Introduction

DiGeorge Syndrome (DGS) is a combination of signs and symptoms caused by defects in the development of structures derived from the pharyngeal arches during embryogenesis. Features of DGS were first described in 1828 but properly reported by Dr. Angelo DiGeorge in 1965, as a clinical trial that included immunodeficiency, hypoparathyroidism, and congenital heart disease.[1]

DGS is one of several syndromes that has historically grouped under a bigger umbrella called 22q11 deletion syndromes, which include Shprintzen-Goldberg syndrome, velocardiofacial syndrome, Cayler cardiofacial syndrome, Sedlackova syndrome, conotruncal anomaly face syndrome, and DGS. Although the genetic etiology of these syndromes may be the same, varying phenotypes has supported the use of different nomenclature in the past, which has led to confusion in diagnosing patients with DGS, which causes potentially catastrophic delays in diagnosis.[2] Current literature supports the use of the names of these syndromes interchangeably.

Features of DGS include an absent or hypoplastic thymus, cardiac abnormalities, hypocalcemia, and parathyroid hypoplasia (See "History and Physical" below). Perhaps, the most concerning characteristic of DGS is the lack of thymic tissue, because this is the organ responsible for T lymphocyte development. A complete absence of the thymus, though very rare and affecting less than 1% of patients with DGS, is associated with a form of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID). T-cells are a differentiated type of white blood cell specializing in certain immune functions: destroying cells that are infected or malignant, existing as an integral part of the innate immune system by killing viruses (e.g., Killer T-cells), helping B-cells mature to produce immunoglobulins for stronger adaptive immunity (e.g. helper T-cells), etc. The degree of immunodeficiency of patients with DGS can present differently depending on the extent of thymic hypoplasia.

Some patients may have a mild to moderate immune deficiency, and the majority of patients have cardiac anomalies. Other features include palatal, renal, ocular, and gastrointestinal anomalies. Skeletal defects, psychiatric disease, and developmental delay are also of concern. There are different opinions about syndrome-related alterations in cognitive development, and a cognitive decline rather than an early onset intellectual disability is observable.[3] The particularities of the clinical presentation requires observation on an individual basis, with careful evaluation and interprofessional treatment throughout the patient's life.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

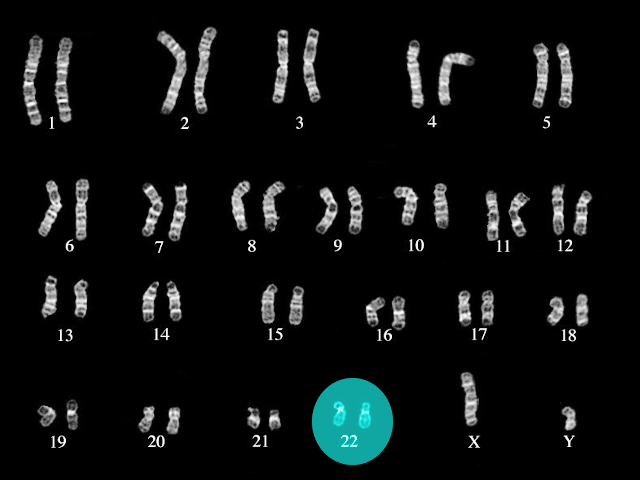

About 90% of DGS cases are a result of a deletion in chromosome 22, more specifically on the long arm (q) at the 11.2 locus (22q11.2). Most of these mutations arise de novo with no genetic abnormalities noted in the genome of the parents of children with DGS.[1] Researchers have identified over 90 different genes at this locus, some of which they have studied in mouse models. The most studied of these genes is T-box transcription factor 1 (TBX1), which correlates with severe defects in the development of the heart, thymus, and parathyroid glands of mouse models. TBX1 also correlates with neuromicrovascular anomalies, which may be responsible for the behavioral and developmental abnormalities seen in DGS.[4][5]

Epidemiology

Microdeletion of 22q11.2 is the most common microdeletion syndrome, affecting approximately 0.1% of fetuses.[6] The rate of 22q11.2 microdeletion in live births occurs at an estimated rate of 1 in 4000 to 6000.[1][7] There are several explanations for the variance in fetal versus live birth prevalence. Firstly, current evidence may not comprise a large enough population. Secondly, 22q11.2 microdeletions may produce embryonically lethal phenotypes, which was observable in animal studies.

The prevalence of 22q11.2 microdeletion may be more common than supported in literature due to several factors. Firstly, not every patient with this microdeletion presents with several craniofacial abnormalities and hence does not undergo genetic testing. African-American children, for example, may not have the craniofacial abnormalities characteristic of DGS in other races. Secondly, access to healthcare, specifically genetic testing, is not available to every individual that might have the microdeletion, regardless of the severity of craniofacial dysmorphism. Further population studies are therefore needed to fully understand the extent and spectrum of 22q11.2 microdeletions in different populations.[8]

Pathophysiology

DGS results from microdeletion of 22q11.2, which encodes over 90 genes. Patients with DGS display a broad array of phenotypes, and the most common findings include cardiac anomalies, hypocalcemia, and hypoplastic thymus.

On a genetic basis, TBX1 has correlations with the most prominent phenotypes characteristic of DGS. Failure in embryologic development of the pharyngeal pouches, which is driven by TBX1, leads to absence or hypoplasia of the thymus and parathyroid glands. Mouse and zebrafish TBX1 knockout models have been studied to understand the embryologic basis of this disease. In mice, for instance, the absence of TBX1 causes severe pharyngeal, cardiac, thymic, and parathyroid defects as well as a behavioral disturbance.[9] Moreover, zebrafish knockouts have demonstrated defects in the thymus and pharyngeal arches as well as malformation of the ears and thymus.[10]

A 22q11.2 knockout mouse model has also been studied, with findings pertinent for molecular and behavioral changes seen in Parkinson's disease, autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and schizophrenia.[11][12] These findings, as well as the neuromicrovascular pathology found in TBX1 knockout mice, suggest a molecular basis for the psychiatric pathologies associated with DGS.[4][5] Of note, individuals affected by this syndrome have a 30-fold increased risk of developing schizophrenia.

History and Physical

A detailed history and physical is vital in the diagnosis and assessment of DiGeorge syndrome. A broad spectrum of disease severity exists, and suspicion of DGS from history and physical can prompt further evaluation. Although most cases get diagnosed in the prenatal and pediatric periods, diagnosis can also occur in adulthood. Delay in motor development is a common presenting feature first recognized by parents who notice delays in rolling over, sitting up, or other infant milestones.[13] These findings can be associated with delayed speech development and learning disabilities. Later in life, abnormal behavior in the setting of poor developmental history may be the chief presenting symptom of DGS.[1]

A detailed history may reveal the following:

- Family history of diagnosed or suspected DGS

- Abnormal genetic testing results of family members

- Delays in the achievement of developmental milestones

- Behavioral disturbance

- Cyanosis, exercise intolerance, or symptoms

- Recurrent infections secondary to T-cell deficiency

- Speech difficulty

- Difficulty feeding and/or failure to thrive

- Muscle spasms, twitching, tetany, seizure

An examination can reveal findings consistent with several features of DGS:

- A complete cardiopulmonary evaluation can reveal murmurs, cyanosis, clubbing, or edema consistent with aortic arch anomalies, conotruncal defects (e.g., tetralogy of Fallot, truncus arteriosus, pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect, transposition of the great vessels, interrupted aortic arch), or tricuspid atresia.

- A craniofacial examination may demonstrate abnormalities such as cleft palate, hypertelorism, ear anomalies, short down slanting palpebral fissures, short philtrum, and hypoplasia of the maxilla or mandible.

- Recurrent sinopulmonary infections due to T cell deficiency as a result of thymic hypoplasia

- Signs of hypocalcemia, including twitching and muscle spasm, may be evident as a result of parathyroid hypoplasia. Chvostek's and Trousseau's signs may be positive.

- Delayed development, unusual behavior, or signs of psychiatric disorders may be observable.

Evaluation

A clinician makes a definitive diagnosis of DGS in individuals with a microdeletion of chromosome 22 at the 22q11.2 locus. Classic evaluations of genetic abnormalities, such as trisomies, including the Giemsa banding technique, are incapable of revealing microdeletions. Microdeletions responsible for DGS are therefore detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA), single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array, comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) microarray, or quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). The availability and cost of these techniques can delay diagnosis, particularly in resource-poor settings.

Patients diagnosed with or suspected of having DGS should undergo extensive evaluation, particularly if life-threatening cardiac or immunologic deficits are present. The following tests should merit consideration:

- Echocardiogram to evaluate conotruncal abnormalities

- Complete blood count with differential

- T and B Lymphocyte subset panels

- Flow cytometry to assess T cell repertoire

- Immunoglobulin levels

- Vaccine titers for evaluation of response to vaccines

- Serum ionized calcium and phosphorus levels

- Parathyroid hormone level

- Chest x-ray for thymic shadow evaluation

- Renal ultrasound for possible renal and genitourinary defects

- Serum creatinine

- TSH

- Testing for growth hormone deficiency

It is important to note that the broad spectrum of disease severity makes the evaluation of DGS particularly challenging. Cases involving significant cardiac, thymic, and craniofacial deficits are more easily recognizable than those lacking severe features. Implementation of advancing genomic studies and facial recognition technology in modern medicine may assist in more effective diagnosis and evaluation of DGS patients.[14]

Treatment / Management

Treatment and management of DGS require intensive interprofessional care:

- Fortunately, many patients with DGS have minor immunodeficiency, with preservation of T cell function despite decreased T cell production. Frequent follow-up with an immunologist experienced in treating primary immunodeficiencies is advisable. Immunodeficiency in neonates with complete DGS (cDGS) requires management with isolation, intravenous IgG, antibiotic prophylaxis, and either thymic or hematopoietic cell transplant (HSCT).

- Immunization, boosters, intravenous immunoglobulin, and antibiotic prophylaxis regimens should revolve around the individual patient's laboratory values. Antibody titer to administered vaccines should be re-evaluated every six to twelve months to determine the necessity of re-vaccination.[15] Controversy exists surrounding the administration of live vaccines, including the MMR, oral polio, and rotavirus vaccines. However, current evidence suggests both safety and efficacy in children older than one year with proven vaccine response, CD8 count greater than 300, and CD4 count greater than 500. Rotavirus vaccination, of note, has been associated with diarrheal illness in patients with SCID and should not be administered to infants with reduced T cell counts.[16]

- Cardiac anomalies, if not diagnosed during the fetal ultrasound, may present shortly after birth as life-threatening cyanotic heart disease. Pediatric cardiothoracic surgery evaluation may be urgently required. Blood products, if necessary, should be irradiated, CMV negative, and leukocyte reduced to prevent transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease. These measures also aim to reduce lung injury, particularly in surgical cases requiring cardiopulmonary bypass.

- Cleft palate cases require evaluation by an otolaryngologist, plastic surgeon, or oral & maxillofacial surgeon with experience in surgical correction of palatal defects. Repair of a cleft palate can improve feeding ability, speech, and reduce the incidence of sinopulmonary infections.

- Hypocalcemia is manageable with calcium and vitamin D supplementation. Recombinant human PTH is an option in DGS patients refractory to standard therapy.

- Autoimmune diseases are common in DGS patients, including immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), rheumatoid arthritis, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, Graves disease, and Hashimoto thyroiditis. DGS patients should be evaluated carefully for autoimmune symptoms regularly.

- Audiologic evaluation is necessary for DGS patients experiencing difficulty with hearing. Children too young to express difficulty with hearing need assessment, particularly with a delay in cognitive and behavioral development.

- Early intervention services are beneficial for children with impaired cognitive and behavioral development.

- Speech therapy is necessary for difficulty with language secondary to craniofacial anomalies and/or cognitive impairment.

- Psychiatric care for DGS patients with depressive and psychotic symptoms is necessary, as diseases like schizophrenia are associated with DGS.[11][12]

- Genetic counseling is a reasonable consideration for parents of a child with DGS who desire more children, as well as for patients with DGS who may want to become parents. If a parent has the same mutation as an affected child, there is a 50% chance a new baby will also have DGS. (B3)

Advanced approaches for the management of children with complete DiGeorge anomaly

In the cDGS featuring no thymus function and bone marrow stem cells can not develop into T cells, children usually die by age 2 years due to severe infections. In this setting, the proposal is to T cell–replete HSCT. Nevertheless, because of the absence of thymus, this strategy can only obtain engraftment of post thymic T cells.[17] A multicenter survey on the outcome of HSCT showed a survival rate of 33% after matched unrelated donors and 60% in the case of matched sibling transplantations.[18] Recently, the FDA approved the thymus transplantation as standard care. This approach focuses on producing naive T cells with a broad T-cell receptor set. The procedure takes place using general anesthesia, and thymus tissue usually gets transplanted into the recipient subject's quadriceps. Studies indicate up to 75% of long-term survival but have described frequent autoimmune sequelae (e.g., autoimmune hemolysis, thyroiditis, thrombocytopenia, enteropathy, and neutropenia) in survivors.[19](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

All patient findings that are part of DiGeorge syndrome can also be present as isolated anomalies in an otherwise normal individual.

The following conditions present with overlapping features:

- Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome - (polydactyly and cleft palate are common findings).

- Oculo-auriculo vertebral (Goldenhar) syndrome (OAVS) - (ear anomalies, heart disease, vertebral defects, and renal anomalies are present). OAVS often demonstrates a sporadic presentation.

- Alagille syndrome - (butterfly vertebrae, congenital heart disease, and posterior embryotoxon are common to both conditions).

- VATER association (heart disease, vertebral, renal, and limb anomalies present in both conditions). VATER association is a diagnosis of exclusion for which an established etiology to date remains unknown.

- CHARGE syndrome - (any combination of congenital heart disease, palatal differences, atresia choanae, coloboma, renal, growth deficiency, ear anomalies/hearing loss, facial palsy, developmental differences, genitourinary anomalies, and immunodeficiency are present in both syndromes).

Genetic consult is essential along with the complete clinical picture to make an accurate diagnosis of DiGeorge syndrome.

Prognosis

Less than 1% of patients with 22q11.2 microdeletion have complete DGS, the most severe subtype of DGS with a very poor prognosis. Without thymic or hematopoietic cell transplantation, these patients die by 12 months of age. Even with a transplant, however, prognosis remains poor. In a study of 50 infants who received a thymic transplant for complete DGS, only 36 survived to two years.[20]

Patients with partial DGS do not have a defined prognosis, as this depends on the severity of the pathologies associated with the disease. While some do not survive infancy due to severe cardiac anomalies, many survive into adulthood. DGS may be vastly underdiagnosed, and many undiagnosed adults with DGS thrive in the community with undetectable congenital anomalies and minor intellectual and/or social impairment. Improvements in genetic diagnostics will hopefully improve understanding of DGS in the future.

Complications

Cardiac and craniofacial anomalies associated with DGS may require surgical repair. As with any surgical procedure, the possibility of complications, including bleeding, infection, and prolonged hospitalization, exists. These risks are particularly dangerous for DGS patients with significant immunocompromise.

Consistent follow-up of patients with DGS is necessary to evaluate for possible complications: severe recurrent infections, autoimmune diseases, and hematologic malignancies.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Parents of children with DGS should receive patient education as it pertains to the severity of their child's condition. Discussion topics may include the following:

- Early signs and symptoms of infection

- Signs of hypocalcemia

- Safe use of medications

- Surgical intervention options

- Immune therapy options

- Genetic counseling

- Speech therapy for feeding or language difficulty

- Developmental milestones and warning signs of developmental delay

- Benefits of early intervention programs

- Signs and symptoms of psychiatric disorders

Pearls and Other Issues

DiGeorge syndrome is easy to remember using the "CATCH-22" mnemonic:

Conotruncal cardiac anomalies

Abnormal facies

Thymic hypoplasia

Cleft palate

Hypocalcemia

22q11.2 microdeletion

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Management of DGS requires an interprofessional approach by a team of healthcare professionals. Obstetricians and genetic counselors can assist in diagnosis and management prenatally. Neonatologists, primary care pediatricians, family medicine physicians, immunologists, cardiothoracic surgeons, pediatricians, craniofacial surgeons, and other medical specialties may be involved in the care of patients with DGS. Collaboration with nurses, pharmacists, psychologists, speech therapists, and other healthcare professionals is paramount. Pharmacists can verify agent selection and dosing with medications to address the endocrine aspects of the disease. Nursing can counsel parents and monitor treatment progress. Psychological professionals can assist with developmental difficulties, as well as work with family members. Patients with DGS require lifelong, consistent follow-up. Because numerous organs are involved, close follow up with each specialist is necessary. Open communication and collaboration between all members of the interprofessional healthcare team are vital to ensure good outcomes. [Level 5]

Diagnosis and management can be challenging, and the interprofessional team can provide a collaborative effort to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with DGS. Current evidence regarding the management of DGS reflects level 5 evidence, and treatment options require a tailored approach around the individual patient's disease manifestations.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

McDonald-McGinn DM, Sullivan KE, Marino B, Philip N, Swillen A, Vorstman JA, Zackai EH, Emanuel BS, Vermeesch JR, Morrow BE, Scambler PJ, Bassett AS. 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Nature reviews. Disease primers. 2015 Nov 19:1():15071. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.71. Epub 2015 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 27189754]

Fomin AB, Pastorino AC, Kim CA, Pereira CA, Carneiro-Sampaio M, Abe-Jacob CM. DiGeorge Syndrome: a not so rare disease. Clinics (Sao Paulo, Brazil). 2010:65(9):865-9 [PubMed PMID: 21049214]

Cascella M, Muzio MR. Early onset intellectual disability in chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Revista chilena de pediatria. 2015 Jul-Aug:86(4):283-6. doi: 10.1016/j.rchipe.2015.06.019. Epub 2015 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 26358864]

Cioffi S, Martucciello S, Fulcoli FG, Bilio M, Ferrentino R, Nusco E, Illingworth E. Tbx1 regulates brain vascularization. Human molecular genetics. 2014 Jan 1:23(1):78-89. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt400. Epub 2013 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 23945394]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePaylor R, Glaser B, Mupo A, Ataliotis P, Spencer C, Sobotka A, Sparks C, Choi CH, Oghalai J, Curran S, Murphy KC, Monks S, Williams N, O'Donovan MC, Owen MJ, Scambler PJ, Lindsay E. Tbx1 haploinsufficiency is linked to behavioral disorders in mice and humans: implications for 22q11 deletion syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006 May 16:103(20):7729-34 [PubMed PMID: 16684884]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGrati FR, Molina Gomes D, Ferreira JC, Dupont C, Alesi V, Gouas L, Horelli-Kuitunen N, Choy KW, García-Herrero S, de la Vega AG, Piotrowski K, Genesio R, Queipo G, Malvestiti B, Hervé B, Benzacken B, Novelli A, Vago P, Piippo K, Leung TY, Maggi F, Quibel T, Tabet AC, Simoni G, Vialard F. Prevalence of recurrent pathogenic microdeletions and microduplications in over 9500 pregnancies. Prenatal diagnosis. 2015 Aug:35(8):801-9. doi: 10.1002/pd.4613. Epub 2015 Jun 24 [PubMed PMID: 25962607]

Botto LD, May K, Fernhoff PM, Correa A, Coleman K, Rasmussen SA, Merritt RK, O'Leary LA, Wong LY, Elixson EM, Mahle WT, Campbell RM. A population-based study of the 22q11.2 deletion: phenotype, incidence, and contribution to major birth defects in the population. Pediatrics. 2003 Jul:112(1 Pt 1):101-7 [PubMed PMID: 12837874]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMcDonald-McGinn DM, Minugh-Purvis N, Kirschner RE, Jawad A, Tonnesen MK, Catanzaro JR, Goldmuntz E, Driscoll D, Larossa D, Emanuel BS, Zackai EH. The 22q11.2 deletion in African-American patients: an underdiagnosed population? American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2005 Apr 30:134(3):242-6 [PubMed PMID: 15754359]

Zhang Z, Huynh T, Baldini A. Mesodermal expression of Tbx1 is necessary and sufficient for pharyngeal arch and cardiac outflow tract development. Development (Cambridge, England). 2006 Sep:133(18):3587-95 [PubMed PMID: 16914493]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuner-Ataman B, González-Rosa JM, Shah HN, Butty VL, Jeffrey S, Abrial M, Boyer LA, Burns CG, Burns CE. Failed Progenitor Specification Underlies the Cardiopharyngeal Phenotypes in a Zebrafish Model of 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. Cell reports. 2018 Jul 31:24(5):1342-1354.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.06.117. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30067987]

Sumitomo A, Horike K, Hirai K, Butcher N, Boot E, Sakurai T, Nucifora FC Jr, Bassett AS, Sawa A, Tomoda T. A mouse model of 22q11.2 deletions: Molecular and behavioral signatures of Parkinson's disease and schizophrenia. Science advances. 2018 Aug:4(8):eaar6637. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aar6637. Epub 2018 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 30116778]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMeechan DW, Maynard TM, Tucker ES, Fernandez A, Karpinski BA, Rothblat LA, LaMantia AS. Modeling a model: Mouse genetics, 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome, and disorders of cortical circuit development. Progress in neurobiology. 2015 Jul:130():1-28. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.03.004. Epub 2015 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 25866365]

McDonald-McGinn DM, Sullivan KE. Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (DiGeorge syndrome/velocardiofacial syndrome). Medicine. 2011 Jan:90(1):1-18. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3182060469. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21200182]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKruszka P, Addissie YA, McGinn DE, Porras AR, Biggs E, Share M, Crowley TB, Chung BH, Mok GT, Mak CC, Muthukumarasamy P, Thong MK, Sirisena ND, Dissanayake VH, Paththinige CS, Prabodha LB, Mishra R, Shotelersuk V, Ekure EN, Sokunbi OJ, Kalu N, Ferreira CR, Duncan JM, Patil SJ, Jones KL, Kaplan JD, Abdul-Rahman OA, Uwineza A, Mutesa L, Moresco A, Obregon MG, Richieri-Costa A, Gil-da-Silva-Lopes VL, Adeyemo AA, Summar M, Zackai EH, McDonald-McGinn DM, Linguraru MG, Muenke M. 22q11.2 deletion syndrome in diverse populations. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2017 Apr:173(4):879-888. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38199. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28328118]

Al-Sukaiti N, Reid B, Lavi S, Al-Zaharani D, Atkinson A, Roifman CM, Grunebaum E. Safety and efficacy of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine in patients with DiGeorge syndrome. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2010 Oct:126(4):868-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.07.018. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20810153]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBakare N, Menschik D, Tiernan R, Hua W, Martin D. Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) and rotavirus vaccination: reports to the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS). Vaccine. 2010 Sep 14:28(40):6609-12. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.039. Epub 2010 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 20674876]

McGhee SA, Lloret MG, Stiehm ER. Immunologic reconstitution in 22q deletion (DiGeorge) syndrome. Immunologic research. 2009:45(1):37-45. doi: 10.1007/s12026-009-8108-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19238335]

Janda A, Sedlacek P, Hönig M, Friedrich W, Champagne M, Matsumoto T, Fischer A, Neven B, Contet A, Bensoussan D, Bordigoni P, Loeb D, Savage W, Jabado N, Bonilla FA, Slatter MA, Davies EG, Gennery AR. Multicenter survey on the outcome of transplantation of hematopoietic cells in patients with the complete form of DiGeorge anomaly. Blood. 2010 Sep 30:116(13):2229-36. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275966. Epub 2010 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 20530285]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDavies EG, Cheung M, Gilmour K, Maimaris J, Curry J, Furmanski A, Sebire N, Halliday N, Mengrelis K, Adams S, Bernatoniene J, Bremner R, Browning M, Devlin B, Erichsen HC, Gaspar HB, Hutchison L, Ip W, Ifversen M, Leahy TR, McCarthy E, Moshous D, Neuling K, Pac M, Papadopol A, Parsley KL, Poliani L, Ricciardelli I, Sansom DM, Voor T, Worth A, Crompton T, Markert ML, Thrasher AJ. Thymus transplantation for complete DiGeorge syndrome: European experience. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2017 Dec:140(6):1660-1670.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.03.020. Epub 2017 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 28400115]

Markert ML, Devlin BH, Chinn IK, McCarthy EA. Thymus transplantation in complete DiGeorge anomaly. Immunologic research. 2009:44(1-3):61-70. doi: 10.1007/s12026-008-8082-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19066739]