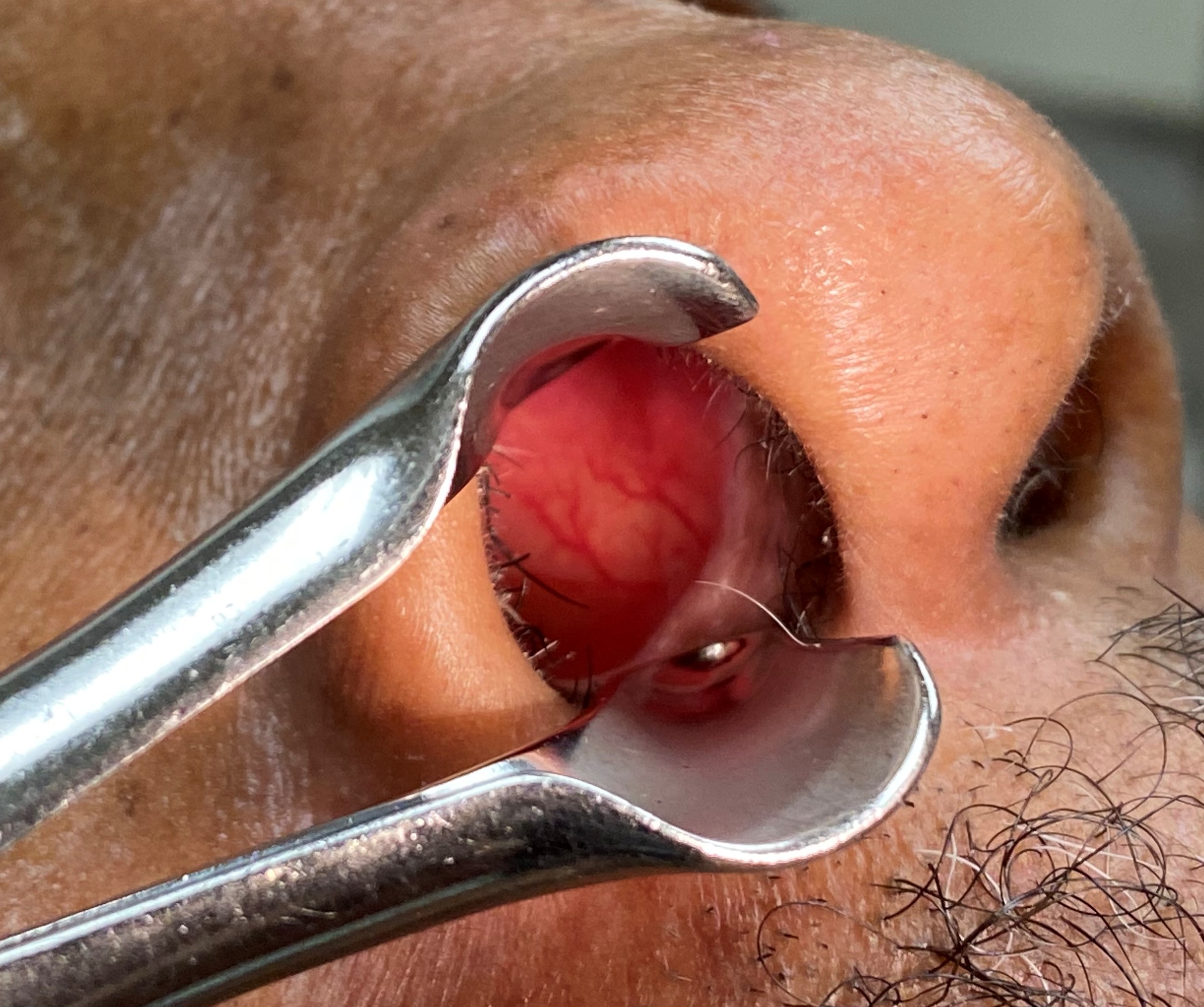

The most commonly implicated arterial blood supply in anterior epistaxis is the Kiesselbach plexus in Little’s area (Image 1).[2] This plexus is located on the anteroinferior nasal septum, just above the vestibule, and is readily visible during anterior rhinoscopy (Image 2). The Kiesselbach plexus comprises the anterior ethmoidal branch of the ophthalmic artery, the sphenopalatine branch of the maxillary artery, the superior labial branch of the facial artery, and the greater palatine branch of the maxillary artery. The ethmoidal arteries arise from the internal carotid system, while the sphenopalatine, greater palatine, and superior labial arteries are terminal branches of the external carotid system. These arteries supply the nasal mucosa and the underlying bone and cartilage, the latter via perichondrial microvasculature.

Over 90% of epistaxis originates on the anterior nasal septum; dangerous bleeding may occur posteriorly.[3][4] Posterior arterial epistaxis may be more challenging to manage; this diagnosis is typically made after excluding an anterior bleeding source via unsuccessful completion of the anterior epistaxis management algorithm. Posterior nasal packing also requires longer packs and more post-procedure monitoring than anterior nasal packing.[5] Posterior arterial epistaxis most commonly originates from terminal branches of the internal maxillary artery, such as the sphenopalatine, posterior lateral nasal, and posterior septal arteries.[6] Posterior venous epistaxis may originate from the Woodruff plexus, a submucosal venous network on the posterolateral wall of the nasal cavity, anterior to the nasopharynx and posterior to the inferior turbinate.[7]

In many cases, epistaxis is not simply the result of trauma but a manifestation of an underlying medical problem such as coagulopathy or platelet dysfunction. Identifying and correcting any underlying hematologic pathology will improve the success of any hemostatic intervention. Patients may bleed for various atraumatic reasons, including hypertension, thrombocytopenia, hemophilia, and the use of aspirin, chemotherapy, or herbal supplements, especially turmeric. Control of blood pressure and administration of fresh frozen plasma or platelets may mean the difference between success and failure of nasal packing. Other specific interventions may be required in some cases, such as administering vitamin K to correct a warfarin overdose or desmopressin in von Willebrand disease.

Indications

In the emergency department, nasal packing for anterior epistaxis is indicated for bleeding that is unresolved after the application of direct pressure, vasoconstrictive medications, or cautery. Nasal packing may also be placed for intraoperative or postoperative hemostasis.[8][9]

Contraindications

In the emergency department, nasal packing for anterior epistaxis is contraindicated in the setting of basilar skull fractures and significant facial or nasal bone fractures. Hemodynamic instability requiring emergency blood transfusion and airway compromise requiring intubation are relative contraindications. However, once stabilized, anterior nasal packing is permissible in patients with anterior epistaxis.

Equipment

Anterior nasal packing may require the following equipment and materials:

- A hospital bed with a back that can be positioned to 90 degrees

- Headlamp

- Otoscope

- Suction canister with either wall or portable suction

- Frazier suction tip

- Yankauer or Goodhill suction tip

- Nasal speculum

- Bayonet forceps

- Tongue depressor

- 4x4 inch gauze

- 2x2 inch gauze

- Dental roll

- Sterile lubricant

- Antibiotic ointment

- Intranasal vasoconstrictor

- Tranexamic acid

- Topical anesthetic

- Nasal tampon or intranasal packing device

- Personal protective equipment, including goggles, face mask, gown, and gloves

Personnel

A physician or advanced practice provider may perform anterior nasal packing in the urgent or emergent care setting. In austere conditions, packing may also be performed by a nurse or first responder.

Preparation

If the patient is actively bleeding from the nose, hemodynamically stable, and has a patent airway, vasoconstrictive agents such as 4% cocaine, 1% to 4% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine, or 0.05% oxymetazoline should be used to achieve hemostasis. After administering a vasoconstriction agent, the patient should be instructed to manually apply pressure for 15 to 20 minutes to the anterior nose, just behind the tip. Alternatively, a nasal clip can be used in the same location.

If bleeding persists despite these interventions, the patient should be placed in a “sniffing” position, sitting upright, flexing the neck, and extending the head. Both nares should be examined using a nasal speculum. If a large clot is present, it should be removed with suction to permit thorough visualization of the nasal cavity. If a discrete area of bleeding is visualized, cautery with silver nitrate may be attempted; this technique is usually unsuccessful if bleeding is significant. Electrocautery may be used for discrete, accessible bleeding if chemical cautery fails.

Nasal packing should be considered if these interventions fail to control epistaxis.

Technique or Treatment

Historically, anterior nasal packing was accomplished using a 6-foot length of petrolatum gauze packed using bayonet forceps into the affected naris to fill that side of the nasal cavity and tamponade the bleeding. However, this method has fallen out of favor with the advent of ready-made nasal packing devices.

Nasal pack devices of polyvinyl alcohol shaped like tampons with strings at the base are available in multiple sizes; 5.5 and 7.5 cm for adult anterior packs, 4.5 cm for children, and 9 cm for anterior-posterior packing. These devices expand on contact with moisture and apply pressure directly to the nasal mucosa. Multiple tampons may be placed simultaneously if the nasal cavity is large.

Another nasal pack device is an inflatable balloon with a covering of carboxymethylcellulose, which serves the double purpose of applying direct pressure and facilitating platelet aggregation.

Sedation and general anesthesia are typically avoided during nasal packing as they inhibit baseline airway-protective reflexes.

The initial steps in nasal packing with any agents are nearly identical and are outlined above. Nasal packing can begin after ensuring a patent and secure airway and achieving anesthesia with a vasoconstriction agent.[10][11][12][13][9]

Nasal tampons may need to be soaked in water for 30 seconds before insertion; this requirement is device-specific. Next, generously coat the tampon with antibiotic ointment or petroleum jelly. Insert the tampon into the affected naris by applying firm, steady pressure directed along the nasal floor, parallel to the ground; avoid insertion in a superior direction. While packing expansion frequently begins shortly after insertion, injecting approximately 10 mL of normal saline, 0.05% oxymetazoline, or tranexamic acid will expand the tampon and may help achieve hemostasis.

Inflatable balloon devices should also be generously coated with antibiotic ointment or petroleum jelly. Next, insert the deflated balloon into the nasal cavity as described above. Once the device is appropriately placed and following device-specific instructions, inflate the balloon with approximately 20 mL of air. It is critical to use air rather than water or saline because air is compressible and less likely to cause pressure necrosis of the nasal mucosa.

Monitor the patient for another 10 to 60 minutes to ensure hemostasis. The packing will likely turn pink as it absorbs the blood. If the patient continues to have active bleeding that turns the packing bright red or blood is visualized dripping out past the packing, or if the patient is still swallowing blood after 30 to 60 minutes, the filling has failed, and additional intervention, such as anterior-posterior packing, embolization, or surgery may be required.

Additional packs may be placed into the same naris as necessary to increase the amount of applied pressure. However, all attempts should be made to leave the initial pack in situ when adding additional packs. Pack placement and removal increase nasal mucosal trauma, worsening epistaxis, especially in patients with coagulopathies. Alternatively, the non-bleeding side may be packed to facilitate the application of pressure to the nasal septum. Contralateral nasal packing should be executed cautiously; excessive pressure on the nasal septum adversely affects the perichondrial microvascular circulation and may cause cartilage necrosis with resulting septal perforation.

Patients with anterior epistaxis successfully treated with nasal packing in the emergency department may be discharged and directed to follow up with the otolaryngologist in 24 to 48 hours for reassessment. Nasal packing may become a nidus for infection, and oral prophylactic antibiotics may be prescribed at the discretion of the clinician; antibiotic prophylaxis is not standard practice as no strong evidence suggests their administration prevents sinusitis or toxic shock syndrome.[14] Anterior nasal packs typically remain in place for at least 24 hours to achieve appropriate hemostasis. Early removal significantly increases the rebleeding risk. Nasal packing removal is typically performed in the otolaryngology office but may be performed in the emergency department if the patient cannot follow up with a specialist within 24 to 48 hours.

Patients With Underlying Coagulopathy

Patients with anterior epistaxis who are anticoagulated or coagulopathic pose a unique challenge to achieving hemostasis. Primary hemostasis is more difficult to achieve, and the risk of rebleeding with pack removal is increased even if removal is postponed for 72 hours. Correction of any concurrent bleeding disorders at the time of pack placement contributes to more effective hemostasis. Emergency medicine providers can ultimately achieve hemostasis in most of these patients; occasionally, it is necessary to consult the otolaryngology department or interventional radiology for further management.

In the emergency department, additional attempts to cauterize bleeding or repacking the naris with the addition of tranexamic acid typically results in successful hemostasis.[15] Some clinicians avoid using packs requiring removal in coagulopathic patients and opt for materials that absorb over time, such as cellulose mesh, hemostatic matrix, or sinusotomy absorbable nasal packing. These materials may not provide pressure as effectively as inflatable tampons or balloons. However, they are less likely to injure the mucosa during placement and cannot damage the mucosa on removal because removal is not required.

Complications

The most common complications of anterior nasal packing are pain with insertion or removal of the pack, rebleeding with pack removal, and failure to achieve hemostasis. Sanguineous nasolacrimal duct reflux manifested as bloody tears occurs rarely and is not a true complication, albeit one that patients may find distressing. Other complications of anterior nasal packing include but are not limited to excoriation or pressure necrosis of the nasal mucosa, infections such as sinusitis or toxic shock syndrome, migration of the packing, and aspiration.[16][17][18][19][20]

Posterior nasal packing increases the risk of airway obstruction and can induce a nasopulmonary reflex manifesting as bradycardia or respiratory depression due to increased nasopharyngeal pressure; patients are often admitted for continuous pulse oximetry. Excessive pressure in the nasopharynx may also result in necrosis of the soft palate, the prevention of which requires frequent examination.[5]

Clinical Significance

Although anterior epistaxis is typically self-limited, it can frighten patients and caregivers. As a result, patients often present with a high degree of anxiety. Therefore, it is essential for emergency medicine providers to be proficient and comfortable with nasal packing to perform it quickly and effectively. Being familiar with the equipment available at a given facility is also essential, as slight differences in products and materials can affect their employment.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

All emergency medicine providers must be proficient in evaluating and treating epistaxis. In addition, a strong working partnership among otolaryngologists and emergency department clinicians is necessary to provide specialty support for refractory cases and appropriate outpatient follow-up.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

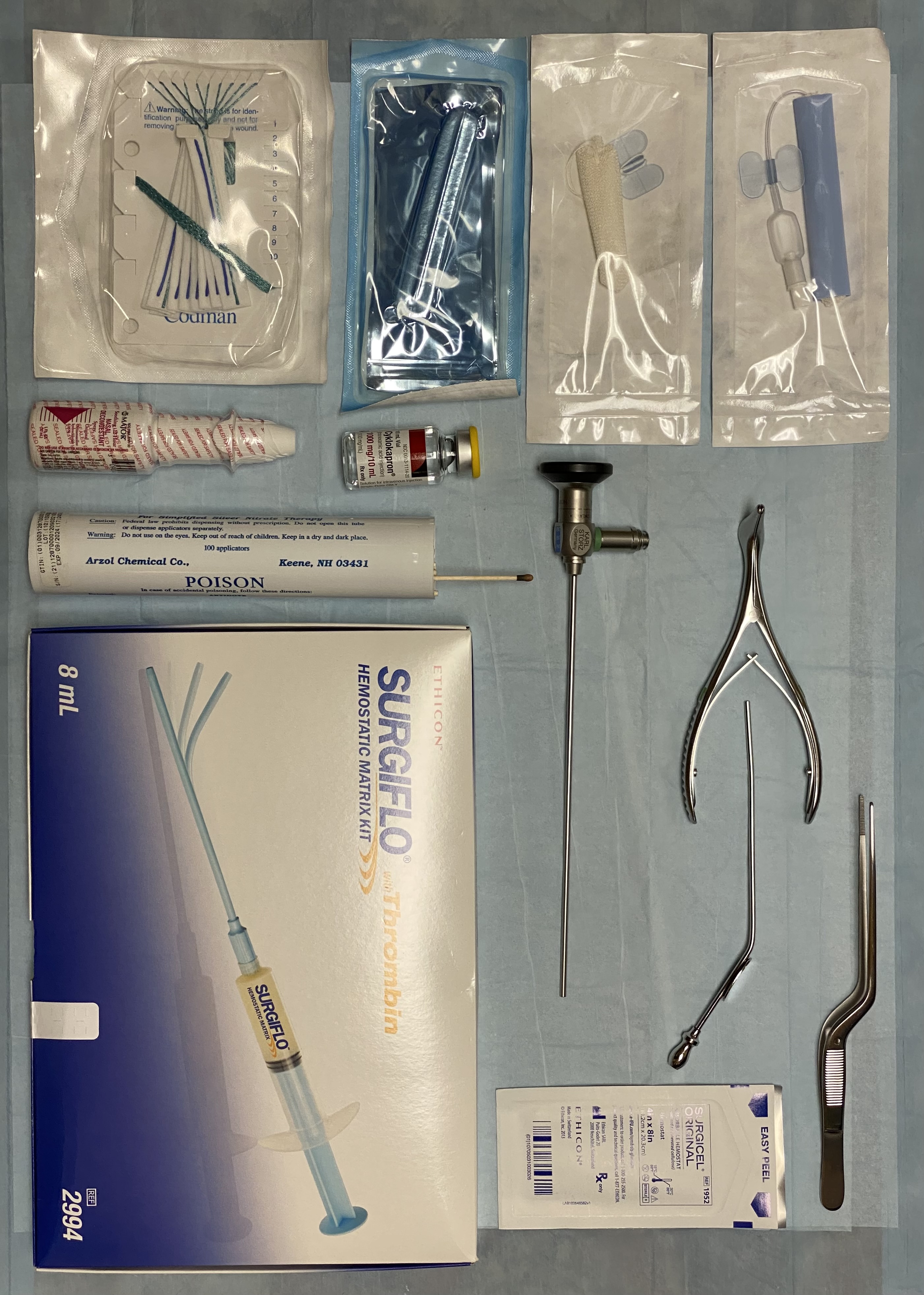

Supplies for Epistaxis Management. This set includes various tools and materials for managing epistaxis. The upper left corner features 2 packages— 5.5 cm and 7.5 cm inflatable anterior nasal packs. Below them are an uninflatable sponge anterior nasal pack and cottonoid pledgets, which can be soaked in oxymetazoline, epinephrine, or cocaine before use. The lower center includes tranexamic acid, oxymetazoline, and silver nitrate cautery sticks. In the lower right is a hemostatic matrix, with dissolvable cellulose packing positioned above it to the right. The set also includes essential tools such as Bayonet forceps, a Frazier suction tip, a Vienna speculum, and a 0-degree rigid Hopkins rod endoscope. A headlight is typically utilized for enhanced visualization.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

References

Pallin DJ, Chng YM, McKay MP, Emond JA, Pelletier AJ, Camargo CA Jr. Epidemiology of epistaxis in US emergency departments, 1992 to 2001. Annals of emergency medicine. 2005 Jul:46(1):77-81 [PubMed PMID: 15988431]

Tabassom A, Dahlstrom JJ. Epistaxis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613768]

Viducich RA, Blanda MP, Gerson LW. Posterior epistaxis: clinical features and acute complications. Annals of emergency medicine. 1995 May:25(5):592-6 [PubMed PMID: 7741333]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTunkel DE, Anne S, Payne SC, Ishman SL, Rosenfeld RM, Abramson PJ, Alikhaani JD, Benoit MM, Bercovitz RS, Brown MD, Chernobilsky B, Feldstein DA, Hackell JM, Holbrook EH, Holdsworth SM, Lin KW, Lind MM, Poetker DM, Riley CA, Schneider JS, Seidman MD, Vadlamudi V, Valdez TA, Nnacheta LC, Monjur TM. Clinical Practice Guideline: Nosebleed (Epistaxis). Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2020 Jan:162(1_suppl):S1-S38. doi: 10.1177/0194599819890327. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31910111]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLeadon M, Hohman MH. Posterior Epistaxis Nasal Pack. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 35015461]

Kasperek ZA, Pollock GF. Epistaxis: an overview. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2013 May:31(2):443-54. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2013.01.008. Epub 2013 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 23601481]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMorosanu CO, Humphreys C, Egerton S, Tierney CM. Woodruff's plexus-arterial or venous? Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2022 Jan:44(1):169-181. doi: 10.1007/s00276-021-02852-0. Epub 2021 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 34714375]

Zhou AH, Chung SY, Sylvester MJ, Zaki M, Svider PS, Hsueh WD, Baredes S, Eloy JA. To Pack or Not to Pack: Inpatient Management of Epistaxis in the Elderly. American journal of rhinology & allergy. 2018 Nov:32(6):539-545. doi: 10.1177/1945892418801259. Epub 2018 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 30270635]

Iqbal IZ, Jones GH, Dawe N, Mamais C, Smith ME, Williams RJ, Kuhn I, Carrie S. Intranasal packs and haemostatic agents for the management of adult epistaxis: systematic review. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2017 Dec:131(12):1065-1092. doi: 10.1017/S0022215117002055. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29280695]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHesham A, Ghali A. Rapid Rhino versus Merocel nasal packs in septal surgery. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2011 Dec:125(12):1244-6. doi: 10.1017/S0022215111002179. Epub 2011 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 21854674]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLeong SC, Roe RJ, Karkanevatos A. No frills management of epistaxis. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ. 2005 Jul:22(7):470-2 [PubMed PMID: 15983079]

Corbridge RJ, Djazaeri B, Hellier WP, Hadley J. A prospective randomized controlled trial comparing the use of merocel nasal tampons and BIPP in the control of acute epistaxis. Clinical otolaryngology and allied sciences. 1995 Aug:20(4):305-7 [PubMed PMID: 8548959]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBadran K, Malik TH, Belloso A, Timms MS. Randomized controlled trial comparing Merocel and RapidRhino packing in the management of anterior epistaxis. Clinical otolaryngology : official journal of ENT-UK ; official journal of Netherlands Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology & Cervico-Facial Surgery. 2005 Aug:30(4):333-7 [PubMed PMID: 16209675]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCohn B. Are prophylactic antibiotics necessary for anterior nasal packing in epistaxis? Annals of emergency medicine. 2015 Jan:65(1):109-11. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.08.011. Epub 2014 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 25220955]

Zahed R, Mousavi Jazayeri MH, Naderi A, Naderpour Z, Saeedi M. Topical Tranexamic Acid Compared With Anterior Nasal Packing for Treatment of Epistaxis in Patients Taking Antiplatelet Drugs: Randomized Controlled Trial. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2018 Mar:25(3):261-266. doi: 10.1111/acem.13345. Epub 2017 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 29125679]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWeber RK. Nasal packing and stenting. GMS current topics in otorhinolaryngology, head and neck surgery. 2009:8():Doc02. doi: 10.3205/cto000054. Epub 2011 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 22073095]

Murer K, Soyka MB. [The treatment of epistaxis]. Praxis. 2015 Sep 2:104(18):953-8. doi: 10.1024/1661-8157/a002112. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26331200]

Beule AG, Weber RK, Kaftan H, Hosemann W. [Review: pathophysiology and methodology of nasal packing]. Laryngo- rhino- otologie. 2004 Aug:83(8):534-51; quiz 553-6 [PubMed PMID: 15316896]

Hull HF, Mann JM, Sands CJ, Gregg SH, Kaufman PW. Toxic shock syndrome related to nasal packing. Archives of otolaryngology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1983 Sep:109(9):624-6 [PubMed PMID: 6882275]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMárquez Moyano JA, Jiménez Luque JM, Sánchez Gutiérrez R, Rodríguez Tembleque L, Ostos Aumente P, Roldán Nogueras J, López Villarejo P. [Toxic shock syndrome associated with nasal packing]. Acta otorrinolaringologica espanola. 2005 Oct:56(8):376-8 [PubMed PMID: 16285438]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence