Introduction

Mastocytosis is a disorder characterized by mast cell accumulation, commonly in the skin, bone marrow, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, liver, spleen, and lymphatic tissues. The World Health Organization (WHO) divides cutaneous mastocytosis into 3 main presentations. The first has solitary or few (≤3) lesions called "mastocytomas." The second, urticaria pigmentosa (UP), involves multiple lesions ranging from >10 to <100 lesions. The last presentation involves diffuse cutaneous involvement.

UP is the most common cutaneous mastocytosis in children, but it can form in adults as well. It is considered a benign, self-resolving condition that often remits in adolescence. Unlike adult forms of mastocytosis, there is rarely any internal organ involvement in UP.[1]

What makes UP particularly distinctive is its tendency to manifest as small, itchy, reddish-brown, or yellowish-brown spots or lesions on the skin, commonly referred to as "urticaria" or hives. These spots typically appear in childhood and can persist throughout a person's life. The condition can vary in severity, and while it is often benign, it may sometimes cause symptoms and complications related to mast cell activation. Understanding the features, causes, and management of UP is essential for healthcare professionals.[2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

UP is caused by several activating mutations in the KIT gene. When exposed to certain triggers, mast cells release mediators that cause the symptoms of mastocytosis. The released mediators are histamine, eicosanoids, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, heparin, proteases, and cytokines. Triggers include certain foods, exercise, heat, Hymenoptera and venomous stings, local trauma to skin lesions, alcohol, narcotics, salicylates and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), polymyxin B, and anticholinergic medications. Some systemic anesthetic agents may induce anaphylaxis.[3]

Epidemiology

Mastocytosis can present at birth or develop at any time into late adulthood. It occurs in all races and has no gender preferences. Although most patients do not have a family history of mastocytosis, familial cases have been reported.[4] Cutaneous mastocytomas occur in 15% to 50% of patients, while UP occurs in 45% to 75%, and diffuse cutaneous involvement occurs in less than 5% to 10% of mastocytosis patients. Most reported cases are in whites. The cutaneous lesions of most types of mastocytosis are less visible in persons with more heavily pigmented skin. The apparent prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in children with mastocytosis was found to be 10 times higher than in the general population.[5]

Pathophysiology

Mast cell precursors express CD34, the tyrosine kinase receptor KIT (CD117), and IgG receptors (Fc gamma RII). KIT can be activated by its ligand, stem cell factor (SCF), which induces mast cell growth and maturation and prevents apoptosis. Bone marrow stromal cells, keratinocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and reproductive Sertoli and granulosa cells produce SCF. The pathogenesis of mastocytosis is due to several mutations in KIT. The most common is an activating mutation in codon 816, where there is a substitution of the amino acid aspartic acid (D) with valine (V, ie, D816V) or another amino acid. These amino acids result in constitutive ligand-independent activation of the receptor. Other additional pathogenic factors exist that still need more research.[6][7] The increased concentrations of soluble mast cell growth factor in lesions of cutaneous mastocytosis are believed to stimulate mast cell proliferation, melanocyte induction, and melanin pigment production. The induction of melanocytes explains the hyperpigmentation that is commonly seen in cutaneous mast cell lesions. The stimulation of pruritus reported in mastocytosis is associated with the production of interleukin (IL)–31.[8] Impaired mast cell apoptosis has been postulated to be involved, as evidenced by the up-regulation of the apoptosis-preventing protein BCL-2 demonstrated in the patients.[9] IL-6 levels are elevated and correlated with disease severity, indicating the involvement of IL-6 in the pathophysiology of mastocytosis.[10]

Histopathology

Diagnosis of UP can be made clinically. However, a definitive diagnosis requires a skin biopsy. An anesthetic agent should be injected without epinephrine adjacent to, not directly into, the lesion chosen as the biopsy specimen to avoid mast cell degranulation, which makes histologic examination difficult.

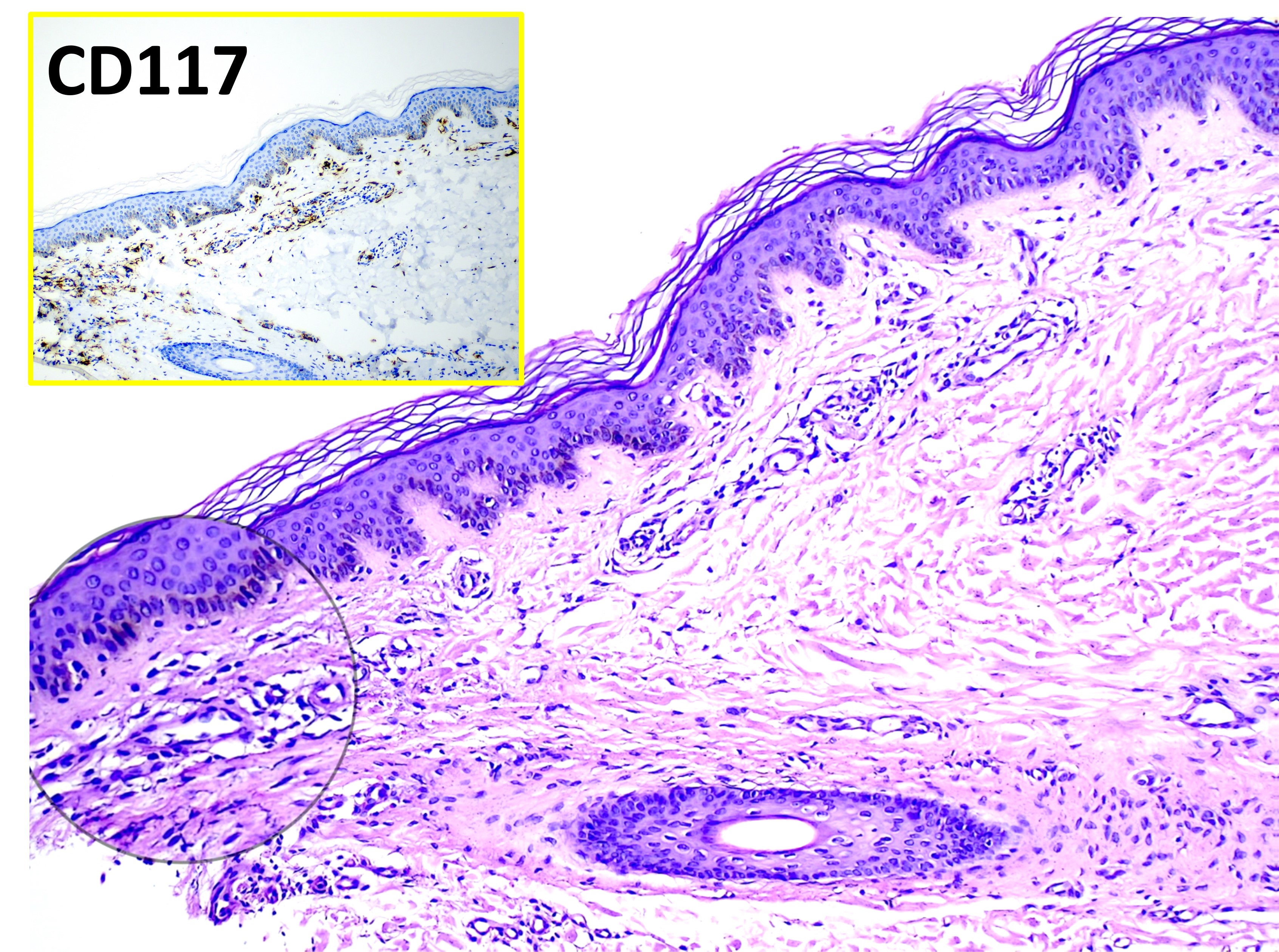

The hallmark finding histologically for UP is having an increased amount of mast cells in the dermis. UP skin lesions can have a 40-fold higher mast cell count than normal skin.[11] Mast cells have a rounded or cuboidal appearance (see Image. Mastocytosis). Mast cell nuclei are rounded with surrounding ample cytoplasm, producing a “fried egg” appearance. The typical presentation of mast cells is a single nucleus, yet there have also been atypical histological findings reported in 4 patients with UP that showed mast cells with bilobed and multilobed morphology.[12] In nodular UP, mast cells are observed in dense aggregates and may extend through the entire dermis and into subcutaneous tissue.

If the lesion from which the biopsy specimen was taken was traumatized during harvest, edema and eosinophil infiltrates may be present. The hyperpigmentation of cutaneous mastocytosis is secondary to increased melanin in the basal cell layer and melanophages in the upper dermis. Stains that help identify mast cells include toluidine blue, Leder, Giemsa, tryptase, and CD117 (KIT). Biopsy specimens from normal skin in patients with mastocytosis will not show an increased amount of mast cells. Therefore, if there are no skin lesions and systemic mastocytosis is suspected, a bone marrow biopsy or biopsy from the GI tract may be needed. A total serum tryptase level can help identify the extent of mast cell disease. A tryptase level >20 ng/ml represents 1 of the minor criteria for systemic mastocytosis.[13]

History and Physical

UP has small, monomorphic tan to brown macules or papules distributed mainly on the trunk and classically spares the central face, palms, and soles (see Image. Urticaria Pigmentosa). It is similar to the lesions typically observed in adults. Lesions can be few or numerous and are usually about 1 to 2 cm in size; however, they can be larger. Darier’s sign is the formation of a wheal upon stroking or rubbing skin lesions and suggests the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis. The wheal forms due to the release of mast cell mediators, which can contribute to the systemic symptoms that may occur after stroking the lesion. Some lesions may blister after stroking the lesion. Darier’s sign is more pronounced in children than in adults due to an increased density of mast cells in lesions of children. In approximately half of the patients, stroking macroscopically uninvolved skin produces dermographia. Large hemorrhagic bullous and infiltrative small vesicular variants occur. Blistering predominates in infancy, whereas the grain-leather appearance of the skin and pseudoxanthomatous presentation develop with time. Anaphylactic shock may occur.

Systemic symptoms can occur, such as pruritus, abdominal pain, flushing, diarrhea, dizziness, palpitations, and syncope. Twenty-five percent of the patients with UP experience gastrointestinal symptoms. Complaints of fever, malaise, night sweats, bone pain, epigastric distress, weight loss, and problems with cognitive disorganization often signal the presence of extracutaneous disease. Death can even occur from the extensive mast cell mediator release.[14]

Evaluation

If the patient complains of GI symptoms, a barium study or endoscopy may be needed. If a patient complains of bone pain or fractures, a radiographic skeletal survey or bone scan may be needed. On examination, it is important to look for lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. If an abnormality is suspected, a liver ultrasound or CT scan should be ordered to investigate. If there are abnormal findings in any of the tests, a biopsy of the bone marrow should be considered. A complete blood count (CBC), serum tryptase level, liver function tests, and KIT gene analysis can be ordered. However, it is considered by some to be optional in the pediatric population. If there are any abnormalities, a bone marrow biopsy should be considered. Bone marrow involvement is not very common in children with cutaneous mastocytosis, unlike adults, and a bone marrow biopsy is not recommended. Tryptase levels may be more useful than histamine levels because histamine can be elevated in hypereosinophilic states. It is important to learn the criteria for systemic mastocytosis in case a patient progresses.[15]

The WHO criterion for the diagnosis of systemic mastocytosis states that you need 1 major and 1 minor criteria or 3 minor criteria.

Major Criteria

- Having multifocal, dense infiltrates of mast cells (aggregates ≥15 mast cells) in bone marrow or extracutaneous tissues.

Minor Criteria

- >25% of mast cells in bone marrow samples or extracutaneous tissues are spindle-shaped or otherwise atypical.

- Expression of CD25 and/or CD2 by extracutaneous mast cells (often determined by bone marrow flow cytometry)

- Presence of activating KIT codon 816 mutation in blood, bone marrow, or extracutaneous tissues.

- Serum total tryptase level >20 ng/ml (exception would be an associated clonal myeloid disorder, then this is not valid).

The criterion for diagnosing cutaneous mastocytosis is not well-defined. Cutaneous mastocytosis is usually diagnosed by visual evaluation of typical skin lesions, particularly in children. However, there is a stepwise approach to diagnose mastocytosis in the skin; it must have 1 major and 1 minor criterion.

Major Criteria

- Must have the typical skin lesions.

Minor Criteria

- Histology (monomorphic mast cell infiltrate with aggregates of >15 mast cells per cluster or scattered mast cells with >20 per high microscopic power field).

- Molecular criterion (detection of a KIT mutation at codon 816 in the affected skin).[13]

Treatment / Management

The management of cutaneous mastocytosis begins with practical measures, such as the use of lukewarm water for bathing, air conditioning during hot weather, and avoidance of triggers for mast cell degranulation. Treatment is symptomatic for patients with cutaneous mastocytosis.

Topical medications include calcineurin inhibitors and corticosteroids (a potent class 1 topical corticosteroid, with occlusion if required). Intralesional injections of small amounts of dilute corticosteroids may resolve skin lesions temporarily or indefinitely. The risk of skin atrophy and adrenocortical suppression resulting from the treatment is minimized by treating limited body areas during a single treatment session.

Systemic corticosteroids are useful only in specific situations, such as ascites, malabsorption, and severe skin disease. Case reports have described complete remission of bullous mastocytosis with oral corticosteroids,[16] but systemic therapy is often disappointing because the primary mode of action of corticosteroids is redistribution rather than the death of mast cells. Systemic therapies such as oral antihistamines (the mainstay of treatment), oral cromolyn sodium (explicitly used for GI symptoms), omalizumab, oral PUVA, narrowband ultraviolet B, and UVA1 can be used. A pre-measured epinephrine pen with an auto-injector should be given to all UP patients.(B3)

Cutaneous mastocytosis patients should avoid certain physical stimuli, including emotional stress, temperature extremes, physical exertion, bacterial toxins, envenomation by insects to which the patient is allergic, and rubbing, scratching, or traumatizing the lesions of cutaneous mastocytosis. Patients should also be educated to avoid possible triggers such as aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, codeine, morphine, alcohol, thiamine, quinine, opiates, gallamine, decamethonium, procaine, radiographic dyes, dextran, polymyxin B, scopolamine, and D-tubocurarine.[17] Crawfish, lobster, spicy foods, hot beverages, and cheese should be avoided. However, the role of the previously mentioned foods is hypothetical at this point and needs further investigation.[18] One successful case report described the treatment of progressive c-KIT mutation cutaneous mastocytosis with imatinib, halting disease symptoms and progression and improving the length of the disease course.[19](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Bullous impetigo, secondary syphilis, carcinoid, leiomyoma, urticaria, juvenile xanthogranuloma, arthropod stings, and auto-immune bullous diseases are differential diagnoses. Increased mast cell numbers can be found in other inflammatory and neoplastic skin conditions, such as dermatofibromas, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and nevi. However, these disorders are also associated with additional characteristic histopathological changes in the skin that differ from those of mastocytosis.[20]

Prognosis

The prognosis for childhood mastocytosis is excellent, with 50% to 70% of patients remitting before adolescence. Cutaneous mastocytosis onset after the age of 10 years portends a poorer prognosis because the late-onset disease tends to be persistent, is associated more often with systemic disease, and carries a higher risk of malignant transformation.[21]

Complications

Complications may include the possible transformation into a hematologic malignancy (mast cell leukemia) and death secondary to extensive mast cell degranulation.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence involves educating patients about potential triggers like specific foods, medications, insect stings, or physical stimuli that can exacerbate their condition. By recognizing and avoiding these triggers, patients can mitigate symptom flare-ups and improve their overall quality of life. Simultaneously, patient education plays a vital role in helping individuals understand the nature of UP, emphasizing its typically benign course and the rarity of internal organ involvement. Patients are also educated about the importance of proper medication management, lifestyle modifications, and regular follow-up appointments. The significance of early intervention and regular medical check-ups to prevent complications associated with mast cell activation should be emphasized. Patients must be taught to recognize signs of systemic involvement and seek medical attention promptly. Through a combination of deterrence strategies and comprehensive patient education, healthcare professionals empower those with UP to take an active role in managing their condition effectively and enhancing their well-being.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Healthcare professionals, including physicians, advanced care practitioners, nurses, and pharmacists, need to develop the skills necessary for diagnosing and managing UP. This includes the ability to recognize the characteristic skin lesions and differentiate them from other skin conditions. Clinicians should also possess skills in conducting thorough patient assessments and utilizing appropriate diagnostic tests to confirm the diagnosis.

A strategic approach to managing patients with UP involves staying updated on the latest research and treatment options. Healthcare professionals should create individualized treatment plans, including medications, lifestyle modifications, and patient education to manage the condition effectively.

Effective interprofessional communication is crucial in managing UP. Physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals must collaborate to ensure a holistic approach to care. Sharing information, insights, and treatment plans promotes optimal patient outcomes and safety.

The interprofessional team should coordinate care for patients with UP. This involves ensuring that all team members are on the same page regarding the patient's diagnosis and treatment plan. Timely and accurate information exchange and clear roles within the care team are essential for enhancing patient-centered care and safety. This collaborative approach promotes comprehensive care and improves the overall performance of the healthcare team in managing patients affected by this unique skin disorder.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Mastocytosis. The main image (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification ×100) shows varying numbers of dermal mast cells appearing as unremarkable histiocytoid cells. The inset highlights CD117-positive staining with immunohistochemistry, confirming mast cell proliferation.

Contributed by Mona Abdel-Halim Ibrahim, MD

References

Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, Brockow K, Carter MC, Alvarez-Twose I, Matito A, Broesby-Olsen S, Siebenhaar F, Lange M, Niedoszytko M, Castells M, Oude Elberink JNG, Bonadonna P, Zanotti R, Hornick JL, Torrelo A, Grabbe J, Rabenhorst A, Nedoszytko B, Butterfield JH, Gotlib J, Reiter A, Radia D, Hermine O, Sotlar K, George TI, Kristensen TK, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Yavuz S, Hägglund H, Sperr WR, Schwartz LB, Triggiani M, Maurer M, Nilsson G, Horny HP, Arock M, Orfao A, Metcalfe DD, Akin C, Valent P. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: Consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2016 Jan:137(1):35-45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.034. Epub 2015 Oct 21 [PubMed PMID: 26476479]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWassmer H, Hartmann K. [Mastocytosis in children]. Dermatologie (Heidelberg, Germany). 2023 May:74(5):323-329. doi: 10.1007/s00105-023-05168-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37140636]

Heinze A, Kuemmet TJ, Chiu YE, Galbraith SS. Longitudinal Study of Pediatric Urticaria Pigmentosa. Pediatric dermatology. 2017 Mar:34(2):144-149. doi: 10.1111/pde.13066. Epub 2017 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 28133781]

Lappe U, Aumann V, Mittler U, Gollnick H. Familial urticaria pigmentosa associated with thrombocytosis as the initial symptom of systemic mastocytosis and Down's syndrome. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2003 Nov:17(6):718-22 [PubMed PMID: 14761147]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTheoharides TC. Autism spectrum disorders and mastocytosis. International journal of immunopathology and pharmacology. 2009 Oct-Dec:22(4):859-65 [PubMed PMID: 20074449]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLongley BJ, Tyrrell L, Ma Y, Williams DA, Halaban R, Langley K, Lu HS, Schechter NM. Chymase cleavage of stem cell factor yields a bioactive, soluble product. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997 Aug 19:94(17):9017-21 [PubMed PMID: 9256427]

Doyle LA, Sepehr GJ, Hamilton MJ, Akin C, Castells MC, Hornick JL. A clinicopathologic study of 24 cases of systemic mastocytosis involving the gastrointestinal tract and assessment of mucosal mast cell density in irritable bowel syndrome and asymptomatic patients. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2014 Jun:38(6):832-43. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000190. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24618605]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFerretti E, Corcione A, Pistoia V. The IL-31/IL-31 receptor axis: general features and role in tumor microenvironment. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2017 Sep:102(3):711-717. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3MR0117-033R. Epub 2017 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 28408397]

Hartmann K, Artuc M, Baldus SE, Zirbes TK, Hermes B, Thiele J, Mekori YA, Henz BM. Expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL in cutaneous and bone marrow lesions of mastocytosis. The American journal of pathology. 2003 Sep:163(3):819-26 [PubMed PMID: 12937123]

Brockow K, Akin C, Huber M, Metcalfe DD. IL-6 levels predict disease variant and extent of organ involvement in patients with mastocytosis. Clinical immunology (Orlando, Fla.). 2005 May:115(2):216-23 [PubMed PMID: 15885646]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSławińska M, Kaszuba A, Lange M, Nowicki RJ, Sobjanek M, Errichetti E. Dermoscopic Features of Different Forms of Cutaneous Mastocytosis: A Systematic Review. Journal of clinical medicine. 2022 Aug 9:11(16):. doi: 10.3390/jcm11164649. Epub 2022 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 36012900]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMarrero Alemán G, El Habr C, Islas Norris D, Montenegro Dámaso T, Borrego L, Sangueza OP. Cutaneous Mastocytosis With Atypical Mast Cells in a 7-Year-Old Girl. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2017 Apr:39(4):310-312. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000768. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28328617]

Pardanani A. Systemic mastocytosis in adults: 2017 update on diagnosis, risk stratification and management. American journal of hematology. 2016 Nov:91(11):1146-1159. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24553. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27762455]

Lange M, Niedoszytko M, Renke J, Gleń J, Nedoszytko B. Clinical aspects of paediatric mastocytosis: a review of 101 cases. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2013 Jan:27(1):97-102. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04365.x. Epub 2011 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 22126331]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNirmal B, Krishnaram AS, Muthu Y, Rajagopal P. Dermatoscopy of Urticaria Pigmentosa with and without Darier's Sign in Skin of Colour. Indian dermatology online journal. 2019 Sep-Oct:10(5):577-579. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_501_18. Epub 2019 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 31544081]

Verma KK, Bhat R, Singh MK. Bullous mastocytosis treated with oral betamethasone therapy. Indian journal of pediatrics. 2004 Mar:71(3):261-3 [PubMed PMID: 15080414]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKayiran MA, Akdeniz N. Diagnosis and treatment of urticaria in primary care. Northern clinics of Istanbul. 2019:6(1):93-99. doi: 10.14744/nci.2018.75010. Epub 2019 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 31180381]

Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, van der Heide S, Oude Elberink JN, Kluin-Nelemans JC, Dubois AE. Mastocytosis and adverse reactions to biogenic amines and histamine-releasing foods: what is the evidence? The Netherlands journal of medicine. 2005 Jul-Aug:63(7):244-9 [PubMed PMID: 16093574]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHoffmann KM, Moser A, Lohse P, Winkler A, Binder B, Sovinz P, Lackner H, Schwinger W, Benesch M, Urban C. Successful treatment of progressive cutaneous mastocytosis with imatinib in a 2-year-old boy carrying a somatic KIT mutation. Blood. 2008 Sep 1:112(5):1655-7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147785. Epub 2008 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 18567837]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCavazos A, Subrt P, Tschen JA. Delayed diagnosis of adult-onset mastocytosis. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 2022:35(5):717-718. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2022.2081914. Epub 2022 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 35991727]

Popadic S, Lalosevic J, Lekic B, Gajić-Veljic M, Bonaci-Nikolic B, Nikolic M. Mastocytosis in children: a single-center long-term follow-up study. International journal of dermatology. 2023 May:62(5):616-620. doi: 10.1111/ijd.16612. Epub 2023 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 36807903]