Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Posterior Abdominal Wall Nerves

Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Posterior Abdominal Wall Nerves

Introduction

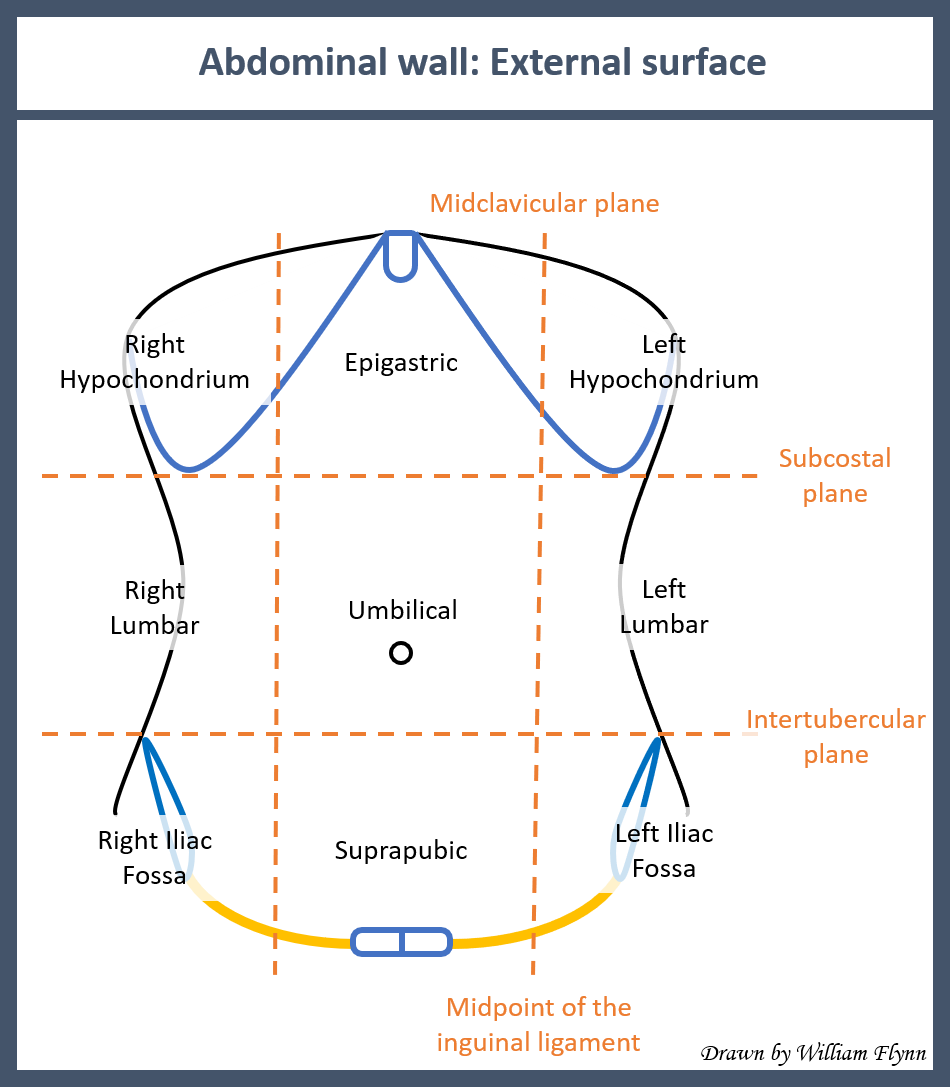

The abdominal cavity is a closed cavity that acts as a protection for all the abdominal viscera. The abdominal wall is a physical barrier that prevents injuries of traumatic or microbial etiology. It acts as a scaffold for the abdominal viscera to affix for proper anatomical and physiological functions, such as increasing intra-abdominal pressure for various normal activities (i.e., defecation, coughing). The abdominal wall can broadly subdivide into anterolateral and posterior segments. See Image. Surface Anatomy of the Abdominal Wall.

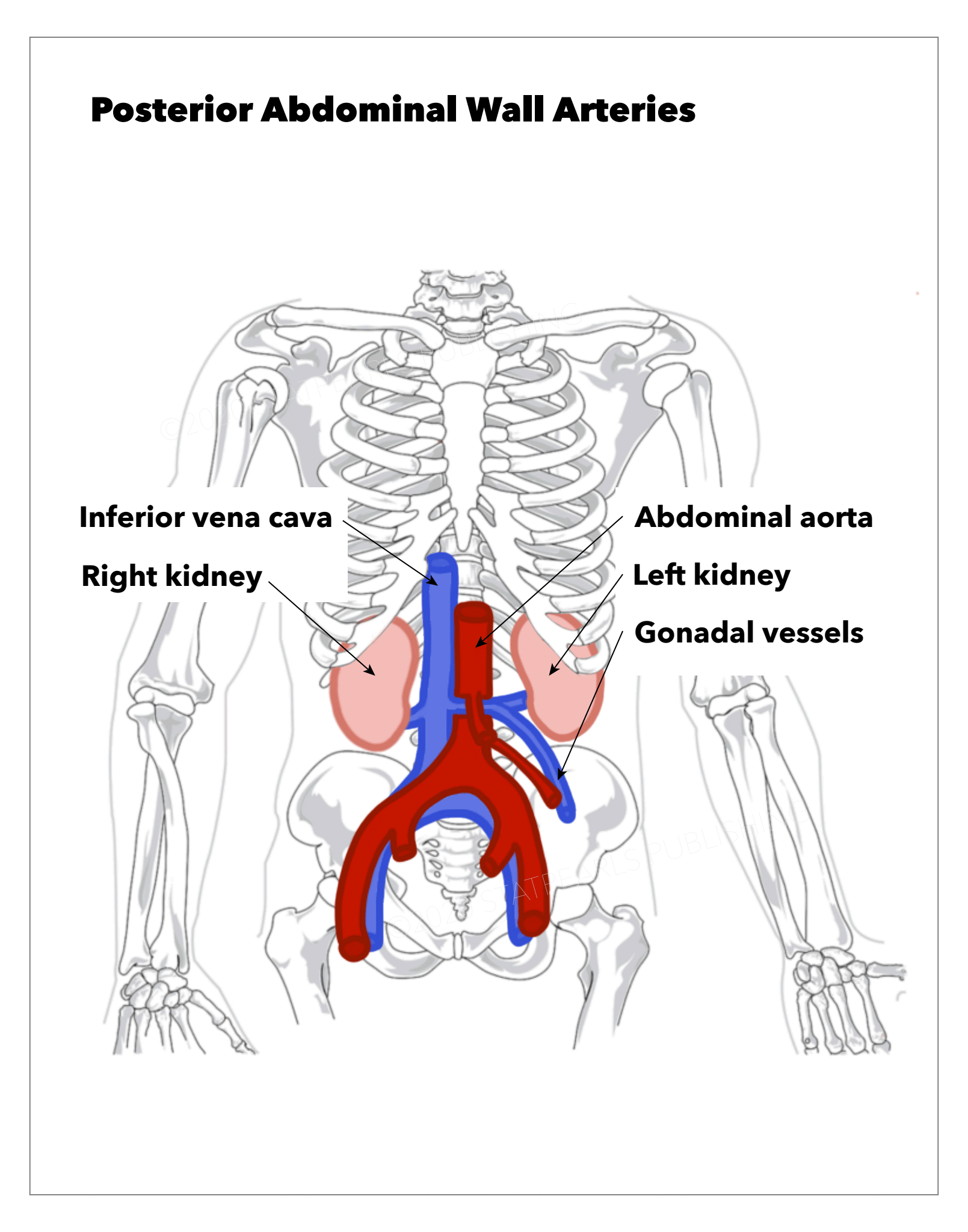

The posterior abdominal wall primarily serves as protection for the retroperitoneal organs (see Image. Posterior Abdominal Wall Arteries). It is mostly muscular contributed by the diaphragm, paraspinal, quadratus lumborum, iliacus, and psoas muscles.

The anterolateral abdominal wall consists of nine layers. From superficial to deep, they are the skin, Camper fascia, Scarpa fascia, external oblique muscle, internal oblique muscle, transversus abdominis muscle, transversalis fascia, extraperitoneal fat, parietal peritoneum. It is important to note that Camper fascia and Scarpa fascia are usually adherent to each other and form part of the subcutaneous tissue. Each muscle has a layer of fascia, known as investing fascia, on the superficial aspect.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Posterior Abdominal Wall:

As previously mentioned, the posterior abdominal wall is necessary for the trunk and postural stability, as well as breathing and lower limb movements. It serves as a protective barrier to the retroperitoneal organs.

There are two fasciae in the posterior abdominal wall: the psoas fascia and thoracolumbar fascia. The thoracolumbar fascia splits into the posterior, middle, and anterior layers. The muscles of the posterior wall are sandwiched between these layers, and the nerves generally course from superomedial to inferolateral in the retroperitoneum.[2] Anterior and middle layers are confined to the smaller lumbar region, but the posterior layer extends all over the back from the neck up to loin.[3]

Nerves

The dermatome map of the abdominal wall follows the distribution of the peripheral nerves. The nerves course from posterior to anterior obliquely similar to that of the ribs. Important dermatome landmarks for the abdominal wall are the umbilicus and inguinal fold, which are related to dermatomes T10 and L1, respectively.

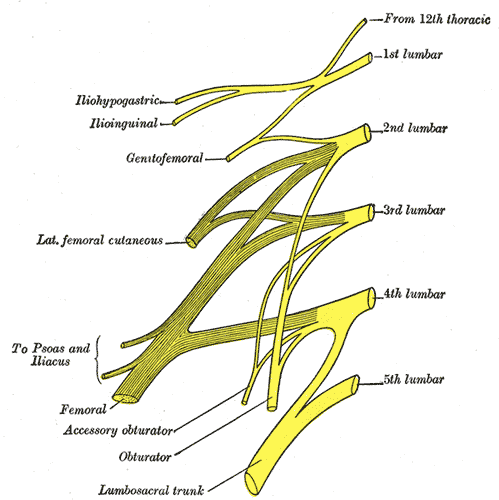

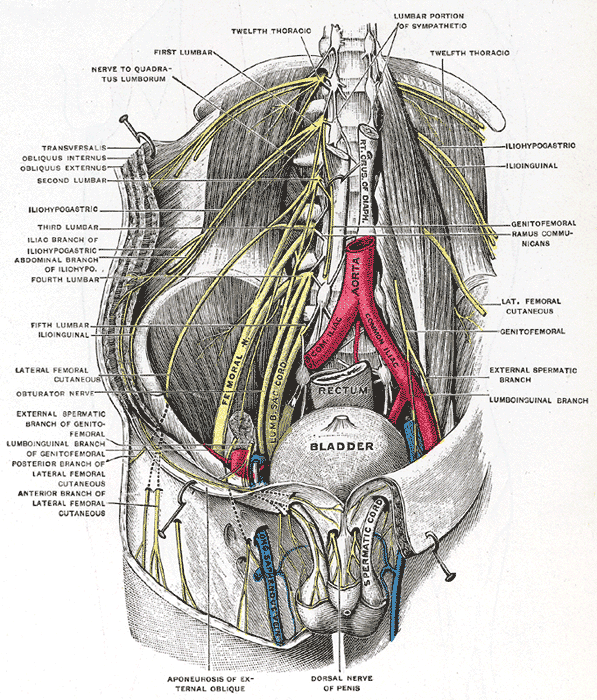

The nerves of the posterior abdominal wall primarily originate from the lumbar plexus (see Image. The Lumbosacral Nerves). The lumbar plexus forms by the ventral rami of the L1-L4 spinal nerves and sometimes includes T12. The plexus gives rise to the following nerves in descending order: iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, lateral femoral cutaneous, obturator, and femoral (see Image. Lumbar Nerves). These nerves and their specific features are discussed below.

Iliohypogastric nerve

- Origin: It is from the ventral primary rami of T12-L1 spinal nerves

- Course: The iliohypogastric nerve emerges from the psoas major and travels between the quadratus lumborum and kidneys to the iliac crest. It later pierces the transversus abdominis and then divides into two cutaneous branches, lateral and anterior.

- Motor innervation: It supplies the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles.

- Sensory innervation: Sensations come from the lateral gluteal region and suprapubic region.

Ilioinguinal nerve

- Origin: This nerve forms from ventral primary rami of L1 [4]

- Course: Similar to the iliohypogastric nerve, the ilioinguinal nerve emerges from the psoas major and courses to the iliac crest to pierce the transversus abdominis. From there, it travels through the deep inguinal ring and into the spermatic cord.

- Motor innervation: It supplies the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles along with the iliohypogastric nerve.

- Sensory innervation: The cutaneous sensation is received from the anteromedial aspect of the thigh, and parts of external genitalia.[5]

Genitofemoral nerve

The genitofemoral nerve is responsible for both sensory and motor components of the cremasteric reflex.

- Origin: Ventral primary rami of L1-L2 spinal nerves

- Course: Travels within the psoas major tissue and emerges on the anterior surface of the psoas, where it then divides into the genital and femoral branches. The genital branch travels within the spermatic cord, and the femoral branch travels to the area of the saphenous opening. [6]

- Motor innervation: This nerve supplies only one muscle known as the cremaster muscle (by its genital branch).

- Sensory innervation: Cutaneous sensation comes from the superomedial aspect of the thigh (femoral branch), or femoral triangle.

Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve

- Origin: Dorsal primary rami of L2-L3 spinal nerves

- Course: Emerges from the lateral border of the psoas major and passes inferolateral across the iliacus muscle, under the inguinal ligament, and then across the sartorius muscle. It then divides into anterior and posterior branches.

- Motor innervation: This nerve has no motor innervation.

- Sensory innervation: The cutaneous sensations are brought from the anterolateral part of the thigh.[7]

Obturator nerve

- Origin: Anterior division of the ventral primary rami of L2-L4 spinal nerves

- Course: Descends through the psoas major and emerges medially near the pelvic brim. It then travels through the obturator canal and divides into anterior and posterior branches.[8] It is the primary nerve supplying the adductor compartment of the thigh.

- Motor innervation: Obturator externus, adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, gracilis, and pectineus.

- Sensory innervation: The cutaneous sensations are brought from the medial part of the thigh by the cutaneous branch of the subsartorial plexus.

- Joints: It supplies both the knee and hip joints.

Femoral nerve

- Origin: Posterior division of ventral rami of L2-L4 spinal nerves. It is the biggest branch of the lumbar plexus

- Course: Travels through the psoas major, adjacent to the iliacus, then below the inguinal ligament. It then courses lateral to the femoral vessels within the femoral triangle and then branches into anterior and posterior divisions.

- Motor innervation: It supplies many muscles, including iliacus, pectineus, sartorius, rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and vastus intermedius.

- Sensory innervation: It gives rise to the medial cutaneous nerve and intermediate cutaneous nerve of the thigh, which supply the anterior and medial aspect of the thigh. It also gives rise to a very long cutaneous nerve, the saphenous nerve.[9][10]

- Joints: It supplies both the hip joint and knee joints. This is clinically important as the hip joint pains are usually referred to as knee joint leading to misdiagnosis by orthopedic surgeons.[11]

Muscles

The posterior abdominal wall is an osseo-musculo-fascial structure made up of the following structures.Bones: 5 lumbar vertebrae, the eleventh and twelfth ribs and the iliac part of the pelvic bones. Muscles: The muscles are mainly five in number. They are

- Psoas major

- Psoas minor

- Iliacus and

- Quadratus lumborum

- Diaphragm

Diaphragm

It is a dome-shaped muscle that serves as a muscular partition between the abdominal and thoracic cavities. The diaphragm shows three openings: the caval hiatus at the T8 level, the esophageal hiatus at the T10 level, and the aortic hiatus at the T12 level. The central tendon is the confluence of the muscle fibers of the diaphragm. It is an aponeurosis that is essential for the proper functioning of the diaphragm. Additional structures of the diaphragm are the left and right crus, which together form the aortic hiatus and ligament of Treitz.

- Origin: Xiphoid process, ribs 7-12, upper lumbar vertebrae.

- Insertion: All fibers converge to the central tendon at its depressed middle part.

- Function: It is the primary muscle of respiration, helping in inhalation (contraction) and expiration (relaxation).

- Innervation: Phrenic nerve (C3-C5).

Quadratus lumborum

The quadratus lumborum is the muscle on which the kidneys lie. It is present between medially psoas muscle and laterally transverse abdominis muscle

- Origin: Posterior border of the iliac crest, transverse process of L5, and iliolumbar ligament.

- Insertion: Transverse process of L1-L5 vertebrae and inferior border of 12th rib.

- Function: Laterally flexes the lumbar vertebrae and stabilizes the 12th rib during respiration.

- Innervation: Subcostal nerve (T12) and lumber intercostal nerves (L1-L4).

Psoas Major Muscle:

- Origin: Bodies and transverse processes of T12-L4 and the intervertebral disc present between them.

- Insertion: Lesser trochanter of femur.

- Function: Hip flexion.

- Innervation: Lumbar plexus nerves (Ventral rami of L1-L3).[12][13]

Psoas Minor Muscle:

It is a long slender muscle, usually seen in only 60% of the population or lesser.[14] When present it is seen lying on Psoas Major

- Origin: T12 and L1 vertebrae and intervertebral disc

- Insertion: Pectineal line of the brim and iliopubic eminence of the pelvic bone.

- Function: Weak flexor of the lumbar vertebral column

- Innervation: Ventral rami of L1

Iliacus Muscle:

- Origin: Upper 2/3 of Iliac fossa

- Insertion: Lesser trochanter of the femur along with psoas muscle and hence called Ilio-psoas muscle.

- Function: Flexes thigh at the hip joint (when the trunk is fixed & vice versa, just like for psoas major)

- Nerve supply: Ventral rami of L2 & L3 (femoral nerve)

Physiologic Variants

The femoral nerve has been found to anomalously split in the pelvis around the psoas quartus or psoas tertius muscles.[15][16]

The ilioinguinal nerve originates from L1 in only 65% of the population. On the other hand, it can arise from T12 and L1 in 14%, from L1 and L2 in 11%, and L2 and L3 in 10% of the population.[2] Ilioinguinal nerve variations can cause ilioinguinal block failures and also present difficulties in interpreting ilioinguinal nerve syndrome.[17]

Surgical Considerations

The lumbar plexus can suffer damage in surgical procedures requiring a lateral approach to the spine. These injuries commonly result in permanent nerve damage. Thus ongoing studies have been performed regarding safe lateral lumbar spine approaches.[18] Bony landmarks help surgeons navigate safer approaches. Landmarks include the midline of lumbar vertebral bodies, iliac crests, and the anterior superior iliac spines (ASIS). A horizontal line running from the right iliac crest to the left is known as the supracristal plane and is also used to set up a safe surgical approach.[19] In some cases, the femoral nerve may split more superiorly in the pelvis around the psoas quartus or psoas tertius, resulting in unforeseen nerve entrapments. So surgeons must be aware of this variant to reduce complications.[15][16]

The ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric nerve blocks are performed regularly to provide analgesia in many surgical procedures of the inguinal region, especially in pediatric patients. Even though it is an easy and safe procedure, it has a high failure rate of up to 25% due to high anatomical variations.[20]

Obturator nerve block is a usual procedure followed in dealing with many conditions like treating chronic hip pain and improve hip spasticity in conditions like cerebral palsy, paraplegia, and multiple sclerosis. It is also used for analgesia in knee surgery and to prevent thigh adduction during resection of bladder tumors.[8]

Clinical Significance

Injuries to nerves of the posterior abdominal wall are diagnosed based on clinical findings that demonstrate hypoesthesia or hyperesthesia along with the distribution of the affected nerve. One of the most common injuries is to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, which results in meralgia parasthetica. This condition is typically a result of nerve compression under the inguinal ligament, and it manifests as tingling and pain to the anterolateral upper thigh. It commonly results from tight clothing or prolonged prone positioning.[21]

Femoral nerve palsy is another type of lumbar plexus injury that can be caused by direct injury, pelvic fracture, increased pressure around the nerve, or from tumor compression. The femoral nerve runs adjacent to the iliacus muscle, so swelling or injury to the iliacus can result in femoral nerve palsy, too. Specifically, the development of an iliacus hematoma in a patient taking anticoagulants has correlated with compression of the femoral nerve resulting in femoral nerve palsy. This condition will present with numbness to the anterior thigh and weakness with hip flexion and knee extension.[22]

Obturator nerve entrapment usually occurs as a result of obturator hernia. The elderly female population has an anatomic disposition for this injury due to the laxity of ligaments, minimal adipose tissue in the obturator canal, and wider obturator canals. This condition will present with decreased sensation to the medial thigh with weakness of the adduction of the thigh.[23]

Ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve damage can occur during gynecologic surgeries, resulting in abdominal muscle weakness and decreased sensation in the groin and suprapubic region.[24]

Injury to the ilioinguinal nerve is also evident in inguinal herniorrhaphy and open appendectomy. In extreme cases, it can lead to radiating pain and burning sensation, which can be annoying. Here the pain and burning are referred to the inguinal region and sometimes to the genitalia based on its sensory distribution.[4] The ilioinguinal nerve entrapment syndrome is a syndrome with a triad characterized by radiating pain to the iliac fossa, altered sensation in its innervation, and a trigger point medial to anterosuperior iliac spine.[25]

Ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and intercostal nerves are potential candidates for transfer to the femoral and gluteal femoral nerves. This procedure has succeeded in restoring some of the motor functions of the hip and knee joints, which patients lost after the spinal cord injuries.[26]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Lumbar Nerves. This illustration depicts the 5 spinal nerves that arise from either side of the spinal cord below the thoracic spinal cord and above the sacral spinal cord.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Lumbosacral Nerves in the Abdominopelvic Cavity. This illustration shows the lumbosacral nerves and their anatomic relationships within the abdominopelvic cavity.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Seeras K, Qasawa RN, Ju R, Prakash S. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Anterolateral Abdominal Wall. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30247850]

Klaassen Z, Marshall E, Tubbs RS, Louis RG Jr, Wartmann CT, Loukas M. Anatomy of the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves with observations of their spinal nerve contributions. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2011 May:24(4):454-61. doi: 10.1002/ca.21098. Epub 2011 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 21509811]

Willard FH, Vleeming A, Schuenke MD, Danneels L, Schleip R. The thoracolumbar fascia: anatomy, function and clinical considerations. Journal of anatomy. 2012 Dec:221(6):507-36. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01511.x. Epub 2012 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 22630613]

Cho HM, Park DS, Kim DH, Nam HS. Diagnosis of Ilioinguinal Nerve Injury Based on Electromyography and Ultrasonography: A Case Report. Annals of rehabilitation medicine. 2017 Aug:41(4):705-708. doi: 10.5535/arm.2017.41.4.705. Epub 2017 Aug 31 [PubMed PMID: 28971057]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWhiteside JL, Barber MD, Walters MD, Falcone T. Anatomy of ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves in relation to trocar placement and low transverse incisions. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2003 Dec:189(6):1574-8; discussion 1578 [PubMed PMID: 14710069]

Iwanaga J, Simonds E, Schumacher M, Kikuta S, Watanabe K, Tubbs RS. Revisiting the genital and femoral branches of the genitofemoral nerve: Suggestion for a more accurate terminology. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2019 Apr:32(3):458-463. doi: 10.1002/ca.23327. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30592097]

Ellis J, Schneider JR, Cloney M, Winfree CJ. Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Nerve Decompression Guided by Preoperative Ultrasound Mapping. Cureus. 2018 Nov 28:10(11):e3652. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3652. Epub 2018 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 30723651]

Yoshida T, Nakamoto T, Kamibayashi T. Ultrasound-Guided Obturator Nerve Block: A Focused Review on Anatomy and Updated Techniques. BioMed research international. 2017:2017():7023750. doi: 10.1155/2017/7023750. Epub 2017 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 28280738]

Clifton W, Nicolas Cruz CF, Dove C, Damon A, Pichelmann M, Nottmeier E. Abdominal wall paresis after posterior spine surgery: An anatomic explanation. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 2019 Nov:186():105551. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2019.105551. Epub 2019 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 31605897]

Jelinek LA, Scharbach S, Kashyap S, Ferguson T. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Anterolateral Abdominal Wall Fascia. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083814]

Dibra FF, Prieto HA, Gray CF, Parvataneni HK. Don't forget the hip! Hip arthritis masquerading as knee pain. Arthroplasty today. 2018 Mar:4(1):118-124. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2017.06.008. Epub 2017 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 29560406]

Sevensma KE, Leavitt L, Pihl KD. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Rectus Sheath. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725838]

Ilahi M, St Lucia K, Ilahi TB. Anatomy, Thorax, Thoracic Duct. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020599]

Dragieva P, Zaharieva M, Kozhuharov Y, Markov K, Stoyanov GS. Psoas Minor Muscle: A Cadaveric Morphometric Study. Cureus. 2018 Apr 8:10(4):e2447. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2447. Epub 2018 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 29888151]

Wong TL, Kikuta S, Iwanaga J, Tubbs RS. A multiply split femoral nerve and psoas quartus muscle. Anatomy & cell biology. 2019 Jun:52(2):208-210. doi: 10.5115/acb.2019.52.2.208. Epub 2019 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 31338239]

Khalid S, Iwanaga J, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. Split Femoral Nerve Due to Psoas Tertius Muscle: A Review with Other Cases of Variant Muscles Traversing the Femoral Nerve. Cureus. 2017 Aug 9:9(8):e1555. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1555. Epub 2017 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 29021927]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNdiaye A, Diop M, Ndoye JM, Ndiaye A, Mané L, Nazarian S, Dia A. Emergence and distribution of the ilioinguinal nerve in the inguinal region: applications to the ilioinguinal anaesthetic block (about 100 dissections). Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2010 Jan:32(1):55-62. doi: 10.1007/s00276-009-0549-0. Epub 2009 Aug 26 [PubMed PMID: 19707710]

Tubbs RI, Gabel B, Jeyamohan S, Moisi M, Chapman JR, Hanscom RD, Loukas M, Oskouian RJ, Tubbs RS. Relationship of the lumbar plexus branches to the lumbar spine: anatomical study with application to lateral approaches. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2017 Jul:17(7):1012-1016. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2017.03.011. Epub 2017 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 28365495]

Tubbs RS, Salter EG, Wellons JC 3rd, Blount JP, Oakes WJ. Anatomical landmarks for the lumbar plexus on the posterior abdominal wall. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2005 Mar:2(3):335-8 [PubMed PMID: 15796359]

van Schoor AN, Boon JM, Bosenberg AT, Abrahams PH, Meiring JH. Anatomical considerations of the pediatric ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric nerve block. Paediatric anaesthesia. 2005 May:15(5):371-7 [PubMed PMID: 15828987]

Cheatham SW, Kolber MJ, Salamh PA. Meralgia paresthetica: a review of the literature. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2013 Dec:8(6):883-93 [PubMed PMID: 24377074]

Nobel W, Marks SC Jr, Kubik S. The anatomical basis for femoral nerve palsy following iliacus hematoma. Journal of neurosurgery. 1980 Apr:52(4):533-40 [PubMed PMID: 6445414]

Gilbert JD, Byard RW. Obturator hernia and the elderly. Forensic science, medicine, and pathology. 2019 Sep:15(3):491-493. doi: 10.1007/s12024-018-0046-z. Epub 2018 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 30397870]

Abdalmageed OS, Bedaiwy MA, Falcone T. Nerve Injuries in Gynecologic Laparoscopy. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2017 Jan 1:24(1):16-27. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2016.09.004. Epub 2016 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 27639546]

Knockaert DC, D'Heygere FG, Bobbaers HJ. Ilioinguinal nerve entrapment: a little-known cause of iliac fossa pain. Postgraduate medical journal. 1989 Sep:65(767):632-5 [PubMed PMID: 2608591]

Toreih AA, Sallam AA, Ibrahim CM, Maaty AI, Hassan MM. Intercostal, ilioinguinal, and iliohypogastric nerve transfers for lower limb reinnervation after spinal cord injury: an anatomical feasibility and experimental study. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2019 Feb 1:30(2):268-278. doi: 10.3171/2018.8.SPINE181. Epub 2018 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 30497147]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence