Introduction

Traumatic injuries of the spleen are either penetrating or blunt. There are grading systems based on severity and anatomy, and management in recent years has become largely nonoperative. Post-splenectomy patients have important immunocompromise issues that must be managed properly in the setting of infection.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Traumatic injuries of the spleen are either penetrating or blunt. In children with splenic trauma, non-accidental trauma must be a consideration. Preexisting splenomegaly makes the spleen capsule weaker and easy to injure, and the inferior portion of the spleen is more caudal and less protected by the ribs. In the United States, most spleen trauma is due to blunt injury, usually from motor vehicle accidents. Less frequently, spleen trauma is penetrating via a variety of mechanisms, either intentional or accidental. In penetrating trauma, the wound can be very small and still cause significant spleen trauma.

Epidemiology

Most references suggest the spleen is the most commonly injured solid organ in trauma for both blunt and penetrating mechanisms. The wound of a penetrating trauma need not be near the spleen to cause significant injury. Penetrating stab wounds made by right-handed assailants tend to enter the abdomen on the left side and are more associated with spleen injuries than if the assailant is left-handed. Other severe injuries can be associated with spleen trauma, so these should be looked for during patient assessment.

Pathophysiology

Spleen trauma is graded from 1 to 5 in increasing order of severity. Grade 1 is less than 10% of surface area involved in hematoma or capsule laceration less than 1 cm. Grade 2 is hematoma 10 to 50% of surface or capsule laceration 1 to 3 cm in depth. Grade 3 is hematoma of more than 50% of the subcapsular surface area or if the hematoma is known to be expanding over time, if the hematoma has ruptured, intraparenchymal hematoma either more than 5 cm or known to be expanding, or capsule laceration more than 3 cm in depth and/or involving a trabecular blood vessel. Grade 4 is a laceration involving a hilar or segmental blood vessel if there is partial devascularization or if it is more than 25% of the spleen. Grade 5 is either a shattered spleen or complete devascularization of the entire spleen. These grades often guide treatment decisions, such as if observational or operative management is chosen for the spleen injury by the treating surgeon. The role of antihemorrhagic intravenous agents such as tranexamic acid is discussed elsewhere.

Toxicokinetics

Pediatric spleen trauma management is similar to that in adults. To reduce potential care delays, the emergency care provider is advised to clarify ahead of time if there are any age cutoffs for trauma patient management in general and spleen injury cases in particular at their specific facility. Antipneumococcal vaccination is typically given around 2 to 3 weeks after splenectomy to decrease the risk of catastrophic sepsis events. Historically, the most feared organisms in this setting have been Streptococcus, Neisseria meningitis, and Haemophilus influenzae type B. Fortunately, as of the 2010s in the developed world, there are effective vaccines for the latter two, which are usually given to children prior to entering elementary school (H. influenzae) or around age 18 (N. meningitis). Anti-streptococcal vaccination is evolving, and polyvalent vaccines are becoming more used and, over time, have been developed against a wider spectrum of subspecies. As of 2017, a 13-valent anti-streptococcal vaccination has become available in some markets. Infectious disease issues affecting trauma patients in the developing world and of completely unimmunized patients are discussed elsewhere. The vast majority of children in developed nations (as of 2017) receive a series of polyvalent anti-streptococcal vaccinations, but to date, this has not changed the post-splenectomy vaccination recommendation. The persistence of an unimmunized minority in developed nations despite the near-unanimous recommendations of the medical community for the immunization of children will likely prevent changes in this recommendation for the foreseeable future.

History and Physical

A history of trauma to the left upper quadrant should increase suspicion of splenic injury. The patient may exhibit a Kehr sign, a pain in the left shoulder that worsens with inspiration. Abdominal tenderness and peritoneal signs are common presentations and should warrant further assessment. Abdominal wall contusions, hematoma, and/or splenomegaly may be present. An unremarkable physical exam should not exclude splenic injury in a patient with a positive history or symptoms.

Evaluation

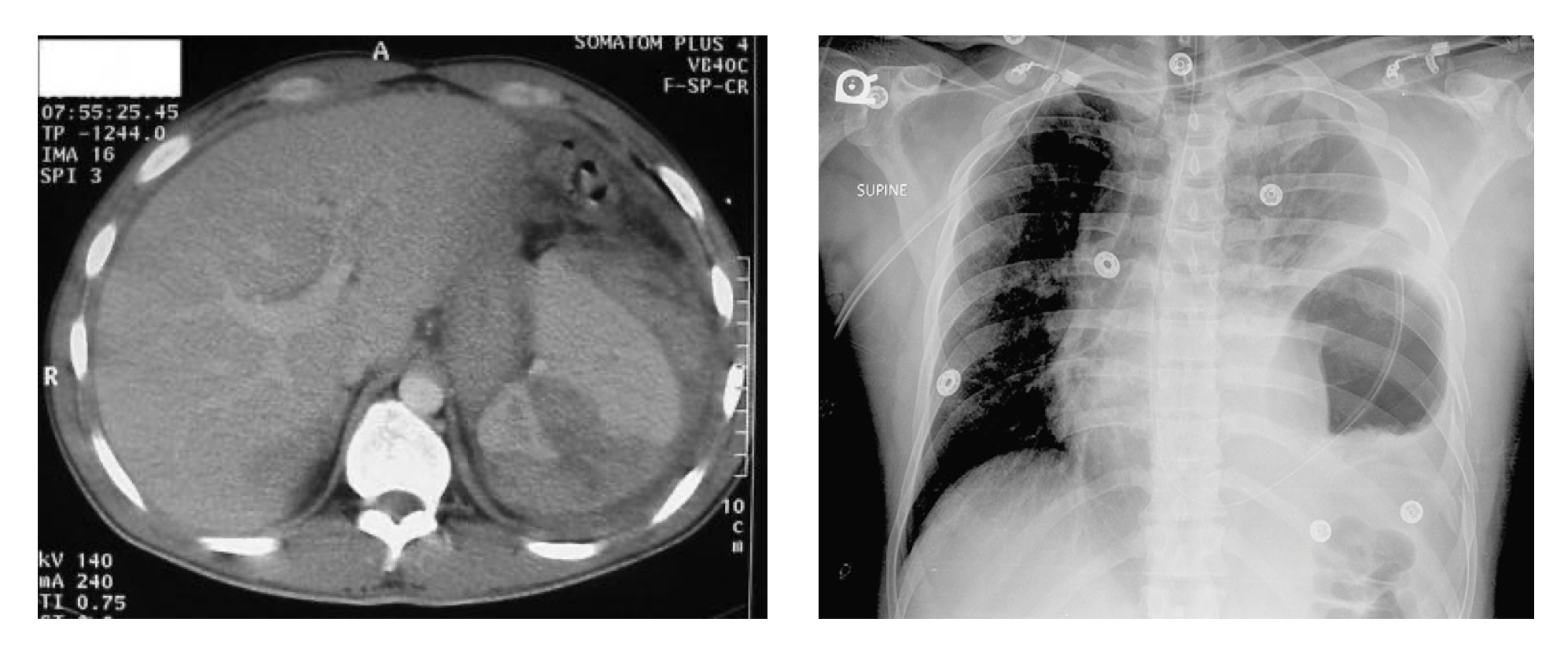

A FAST exam should be used in hemodynamically unstable patients to assess the degree of trauma and bleeding rapidly. It is understood in the developed world that a CT scan will follow a negative FAST evaluation of a trauma patient with a suspicion of intraabdominal trauma unless other operative or management priorities must be addressed first. Where a CT scan is unavailable in a reasonable timeframe, such as in some areas in the developing world or similar settings, diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) can be considered as the next step after negative FAST. CT scan of the abdomen has traditionally been performed with oral and/or intravenous (IV) contrast to assess the degree of injury, although there has been a recent movement toward consideration of ingested contrast as no longer mandatory in the CT scanning of trauma patients with suspected intraabdominal injuries. The IV contrasted spleen is significantly different in appearance on CT than similar images obtained without IV contrast. If IV contrast is not used (as of 2017), it is understood that even with modern multi-detector CT scanning, very significant splenic injuries could be missed by the lack of image optimization. CT findings may include hemoperitoneum, hypodensity, and contrast blush or extravasation. Contrast blush and extravasation are predicted to fail to appear in the absence of adequate IV contrast enhancement of the spleen images. Assessment of vital signs is imperative to monitor hemodynamic status. Repeat CT scans are not indicated in hemodynamically stable patients. Follow-up studies are indicated as needed for patients whose clinical status changes. Plain films and MRI offer limited value and are not indicated for the evaluation of splenic trauma.

Treatment / Management

Management favors nonoperative and conservative treatment in hemodynamically stable patients. Conservative measures include fluid/blood replacement as necessary with monitoring. Patients should be considered for surgical intervention if they are hemodynamically unstable, have a significant injury to other systems, or are currently on anticoagulant/antiplatelet therapy. Candidates for surgical intervention will undergo exploratory laparotomy for assessment, repair, or removal. Angiographic embolization also may be considered as an alternative to surgery in patients who fail nonoperative management.

Differential Diagnosis

Splenic trauma must be discovered in the undifferentiated abdominal trauma patient. The methods of discovery have evolved in the developed world over the last several decades with the advent and subsequent refinement of advanced imaging.[1] A traumatized spleen either requires operative intervention, or it does not. An actively bleeding traumatized spleen is much more likely to require immediate operative intervention by laparotomy than a traumatized spleen where the bleeding remains contained within an otherwise intact splenic capsule. This seems to validate diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) as a method of determining if a splenic trauma patient needs to go to the operating room or could be observed. DPL (discussed in more detail elsewhere) is now of largely historical interest, except in austere environments where advanced imaging is either impossible or prohibitively slow to obtain.[2][3] DPL has also been largely supplanted by point of care ultrasound (POCUS) utilization in the focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST).[4] The specifics of FAST are discussed elsewhere. FAST and its variations follow a rule where an assumption is made that if intraabdominal free fluid can be identified in the undifferentiated abdominal trauma patient, the free fluid is assumed to be hemorrhagic and, therefore, an indication to proceed directly to the operating room for diagnostic and likely therapeutic laparotomy.[5] The reader will note that neither DPL nor FAST is capable of declaring the origin of the bleeding in question; the source of bleeding is to be determined by the operating surgeon at the time of laparotomy in this evaluation model. A FAST exam, if negative, predicts that from an abdominal standpoint, there is sufficient stability to undergo advanced imaging with computed tomography (CT) scanning. This is thought to be much more accurate regarding spleen trauma if intravenous contrast is used. The CT scan images of the traumatized spleen are then used to categorize the injury and predict clinical course and designate the best management plan for that specific injury pattern.[1]

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

The non-operative management of splenic trauma has seen recent refinements. There is an ongoing pursuit of spleen salvage, and with interventional radiology embolization availability, higher grade spleen injuries are undergoing salvage rather than laparotomy removal.[6][7]

Prognosis

Time is of the essence in the initial evaluation and management of the patient with splenic trauma. The time to laparotomy or endovascular management of high-grade splenic trauma can influence outcomes, as increased intraabdominal blood loss can be predicted with delay in definitive management in the patient with high-grade splenic trauma with active intraabdominal hemorrhage. Spleen salvage is preferred as the spleen is very important for optimized immune function. Spleen salvage has been suggested to be more likely at major medical centers with a full spectrum of services.[8] However, if a patient's initial presentation to the health care system is in a remote area with limited resources, the nearest available functional operating room staffed by a general surgeon may offer the best outcome, as prolonged transport times can enhance blood loss and degrade predicted outcome. Some authors have suggested that delayed laparotomy may not offer benefit beyond nonoperative management if a very significant delay in definitive management is unavoidable, but this likely needs validation before making assumptions regarding delayed management of spleen trauma in the austere environment [3]. Historically, splenectomy patients were at elevated risk of catastrophic septic events; immunization against S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and N. meningitidis has suppressed the bulk of that risk [9], but vaccination compliance is non-uniform across populations, leading to variations in predicted infectious disease outcomes in splenectomy patients. [9]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Injury prevention in trauma patients, in general, is a focus of trauma care leadership. In developed nations, some authors suggest that there are potential improvements in infrastructure and general population education, which could save many lives.[10][11] As of 2019, there has been increased interest in the United States regarding increased restrictions on firearm ownership as a method of trauma prevention, but this remains a highly politicized, highly emotionally charged topic with often acrimonious debate.[12]

Pearls and Other Issues

Historically, patients with splenic injuries presenting to community hospitals have undergone splenectomy with general surgeons. Some have suggested a pattern of splenectomy rather than salvage being more likely at smaller hospitals than at large trauma centers. It has further been suggested that this may be related to the capacity in the larger centers to provide more intensive around-the-clock scrutiny of the patient, checking for any sign of deterioration as an indication that operative management had at that point become indicated. There is some anecdotal evidence that patients with low-grade splenic injuries are now transferred more frequently to tertiary/trauma centers, given a prediction of enhanced chances of spleen salvage at the larger facility. High-grade spleen injuries causing acute destabilizing blood loss are still thought best served by laparotomy by general surgery at the facility to which they initially present.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The collaboration between surgery and interventional radiology has allowed patients to undergo spleen salvage who once would have been managed by laparotomy and splenectomy. As is noted above, spleen salvage has increasingly been the goal of management in splenic trauma, with a focus on promoting infectious disease outcomes and avoidance of the potential complications of the laparotomy procedure itself, which can occur even if laparotomy is done when indicated and under the best of preoperative circumstances, which is not necessarily always the case during emergency splenectomies. Interprofessional investigations are ongoing regarding which splenic trauma patients are best served by laparotomy, selective embolization by interventional radiology, or simply observing the patient until adequate healing had occurred to allow the return to outpatient management. Emergency department, critical care, and operative nurses are part of the interprofessional team.[13][14][15][16] [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Leppäniemi A. Nonoperative management of solid abdominal organ injuries: From past to present. Scandinavian journal of surgery : SJS : official organ for the Finnish Surgical Society and the Scandinavian Surgical Society. 2019 Jun:108(2):95-100. doi: 10.1177/1457496919833220. Epub 2019 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 30832550]

Maron S, Baker MS. Splenic rupture due to extraperitoneal gunshot wound: use of peritoneal lavage in the low-tech environment. Military medicine. 1994 Mar:159(3):249-50 [PubMed PMID: 8041476]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMitchell TA, Wallum TE, Becker TE, Aden JK, Bailey JA, Blackbourne LH, White CE. Nonoperative management of splenic injury in combat: 2002-2012. Military medicine. 2015 Mar:180(3 Suppl):29-32. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00411. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25747627]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFeliciano DV. Abdominal Trauma Revisited. The American surgeon. 2017 Nov 1:83(11):1193-1202 [PubMed PMID: 29183519]

McGaha P 2nd, Motghare P, Sarwar Z, Garcia NM, Lawson KA, Bhatia A, Langlais CS, Linnaus ME, Maxson RT, Eubanks JW 3rd, Alder AC, Tuggle D, Ponsky TA, Leys CW, Ostlie DJ, St Peter SD, Notrica DM, Letton RW. Negative Focused Abdominal Sonography for Trauma examination predicts successful nonoperative management in pediatric solid organ injury: A prospective Arizona-Texas-Oklahoma-Memphis-Arkansas + Consortium study. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2019 Jan:86(1):86-91. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002074. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30575684]

Abbas Q, Jamil MT, Haque A, Sayani R. Use of Interventional Radiology in Critically Injured Children Admitted in a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit of a Developing Country. Cureus. 2019 Jan 19:11(1):e3922. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3922. Epub 2019 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 30931193]

Gates RL, Price M, Cameron DB, Somme S, Ricca R, Oyetunji TA, Guner YS, Gosain A, Baird R, Lal DR, Jancelewicz T, Shelton J, Diefenbach KA, Grabowski J, Kawaguchi A, Dasgupta R, Downard C, Goldin A, Petty JK, Stylianos S, Williams R. Non-operative management of solid organ injuries in children: An American Pediatric Surgical Association Outcomes and Evidence Based Practice Committee systematic review. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2019 Aug:54(8):1519-1526. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.01.012. Epub 2019 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 30773395]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCinquantini F, Simonini E, Di Saverio S, Cecchelli C, Kwan SH, Ponti F, Coniglio C, Tugnoli G, Torricelli P. Non-surgical Management of Blunt Splenic Trauma: A Comparative Analysis of Non-operative Management and Splenic Artery Embolization-Experience from a European Trauma Center. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. 2018 Sep:41(9):1324-1332. doi: 10.1007/s00270-018-1953-9. Epub 2018 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 29671059]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBelli AK, Dönmez C, Özcan Ö, Dere Ö, Dirgen Çaylak S, Dinç Elibol F, Yazkan C, Yılmaz N, Nazlı O. Adherence to vaccination recommendations after traumatic splenic injury. Ulusal travma ve acil cerrahi dergisi = Turkish journal of trauma & emergency surgery : TJTES. 2018 Jul:24(4):337-342. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2017.84584. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30028492]

Boyle TA, Rao KA, Horkan DB, Bandeian ML, Sola JE, Karcutskie CA, Allen C, Perez EA, Lineen EB, Hogan AR, Neville HL. Analysis of water sports injuries admitted to a pediatric trauma center: a 13 year experience. Pediatric surgery international. 2018 Nov:34(11):1189-1193. doi: 10.1007/s00383-018-4336-z. Epub 2018 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 30105495]

Asuquo ME, Etiuma AU, Bassey OO, Ugare G, Ngim O, Agbor C, Ikpeme A, Ndifon W. A Prospective Study of Blunt Abdominal Trauma at the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. European journal of trauma and emergency surgery : official publication of the European Trauma Society. 2010 Apr:36(2):164-8. doi: 10.1007/s00068-009-9104-2. Epub 2009 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 26815692]

Madhavan S, Taylor JS, Chandler JM, Staudenmayer KL, Chao SD. Firearm Legislation Stringency and Firearm-Related Fatalities among Children in the US. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2019 Aug:229(2):150-157. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2019.02.055. Epub 2019 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 30928667]

Cunningham AJ, Lofberg KM, Krishnaswami S, Butler MW, Azarow KS, Hamilton NA, Fialkowski EA, Bilyeu P, Ohm E, Burns EC, Hendrickson M, Krishnan P, Gingalewski C, Jafri MA. Minimizing variance in Care of Pediatric Blunt Solid Organ Injury through Utilization of a hemodynamic-driven protocol: a multi-institution study. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2017 Dec:52(12):2026-2030. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.08.035. Epub 2017 Sep 4 [PubMed PMID: 28941929]

Ruscelli P, Buccoliero F, Mazzocato S, Belfiori G, Rabuini C, Sperti P, Rimini M. Blunt hepatic and splenic trauma. A single Center experience using a multidisciplinary protocol. Annali italiani di chirurgia. 2017:88():. pii: S0003469X17026483. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28604373]

Coccolini F, Montori G, Catena F, Kluger Y, Biffl W, Moore EE, Reva V, Bing C, Bala M, Fugazzola P, Bahouth H, Marzi I, Velmahos G, Ivatury R, Soreide K, Horer T, Ten Broek R, Pereira BM, Fraga GP, Inaba K, Kashuk J, Parry N, Masiakos PT, Mylonas KS, Kirkpatrick A, Abu-Zidan F, Gomes CA, Benatti SV, Naidoo N, Salvetti F, Maccatrozzo S, Agnoletti V, Gamberini E, Solaini L, Costanzo A, Celotti A, Tomasoni M, Khokha V, Arvieux C, Napolitano L, Handolin L, Pisano M, Magnone S, Spain DA, de Moya M, Davis KA, De Angelis N, Leppaniemi A, Ferrada P, Latifi R, Navarro DC, Otomo Y, Coimbra R, Maier RV, Moore F, Rizoli S, Sakakushev B, Galante JM, Chiara O, Cimbanassi S, Mefire AC, Weber D, Ceresoli M, Peitzman AB, Wehlie L, Sartelli M, Di Saverio S, Ansaloni L. Splenic trauma: WSES classification and guidelines for adult and pediatric patients. World journal of emergency surgery : WJES. 2017:12():40. doi: 10.1186/s13017-017-0151-4. Epub 2017 Aug 18 [PubMed PMID: 28828034]

Tugnoli G, Bianchi E, Biscardi A, Coniglio C, Isceri S, Simonetti L, Gordini G, Di Saverio S. Nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury in adults: there is (still) a long way to go. The results of the Bologna-Maggiore Hospital trauma center experience and development of a clinical algorithm. Surgery today. 2015 Oct:45(10):1210-7. doi: 10.1007/s00595-014-1084-0. Epub 2014 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 25476466]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence