Mohs Micrographic Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria (AUC) Guidelines

Mohs Micrographic Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria (AUC) Guidelines

Definition/Introduction

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), named after Dr. Frederic Mohs, is a specialized tissue-sparing surgical technique for treating certain types of skin cancer. This procedure is renowned for its effectiveness in completely removing cancerous tissue while preserving as much healthy skin as possible. The surgeon performing this procedure can take little to no margin when removing cancer due to tissue mapping and full-margin analysis with a frozen section. Mohs surgery is particularly advantageous for skin cancers with indistinct clinical borders or those in critical areas, such as the face, where tissue preservation is crucial for cosmetic and functional reasons.[1]

Due to increases in both skin cancer prevalence and the number of physicians trained in MMS, this method has been gaining popularity. From 1995 to 2009, it was estimated that the use of Mohs micrographic surgery increased by 400%.[2] As with any medical procedure, the appropriate use of MMS is guided by specific criteria to ensure its application in situations where its benefits are most pronounced. In 2012, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD), American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS), American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association (ASDS), and American Society for Mohs Surgery (ASMS) collaborated to establish appropriate use criteria for 270 clinical scenarios for which MMS may be considered. In this study, 161 articles were identified, and an Ad Hoc Task Force completed the development of clinical indications for MMS. These indications were then rated for appropriateness for MMS by a panel of 8 Mohs surgeons and 9 non-Mohs dermatologists from varying backgrounds and practice settings. The ratings given were 1 to 3 (inappropriate), 4 to 6 (uncertain), and 7 to 9 (appropriate).[3]

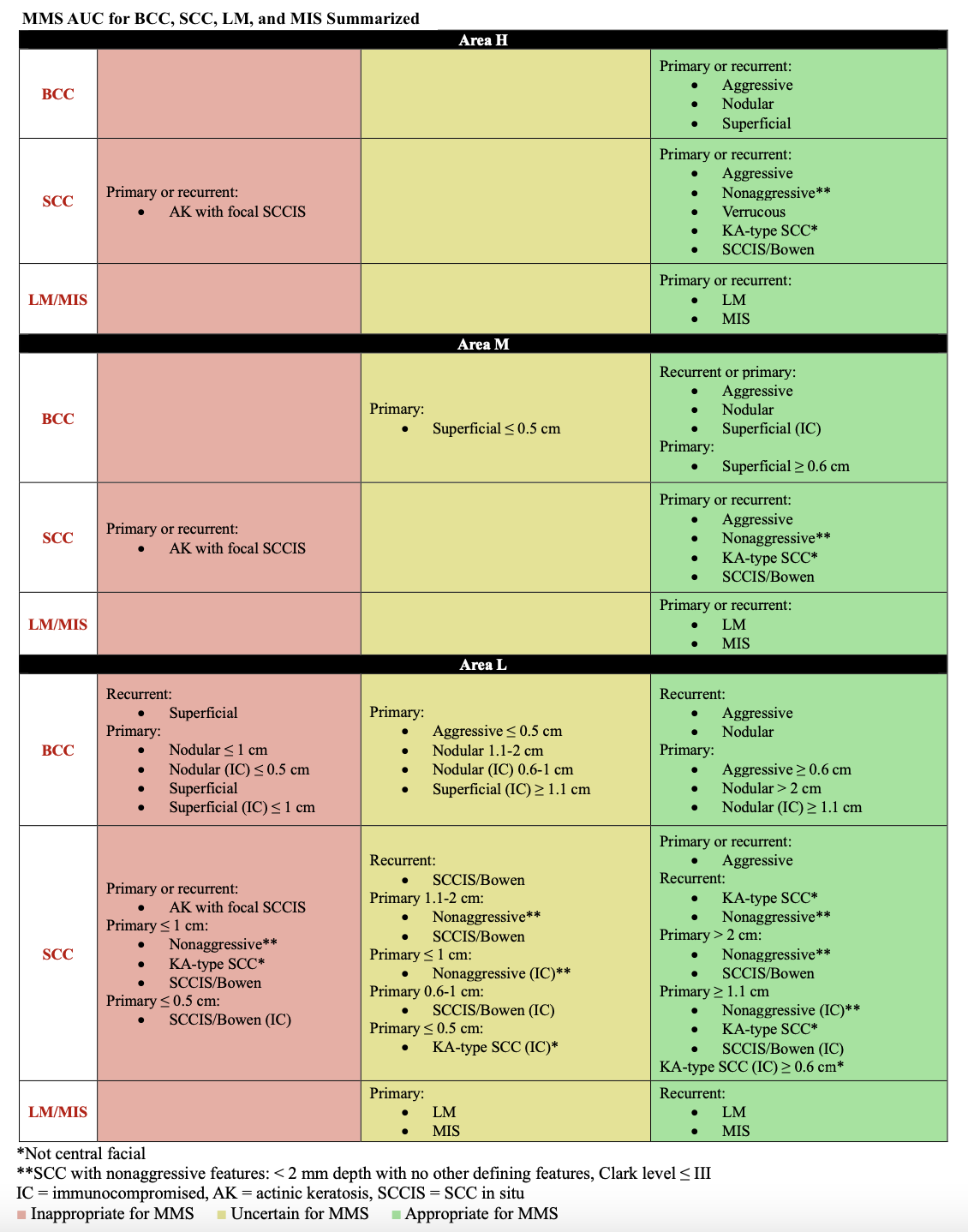

Cancer scenarios evaluated included 69 basal cell carcinomas (BCC), 143 squamous cell carcinomas (SCC), 12 lentigo maligna (LM)/melanoma in situ (MIS), and 46 other rare cutaneous malignancies. Ratings given to each scenario depended on several factors, including area of the body, immune status, genetic syndromes, prior radiation, positive margins, aggressive features, and recurrence.[3]

Results of the 2012 MMS AUC study for BCC, SCC, LM, and MIS are summarized and are organized by type of skin cancer as well as area of the body (see Table. Summary of Mohs microsurgery AUC for Basal Cell Carcinoma, Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Lentigo Maligna, and Melanoma in situ). Area H represents central face, eyelids, eyebrows, nose, lips, chin, ear, periauricular skin/sulci, temples, genitalia, hands, feet, nail units, ankles, and the nipples/areola. Area M includes cheeks, forehead, scalp, neck, jawline, and pretibial surface. Area L includes the trunk and extremities (other than pretibial, acral areas, nail units, and ankles).[3] Boxes shaded green indicate “appropriate,” whereas yellow and red signify “uncertain” and “inappropriate,” respectively. Of the 270 evaluated scenarios, 74.07% were deemed appropriate, 8.89% uncertain, and 17.04% inappropriate.[3]

In addition to the results displayed in the table, the AUC indicates that MMS is also appropriate for sebaceous carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, leiomyosarcoma, extramammary Paget disease (EMPD), dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP), atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), apocrine/eccrine carcinoma, adnexal carcinoma, and adenocystic carcinoma, in all patient types and locations. For Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC), MMS is considered appropriate in areas H and M and uncertain in area L. MMS was also determined to be uncertain for desmoplastic trichoepithelioma in areas H and M, as well as angiosarcoma in all locations. MMS is inappropriate for desmoplastic trichoepithelioma in area L and Bowenoid papulosis in area H.[3]

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

Concerns have been raised regarding the MMS AUC, particularly in the context of superficial basal cell carcinomas (sBCC). Steinman et al argue that many superficial BCCs scored as "appropriate" for Mohs surgery may be more appropriately categorized as "uncertain" or "inappropriate." This contention stems from primary superficial BCCs often exhibiting comparable cure rates when treated with alternative methods such as curettage and cryosurgery. Additionally, superficial BCCs are frequently multifocal, requiring more stages than other BCC types. The limited data on the risk for recurrence and invasion in sBCC cases further complicates the application of AUC.[4] Some challenge this push for reclassification of sBCC, asserting that many biopsied sBCCs may have evidence of more aggressive BCC subtypes on deeper sections, making MMS a useful treatment modality. In addition, it is mentioned that the need for more required stages for sBCC makes these tumors more well-suited to MMS. Finally, it is stated that appropriateness should not be misconstrued as a necessity. Although MMS may be appropriate for an sBCC, this does not negate the fact that other treatment modalities may also be appropriate.[5] The AUC represents minimal requirements and should not be used as a reason to perform MMS on every "appropriate" lesion.[6] Skepticism extends to the geographical scope of the published AUC, as it solely considers publications from the United States, neglecting significant European trials.[7] Critiques also highlight the reliance on expert opinions rather than concrete evidence in determining AUC ratings.[7]

While certain deviations from the AUC are accepted in specific scenarios, such as patient age or ill-defined margins, some authors underscore additional deviations practiced by Mohs surgeons, emphasizing the importance of clinical judgment. These authors identified that common reasons for performing MMS on "uncertain" or "inappropriate" tumors include multiple MMS procedures on the same day, lower leg lesions, and granulation into the adjacent wound.[8] Another study of 1,000 MMS patients revealed that the most common reason for performing MMS on "inappropriate" tumors was the treatment of an additional adjacent lesion in the same session.[9] Finally, certain discrepancies have been identified in the AUC. Specifically, a primary SCC in situ ≥ 2 cm in area L in a healthy patient is classified as "uncertain"; this classification appears to be counterintuitive. In addition, a primary sBCC in "area L" of any size in a patient with a genetic syndrome is classified as "appropriate", while a recurrent sBCC in "area L" of any size in the same patient is classified as "inappropriate".[10] These discrepancies and criticisms of the AUC may warrant further revision and reclassification of certain aspects of the AUC.

Over the past decade, there has been increasing concern regarding the overutilization of MMS and its financial implications due to the associated cost. Some argue that the Mohs AUC fuels increased utilization of MMS. Others emphasize that the AUC was established to identify tumors that are not appropriate for MMS, thereby minimizing inappropriate use.[11][12] A study of trends in MMS from 1995 to 2010 demonstrates that although the use of MMS is increasing, only about 10% of cutaneous malignancies are managed with this technique.[13] In addition, some argue that increased utilization is not the same as overutilization and that the former may be attributed to the increase in skin cancer diagnosis and increased access to MMS rather than the AUC.[14]

Finally, it is important to remember that while the AUC establishes a score of MMS appropriateness for each scenario, it does not specify which other treatment modality may be most appropriate for each clinical scenario. This is because the choice of treatment is ultimately dependent on the practicing physician's clinical expertise as well as patient preferences. MMS being "appropriate" for a given scenario does not necessarily mean it is the best treatment for that patient.[15]

Clinical Significance

Mohs AUC plays a pivotal role in guiding the judicious application of Mohs micrographic surgery and ensuring its clinical significance in dermatological oncology. The AUC, established to categorize cases by appropriateness for Mohs surgery, is instrumental in optimizing patient outcomes, resource utilization, and healthcare efficiency.

One of the primary clinical significances of Mohs AUC lies in patient selection. By systematically evaluating factors such as tumor type, size, location, and recurrence risk, the AUC assists healthcare providers in identifying cases where Mohs surgery is most likely to provide maximum benefits. This nuanced approach enables the allocation of this specialized and resource-intensive procedure to scenarios where its advantages in tissue preservation and high cure rates are most pronounced. The "Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria" mobile application, developed by the AAD, is a useful tool for providers to rapidly determine appropriateness regarding the use of MMS for a specific patient. The application allows you to select by cancer type, location, occurrence, and subtype, ultimately providing a median score of 1 to 9.

The AUC also offers a standardized framework for decision-making, fostering consistency in applying Mohs surgery across different clinical settings. This consistency is particularly crucial given the diverse skin cancers and individual patient variations. The AUC's role in minimizing unnecessary procedures is another key clinical significance. Not all skin cancers warrant the meticulous approach of Mohs surgery and the AUC safeguards against overutilization. By categorizing cases as "inappropriate" where alternative treatments may be more suitable, the AUC prevents unnecessary burdens on healthcare resources, reduces costs, and spares patients from undergoing procedures that may not offer additional clinical benefit. Conversely, the AUC also aids providers in categorizing tumors that do warrant Mohs surgery. Higher AUC scores are associated with significantly more stages taken during surgery.[16]

The AUC also contributes to ongoing quality improvement in dermatologic surgery. Through continuous refinement based on emerging evidence and clinical experience, it should evolve to reflect the dynamic landscape of skin cancer management. This adaptability will ensure that Mohs surgery remains a relevant and effective option, incorporating advancements in diagnostic tools, therapeutic modalities, and understanding of skin cancer biology.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Interprofessional collaboration is pivotal in healthcare, particularly in specialties like dermatology.[17] Mohs surgery, a highly effective treatment for skin cancer, requires a coordinated effort among various healthcare professionals to adhere to appropriate use criteria and provide patients with the best possible care and outcomes.

A study done in 2023 assessed ChatGPT's ability to appropriately categorize 22 surgical scenarios as "appropriate," "indeterminate," or "inappropriate" for MMS based on the AUC. The results demonstrated only a 68% congruence of ChatGPT with established Mohs AUC criteria.[18] This further emphasizes the importance of the human element and collaboration by qualified healthcare professionals to evaluate each patient on a case-by-case basis for appropriateness for MMS.

The interprofessional team involved in Mohs surgery may include dermatologists, Mohs surgeons, pathologists, advanced practice professionals, nurses, primary care physicians, and other allied healthcare professionals. Each member brings unique expertise and perspectives, facilitating comprehensive patient care. Dermatologists and Mohs surgeons use their clinical expertise to assess patients and determine the appropriateness of Mohs surgery based on the AUC. Pathologists play a crucial role in interpreting biopsy results and providing accurate diagnoses, which guide treatment decisions. Nurses and other allied healthcare professionals support patient care through pre-operative preparation, assistance during procedures, and post-operative follow-up.

Ethics also play a significant role in interprofessional collaboration, particularly concerning patient-centered care and shared decision-making. Healthcare professionals must prioritize patient well-being and autonomy, ensuring that treatment decisions align with the patient's preferences, values, and goals.[19] In addition, appropriate adherence to the Mohs AUC, combined with the provider's clinical judgment, prevents overutilization or underutilization of MMS.

Continuous education and training are essential components of interprofessional collaboration in Mohs surgery. Healthcare professionals must stay updated on the latest research, guidelines, and advancements in MMS to provide evidence-based care. Regular training sessions, workshops, and case reviews help ensure that team members have the knowledge and skills necessary to effectively adhere to Mohs AUC.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Table: Summary of Mohs Microsurgery AUC for Basal Cell Carcinoma, Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Lentigo Maligna, and Melanoma in Situ.

AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS Task Force; Connolly SM, Baker DR, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(4):531-550. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.06.009.

References

Prickett KA, Ramsey ML. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28722863]

Asgari MM, Olson JM, Alam M. Needs assessment for Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatologic clinics. 2012 Jan:30(1):167-75, x. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2011.08.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22117877]

Ad Hoc Task Force, Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, Fazio MJ, Storrs PA, Vidimos AT, Zalla MJ, Brewer JD, Smith Begolka W, Ratings Panel, Berger TG, Bigby M, Bolognia JL, Brodland DG, Collins S, Cronin TA Jr, Dahl MV, Grant-Kels JM, Hanke CW, Hruza GJ, James WD, Lober CW, McBurney EI, Norton SA, Roenigk RK, Wheeland RG, Wisco OJ. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2012 Oct:67(4):531-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.06.009. Epub 2012 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 22959232]

Steinman HK, Dixon A, Zachary CB. Reevaluating Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria for Primary Superficial Basal Cell Carcinoma. JAMA dermatology. 2018 Jul 1:154(7):755-756. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0111. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29516099]

MacFarlane DF, Perlis C. Mohs Appropriate Use Criteria for Superficial Basal Cell Carcinoma. JAMA dermatology. 2019 Mar 1:155(3):395-396. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5661. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30725085]

Brodell RT. JAAD Game Changers∗: Application of Mohs micrographic surgery appropriate-use criteria to skin cancers at a university health system. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2021 Nov:85(5):1376. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.048. Epub 2021 Apr 21 [PubMed PMID: 33894323]

Kelleners-Smeets NW, Mosterd K. Comment on 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2013 Aug:69(2):317-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.03.040. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23866871]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRuiz ES, Karia PS, Morgan FC, Liang CA, Schmults CD. Multiple Mohs micrographic surgery is the most common reason for divergence from the appropriate use criteria: A single institution retrospective cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2016 Oct:75(4):830-831. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.06.032. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27646739]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStancut E, Melvin OG, Griffin RL, Phillips CB, Huang CC. Institutional Adherence to Current Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria With Reasons for Nonadherence and Recommendations for Future Versions. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2022 Mar 1:48(3):290-292. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000003369. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35025848]

Croley JA, Joseph AK, Wagner RF Jr. Discrepancies in the Mohs Micrographic Surgery appropriate use criteria. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2020 Feb:82(2):e55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.064. Epub 2018 Dec 23 [PubMed PMID: 30586610]

Blechman AB, Patterson JW, Russell MA. Application of Mohs micrographic surgery appropriate-use criteria to skin cancers at a university health system. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2014 Jul:71(1):29-35. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.02.025. Epub 2014 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 24813300]

Coldiron B. Commentary: Implementation of the appropriate-use criteria will not increase Mohs micrographic surgery utilization. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2014 Jul:71(1):36-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.049. Epub 2014 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 24813301]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceReeder VJ, Gustafson CJ, Mireku K, Davis SA, Feldman SR, Pearce DJ. Trends in Mohs surgery from 1995 to 2010: an analysis of nationally representative data. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2015 Mar:41(3):397-403. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000285. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25705954]

Kantor J. Mohs Appropriate Use Criteria for Superficial Basal Cell Carcinoma. JAMA dermatology. 2019 Mar 1:155(3):395. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4572. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30725088]

Wong E, Axibal E, Brown M. Mohs Micrographic Surgery. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2019 Feb:27(1):15-34. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2018.08.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30420068]

Hope RH, Dowdle TS, Hope L, Pruneda C. Mohs micrographic surgery for keratinocyte carcinomas: clinicopathological predictors of the number of stages. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 2023:36(5):608-615. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2023.2236478. Epub 2023 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 37614851]

Huber C. [Interprofessional Collaboration in Health Care]. Praxis. 2022 Jan:110(1):3-4. doi: 10.1024/1661-8157/a003808. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34983202]

O'Hern K, Yang E, Vidal NY. ChatGPT underperforms in triaging appropriate use of Mohs surgery for cutaneous neoplasms. JAAD international. 2023 Sep:12():168-170. doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2023.06.002. Epub 2023 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 37404248]

Wolz MM. Two become one: Ethics in dermatologic surgery. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2015 Jun:72(6):1074-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1137. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25981003]