Introduction

Needlestick injuries are known to occur frequently in healthcare settings and can be serious. In North America, millions of healthcare workers use needles in their daily work, and hence, the risk of needlestick injuries is always a concern. While the introduction of universal precautions and safety conscious needle designs has led to a decline in needlestick injuries, they continue to be reported, albeit on a much smaller scale than in the past. Awareness of needlestick injuries started to develop soon after the identification of HIV in the early 1980s. However, today the major concern after a needlestick injury is not HIV but hepatitis B or hepatitis C. Guidelines have been established to help healthcare institutions manage needlestick injuries and when to initiate post-exposure HIV prophylaxis. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed a model which helps healthcare professionals know when to start antiretroviral therapy.[1][2][3]

Needlestick injuries are an occupational hazard for millions of healthcare workers. Even though universal guidelines have decreased the risks of needlestick injuries over the past 30 years, these injuries continue to occur, albeit at a much lower rate. Healthcare professionals at the highest risk for needlestick injuries are surgeons, emergency room workers, laboratory room professionals, and nurses. The use of needles is unavoidable in healthcare, and even though every hospital has guidelines on proper handling and disposal of needles and the newest design of safety conscious needles, needlestick injuries continue to occur more often in et al. healthcare professionals like surgeons and emergency room personnel. In most cases, needlestick injuries occur chiefly because of unsafe practices and gross negligence on the part of the healthcare workers. The reality is that most needlestick injuries are preventable by following established procedures.

Needlestick injuries came to the forefront of healthcare after the discovery of the HV in the early 1980s. Since the adoption of universal precautions, the number of needlestick injuries has greatly decreased but continues to occur, but the numbers are low. Today the major threat after a needlestick injury is not HIV but acquiring hepatitis B or hepatitis C.

In the past, the majority of needlestick injuries occurred during resheathing of the needle after the withdrawal of blood from a patient. Even though this practice is now no longer recommended, there are experts in infectious disease who indicate that not resheathing the needle greatly increases the risk of needlestick injuries in house cleaners and porters who are in charge of collecting and disposing of the sharps containers. Over the years, many cases of cleaners and porters being injured by unsheathed needles have been reported. Further, this is more of a concern when healthcare workers ignore policies and discard needles directly into the plastic bags instead of the sharps containers. To prevent these injuries, many healthcare institutions have now adopted unique ways of resheathing needles. For example, in the operating room, there are now established protocols on how the nurse will pass sharp instruments and needles to the surgeon and vice versa. Another method of avoiding needlestick injuries is double gloving.

Factors that increase the risk of exposure to body fluids:

- Failure to adopt universal precautions

- Not following established a protocol of safety

- Performing high-risk procedures that increase the risk of blood exposure such as withdrawing blood, working in the dialysis unit, administering blood

- Using needles and other sharp devices that lack safety features

What Organisms are Involved in Needlestick Injuries?

In reality, almost any microorganism can be transmitted following a needlestick injury, but practically only a handful of organisms are of clinical concern. The most important organisms that can be acquired after a needlestick injury include HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. All these three viruses can be acquired by a percutaneous needlestick or splashing of blood on the mucosal surfaces of the body. While HIV primarily affects the immune system, both hepatitis B and C have a predilection for the liver. Tetanus should always be considered when a needlestick injury has occurred, and the patient's vaccination history must be obtained.[4][5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Cause and Consequence of Disease from Needlestick Injuries

Despite the high number of needle sticks that occur in healthcare settings, the majority of healthcare workers do not develop any infection. Even if the skin is punctured or there is a spill in the mucous membranes, the majority of individuals do not acquire any organisms. There has always been a concern that healthcare workers are at a very high risk of developing disease following a needlestick, but the data do not support this belief. The risk of a healthcare professional for developing any infection depends on the type of needle, the severity of the injury, the type of organism in the patient's blood, and prior vaccination status. Finally, one major determining factor in whether an infection will develop is the availability of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP).[6][7]

HIV

HIV infection is a systemic disorder that primarily suppresses the immune system. Over time, almost every organ in the body is involved leading to a variety of symptoms. The virus has an affinity for the CD4 cells, leaving the body in a state of immunosuppression. This leads to the development of opportunistic infections, cancer, and severe wasting. Many patients will go on to develop AIDs. Luckily today Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) is available, and for those who remain compliant with the medication regimens, death is now a rare occurrence. In fact, most people go on to lead a normal life, but HIV is never cured.

However, after a needlestick injury developing HIV is not common at all. In fact, from 1981 to 2010, there have only been 143 possible cases of HIV that were reported among healthcare professionals. Of these only 57 of the exposed workers seroconverted to HIV. Percutaneous needlestick injury was the known cause in 84% of these cases. Other infections acquired from exposure were 9% by the mucocutaneous route and 4% by both routes.

In the United States, the majority of people who have developed HIV as a result of needlestick injuries have been nurses, laboratory workers, non-surgical physicians, and nonclinical laboratory physicians.

Several prospective studies on healthcare workers who have suffered occupational HIV exposure have been done. The data reveal that the risk of transmission from a single percutaneous needle stick or cut with a scalpel from an HIV-infected individual is about 0.3% or 3 out of every 1000 healthcare workers. However, there are several other studies that indicate that the risk of HIV actuating after a needlestick injury is a lot higher, especially in individuals who have been exposed to a higher quantity of blood and struck with a large-bore needle. Others who are at a higher risk are when they are exposed to patients with high viral titers or those patients who have just seroconverted at the time of the needlestick injury.[7]

Viral Hepatitis

Of the viruses, the most common organism acquired via a needlestick injury is hepatitis B. About 30% to 50% of individuals who do contract hepatitis B may develop jaundice, fever, nausea, and vague abdominal pain. In most individuals, these symptoms will spontaneously subside in 4 to 8 weeks. About 2% to 5% of the individuals will go on to develop chronic infection with hepatitis B. Over a lifetime, there is a 15% risk that these individuals will develop liver cancer or cirrhosis.Over twenty years ago in 1997, data from the CDC National Hepatitis Surveillance revealed that there were nearly 500 healthcare workers who acquired hepatitis B from a needlestick injury. This was a significant decline from the previously high 17,000 new cases diagnosed in 1983. A report done in 2009 reported that there were 1550 hepatitis B cases from occupational exposure, of which only 13 were related to employment in a healthcare field with exposure to blood. This decline has chiefly been attributed to the universal availability of the hepatitis B vaccine and the application of universal precautions. Before the availability of the hepatitis B vaccine, the infection rate from a needlestick ranged from 6% to 30%.

The management of an individual who has acquired hepatitis B following a needlestick injury depends on the recipient’s vaccination status. Today, hepatitis B virus immunoglobulin is available but is not recommended until serological data are obtained. In individuals who have not been vaccinated, hepatitis B immunoglobulin can prevent a full-blown infection. If the person is already infected, the immunoglobulin has been shown to produce a much milder infection. For hepatitis B immunoglobulin to be effective, it needs to be administered within the first 24 hours after exposure. It is used in combination with active immunization.

In Individuals who are not vaccinated and suffer a needlestick injury, the rapid protocol for hepatitis B vaccine is undertaken which involves intramuscular injections at times 0, 1, and 2 months followed by a booster shot at 12 months.[4]Hepatitis C

After a needlestick injury, healthcare professionals are also at risk of acquiring hepatitis C. Unfortunately the exact number of healthcare workers who have developed hepatitis C after a needlestick injury remains unknown, because of lack of follow-up. Some epidemiological studies on healthcare workers who got exposed to hepatitis C following a needlestick reveal an infection incidence of about 1.8%. However, today the actual number of hepatitis C cases has dropped significantly. In 1991, there were over 110,000 cases of hepatitis C reported, but by 1997, the numbers had dropped to 38,000. Today it is estimated that healthcare workers who suffer a needlestick injury and develop hepatitis C make up about 2% to 4% of the total number of hepatitis C cases.

After a needlestick injury, most people do not have symptoms of hepatitis C, or if they do develop symptoms, they are vague and may resemble a flu-like syndrome. Unlike hepatitis B virus, where less than 6% of adults develop a chronic infection, with hepatitis C more than 75% of adults will develop a chronic infection. About three-quarters of patients will develop acute liver disease, and of these, about 20% will go on to develop end-stage liver disease or cirrhosis. About 1% to 5% of them will develop hepatocellular cancer over the next 2 to 3 decades. While there is no post-exposure treatment for hepatitis C, there are some newer drugs that have shown promise in preventing the progression of liver damage and lowering the rates of liver cancer.[8]

Epidemiology

Despite awareness and the introduction of universal precaution guidelines, needlestick injuries continue to occur. The exact number of needlestick injuries that occur is not known because many go unreported. In the operating room, minor needlesticks are not uncommon at all. Rough estimates indicate that in the US alone, there are nearly 600,000 needlestick injuries of which half are not reported. Needlestick injuries not only occur in hospitals but occur in every type of healthcare facility like a clinic, outpatient surgery, day surgery, urgent care center, nursing homes, and cosmetic surgery clinics.

Needlestick injuries do not occur with the same frequency in all healthcare workers. The majority of needlestick injuries occur in nurses, surgeons, emergency medical technicians, surgery technologists, and laboratory personnel. In addition, housekeeping personnel and those who clean the sharp boxes are also at high risk for needlestick injuries.[9][10][11]

Impact of Safety Devices on Needle Stick Injuries

Special safety engineered devices (SEDs) have been marketed widely in an effort to reduce the incidence of needlestick injuries. Contrary to an expected drop in needle sticks with greater use of SEDs, studies suggest that the incidence of needle sticks may have increased. Per one study published in the Netherlands in 2018, the needle stick rate prior to implementation of SEDs was 1.9 per 100 healthcare workers. After SED deployment, the incidence of needle stick injuries increased to 2.2 per 100 healthcare workers. The most common causes reported for needle sticks in the study were difficulties in operating the safety device and continued improper disposal of needles. [12]

History and Physical

History

- All previous immunizations and booster shots

- Any body piercings and when they were done

- Any history of hemodialysis

- Any prior exposure to bodily fluids and or treatment

- Complete medical history

- History of hepatitis B vaccination

- History of intravenous drug use

- Last tetanus shot

- Prior blood transfusion history

- Risk factors for HIV and viral hepatitis

- Sexual history

- Travel history outside the United States within the past 12 months

Physical

Most individuals with a needlestick injury do not have any obvious physical findings, except for a puncture wound. However, a baseline physical exam of the skin, heart, lung, liver, and lymphadenopathy should be done. This baseline examination should be made to assist in the diagnosis of any future infection.If the patient whose blood was involved in the needlestick injury is still in the hospital, then their blood work should be obtained to rule out the presence of HIV, HBV, and HCV. The injured healthcare worker should also have complete blood work, electrolytes, and baseline liver function studies. In addition, a serological profile of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C should be obtained. A pregnancy test must be done on all women of childbearing age.

The vaccination status of a prior tetanus shot and hepatitis B must be obtained. If the patient has not had a tetanus shot within the past 10 years, a tetanus booster shot must be administered. There is no vaccine against hepatitis C. Once the initial workup is completed, the infectious disease expert should be consulted ASAP to determine the need for post-exposure prophylaxis.

Evaluation

Usually, the only evaluation is a thorough history and physical exam. Rarely, there may be a concern of a foreign body in which case an x-ray, ultrasound, or CT should be considered.[13][14][15]

Laboratory studies include HIV and a hepatitis panel.

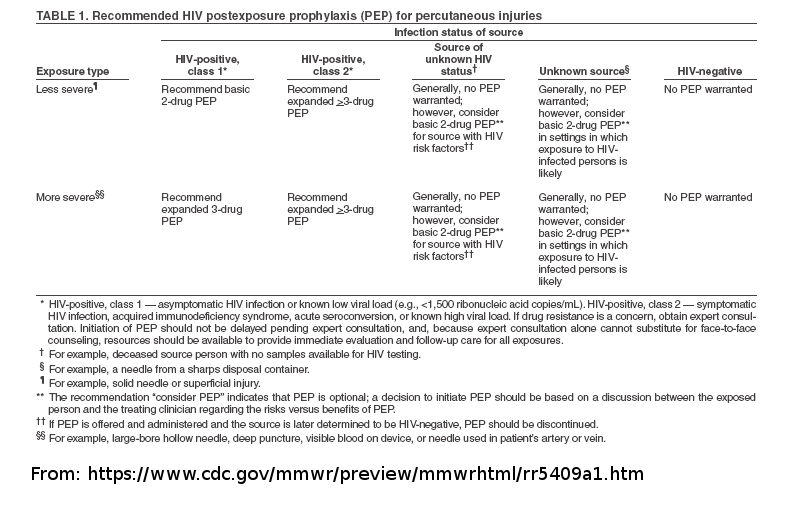

Evaluating for HIV: CDC 3-Step Risk Assessment

The prerequisite for starting PEP for HIV with antiretrovirals is based on evaluating the risk by using the 3-step process developed by the CDC (2014b) and other agencies. 17-20 (Level B) as follows:

Step 1 Determine the Exposure Code: One determines the exposure source which may be blood, bodily fluid or an instrument contaminated with blood (e.g., scalpel). If none, then the risk of HIV transmission is nil. If the answer is yes, then one has to determine the type of exposure:

- If exposure occurred to intact skin, then the risk of acquiring HIV is nil

- If exposure occurred to mucous membranes or in an area of the body where the skin was not intact (e.g., ulcer), one should determine the volume of fluid exposure - a few or large drops and the duration of contact.

- If the exposure was percutaneous, then was it via a superficial abrasion or a solid needle?

- What type of needle was involved? Large bore hollow needle and was it used to obtain blood from the patient’s vein or artery?

Step 2 Status of Patient: it is important to know the HIV status of the patient. If negative, then PEP is not required. If the patient was HIV positive, what was the viral titer (low or high?) and CD4 count. If the HIV status of the patient is unknown, clinical judgment and the patient’s past medical history is necessary to determine the status.

Step 3 Decision on Treatment: Once the above data are collected post-exposure prophylaxis is determined. In general, if the risk of HIV exposure is low, then there is no need for treatment, but the observation is recommended. Individuals at high risk for HIV exposure are offered post-exposure prophylaxis. There are always some cases where the risk may be indeterminate because the patient may not be available for testing. In such cases, one should weigh the benefits of HAART versus the potential adverse effects.

The CDC has a PEP hotline and website available that can help with management decisions.

Visit the Non-Occupational Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (nPEP) Toolkit from the AETC National Coordinating Resource Center

PEP Consultation Service for Clinicians

1-888-448-49119 a.m. – 2 a.m. ETFor more information on the services offered through the PEPline, visit the National Clinicians Consultation Center

Treatment / Management

Hepatitis B Treatment

The following 3 options are available for hepatitis B vaccine in healthcare workers who already have been vaccinated:

- If the patient is HBsAg positive, the recipient’s serology must be assessed. If the post-vaccination anti-HBs level is high (greater than 10 mIU/mL), this is known to be protective, and there is no need for further treatment, and a booster shot is not recommended. However, if the post-vaccination anti-HBs titer is low or if there is no HPV vaccine available, the healthcare worker should be administered hepatitis B immunoglobulin.

- If the patient is HBsAg negative, the healthcare workers should be observed, and his or her anti-HBs levels should be monitored

- If the patient has been discharged or is not available for testing, this requires a significant amount of clinical judgment. Most infectious disease experts treat such cases as if the source was HBsAg negative unless the source has a high risk for HBV infection (such as current or former IV drug use). In this case, the assumption is made that the patient is HBsAg positive, and Post-exposure prophylaxis is initiated (Level B).

If the healthcare worker is not vaccinated against hepatitis B, then these are the following 3 options:

- If the patient is HBsAg positive, the healthcare workers should be administered HBV immunoglobulin immediately, followed by a rapid course of active immunization starting 14 days later.

- If the patient is HBsAg negative, then there is no need to administer hepatitis B immunoglobulin; however, the healthcare worker should strongly be recommended to get the Hepatitis B vaccine.

- If the patient is not available for testing, then the healthcare workers should be managed as if he or she is HBsAg negative. If there is any suspicion about the patient’s clinical status, for example, if the patient had been admitted for a complication of intravenous drug abuse or had risk factors for hepatitis B, then the healthcare workers must be offered Hepatitis B immunoglobulin, and active vaccination should be recommended in 14 days time. According to the CDC, vaccination should be initiated if the exposed person is unvaccinated, and treatment with HBV immunoglobulin should be initiated if the source person is in a high-risk category (Level A).[16][17][18]

HIV Prophylaxis

Today the recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis involve the use of 3-antivirals. The drug treatment should be initiated as soon as possible, preferably within hours of exposure. The duration of treatment is for 4 weeks.

Currently, the CDC recommends using two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) combined with a third drug, which is usually a protease inhibitor. For example, one may combine Tenofovir, emtricitabine plus either dolutegravir or raltegravir. Zidovudine is no longer utilized in this drug regimen because it has not been shown to offer any additional advantage. See CDC guidelines for additional alternate basic regimens and alternate expanded regimens (Prophylaxis and Post Exposure Treatments).

Once a needlestick injury has occurred, the healthcare worker must seek emergency care. The site of the needlestick must be thoroughly rinsed with saline or water, and the wound must be cleaned. In most cases, there is no need to use antiseptic solutions to wash the area. Wound infections usually do not develop within the first 24 hours. Following the injury, there is acute pain, and then most individuals have no other immediate symptoms. However, anxiety, panic, and apprehension are very common because of the fear of contracting a viral infection.

It is important to follow all state, institution, and federal guidelines for reporting all needlestick exposures. There is also a federal law that ensures that all employers of such injuries receive complete medical coverage, including post-exposure prophylaxis and vaccine within a reasonable time at no cost to the employee.[19][20]

Differential Diagnosis

- Rapid HIV testing

- Sexual assault

- Viral hepatitis

- Workers compensation

Prognosis

Once a needle stick injury occurs, all healthcare workers need to follow up with the local Occupational Health and Safety Clinic within 12 to 72 hours. During the workup, the individual must be asked to abstain from sexual intercourse until the HIV testing is negative. In fact, most infectious disease experts recommend safe sex or no sex until the second confirmatory HIV test is also negative, which is usually 4 to 6 months. If the initial workup is negative, then the individual needs to be followed up at 2 and 6 months. For those individuals who develop an infection following a needlestick injury, the prognosis is the same as if they had acquired the organism via any other route.[21][22]

Complications

When an individual is involved in a needlestick injury, it can be a traumatic experience. Even though most individuals never developed any infection, there is always the potential of acquiring a potentially serious infection like HIV or hepatitis C. The healthcare worker has to consult with many consultants and have repeated blood work, which also creates more stress. In many cases, needlestick injuries are not clear-cut, and difficult decisions have to be made on treatment. In addition, the healthcare worker must cope with the fear of not knowing what will happen, since seroconversion with HIV can take months. Plus, the treatment for HIV is not harmless. The use of HAART is associated with a varying number of side effects, most of which are unpleasant. The individual must also deal with family issues and either abstain from sex or use some type of barrier contraception for a long period. Women may have to postpone pregnancy for many months. But the worst part is not knowing the infectious status. Even when there are no symptoms, not knowing is the worst part of a needlestick injury. It should be noted that if PEP is given for only a few days to those of low risk awaiting initial source testing results that there is minimal risk of side effects.

Consultations

Consider consultation with an infectious disease nurse or infectious disease specialist.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Even though most needlestick injuries do not lead to transmission of infection, sometimes one can develop a serious lifelong chronic infection like HIV or hepatitis C. The onus is on the healthcare workers to prevent needlestick injuries in the first place. Experts suggest that no one safety policy can work all the time and thus, one should have an all-inclusive policy that recognizes the behavior of the healthcare workers, institutional policies, and safe use of sharps and other devices. A critical part of any preventive program is to reduce the use of needles whenever possible and utilize other options when available. Hospital workers may also undergo continuous education and training on the newer devices used during dialysis and blood withdrawal. A monitoring program is essential as it can help eliminate potential risk factors that are responsible for needlestick injuries to ensure that the system is working. Today, most hospitals have an infectious disease committee that consists of a nurse, pharmacist, laboratory technologist, physician, and risk management that recommends and introduces safety policies. However, because of the nurse's position, she or he is in a prime position to ensure that the safety rules are being adhered to. The only way to reduce needlestick injuries is by being aware, enforcing the rules, and performing random audits on other healthcare workers. [23][24] [Level 5]

Outcomes

Although many advances have been made in the development of safer needles and sheathing devices, these devices are not fail-safe and only work in settings where the work environment is constantly monitored. Studies, however, do show that the routine use of these needleless systems leads to a marked decrease in needlestick injuries. Today the onus is on healthcare institutions to educate and train their workers on the safer use of sharps and needles. It is necessary for employees to be aware of the consequence of needlestick and what can be done to prevent them. Today most hospitals have instituted policies and protocols to prevent needlestick injuries by advocating the following:

- Establish an occupational health and safety program that primarily monitors and identifies any high-risk procedure and recommended safety maneuvers

- Introduce safe needle use procedures, and use of needleless devices where possible

- Establish the cause of all injuries that occur and how they could have been prevented

- Minimize the use of needles where possible

- Encourage the use of needles with safety features

- Alters any dangerous work practice on the floor and in the operating room

- Provides healthcare professionals with education in needlestick injuries, their prevention, and the current management guidelines

- Promotes a safety culture free of retribution

- Encourage reporting of unsafe practices without fear of reappraisal

- Conducts random audits to ensure that hospital policy and procedures are being followed

- Assesses outcomes periodically

Media

References

Ghanei Gheshlagh R, Aslani M, Shabani F, Dalvand S, Parizad N. Prevalence of needlestick and sharps injuries in the healthcare workers of Iranian hospitals: an updated meta-analysis. Environmental health and preventive medicine. 2018 Sep 7:23(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s12199-018-0734-z. Epub 2018 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 30193569]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVilar-Compte D, de-la-Rosa-Martinez D, Ponce de León S. Vaccination Status and Other Preventive Measures in Medical Schools. Big Needs and Opportunities. Archives of medical research. 2018 May:49(4):255-260. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2018.08.009. Epub 2018 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 30195701]

Joukar F, Mansour-Ghanaei F, Naghipour M, Asgharnezhad M. Needlestick Injuries among Healthcare Workers: Why They Do Not Report their Incidence? Iranian journal of nursing and midwifery research. 2018 Sep-Oct:23(5):382-387. doi: 10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_74_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30186344]

Triassi M, Pennino F. Infectious risk for healthcare workers: evaluation and prevention. Annali di igiene : medicina preventiva e di comunita. 2018 Jul-Aug:30(4 Supple 1):48-51. doi: 10.7416/ai.2018.2234. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30062380]

Oche OM, Umar AS, Gana GJ, Okafoagu NC, Oladigbolu RA. Determinants of appropriate knowledge on human immunodeficiency virus postexposure prophylaxis among professional health-care workers in Sokoto, Nigeria. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2018 Mar-Apr:7(2):340-345. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_32_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30090775]

Dulon M, Wendeler D, Nienhaus A. Seroconversion after needlestick injuries - analyses of statutory accident insurance claims in Germany. GMS hygiene and infection control. 2018:13():Doc05. doi: 10.3205/dgkh000311. Epub 2018 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 30046511]

Pereira MC, Mello FW, Ribeiro DM, Porporatti AL, da Costa S Junior, Flores-Mir C, Gianoni Capenakas S, Dutra KL. Prevalence of reported percutaneous injuries on dentists: A meta-analysis. Journal of dentistry. 2018 Sep:76():9-18. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2018.06.019. Epub 2018 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 29959061]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDemsiss W, Seid A, Fiseha T. Hepatitis B and C: Seroprevalence, knowledge, practice and associated factors among medicine and health science students in Northeast Ethiopia. PloS one. 2018:13(5):e0196539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196539. Epub 2018 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 29763447]

Reddy VK, Lavoie MC, Verbeek JH, Pahwa M. Devices for preventing percutaneous exposure injuries caused by needles in healthcare personnel. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017 Nov 14:11(11):CD009740. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009740.pub3. Epub 2017 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 29190036]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAlhazmi RA, Parker RD, Wen S. Needlestick Injuries Among Emergency Medical Services Providers in Urban and Rural Areas. Journal of community health. 2018 Jun:43(3):518-523. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0446-0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29129032]

Rishi E, Shantha B, Dhami A, Rishi P, Rajapriya HC. Needle stick injuries in a tertiary eye-care hospital: Incidence, management, outcomes, and recommendations. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2017 Oct:65(10):999-1003. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_147_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29044068]

Schuurmans J, Lutgens SP, Groen L, Schneeberger PM. Do safety engineered devices reduce needlestick injuries? The Journal of hospital infection. 2018 Sep:100(1):99-104. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2018.04.026. Epub 2018 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 29738783]

Rawal S, Bogoch II. Evaluation of non-sexual, non-needlestick, non-occupational HIV post-exposure prophylaxis cases. AIDS (London, England). 2017 Jun 19:31(10):1500-1502. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001497. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28574968]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMotaarefi H, Mahmoudi H, Mohammadi E, Hasanpour-Dehkordi A. Factors Associated with Needlestick Injuries in Health Care Occupations: A Systematic Review. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2016 Aug:10(8):IE01-IE04. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/17973.8221. Epub 2016 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 27656466]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFord J, Phillips P. An evaluation of sharp safety intravenous cannula devices. Nursing standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain) : 1987). 2011 Dec 14-2012 Jan 3:26(15-17):42-9 [PubMed PMID: 22324237]

Muller WJ, Chadwick EG. Pediatric Considerations for Postexposure Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prophylaxis. Infectious disease clinics of North America. 2018 Mar:32(1):91-101. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2017.10.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29406979]

Arora G, Hoffman RM. Development of an HIV Postexposure Prophylaxis (PEP) Protocol for Trainees Engaging in Academic Global Health Experiences. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2017 Nov:92(11):1574-1577. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001684. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28445222]

Bamford A, Tudor-Williams G, Foster C. Post-exposure prophylaxis guidelines for children and adolescents potentially exposed to HIV. Archives of disease in childhood. 2017 Jan:102(1):78-83. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309297. Epub 2016 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 27974330]

Stephenson J. Nurses should insist trusts obey sharp safety law. Nursing times. 2016 Feb 24-Mar 1:112(8):2-3 [PubMed PMID: 27071225]

Samaranayake L, Scully C. Needlestick and occupational exposure to infections: a compendium of current guidelines. British dental journal. 2013 Aug:215(4):163-6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.791. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23969653]

Serna-Ojeda JC, Navas A, Graue-Hernandez EO. Smaller needles, lower risks?: Occupational HIV risk for healthcare professionals. HIV medicine. 2017 Sep:18(8):613-614. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12496. Epub 2017 Jan 27 [PubMed PMID: 28127854]

. [HBV post-exposure prevention apparently still effective after 24 hours]. MMW Fortschritte der Medizin. 2015 Nov 19:157(20):6 [PubMed PMID: 26977486]

Adams S, Stojkovic SG, Leveson SH. Needlestick injuries during surgical procedures: a multidisciplinary online study. Occupational medicine (Oxford, England). 2010 Mar:60(2):139-44. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqp175. Epub 2010 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 20064896]

Hatcher IB. Reducing sharps injuries among health care workers: a sharps container quality improvement project. The Joint Commission journal on quality improvement. 2002 Jul:28(7):410-4 [PubMed PMID: 12101553]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence