Introduction

Onychomycosis is a fungal infection of the nail unit. When dermatophytes cause onychomycosis, this condition is called tinea unguium.[1] The term onychomycosis encompasses the dermatophytes, yeasts, and saprophytic mold infections. An abnormal nail not caused by a fungal infection is a dystrophic nail. Onychomycosis can infect both fingernails and toenails, but onychomycosis of the toenail is much more prevalent. Discussed in detail in the following sections are all evolving facets of the topic, including disease burden, clinical types, staging, diagnosis, and management of toenail onychomycosis.[2][3][4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The most frequent cause of onychomycosis is Trichophyton rubrum, but other dermatophytes, including Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Epidermophyton floccosum, can also cause it. The dermatophytes are identified in 90% of the toenail and 50% of fingernail onychomycosis.[5] Candida albicans cases account for 2% of onychomycosis, especially in fingernails. Nondermatophytic mold onychomycosis is cultured primarily from toenails. Examples of these saprophytic molds include Fusarium, Aspergillus, Acremonium, Scytalidium, and Scopulariopsis brevicaulis,[6] accounting for about 8% of nail infections.[7]

Epidemiology

Onychomycosis is a common infection that is increasing in incidence. Initially, in the United States, Trichophyton rubrum was thought to be a culture contaminant. However, since the advent of international travel to Asia, T. rubrum has become the dominant causative organism in the United States.[8] At least half of abnormal toenails are mycotic. Prevalence estimates range from 1% to 8%, and the incidence is increasing. Patients are genetically susceptible to dermatophyte infections in an autosomal dominant pattern. Risk factors include aging, diabetes, tinea pedis, psoriasis, immunodeficiency, and living with family members with onychomycosis.[9][10]

Pathophysiology

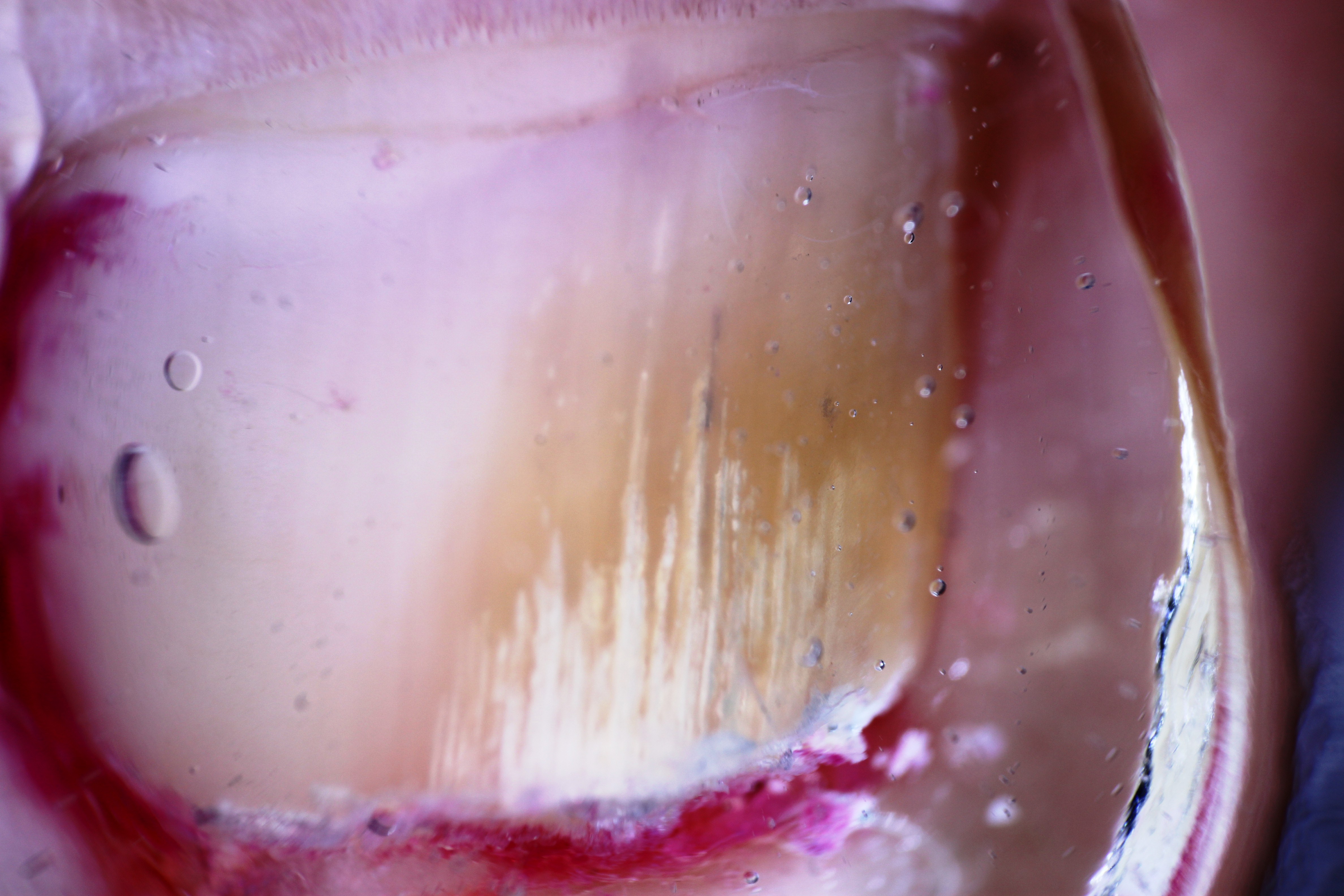

Hotel carpets, public showers, and pool decks can culture causative organisms. An asymptomatic, dry hyperkeratotic tinea pedis usually preceeds onychomycosis. Over time, the dark, warm, moist environment of shoes and micro traumatic pressure on the nail unit compromise and break the hyponychial seal, allowing penetration of the dermatophyte into the nail bed (Figure 1. Left Hallux Nail Plate). Repeated exposure to water in wet work compromises fingernails. Dermatophytes only live on the keratin of dead corneocytes in the skin, nails, and hair.[11]

In the foot, the dermatophytes produce keratinases that begin the infection between the lesser toes, spread to the hyperkeratotic sole, and gradually extend to the distal hyponychial space of micro-traumatized nail units. The dermatophytes breach and infect the nail bed through the distal nail hyponychail, spreading proximally as onycholysis and subungual hyperkeratosis.[12][13]

The primary site of the infection is the nail bed, where the acute infection occurs with a low-grade inflammatory response and progresses to a chronic phase of the nail bed infection as total dystrophic onychomycosis. Histologically, the acute lesion of onychomycosis manifests as spongiosis, acanthosis, papillomatosis with edema, and hyperkeratosis. These signs resemble psoriasis pathology.[14] As in most infections, a dense inflammatory infiltrate develops. Onychomycosis also eventually infects the viable nail matrixOnychomycosis Nail Changes. Onychomycosis secondarily damages the nail matrix as the nail bed becomes hyperkeratotic and thickened to shed the fungal infection. The dermatophyte also invades the overlying nail plate, detaching and distorting it over time (Figure 2. White Superficial Onychomycosis). The nail plate becomes elevated and misaligned as the infection enters the chronic total dystrophic clinical stage of onychomycosis (TDO) (Figure 3. Onychomycosis Nail Changes).[15] At this chronic stage of the infection, there are large amounts of compact hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis with sparse perivascular infiltrate. Dermatophytosis and subungual seromas can occur.[16] Zaikovska et al found high levels of cytokines interleukin-6- and interleukin-10-positive cells in the nail bed as well as the bloodstream in onychomycosis. Many fibers containing human beta defensin-2 can be in the bed and plate of the mycotic nails.

Histopathology

Histologically, the acute lesion of onychomycosis manifests as spongiosis, acanthosis, papillomatosis with edema, and hyperkeratosis. At the chronic stage of the infection, there are large amounts of compact hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis with sparse perivascular infiltrate. Dermatophytosis and subungual seromas can occur.[16]

History and Physical

The duration, progression, and success of previous treatments are all important aspects of the evaluation of a patient with nail disease. In addition, in suspected onychomycosis, medication history is important to assess the potential impact of systemic antifungals with current medications.[10] A history of hepatitis or travel to areas where hepatitis is endemic is an important aspect in considering appropriate tests to order in the laboratory workup. Alcohol usage should be properly chronicled. Recreational activities can predispose patients to recurrence or reinfection. Tinea manuum, cruris, or psoriasis often accompany onychomycosis. The focused cutaneous examination should include special attention to both hands, feet, and scalp.[17]

Pedal onychomycosis often presents as one or more thickened, discolored toenails. Usually, one or both great toenails are affected. Most cases have concurrent mild, dry, hyperkeratotic tinea pedis that patients often mistake for simple xerosis.[18] Baseline images of the target nail and measuring the extent of the infection are important to predict the duration of treatment and evaluate therapeutic progress in an infection that can take 12 months to clear. Estimate toenail growth at approximately one millimeter per month and measure the infected area of the nail unit to estimate the duration of the treatment. Keep in mind that fingernails grow faster than toenails, and aging and peripheral vascular insufficiency slow growth rates.

Evaluation

Determining the severity and clinical stage of the infection helps guide therapy and improves outcomes. The most common clinical subtype of onychomycosis is distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (DSLO) (Figure 4. Lateral Onychomycosis).[19] This condition presents as partial distal onycholysis with subungual hyperkeratosis or crumbling. Much less common is white superficial onychomycosis (WSO), which appears as white, chalky deposits on the surface of the affected nail plate.[20] WSO is easily scraped away with a curette or rotary burr.[21] The rarest subtype of onychomycosis is proximal subungual onychomycosis (PSO), which develops overlying the nail matrix.[22] PSO has been associated with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and spreads through a hematogenous route. Infected first is the interior of the nail plate, and the key feature of subungual hyperkeratosis of the nail bed is not evident in the endonyx subtype.[23] Total dystrophic onychomycosis (TDO) is the most advanced form. TDO is a later severe stage of the chronic subungual dermatophyte infection that may take 10 to 15 years to develop. Significant subungual hyperkeratosis accompanies TDO, and destruction of the abnormal nail plate and ridging of the nail bed may ensue. This is not only the most challenging stage to clear but also the type with the highest risk of developing subungual ulcerations, secondary bacterial infection, and precipitating gangrene in patients with impaired peripheral circulation.[24][25][26]

It is essential to know that almost half of the abnormal-appearing toenails are not mycotic, so mycological testing is vital to establish an accurate diagnosis and is especially important if systemic therapy is planned. The traditional potassium hydroxide (KOH) wet mount preparation of subungual debris is only 60% sensitive but cannot identify the species. However, if the KOH is positive, it can separate dermatophytes from saprophytes.[27] Currently, the most sensitive test (95%) is a pathologist-interpreted nail clip biopsy stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) plus Grocott methenamine silver. Today, a mycologist is required to interpret fungal culture testing. Fungal cultures are very specific but not very sensitive (60%). Fungal cultures grow slowly, adding weeks and costs to the workup.

Fungal culture or PCR is required to specify the infection's cause. They are helpful in determining the source of the infection in atypical cases or when one suspects a primary saprophytic infection. Confirm this suspicion by obtaining 2 subsequent cultures of the same saprophytic before concluding that the saprophyte is the primary pathogen and not a contaminant. PCR improves the species-specific detection of dermatophytes by 20% over fungal cultures alone.[28]

Dermoscopy can clinically diagnose onychomycosis and can also readily differentiate between onychomycosis and nail dystrophy (Figure 5. Onychomycosis, Aurora Borealis). The presence of subungual short spikes and longitudinal striae indicates onychomycosis, while transverse onycholysis is consistent with microtraumatic nail dystrophy (Figure 6. Onychomycosis, Longitudinal Striae. ).[29]

Treatment / Management

The most effective treatments for onychomycosis are systemic antifungals. Due to an increased risk of subungual ulceration, one also should consider oral antifungal therapy in moderate to severe disease, especially in patients with diabetes mellitus. Combination therapy with topical agents, periodic debridement, or chemical nail avulsion may produce better results than systemic medication alone. The newer topical antifungal therapies have improved cure rates for mild to moderate cases in patients who prefer to avoid systemic antifungals. Meta-analyses have shown the mycological cure rate for terbinafine is 76%, itraconazole pulse dosing is 63%, and fluconazole is 48% effective. Conversely, topical therapy mycological cure rates are 55% for efinaconazole and 36% for tavaborole or ciclopirox.[12][30][31]

Negative mycology and 100% clear nail, the gold standard for comparing efficacies, define the complete cure rate. However, this is a very stringent criterion as residual nail dystrophy from chronic infection may scar the nail plate and not allow some results to be completely clear—even though there may be a significant clinical improvement. On the other hand, the nail unit could be 100% clear, but the post-treatment fungal culture may detect fungal colonization. The complete cure rate for systemic terbinafine is 38%. [32]

Oral therapy is the most effective therapy for severe onychomycosis but is medically inappropriate for some patients. Additionally, many patients have a strong personal preference for a non-systemic approach. Topical therapy is a good solution to the problem if the efficacy rates are better. Many over-the-counter and prescription products are available, suggesting no effective topical choices exist. The evidence concludes that complete cure rates for FDA-approved topical therapies have recently improved from 8.5% for ciclopirox lacquer to 18% for an efinaconazole solution.[33] The tavaborole solution has a complete cure rate of 9.1% in mild to moderate distal subungual onychomycosis.[34]

It is essential to carefully review the patient history of alcohol use disorder and hepatitis. Ordering alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase hepatic function tests before the beginning of continuous therapy establishes a baseline. If there is a history of living overseas where hepatitis is endemic, add a hepatitis antigen screening panel to the workup. Follow-up hepatic function tests at 5 weeks can detect less than 2% of idiosyncratic reactions. One can stop the drug and retest if the follow-up tests are significantly elevated.[35](B2)

Additionally, concurrent medications may preclude the use of oral antifungals. Terbinafine may alter the metabolism of many drugs, so monitoring is appropriate. Concerns regarding drug-to-drug interactions with statin therapy and systemic antifungal therapy are actually with the azole class of antifungals and not terbinafine.[36] Avoiding systemic therapy in patients on psychotropic medications might be best. Terbinafine carries a contraindication for concurrent use with phenothiazines and pimozide for increased risk of QT prolongation.[37] One can use terbinafine safely in children and the elderly. However, clinicians should always exercise caution in patients with polypharmacy. Using an alternative therapy or periodic debridement alone to control symptoms in these cases (to avoid adverse drug reactions in patients with essentially benign disease) may be best. (B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Differentiate onychomycosis by other similar nail pathologies, including

- Yellow nail syndrome

- Drug reaction

- Hypothyroidism

- Nail malignancy

- Psoriatic nail

- Contact dermatitis

Prognosis

The prognosis of onychomycosis varies depending on several factors, including:

- Type and severity of infection: The type of fungus and the extent of the involvement of infection can affect the prognosis, with limited and superficial infections resulting in better outcomes.

- Immune system status: Immunocompromised people, such as those with diabetes, HIV, or other immunodeficiency conditions, may experience a more chronic course of disease.[11]

- Response to treatment: The effectiveness of the chosen regimen plays a crucial role in the prognosis. Some cases of onychomycosis can be successfully treated with antifungal oral and topical treatments, leading to complete resolution. However, in some cases, the infection may resist conventional treatment, leading to a more prolonged or recurring condition.

- Compliance with treatment: Adherence to the prescribed treatment plan is necessary for a favorable prognosis. Non-compliance can lead to chronic infection.[38]

- Underlying health conditions: Certain medical conditions, such as poor circulation or peripheral vascular disease, can affect blood flow to the nails and impede the effectiveness of systemic treatment, leading to slowed improvement.

Complications

While the infection is not fatal, some of the complications seen in patients with the condition include the following:

- Cellulitis

- Sepsis

- Osteomyelitis

- Tissue damage

- Loss of nail

Deterrence and Patient Education

Encourage patients to wear proper footwear, maintain hygiene, and be conscious about cleaning their hands and feet when using public washrooms, pools, or water parks, and they should not use wet towels. If there is any change in the nails, patients should see the clinician for a timely diagnosis and treatment. Once commencing treatment, patients should be guided about compliance, as non-adherence to medication can change the course of the disease.

Pearls and Other Issues

To control symptoms and reduce the risks of subungual ulceration and secondary bacterial infection, clinicians can use periodic debridement to successfully manage severe onychomycosis in patients who elect to avoid systemic therapy or cannot apply topical antifungals. In addition, many patients are reluctant to accept the potential risk of idiosyncratic hepatic reactions that may occur during 90 days of continuous systemic antifungal therapy. Some patients will, however, accept and do well with pulsed systemic therapy. In moderate onychomycosis, 250 mg of terbinafine daily for 1 week, every 9 weeks for 3 pulses is acceptable. Although periodic thorough debridement is unlikely to clear onychomycosis, it appears to improve immediate patient satisfaction and aid the efficacy of medications. Undertake concurrent treatment of the tinea pedis and the long-term daily use of an antifungal powder to reduce reinfection and recurrence.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The effective management of onychomycosis requires an interprofessional approach. While the fungal infection is not life-threatening, this condition has enormous morbidity, and the key to success is patient education. When visiting community swimming pools, saunas, and health clubs, the public should be educated about appropriate footwear. If the patient works in a wet environment, like washing dishes, they should be encouraged to wear gloves. A family physician or dermatologist usually diagnoses the disease after a detailed examination. The pharmacist should inform the patient that treatment time can take at least 12 months, and some patients may require prophylactic treatment to prevent a recurrence. Pharmacists should also monitor compliance and educate patients about use and side effects. Dermatology and foot and nail care nurses are involved in screening, arranging follow-ups, and documenting progress and compliance for the team. Refer patients who want a faster option to a dermatologist or a surgeon for complete nail removal.[38][39]

For patients who delay seeking care, nail deformity usually progresses and may lead to disfigurement and pain. Even though antifungal drugs are available, the treatment often takes months or years before one sees an obvious improvement.[40] Several studies have shown that terbinafine is more effective than other antifungals. However, individuals with yellow streaks along the lateral nail border tend to have poor responses to treatment. Overall, fungal infections of the toenails have a much poorer outcome than fingernail infections. Finally, despite treatment, there is a high recurrence rate, ranging from 5%-50%.[41][42] Therefore, prompt commencement of treatment and follow-ups are mandatory.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Asz-Sigall D, Tosti A, Arenas R. Tinea Unguium: Diagnosis and Treatment in Practice. Mycopathologia. 2017 Feb:182(1-2):95-100. doi: 10.1007/s11046-016-0078-4. Epub 2016 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 27787643]

Karaman BFO, Açıkalın A, Ünal İ, Aksungur VL. Diagnostic values of KOH examination, histological examination, and culture for onychomycosis: a latent class analysis. International journal of dermatology. 2019 Mar:58(3):319-324. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14255. Epub 2018 Sep 23 [PubMed PMID: 30246397]

Haghani I, Shams-Ghahfarokhi M, Dalimi Asl A, Shokohi T, Hedayati MT. Molecular identification and antifungal susceptibility of clinical fungal isolates from onychomycosis (uncommon and emerging species). Mycoses. 2019 Feb:62(2):128-143. doi: 10.1111/myc.12854. Epub 2018 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 30255665]

Becker BA, Childress MA. Common Foot Problems: Over-the-Counter Treatments and Home Care. American family physician. 2018 Sep 1:98(5):298-303 [PubMed PMID: 30216025]

Appelt L, Nenoff P, Uhrlaß S, Krüger C, Kühn P, Eichhorn K, Buder S, Beissert S, Abraham S, Aschoff R, Bauer A. [Terbinafine-resistant dermatophytoses and onychomycosis due to Trichophyton rubrum]. Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift fur Dermatologie, Venerologie, und verwandte Gebiete. 2021 Oct:72(10):868-877. doi: 10.1007/s00105-021-04879-1. Epub 2021 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 34459941]

Pote ST, Khan U, Lahiri KK, Patole MS, Thakar MR, Shah SR. Onychomycosis due to Achaetomium strumarium. Journal de mycologie medicale. 2018 Sep:28(3):510-513. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2018.07.002. Epub 2018 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 30104134]

Youssef AB, Kallel A, Azaiz Z, Jemel S, Bada N, Chouchen A, Belhadj-Salah N, Fakhfakh N, Belhadj S, Kallel K. Onychomycosis: Which fungal species are involved? Experience of the Laboratory of Parasitology-Mycology of the Rabta Hospital of Tunis. Journal de mycologie medicale. 2018 Dec:28(4):651-654. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2018.07.005. Epub 2018 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 30107987]

Gupta AK, Versteeg SG, Shear NH. Onychomycosis in the 21st Century: An Update on Diagnosis, Epidemiology, and Treatment. Journal of cutaneous medicine and surgery. 2017 Nov/Dec:21(6):525-539. doi: 10.1177/1203475417716362. Epub 2017 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 28639462]

Arsenijević VA, Denning DW. Estimated Burden of Serious Fungal Diseases in Serbia. Journal of fungi (Basel, Switzerland). 2018 Jun 25:4(3):. doi: 10.3390/jof4030076. Epub 2018 Jun 25 [PubMed PMID: 29941824]

Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: Clinical overview and diagnosis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2019 Apr:80(4):835-851. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.062. Epub 2018 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 29959961]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAragón-Sánchez J, López-Valverde ME, Víquez-Molina G, Milagro-Beamonte A, Torres-Sopena L. Onychomycosis and Tinea Pedis in the Feet of Patients With Diabetes. The international journal of lower extremity wounds. 2023 Jun:22(2):321-327. doi: 10.1177/15347346211009409. Epub 2021 Apr 23 [PubMed PMID: 33891512]

Drago L, Micali G, Papini M, Piraccini BM, Veraldi S. Management of mycoses in daily practice. Giornale italiano di dermatologia e venereologia : organo ufficiale, Societa italiana di dermatologia e sifilografia. 2017 Dec:152(6):642-650. doi: 10.23736/S0392-0488.17.05683-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29050446]

Maddy AJ, Tosti A. Hair and nail diseases in the mature patient. Clinics in dermatology. 2018 Mar-Apr:36(2):159-166. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.10.007. Epub 2017 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 29566920]

Zaikovska O, Pilmane M, Kisis J. Morphopathological aspects of healthy nails and nails affected by onychomycosis. Mycoses. 2014 Sep:57(9):531-6. doi: 10.1111/myc.12191. Epub 2014 Mar 24 [PubMed PMID: 24661598]

Vlahovic TC, Garcia M, Wotring K. Dermoscopy of Onychomycosis for the Podiatrist. Clinics in podiatric medicine and surgery. 2021 Oct:38(4):505-511. doi: 10.1016/j.cpm.2021.06.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34538427]

Nikitha S, Kondraganti N, Kandi V. Total Dystrophic Onychomycosis of All the Nails Caused by Non-dermatophyte Fungal Species: A Case Report. Cureus. 2022 Sep:14(9):e29765. doi: 10.7759/cureus.29765. Epub 2022 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 36324367]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGupta AK, Studholme C. Novel investigational therapies for onychomycosis: an update. Expert opinion on investigational drugs. 2016:25(3):297-305. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2016.1142529. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26765142]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDaggett C, Brodell RT, Daniel CR, Jackson J. Onychomycosis in Athletes. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2019 Oct:20(5):691-698. doi: 10.1007/s40257-019-00448-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31111408]

Yadav P, Singal A, Pandhi D, Das S. Clinico-mycological study of dermatophyte toenail onychomycosis in new delhi, India. Indian journal of dermatology. 2015 Mar-Apr:60(2):153-8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.152511. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25814703]

Grover C, Jakhar D, Sharma S. The grid pattern of white superficial onychomycosis. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2020 Sep-Oct:86(5):568-570. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_699_19. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32769307]

Almeida HL Jr, Boabaid RO, Timm V, Silva RM, Castro LA. Scanning electron microscopy of superficial white onychomycosis. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2015 Sep-Oct:90(5):753-5. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20154136. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26560225]

Mehta M, Sharma J, Bhardwaj SB. Proximal subungual onychomycosis of digitus minimus due to Aspergillus brasiliensis. The Pan African medical journal. 2020:35():79. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2020.35.79.20762. Epub 2020 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 32537082]

Bunyaratavej S, Bunyaratavej S, Muanprasart C, Matthapan L, Varothai S, Tangjaturonrusamee C, Pattanaprichakul P. Endonyx onychomycosis caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2015 Jul-Aug:81(4):390-2. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.157460. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25994895]

Hay R. Therapy of Skin, Hair and Nail Fungal Infections. Journal of fungi (Basel, Switzerland). 2018 Aug 20:4(3):. doi: 10.3390/jof4030099. Epub 2018 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 30127244]

Hayette MP, Seidel L, Adjetey C, Darfouf R, Wéry M, Boreux R, Sacheli R, Melin P, Arrese J. Clinical evaluation of the DermaGenius® Nail real-time PCR assay for the detection of dermatophytes and Candida albicans in nails. Medical mycology. 2019 Apr 1:57(3):277-283. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myy020. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29762721]

Chetana K, Menon R, David BG. Onychoscopic evaluation of onychomycosis in a tertiary care teaching hospital: a cross-sectional study from South India. International journal of dermatology. 2018 Jul:57(7):837-842. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14008. Epub 2018 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 29700806]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGupta AK, Hall DC, Cooper EA, Ghannoum MA. Diagnosing Onychomycosis: What's New? Journal of fungi (Basel, Switzerland). 2022 Apr 29:8(5):. doi: 10.3390/jof8050464. Epub 2022 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 35628720]

Pospischil I, Reinhardt C, Bontems O, Salamin K, Fratti M, Blanchard G, Chang YT, Wagner H, Hermann P, Monod M, Hoetzenecker W, Guenova E. Identification of Dermatophyte and Non-Dermatophyte Agents in Onychomycosis by PCR and DNA Sequencing-A Retrospective Comparison of Diagnostic Tools. Journal of fungi (Basel, Switzerland). 2022 Sep 27:8(10):. doi: 10.3390/jof8101019. Epub 2022 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 36294584]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLitaiem N, Mnif E, Zeglaoui F. Dermoscopy of Onychomycosis: A Systematic Review. Dermatology practical & conceptual. 2023 Jan 1:13(1):. doi: 10.5826/dpc.1301a72. Epub 2023 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 36892372]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLok C. [What's new in clinical dermatology?]. Annales de dermatologie et de venereologie. 2016 Dec:143 Suppl 3():S1-S10. doi: 10.1016/S0151-9638(18)30043-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29429503]

Wollina U, Nenoff P, Haroske G, Haenssle HA. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Nail Disorders. Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 2016 Jul 25:113(29-30):509-18. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0509. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27545710]

Aggarwal R, Targhotra M, Kumar B, Sahoo PK, Chauhan MK. Treatment and management strategies of onychomycosis. Journal de mycologie medicale. 2020 Jun:30(2):100949. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2020.100949. Epub 2020 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 32234349]

Gupta AK, Talukder M. Efinaconazole in Onychomycosis. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2022 Mar:23(2):207-218. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00660-1. Epub 2021 Dec 13 [PubMed PMID: 34902110]

Frazier WT, Santiago-Delgado ZM, Stupka KC 2nd. Onychomycosis: Rapid Evidence Review. American family physician. 2021 Oct 1:104(4):359-367 [PubMed PMID: 34652111]

Wang Y, Geizhals S, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of laboratory abnormalities in patients prescribed terbinafine for onychomycosis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2021 Feb:84(2):497-499. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.172. Epub 2020 May 7 [PubMed PMID: 32387655]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLipner SR, Joseph WS, Vlahovic TC, Scher RK, Rich P, Ghannoum M, Daniel CR, Elewski B. Therapeutic Recommendations for the Treatment of Toenail Onychomycosis in the US. Journal of drugs in dermatology : JDD. 2021 Oct 1:20(10):1076-1084. doi: 10.36849/JDD.6291. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34636509]

Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Safety of current therapies for onychomycosis. Expert opinion on drug safety. 2020 Nov:19(11):1395-1408. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2020.1829592. Epub 2020 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 32990062]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: Treatment and prevention of recurrence. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2019 Apr:80(4):853-867. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.1260. Epub 2018 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 29959962]

Hanna S, Andriessen A, Beecker J, Gilbert M, Goldstein E, Kalia S, King A, Kraft J, Lynde C, Singh D, Turchin I, Zip C. Clinical Insights About Onychomycosis and Its Treatment: A Consensus. Journal of drugs in dermatology : JDD. 2018 Mar 1:17(3):253-262 [PubMed PMID: 29537443]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZeichner JA. Onychomycosis to Fungal Superinfection: Prevention Strategies and Considerations. Journal of drugs in dermatology : JDD. 2015 Oct:14(10 Suppl):s32-4 [PubMed PMID: 26461832]

Shemer A, Gupta AK, Babaev M, Barzilai A, Farhi R, Daniel Iii CR. A Retrospective Study Comparing K101 Nail Solution as a Monotherapy and in Combination with Oral Terbinafine or Itraconazole for the Treatment of Toenail Onychomycosis. Skin appendage disorders. 2018 Aug:4(3):166-170. doi: 10.1159/000484211. Epub 2017 Nov 16 [PubMed PMID: 30197895]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSalakshna N, Bunyaratavej S, Matthapan L, Lertrujiwanit K, Leeyaphan C. A cohort study of risk factors, clinical presentations, and outcomes for dermatophyte, nondermatophyte, and mixed toenail infections. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2018 Dec:79(6):1145-1146. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.041. Epub 2018 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 29860042]