Introduction

The sural nerve block is a regional anesthetic technique used as an alternative or adjunct to general anesthesia for foot and ankle surgery. Peripheral nerve blockade of the sural nerve is relatively straightforward due to the sural nerve's superficial course near the ankle.[1][2] The technique was first described by McCutcheon in 1965, who reported a 10% failure rate.[3]

Ultrasound-guided sural nerve blockade is a more advanced technique. However, the sural nerve is small and often not visualized. Perivascular approaches may enhance the likelihood of a successful block.

A traditional ankle block consists of peripheral nerve blocks to 4 major nerves of the ankle—the superficial peroneal, deep peroneal, saphenous, and tibial nerves. The inclusion of the sural nerve block depends on the surgical exposure.[4][5][6] However, the provider should include the sural nerve block regardless of the operative location within the foot, as deep sensory nerve block of the lateral foot and ankle (e.g., vibration sensation) is often important for patient comfort.[7]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Proximal to the popliteal crease, the sciatic nerve divides into the tibial nerve and the common peroneal (fibular) nerve. The tibial nerve extends distally, giving rise to the medial sural nerve and posterior tibial nerve, which primarily innervate the posterior leg and the plantar surface of the foot. The medial sural nerve passes between the heads of the gastrocnemius muscle, penetrates the deep fascia to become superficial about midway down the calf, and continues its course posterior to the lateral malleolus and superficial to the extensor retinaculum.[8][9][10]

Notably, the sural nerve is purely sensory, with no motor fibers.[11] While ultrasound visualization is becoming more common, a sural nerve block can also be performed using only anatomic landmarks. At the level of the ankle, the deep nerves are the tibial and deep peroneal (fibular) nerves, while the superficial nerves include the superficial peroneal (fibular), sural, and saphenous nerves. All these nerves are terminal branches of the sciatic nerve, except for the saphenous, which is a sensory branch of the femoral nerve.[12]

Indications

The sural nerve block provides regional anesthesia for surgeries and postoperative pain control in the posterolateral calf and dorsolateral fifth digit.[1][2]

Contraindications

Contraindications for peripheral nerve blockade also apply to the sural nerve block, including patient refusal, allergy to local anesthetics, infection at or near the injection site, systemic infection, malignancy at the needle entry site, and coagulopathy. Additionally, a regional nerve block is not recommended for patients with preexisting neural deficits in the area of the block. Although caution is warranted in patients on anticoagulation therapy, the ankle and lateral leg are considered compressible or "superficial block" sites.

Equipment

The necessary equipment includes:

- Chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone-iodine.

- High-frequency ultrasound probe with sterile probe cover and gel.

- Local anesthetic, typically 1% lidocaine, for superficial numbing.

- Regional block local anesthetic solution

- Bupivacaine (0.5%) or Ropivacaine (0.5%) for postoperative analgesia.

- Lidocaine (2%) or Mepivacaine (1.5%) for a shorter onset time.

- Syringe (10-20 mL) with extension tubing.

- Short bevel block needle (2 inches, 22-gauge).

Personnel

An anesthesiologist trained in regional anesthesia is preferred for this procedure. Additionally, interprofessional healthcare team members, such as nurses with sedation training, can provide valuable assistance during the procedure.

Preparation

A healthcare provider conducts an informed consent process, followed by a pre-procedural pause. The patient is positioned to expose and provide easy access to the lateral aspect of the leg. Sedation may be administered at the provider's discretion. An aseptic technique involves applying 2% chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone-iodine solution to the skin at the injection site. A sterile gel is applied to the ultrasound probe, which is then covered with a sterile probe cover.

Technique or Treatment

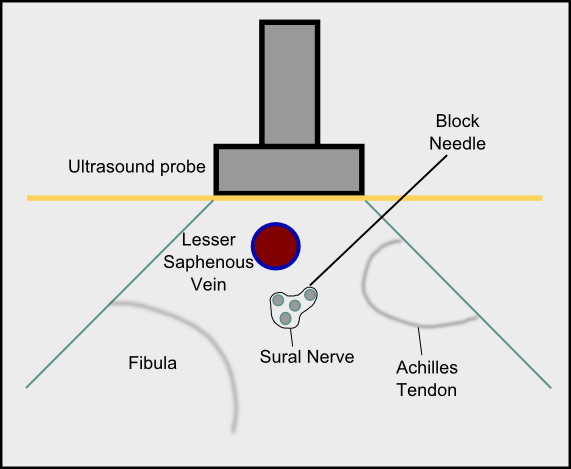

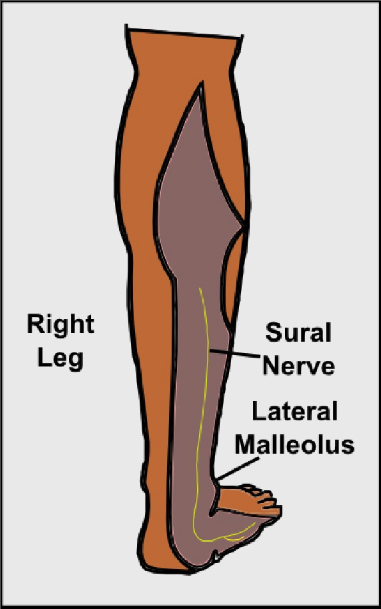

The sural nerve block is typically performed at the level of the ankle. In the ultrasound-guided approach, the provider begins by identifying key anatomical areas, including the posterior border of the lateral malleolus and the Achilles tendon. The injection site, located lateral to the Achilles tendon and posteromedial to the lateral malleolus, is marked (see Image. Sural Nerve in Right Leg). A linear high-frequency ultrasound probe (10-18 MHz) is then placed in a transverse orientation over the marked area, allowing for identification of the small saphenous vein. An out-of-plane approach can be used, with the local anesthetic (typically 5 mL) injected circumferentially around the lesser saphenous vein.[13] Alternatively, an in-plane technique may be used, where the block needle is advanced from posterior to anterior toward the sural nerve (see Image. Sural Nerve Block In-Plane Technique). Applying a calf tourniquet or positioning the leg in a dependent manner may help increase vein size, facilitating easier identification of the sural nerve.

Although ultrasound guidance can reduce the total volume of local anesthetic and minimize the risk of neural or intravascular injection, a standard landmark-based technique remains commonly used. In this traditional approach, the Achilles tendon and lateral malleolus are palpated for identification. The needle is then inserted at the level of the superior border of the lateral malleolus, lateral to the Achilles tendon, with a trajectory directed toward the lateral malleolus. If paresthesia is elicited, needle advancement is halted, and a local anesthetic (approximately 3-5 mL) is injected after confirming a negative aspiration. If paresthesia is not detected, the needle is advanced until it contacts the lateral malleolus bone, and a local anesthetic is then injected after the needle is withdrawn.[3][14][15] In addition to anesthesia in the posterolateral calf and dorsolateral fifth digit, a successful block may also be indicated by loss of sympathetic tone, with color changes and rubor of the foot.

Complications

Although complications are rare, they may include pain during injection, bleeding, infection, and allergic reactions. Intravascular injections can lead to local anesthetic toxicity. Nerve damage and significant pain may occur if the needle tip is subfascicular, perineural, or intraneural.[16]

Clinical Significance

Although the sural nerve innervates the posterolateral calf and dorsolateral foot, it is the least represented among the 5 major nerves of the ankle in scientific literature. A PubMed search using the keywords “sural nerve” and “regional anesthesia” yielded only 6 references. This limited representation may be due to the omission of the sural nerve block in certain foot surgeries, as it contributes minimally to the forefoot. In a study by Coe and Ram, 30 ankle blocks were performed, excluding the sural nerve, and patients undergoing surgery medial to the third toe reported excellent anesthesia in all cases.[17]

The sural nerve block technique uses ultrasound-guided and traditional landmark-based approaches. A prospective randomized study by Redborg et al compared the efficacy of both methods. They found that ultrasound guidance, using the lesser saphenous vein as a reference point, resulted in a more complete and longer-lasting block compared to the traditional landmark approach.[13]

Some discrepancies exist in the literature regarding the amount of local anesthetic needed for a successful sural nerve block. In earlier studies describing this technique, McCutcheon used only 1 to 2 mL of local anesthetic.[3] However, most sources now recommend at least 5 to 7 mL. Caution is advised when using volumes greater than 10 mL due to the risk of vascular occlusion and compartment syndrome.[13][18]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The sural nerve block is typically performed by an anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist; however, the patient must be continuously monitored by an anesthetic nurse throughout the procedure. While the procedure is generally straightforward, inadvertent injection into an artery can occur, occasionally leading to acute, catastrophic outcomes. The nurse must vigilantly monitor the patient’s vital signs, check for any complications, and promptly report any abnormalities to the operative team.

Nerve damage can also lead to paresthesias that may persist for weeks or even months. Therefore, the nurse and operative team should provide thorough patient education, particularly if any complications arise. After the procedure, the recovery room nurse must assess the sensation in the leg before discharge and promptly report any concerns. An interprofessional approach is essential to ensure the best possible outcomes for the patient.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

The interprofessional team of healthcare providers plays critical roles in ensuring the patient's safety and comfort throughout the procedure. Key interventions include:

- Obtaining informed consent.

- Explaining the procedure to the patient.

- Preparing the leg for the procedure.

- Assembling and preparing the instrument tray.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

The interprofessional healthcare team should carry out the following responsibilities:

- They must continuously monitor the patient during the procedure.

- They should ensure resuscitation equipment is readily available in the room before the procedure begins.

Media

References

HUTCHESON JB. Acute lateral ankle sprains treated by sural nerve block. United States Armed Forces medical journal. 1951 May:2(5):799-801 [PubMed PMID: 14836073]

Myerson MS, Ruland CM, Allon SM. Regional anesthesia for foot and ankle surgery. Foot & ankle. 1992 Jun:13(5):282-8 [PubMed PMID: 1624194]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMcCutcheon R. Regional anaesthesia for the foot. Canadian Anaesthetists' Society journal. 1965 Sep:12(5):465-74 [PubMed PMID: 5861276]

Yurgil JL, Hulsopple CD, Leggit JC. Nerve Blocks: Part II. Lower Extremity. American family physician. 2020 Jun 1:101(11):669-679 [PubMed PMID: 32463641]

Nimana KVH, Senevirathne AMDSRU, Pirannavan R, Fernando MPS, Liyanage UA, Salvin KA, Malalasekera AP, Mathangasinghe Y, Anthony DJ. Anatomical landmarks for ankle block. Journal of orthopaedic surgery and research. 2023 Sep 7:18(1):665. doi: 10.1186/s13018-023-04039-2. Epub 2023 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 37674225]

Albaqami MS, Alqarni AA. Efficacy of regional anesthesia using ankle block in ankle and foot surgeries: a systematic review. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2022 Jan:26(2):471-484. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202201_27872. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35113423]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLópez AM, Sala-Blanch X, Magaldi M, Poggio D, Asuncion J, Franco CD. Ultrasound-guided ankle block for forefoot surgery: the contribution of the saphenous nerve. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2012 Sep-Oct:37(5):554-7. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3182611483. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22854395]

Lawrence SJ, Botte MJ. The sural nerve in the foot and ankle: an anatomic study with clinical and surgical implications. Foot & ankle international. 1994 Sep:15(9):490-4 [PubMed PMID: 7820241]

Jackson LJ, Serhal M, Omar IM, Garg A, Michalek J, Serhal A. Sural nerve: imaging anatomy and pathology. The British journal of radiology. 2023 Jan 1:96(1141):20220336. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20220336. Epub 2022 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 36039944]

Ghani Y, Najefi AA, Aljabi Y, Vemulapalli K. Anatomy of the Sural Nerve in the Posterolateral Approach to the Ankle: A Cadaveric Study. The Journal of foot and ankle surgery : official publication of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. 2023 Mar-Apr:62(2):286-290. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2022.08.001. Epub 2022 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 36117053]

Mazzella NL, McMillan AM. Contribution of the sural nerve to postural stability and cutaneous sensation of the lower limb. Foot & ankle international. 2015 Apr:36(4):450-6. doi: 10.1177/1071100714560398. Epub 2014 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 25527006]

Duscher D, Wenny R, Entenfellner J, Weninger P, Hirtler L. Cutaneous innervation of the ankle: an anatomical study showing danger zones for ankle surgery. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2014 May:27(4):653-8. doi: 10.1002/ca.22347. Epub 2013 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 24343871]

Redborg KE, Sites BD, Chinn CD, Gallagher JD, Ball PA, Antonakakis JG, Beach ML. Ultrasound improves the success rate of a sural nerve block at the ankle. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2009 Jan-Feb:34(1):24-8. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181933f09. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19258984]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFalyar CR. Ultrasound-Guided Ankle Blocks: A Review of Current Practices. AANA journal. 2015 Oct:83(5):357-64 [PubMed PMID: 26638458]

Sarrafian SK, Ibrahim IN, Breihan JH. Ankle-foot peripheral nerve block for mid and forefoot surgery. Foot & ankle. 1983 Sep-Oct:4(2):86-90 [PubMed PMID: 6642328]

Greensmith JE, Murray WB. Complications of regional anesthesia. Current opinion in anaesthesiology. 2006 Oct:19(5):531-7 [PubMed PMID: 16960487]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCoe A, Ram S. Ultrasound-guided ankle block for forefoot surgery: is sural nerve block necessary? Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2013 May-Jun:38(3):251. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e31828c6842. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23598729]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNoorpuri BS, Shahane SA, Getty CJ. Acute compartment syndrome following revisional arthroplasty of the forefoot: the dangers of ankle-block. Foot & ankle international. 2000 Aug:21(8):680-2 [PubMed PMID: 10966367]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence