Introduction

Diverticulitis has increased in incidence over the past few decades, becoming a major healthcare burden for Western countries.[1] In the United States, acute diverticulitis results in nearly 200,000 hospital admissions and $2.2 billion in health care costs annually.[2] Although the prevalence of the disease increases with age, younger adults may also develop the diverticular disease. In fact, for some time, it was thought that younger and male patients were more likely to experience a more aggressive form of diverticulitis with an increased complication rate and higher recurrence.[3] However, recent studies have challenged this concept. Environmental and genetic risk factors result in diverticular disease development, although good quality evidence for many of these factors remains insufficient. Most cases of diverticulitis undergo successful management in the outpatient setting with oral antibiotics and temporary dietary restrictions. The decision to perform elective sigmoid colectomy in patients who recover from uncomplicated diverticulitis is controversial and requires case-by-case consideration. Surgical treatment is recommended in cases of complicated diverticulitis.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The diverticular disease starts with an out-pouching of the mucosa of the colonic wall. Inflammation at each mucosal out-pouching contributes to diverticulitis. The presumed mechanism of diverticulitis is an overgrowth of bacteria due to feces' obstruction of the diverticular base with micro-perforations. This theory has been challenged in recent years as some studies demonstrate that the resolution of uncomplicated diverticulitis may occur without antibiotics in selected cases.[4]

Epidemiology

Diverticulosis of the colon is common in western countries and increases with age. Over 50% of individuals over 60 have diverticulosis, and the incidence rises to 70% after 80 years.[5] Despite the significant prevalence of diverticulosis in the population, only 4% of individuals develop diverticulitis in their lifetime.[6] The distribution of the colonic diverticula varies depending on population demographics. In Western countries, diverticula are most common in the sigmoid colon, with a rate of 65%.[1] The right colon is more commonly involved in Asian populations. This difference was once attributed to daily dietary fiber, but epidemiologic studies have refuted this concept. These studies have analyzed Asian populations after relocation and changes in dietary habits, but there is no proof of any change in the diverticular pattern.[7] Although environmental factors play a significant role in diverticulosis development, studies on identical twins have identified a strong genetic predisposition.[8]

Multiple environmental risk factors have been postulated in the development of diverticular disease; however, many remain controversial. A 1970 study hypothesized that a diet high in fiber was protective against diverticular disease, but the evidence is conflicting.[9] For patients with a history of diverticulitis, The American Gastroenterology Association and the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons recommend a diet high in fiber. In this setting, increasing dietary fiber correlates with reducing the development of recurrent episodes of acute uncomplicated and complicated diverticulitis.[10] In the past, patients with diverticular disease were discouraged from eating nuts, seeds, and popcorn. Still, a recent study determined that these foods do not increase the risk of developing diverticulitis.[11] Red meat, particularly beef and lamb, has been associated with an increased risk of diverticulitis hospitalization. Obesity, smoking, and alcohol use are also associated with a higher incidence of diverticular disease.[12] Medications, including NSAIDs, aminosalicylates (ASA), and acetaminophen, seem to increase the risk of developing complicated diverticulitis. Current corticosteroid use doubles the risk of developing perforated diverticulitis.[13] There are also postulates regarding protective factors. Vigorous exercise, such as running, has shown a risk reduction of developing complicated diverticulitis by 25%. Light activity, such as walking, is less effective.[14] Statin medications appear to reduce the risk of perforated diverticulitis.[13] Maintaining a normal weight and eliminating smoking also decreases the risk of diverticular disease.

Pathophysiology

Despite the high prevalence of diverticulosis, the pathophysiology of the disease is not well understood. A colonic diverticulum is an out-pouching of the colonic mucosa through the weakest point in the colonic lumen, where the vasa recta penetrates the colonic wall to supply blood to the submucosa and mucosa. Patients with diverticulosis have increased intraluminal pressures during peristalsis.[4] High colonic intraluminal pressure associated with constipation and straining during defecation was once thought to be the initiating factor resulting in mucosal herniation through the colonic wall. However, this theory is currently under question.[8]

History and Physical

Most patients with diverticulosis are asymptomatic, and diverticula is commonly identified incidentally during colonoscopy or radiologic studies. Patients with acute diverticulitis may present with fever, left lower quadrant pain, and changes in bowel habits. Left lower abdominal pain is the most common presenting feature in 70% of patients. The character of pain is mainly described as crampy and may be associated with a change in bowel habits. Consequently, the presentation of diverticulitis may be confused with irritable bowel syndrome. Other symptoms of diverticulitis include nausea, vomiting, constipation, flatulence, and bloating. Acute presentation of diverticulitis may also be because of a complication, such as colonic abscess, intestinal perforation, and fistula formation. Laboratory findings include leukocytosis and possibly elevated inflammatory markers.[15] Those patients with complicated diverticulitis may present with signs of sepsis and physical findings consistent with peritonitis. Physical findings may include abdominal tenderness, abdominal distension, a tender mass in the abdomen, absent bowel sounds, and findings related to fistula formation. The presence of fecaluria and pneumaturia must alert the clinician to the possibility of a colovesical fistula.

Evaluation

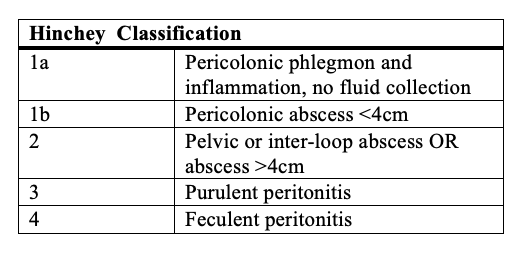

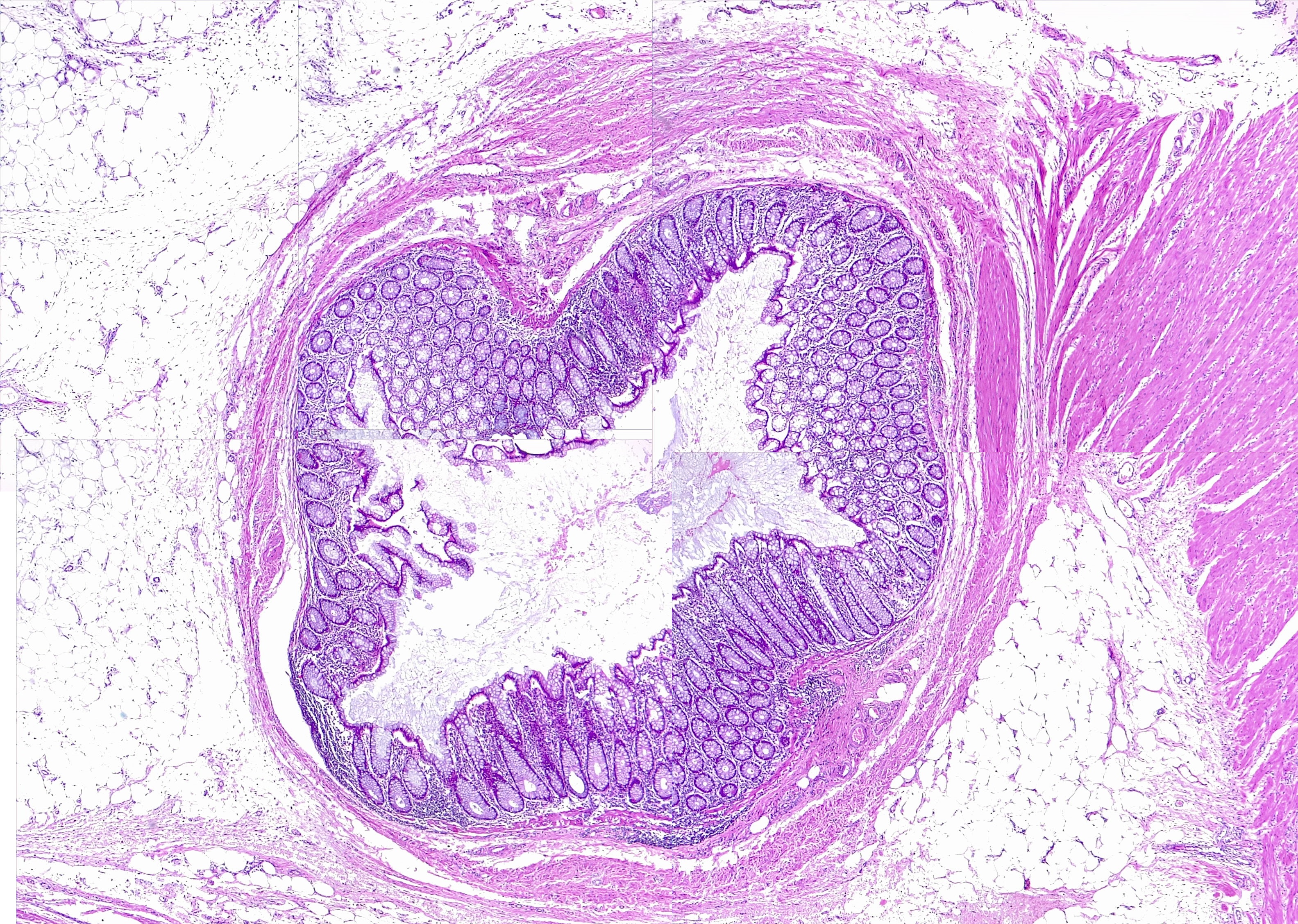

When the history, physical exam, and laboratory findings are consistent with the diagnosis of acute diverticulitis, confirmatory imaging studies are the next step (see Image. Colon, Diverticulum). Different imaging modalities, including ultrasound and barium enema, may be used to diagnose diverticular disease. However, a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast is the preferred modality. Its diagnostic accuracy is high, with a sensitivity of 98%.[16] assessment of renal function before the administration of intravenous contrast is imperative. Findings of colonic wall thickening and fat stranding are typical for diverticulitis. Signs of complicated disease, including fistula formation, abscesses, and intra-abdominal free air, are easily identifiable with scans.[17] The Hinchey classification system is useful in determining the disease's severity and allocating patients to different treatment algorithms (see Image. Hinchey Classification of Diverticulitis). Generally speaking, patients with Hinchey 1a and 1b diverticulitis are manageable by nonsurgical means. Patients with Hinchey 2 diverticulitis may require placement of a percutaneous drain followed by elective sigmoid colectomy. However, patients with Hinchey 3 and 4 require urgent surgical intervention. A urinalysis may reveal red or white blood cells, prompting suspicion of a colovesical fistula. In females of childbearing age who present with abdominal pain, a pregnancy test must be carried out to rule out an ectopic pregnancy.

Treatment / Management

The medical management of acute non-complicated diverticulitis includes oral or intravenous antibiotics, pain control, hydration, and restricted oral intake. Medical management of diverticulitis with antibiotics remains the standard of care. However, antibiotic choice, treatment duration, and administration route remain controversial.[18] Most cases of uncomplicated diverticulitis are successfully treatable in the outpatient setting. Oral antibiotics, such as ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, or amoxicillin-clavulanate, are prescribed for 7 to 10 days, with recommendations to minimize oral intake until the pain resolves.[15] Patients who are febrile, immunosuppressed, unable to stay hydrated, or those with multiple medical comorbidities require admission to the hospital for treatment with parenteral antibiotics. As symptoms improve, the diet advances, and patients are started on oral antibiotics. Any patient failing to improve on parenteral antibiotics or deteriorates during therapy should undergo repeat evaluation with CT imaging to rule out evolving complications.[15] After acute episode resolution of diverticulitis, a colonoscopy is recommended 6 to 8 weeks later, particularly if the patient has not had a colonoscopy in the past 2 to 3 years.[15] (B3)

Historically, elective sigmoid colectomy used to be performed after the second bout of uncomplicated diverticulitis. However, more recent evidence has disproved the benefit of this approach. Firstly, the recurrence rate of uncomplicated diverticulitis is lower than previously estimated, ranging from 13 to 23%. Secondly, the incidence of complicated recurrent episodes that may require a stoma is also low, at approximately 6%. Therefore, current recommendations emphasize that selection criteria for elective surgery should be individualized according to the number, severity, and frequency of diverticulitis episodes, persistent symptomatology after an episode of diverticulitis, and the patient's immunologic status. These criteria merit consideration in terms of the patient’s age, comorbidities, and social history. Finally, routine sigmoid colectomy in patients younger than 50 is no longer the recommended therapeutic path.[10] Younger patients should receive the same treatment as their older counterparts. Regardless of the indication and technique used (open, laparoscopic, or robotic) when performing an elective sigmoid colectomy for diverticulitis, it requires removing the entire sigmoid colon, the proximal and distal anastomotic sites must appear healthy and well-perfused, and the anastomosis performed without tension.

Approximately 1% of patients with an acute episode of diverticulitis require surgical intervention during that episode.[19] Patients presenting with signs of peritonitis are candidates for emergent surgery. When intraoperative findings confirm perforated diverticulitis, the traditional operation is a Hartmann procedure, which includes resection of the sigmoid colon, preservation of the rectum in the form of a rectal pouch, and creation of an end colostomy. This procedure eliminates the risk of an anastomotic leak; patients are considered for colostomy reversal in 3 to 6 months. However, due to old age and associated comorbidities, nearly 30% of patients undergoing a Hartmann procedure never have colostomy reversal.[15]

A second option for patients with Hinchey 3 and 4 diseases is a primary colorectal anastomosis with a proximal diverting ileostomy. Initial retrospective evaluation of this surgical modality shows a decreased overall mortality after performing a primary anastomosis. However, randomized controlled studies comparing a Hartmann procedure to the primary anastomosis with proximal diversion are not yet available.[20] An old approach, no longer considered in the surgical management of complicated diverticulitis, consisted of leaving the inflamed or perforated sigmoid colon in situ and placing a proximal stoma with the plan of second and then third-stage procedures. Acute colonic diverticulitis should be managed in a stepwise manner as follows:(A1)

- Patients who meet the following criteria should be admitted for inpatient management.[21]

- Presence of evidence suggestive of complicated diverticulitis, including:

- Frank perforation

- Abscess formation in a symptomatic patient

- Bowel obstruction

- Complicated colonic diverticula with a fistula formation

- Evidence of sepsis or systemic inflammatory response syndrome suggestive by equal or more than 2 of the following indexes;

- Temperature of greater than 38 C or less than 36

- Heart rate of greater than 90 beats per minute

- Respiratory rate of greater than 20 breaths per minute

- WBC of greater than 12,000 cells/mm3 or less than 4,000 cells/mm3

- C-reactive protein level of greater than 15 mg/dl[21]

- Physical examination suggestive of diffuse, non-localized peritonitis

- Evidence of micro-perforations in the imaging measures, including the presence of few extramural colonic micro-bubbles

- Advanced age: older than 70

- Remarkable comorbidities, including but not limited to:

- Diabetes mellitus with end-organ damage (eg, presence of retinopathy, microangiopathy, and nephropathy)

- Recent cardiovascular events, including acute myocardial infarction

- Immunocompromised status

- Oral intake intolerance

- Presence of evidence suggestive of complicated diverticulitis, including:

Inpatient management should be initiated with intravenous antibiotics, hydration, pain control with intravenous medications, and complete bowel rest. However, some centers have also investigated the dietary limitations of a liquid diet.[21] In patients with signs and symptoms of acute colonic diverticulitis who do not meet the criteria to be admitted for inpatient management, outpatient treatment with pain control and a liquid diet should be triggered. However, the response to the conservative outpatient treatment should be re-evaluated within the first 72 hours. Those without improvement evidence should be admitted for inpatient management. On the contrary, the responders to conservative management should be approached with diet advancement and clinical reassessment weekly. An elective colonoscopy should be scheduled if all the symptoms are resolved within 6 weeks after the index episode.[21][22] It should be noted that even in patients with normal colonoscopies, surgical referral for further evaluation should be considered in the following circumstances: 1. immunocompromised patients and 2. complicated episodes of diverticulitis.[22] Otherwise, a high-fiber diet is recommended.

- If the patient does not meet any of the mentioned criteria, outpatient treatment with pain control and a liquid diet should be initiated. Still, clinical improvement should be evaluated in 2 or 3 days.

- In the absence of clinical improvement within 3 days, inpatient management should be initiated with intravenous antibiotics, hydration, pain control with intravenous medications, and complete bowel rest. However, some centers have also investigated the dietary limitations of a liquid diet.[21]

- Frank perforation, obstruction, or fistula formation should be evaluated during inpatient management. In the presence of any of these complications, surgical referral should be considered.

- In the absence of the mentioned complications, the next step is to evaluate the presence of a drainable abscess equal to or greater than 4 cm, which should be drained percutaneously.

- If the abscess is less than 4 cm, the clinical improvement within the first 3 days should be examined.

Differential Diagnosis

Diverticulitis can occur anywhere in the colon; the presentation may vary according to the site involved. For instance, diverticulitis in the right colon may present similarly to acute appendicitis. Similarly, diverticula in the transverse colon may appear as peptic ulcer disease, pancreatitis, or cholecystitis. Therefore, the list of differential diagnoses is extensive as follows:

- Acute gastritis

- Acute pancreatitis

- Acute appendicitis

- Acute cholecystitis

- Acute pyelonephritis

- Cholangitis

- Mesenteric ischemia

- Constipation

- Irritable bowel disease

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Ovarian cyst

- Ectopic pregnancy

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

Recent studies have demonstrated the resolution of uncomplicated diverticulitis without antibiotics in very well-selected patients. Patients with peritonitis, perforation, signs of sepsis, and hemodynamic instability were excluded. Although some patients did develop perforations or abscesses, the risk was considered low. There was no difference in primary outcomes between the group treated with antibiotics and those without antibiotic therapy.[18] The evidence for this unique treatment approach is preliminary, and further study is needed. Traditionally, patients with generalized peritonitis from perforated diverticulitis undergo a Hartman procedure or primary anastomosis with a proximal diverting stoma. Researchers have studied laparoscopic peritoneal lavage as an alternative to the standard surgical treatment of perforated diverticulitis.[23] Other studies have not duplicated the initial results, so this treatment remains controversial.

Prognosis

The prognosis of the patients depends on the severity of the illness and the presence of complications. Immunocompromised patients have higher morbidity and mortality as a result of sigmoid diverticulitis.[24] After the first incident of acute diverticulitis, the 5-year recurrence rate is approximately 20%.[25] Several studies have demonstrated the significant link between increased BMI and the risk of developing diverticulitis.[26]

Complications

Many complications can occur in a patient with diverticulitis, which can be more severe in certain cases, such as in immunocompromised patients. For instance, those infected with HIV or those on immunosuppressants are more likely to develop perforation.[27] The following are the possible complications of diverticulitis:

- Abscess formation (most common)

- Intestinal perforation

- Intestinal fistula

- Intestinal obstruction

- Generalized peritonitis

- Stricture disease

- Sepsis

Consultations

Interprofessional teams must deliver the present management of diverticulitis in the context of the most recent scientific evidence. These teams can include gastroenterologists, internists, general surgeons, colostomy care nurses, gastroenterology specialty-trained nurses, and pharmacists, working collaboratively to bring about optimal patient care and outcomes.

Deterrence and Patient Education

To help prevent a recurrence of their condition, patients are advised to consume a high-fiber diet, drink 6 to 8 glasses of water daily, exercise, monitor any changes in their bowel movements, and use a stool softener if they become constipated.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The incidence of diverticulitis increases in all age groups, placing a substantial burden on the healthcare system. The interprofessional healthcare team, consisting of primary care physicians, NPs, PAs, gastroenterologists, nurses, pharmacists, and dietitians, must educate the public and patients that obesity, inactivity, and a poor diet contribute significantly to epidemiologic factors. Pharmacists perform medication reconciliation when drug therapy is part of the treatment; they can also counsel patients on their medications, assist with dosing, and report any concerns to the prescribing clinician. Nurses coordinate activities between the various clinicians and specialists on the case and offer patients, counsel, on their condition. They are also responsible for assisting during surgery and monitoring patients post-procedure.

A positive paradigm change in diverticulitis treatment has resulted in the widespread use of outpatient management for non-complicated diverticulitis. However, many patients with a history of non-complicated diverticulitis are improperly managed empirically with antibiotics every time they call their clinician’s office with abdominal pain. This misuse of antibiotics must be corrected. A colostomy nurse should educate patients undergoing surgery on stoma care. All care team members must utilize meticulous record-keeping so that every caregiver on the case can access the same updated patient information. Better and more sophisticated imaging modalities have allowed us to accurately classify disease severity and allocate different patients to more effective treatment algorithms. The current emphasis on individualizing the need for elective sigmoid colectomy after resolving non-complicated diverticulitis results in fewer unnecessary operations and better outcomes.

Media

References

Munie ST, Nalamati SPM. Epidemiology and Pathophysiology of Diverticular Disease. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2018 Jul:31(4):209-213. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1607464. Epub 2018 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 29942208]

Peery AF, Crockett SD, Barritt AS, Dellon ES, Eluri S, Gangarosa LM, Jensen ET, Lund JL, Pasricha S, Runge T, Schmidt M, Shaheen NJ, Sandler RS. Burden of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015 Dec:149(7):1731-1741.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.045. Epub 2015 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 26327134]

Lahat A, Menachem Y, Avidan B, Yanai H, Sakhnini E, Bardan E, Bar-Meir S. Diverticulitis in the young patient--is it different ? World journal of gastroenterology. 2006 May 14:12(18):2932-5 [PubMed PMID: 16718822]

Schieffer KM,Kline BP,Yochum GS,Koltun WA, Pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Expert review of gastroenterology [PubMed PMID: 29846097]

Everhart JE, Ruhl CE. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States part II: lower gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology. 2009 Mar:136(3):741-54. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.015. Epub 2009 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 19166855]

Shahedi K, Fuller G, Bolus R, Cohen E, Vu M, Shah R, Agarwal N, Kaneshiro M, Atia M, Sheen V, Kurzbard N, van Oijen MG, Yen L, Hodgkins P, Erder MH, Spiegel B. Long-term risk of acute diverticulitis among patients with incidental diverticulosis found during colonoscopy. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2013 Dec:11(12):1609-13. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.06.020. Epub 2013 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 23856358]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStrate LL. Lifestyle factors and the course of diverticular disease. Digestive diseases (Basel, Switzerland). 2012:30(1):35-45. doi: 10.1159/000335707. Epub 2012 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 22572683]

Rezapour M, Ali S, Stollman N. Diverticular Disease: An Update on Pathogenesis and Management. Gut and liver. 2018 Mar 15:12(2):125-132. doi: 10.5009/gnl16552. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28494576]

Painter NS,Burkitt DP, Diverticular disease of the colon: a deficiency disease of Western civilization. British medical journal. 1971 May 22; [PubMed PMID: 4930390]

Feingold D, Steele SR, Lee S, Kaiser A, Boushey R, Buie WD, Rafferty JF. Practice parameters for the treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2014 Mar:57(3):284-94. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000075. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24509449]

Strate LL, Liu YL, Syngal S, Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL. Nut, corn, and popcorn consumption and the incidence of diverticular disease. JAMA. 2008 Aug 27:300(8):907-14. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.907. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18728264]

Manousos O, Day NE, Tzonou A, Papadimitriou C, Kapetanakis A, Polychronopoulou-Trichopoulou A, Trichopoulos D. Diet and other factors in the aetiology of diverticulosis: an epidemiological study in Greece. Gut. 1985 Jun:26(6):544-9 [PubMed PMID: 3924745]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHumes DJ, Fleming KM, Spiller RC, West J. Concurrent drug use and the risk of perforated colonic diverticular disease: a population-based case-control study. Gut. 2011 Feb:60(2):219-24. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.217281. Epub 2010 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 20940283]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBöhm SK, Kruis W. Lifestyle and other risk factors for diverticulitis. Minerva gastroenterologica e dietologica. 2017 Jun:63(2):110-118. doi: 10.23736/S1121-421X.17.02371-6. Epub 2017 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 28150481]

Young-Fadok TM. Diverticulitis. The New England journal of medicine. 2018 Oct 25:379(17):1635-1642. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1800468. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30354951]

Laméris W, van Randen A, Bipat S, Bossuyt PM, Boermeester MA, Stoker J. Graded compression ultrasonography and computed tomography in acute colonic diverticulitis: meta-analysis of test accuracy. European radiology. 2008 Nov:18(11):2498-511. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1018-6. Epub 2008 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 18523784]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKandagatla PG, Stefanou AJ. Current Status of the Radiologic Assessment of Diverticular Disease. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2018 Jul:31(4):217-220. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1607466. Epub 2018 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 29942210]

Huston JM,Zuckerbraun BS,Moore LJ,Sanders JM,Duane TM, Antibiotics versus No Antibiotics for the Treatment of Acute Uncomplicated Diverticulitis: Review of the Evidence and Future Directions. Surgical infections. 2018 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 30204549]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZoog E, Giles WH, Maxwell RA. An Update on the Current Management of Perforated Diverticulitis. The American surgeon. 2017 Dec 1:83(12):1321-1328 [PubMed PMID: 29336748]

Shaban F, Carney K, McGarry K, Holtham S. Perforated diverticulitis: To anastomose or not to anastomose? A systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of surgery (London, England). 2018 Oct:58():11-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.08.009. Epub 2018 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 30165109]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHanna MH, Kaiser AM. Update on the management of sigmoid diverticulitis. World journal of gastroenterology. 2021 Mar 7:27(9):760-781. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i9.760. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33727769]

Peery AF, Shaukat A, Strate LL. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Medical Management of Colonic Diverticulitis: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2021 Feb:160(3):906-911.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.09.059. Epub 2020 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 33279517]

Angenete E, Bock D, Rosenberg J, Haglind E. Laparoscopic lavage is superior to colon resection for perforated purulent diverticulitis-a meta-analysis. International journal of colorectal disease. 2017 Feb:32(2):163-169. doi: 10.1007/s00384-016-2636-0. Epub 2016 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 27567926]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBrandl A, Kratzer T, Kafka-Ritsch R, Braunwarth E, Denecke C, Weiss S, Atanasov G, Sucher R, Biebl M, Aigner F, Pratschke J, Öllinger R. Diverticulitis in immunosuppressed patients: A fatal outcome requiring a new approach? Canadian journal of surgery. Journal canadien de chirurgie. 2016 Aug:59(4):254-61. doi: 10.1503/cjs.012915. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27240131]

Peery AF. Recent Advances in Diverticular Disease. Current gastroenterology reports. 2016 Jul:18(7):37. doi: 10.1007/s11894-016-0513-1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27241190]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStrate LL, Liu YL, Aldoori WH, Syngal S, Giovannucci EL. Obesity increases the risks of diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2009 Jan:136(1):115-122.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.025. Epub 2008 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 18996378]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJacobs DO, Clinical practice. Diverticulitis. The New England journal of medicine. 2007 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 18003962]