Introduction

Pulmonary emphysema, a progressive lung disease, is a form of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) has defined COPD as "a common, preventable, and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that is due to airway or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases."[1][2][3]

COPD is the third leading cause of death worldwide.[4] COPD encompasses patients with chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Although these conditions are identified as separate entities, most patients with COPD have features of both.

COPD often coexists with comorbidities that can impact the progression and management of the disease. Emphysema, specifically, is a pathological diagnosis that affects the air spaces distal to the terminal bronchiole. It is characterized by abnormal and permanent enlargement of lung air spaces, the destruction of the air space walls without fibrosis, and a loss of elasticity in the lung parenchyma.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

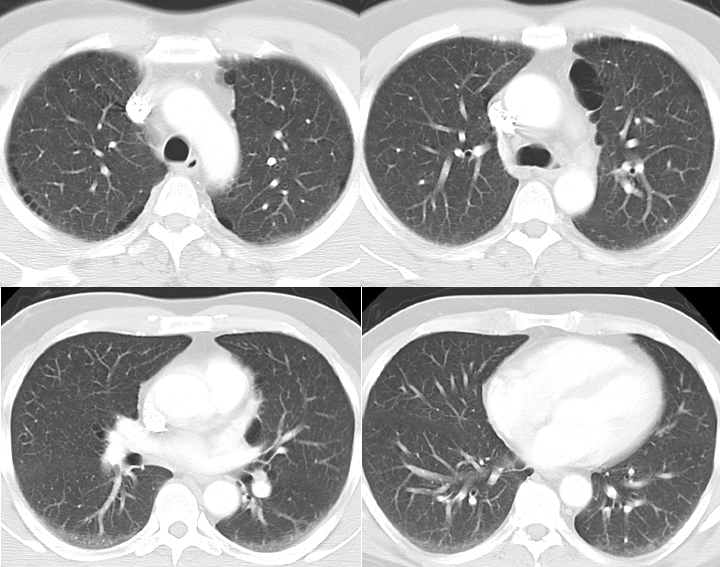

Emphysema is caused by chronic and significant exposure to noxious gases, with cigarette smoking being the most common cause. Between 80% to 90% of patients with COPD are identified as cigarette smokers. However, only 10% to 15% of smokers develop COPD (see Image. Emphysema). In smokers, the onset and severity of symptoms also depend on factors such as the intensity of smoking, the number of years of exposure, and baseline lung function. Typically, symptoms begin to appear after at least 20 pack-years of tobacco exposure.[5][6]

In addition to smoking, other environmental factors play a significant role in causing emphysema. In developing countries, biomass fuels and environmental pollutants such as sulfur dioxide and particulate matter are significant contributors, particularly affecting women and children.

The rise of electronic (e)-cigarettes has introduced another potential cause of emphysema. E-cigarettes can contain nicotine or be nicotine-free, but they often include numerous chemicals not found in traditional cigarettes. Multiple aerosols commonly found in e-cigarettes have been linked to airway hyperactivity, leading to concerns that inhaling these chemicals is harmful to the airways.[7] Since e-cigarettes have only recently entered the market, more long-term studies are needed to fully understand their impact on respiratory health.

A rare hereditary condition, alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency, can also lead to emphysema and liver abnormalities. This autosomal recessive disease accounts for only 1% to 2% of COPD cases. It is a known risk factor for panacinar bibasilar emphysema, which can present early in life.

Other contributing factors include passive smoking, recurrent lung infections, and allergies. Furthermore, low birth weight in newborns has been linked to a higher risk of developing COPD later in life.

Epidemiology

Emphysema, as part of COPD, affects a large number of people worldwide. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study in 2016, there were an estimated 251 million cases of COPD globally. Approximately 90% of COPD-related deaths occur in low and middle-income countries.[8][9] In 2019, COPD was the third leading cause of death worldwide, responsible for 3.23 million deaths.

In the US, the prevalence of emphysema is estimated to be around 14 million cases. Among white male smokers, 14% are affected, while 3% of white male nonsmokers develop the disease. The prevalence is slightly lower for white female smokers and African Americans, although these groups tend to develop emphysema after less exposure compared to other patient populations.

The incidence of emphysema is slowly increasing, primarily due to the rise in cigarette smoking and environmental pollution. Another contributing factor is the decreasing mortality rate from other causes, such as cardiovascular and infectious diseases, leading to a higher likelihood of living with COPD.

Genetic factors also play a significant role in determining susceptibility to airflow limitation in patients. Emphysema severity is notably higher in individuals with coal worker pneumoconiosis, regardless of their smoking status.

Pathophysiology

The clinical manifestations of emphysema arise from damage to the airways distal to the terminal bronchiole, including the respiratory bronchioles, alveolar sacs, alveolar ducts, and alveoli, collectively known as the acinus. In emphysema, there is abnormal permanent dilatation of the airspaces and destruction of their walls due to the proteinase activity. This dilatation decreases the alveolar and capillary surface area, impairing gas exchange. The specific part of the acinus affected determines the subtype of emphysema. Emphysema can be pathologically subdivided into the following types:

- Centrilobular (proximal acinar) emphysema is the most common type, typically associated with smoking. It can also be observed in individuals with coal workers' pneumoconiosis.

- Panacinar emphysema is most commonly associated with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

- Paraseptal (distal acinar) emphysema may occur alone or in combination with the other 2 types. When it occurs independently, it is often associated with spontaneous pneumothorax in young adults (see Image. CT Scan COPD, Paraseptal Emphysema).

After prolonged exposure to harmful smoke, inflammatory cells such as macrophages, neutrophils, and T lymphocytes are recruited, playing a crucial role in the development of emphysema. The process begins with macrophage activation, which releases neutrophil chemotactic factors like leukotriene B4 and interleukin-8. As neutrophils are recruited, they and macrophages release various proteinases that contribute to mucus hypersecretion.

Elastin, a crucial extracellular matrix component, helps maintain the integrity of the lung parenchyma and small airways. An imbalance between elastase and anti-elastase imbalance increases susceptibility to lung destruction, resulting in airspace enlargement. Cathepsins and neutrophil-derived proteases, such as elastase and proteinase, degrade elastin, damaging the connective tissue of the lung parenchyma.

Cytotoxic T cells also contribute to alveolar wall destruction by releasing TNF-a and perforins, which target and destroy epithelial cells. Cigarette smoking exacerbates mucus hypersecretion, promoting the release of neutrophilic proteolytic enzymes and inhibiting antiproteolytic enzymes and alveolar macrophages. In some cases, genetic polymorphisms result in insufficient antiprotease production in smokers, further accelerating the development of emphysema.

Lung parenchyma produces alpha-1 antitrypsin, an enzyme that inhibits trypsinize and neutrophil elastase, protecting the lung tissue from enzymatic damage. A deficiency in alpha-1 antitrypsin compromises these protective mechanisms, increasing the risk of developing panacinar emphysema.

History and Physical

Most patients with emphysema present with vague symptoms, including chronic shortness of breath and a cough, which may be accompanied by sputum production. As the disease progresses, these symptoms become more pronounced. Initially, patients may experience exertional dyspnea, especially during physical activity such as arm work at or above shoulder level. Over time, the dyspnea worsens, eventually occurring with simple daily activities and even at rest.

Some patients may also experience wheezing due to airflow obstruction. As COPD progresses, patients often lose significant body weight, which is attributed to systemic inflammation and increased energy expenditure required for breathing.

Additionally, COPD is characterized by frequent intermittent exacerbations as airway obstruction worsens. These exacerbations typically present with increased shortness of breath, more severe coughing, and increased sputum production. Infections or environmental factors often trigger them.

A detailed smoking history is crucial when evaluating a patient with emphysema. It is essential to document the age at which the person started smoking and calculate the total pack years. If the patient has quit smoking, knowing how many years have passed since their last cigarette is equally significant. Additionally, a history of environmental and occupational exposure, as well as a family history of chronic respiratory conditions and COPD, is essential.

In the early stages of emphysema, the physical examination may appear normal. Patients with emphysema are often called “pink puffers,” meaning they tend to be cachectic and noncyanotic. A characteristic feature is expiration through pursed lips, which increases airway pressure and helps prevent airway collapse during breathing. The use of accessory respiratory muscles indicates advanced disease.

Clubbing of the digits is not commonly associated with COPD. However, patients may have other comorbidities. Current smokers may present with an odor of smoke and nicotine staining on their hands and fingernails.

In the early stages, percussion findings may be normal. As the disease progresses and airway obstruction increases, physical examination findings may range from prolonged expiration or wheezes during forced exhalation to increased resonance, indicating hyperinflation. On auscultation, distant breath sounds, wheezes, crackles at the lung bases, or distant heart sounds may be heard.

Evaluation

Emphysema is a pathological diagnosis, and routine laboratory and radiographic studies are not typically indicated. The mainstay of diagnosis is pulmonary function testing (PFT), particularly spirometry. In cases of abnormal values, a postbronchodilator test may be performed. COPD is either partially reversible or irreversible with a bronchodilator, and postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in the first second over forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC )of less than 0.07 is diagnostic.[10][11][12][13]

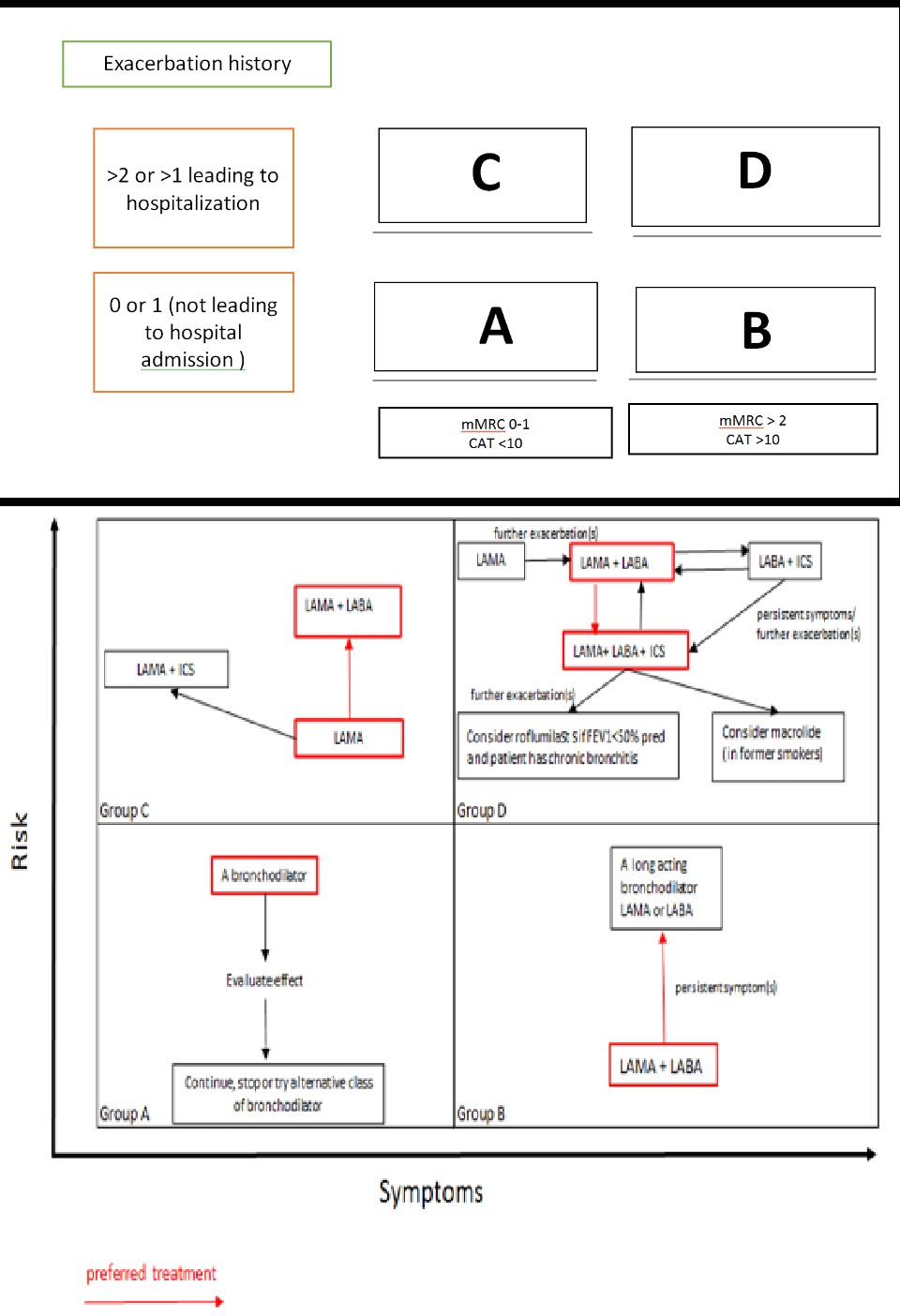

GOLD staging based on the severity of airflow limitation is as follows:

- Mild: FEV1 ≥80% predicted

- Moderate: FEV1 <80% predicted

- Severe: FEV1 <50% predicted

- Very severe: FEV1 <30% predicted

Lung volume measurements in emphysema reveal increased residual volume and total lung capacity, indicating air trapping. The diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide is reduced due to the destruction of the alveolar-capillary pulmonary membrane caused by emphysema.

A chest X-ray is typically not diagnostic in mild cases but may be helpful if emphysema is severe. It is usually the first step in evaluating suspecting COPD to rule out other causes. In emphysema, the destruction of alveoli and air trapping causes lung hyperinflation, flattening of the diaphragm, and the heart appearing elongated and tubular (see Image. X-ray, COPD, Subtle Paraseptal Emphysema).

Arterial blood gases are usually not required for mild to moderate COPD cases. However, they are indicated when oxygen saturation drops below 92% or if an assessment of hypercapnia is needed in cases of severe airflow obstruction.

Young individuals presenting with symptoms of emphysema should be tested for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Early detection can guide treatment and help prevent further lung damage.

Treatment / Management

There is no definitive treatment for emphysema that can alter the underlying disease process. However, modifying risk factors and managing symptoms have been shown to slow disease progression and improve quality of life effectively.[14][15][16] Based on the severity of symptoms and frequency of exacerbations, COPD can be classified into 4 GOLD stages, with treatment tailored accordingly. (B3)

Medical Therapy

Medical therapy includes using bronchodilators alone or with anti-inflammatory medications such as corticosteroids and phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors. These treatments help reduce airway inflammation, improve airflow, and alleviate symptoms, enhancing overall lung function and quality of life for patients.

Bronchodilator

The primary mechanisms of action for bronchodilators in COPD management fall into 2 categories: β 2 -agonists and anticholinergic medications. These are first-line drugs for COPD and are administered via inhalation. Both bronchodilators improve FEV1 by altering airway smooth muscle tone, improving exercise tolerance. Bronchodilators are prescribed regularly to prevent and reduce symptoms, exacerbations, and hospitalizations.

Short-acting β 2 -agonists (SABA) and short-acting muscarinic antagonists (SAMA) are commonly used as needed to manage intermittent dyspnea. In cases where dyspnea increases or becomes more frequent, long-acting β 2 -agonists (LABA) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) are prescribed. If symptoms persist using a single bronchodilator, a second bronchodilator can be added.

β 2 -agonists work by relaxing smooth airway muscles. SABAs, like albuterol, can be used with or without anticholinergics and are a mainstay in treating COPD exacerbations. LABAs include drugs like formoterol, salmeterol, indacaterol, olodaterol, vilanterol. Possible side effects of β 2 -agonists include arrhythmias, tremors, and hypokalemia. Caution should be taken in patients with heart failure, as tachycardia can precipitate cardiac issues.

Anticholinergics, on the other hand, work by inhibiting acetyl-choline-induced bronchoconstriction. SAMAs include ipratropium and oxitropium, while LAMAs, such as tiotropium, can be administered once daily for long-term symptom control.

Inhaled corticosteroid

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are used as a step-up treatment approach to bronchodilators. ICS medications include beclomethasone, budesonide, and fluticasone. While these medications can be effective, they may cause side effects such as local infection, cough, and pneumonia.

Oral systemic corticosteroids are typically used for all patients experiencing COPD exacerbation. However, they are generally avoided in stable patients due to the increased risk of adverse effects.

Oral phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors

Roflumilast is an oral phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor that helps reduce inflammation. It can be added to the treatment regimen for patients with severe airflow obstruction who do not show improvement with other medications.

Triple inhaled therapy

The FDA recently approved triple inhaled therapy consisting of a LABA, a LAMA, and an ICS. This combination is administered once daily.

Intravenous alpha1 antitrypsin augmentation therapy

Patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency may undergo augmentation therapy. However, the high cost and limited availability are significant barriers to this treatment.

Supportive Therapy

Supportive therapy for emphysema includes oxygen therapy, ventilatory support, pulmonary rehabilitation, and palliative care. These interventions aim to improve quality of life, enhance functional capacity, and manage symptoms in advanced stages of the disease.

Routine supplemental oxygen does not improve the quality of life or clinical outcomes in stable patients with emphysema. However, continuous long-term therapy, defined as more than 15 hours per day, is recommended for patients with COPD who have a PaO2 of less than 55 mmHg (or an oxygen saturation of less than 88%) or a PaO2 of less than 59 mm Hg in the presence of cor pulmonale. Oxygen therapy has been shown to increase survival in patients with severe resting hypoxemia.

Intermittent oxygen therapy can be beneficial for those who become desaturated during exercise. The primary goal is to maintain an oxygen saturation above 90%. In COPD, a significant cause of hypoxemia is ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) mismatch, especially in areas of low V/Q ratios. Hypoxic vasoconstriction in the pulmonary arteries helps improve overall gas exchange efficiency. Supplemental oxygen allows more oxygen to reach the alveoli, preventing this vasoconstriction, increasing perfusion, and improving gas exchange, alleviating hypoxemia.

Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) reduces morbidity and mortality in patients with acute respiratory failure. It should be the first mode of ventilation attempted in patients with COPD exacerbation and respiratory failure, provided there are no absolute contraindications. NPPV improves gas exchange, decreases hospitalization duration, reduces breathing work, enhances V/Q matching, and improves survival rates.

If NPPV fails in the hospital setting, the patient should be intubated and placed on mechanical ventilation. Early intervention with NPPV can prevent the need for invasive procedures and reduce associated complications.

Pulmonary rehabilitation is recommended for patients with severe symptoms and multiple exacerbations, particularly those in GOLD stages B, C, and D. This therapy reduces dyspnea and hospitalizations, helping improve quality of life. Although palliative care is available from the time a person is diagnosed with COPD, it is typically recommended for patients in GOLD stage D as an additional layer of support alongside the ongoing treatment plan. The goal is to provide the best quality of life possible.

Palliative care helps assess and manage symptoms, aids patients in understanding their illness, and facilitates discussions about care goals, advance care, and end-of-life planning. Advance care planning involves communication between patients, their families, and physicians to help patients make informed decisions about their treatment preferences. An essential component of palliative care is reassuring patients with a clear plan to manage dyspnea in advanced disease, as well as addressing depression and anxiety. These symptoms can be managed with low-dose opioids, lifestyle modifications, and relaxation techniques.

Many patients underestimate the severity of their disease, so it is crucial to identify the right time for transitioning care and discussing advanced care early in the disease process. Additionally, it is essential to explore the patient's preferences for where they want to spend their final days, whether at home or in a hospital, and to help provide as much comfort as possible.

Interventional Therapy

Interventional therapy for emphysema includes minimally invasive procedures aimed at improving lung function and alleviating symptoms in patients with advanced disease. These therapies, such as bronchoscopic interventions and lung volume reduction surgery, are typically considered when medical treatments are insufficient to control symptoms.

- Lung volume reduction surgery reduces hyperinflation and improves elastic recoil.

- Lung transplantation is considered when FEV1 or DLCO drops below 20%.

Additional Interventions

Additionally, interventions for emphysema focus on both reducing risk factors and managing symptoms. Identifying and reducing exposure to risk factors is critical, with smoking cessation counseling being the most important intervention to slow disease progression. Reducing exposure to open cooking fires and promoting efficient ventilation in living spaces also benefit patients.

For those with severe COPD symptoms unresponsive to medical therapy, daily oral opioids can be considered. Nutritional supplementation is recommended for patients with malnutrition to help maintain strength and improve overall health. Vaccination is essential in preventing respiratory infections, with the pneumococcal 23-valent vaccine given every 5 years for patients older than 65 or those with other cardiopulmonary conditions and the influenza vaccine recommended annually for all patients with COPD.

Counseling on using metered-dose inhalers can lower readmission rates, ensuring patients understand how to use their medications effectively. Lastly, exercise is encouraged for all COPD patients to help maintain mobility, improve lung function, and enhance overall well-being.

Management of a Patient with COPD Exacerbation

Beta-agonists and anticholinergics can be used simultaneously in the management of emphysema. They are initially administered through nebulizers and later switched to metered-dose inhalers. Systemic corticosteroids, whether intravenous or oral, have been shown to hasten recovery and reduce hospital stays in patients experiencing exacerbations.

Antibiotics are also beneficial, especially when a cough productive of purulent sputum is present. Effective options include second-generation macrolides, extended-spectrum fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, and amoxicillin-clavulanate.

NPPV can be helpful for patients who can protect their airways and do not have significant acid-base disorder on arterial blood gas (ABG) tests. However, many patients with end-stage COPD experiencing exacerbations may require intubation and mechanical ventilation. It is critical to monitor ventilated patients for the development of auto-positive end-expiratory pressure (auto-PEEP) and its related complications.

Prevention

Preventing emphysema primarily involves smoking cessation, as quitting tobacco significantly reduces the risk of developing the disease. Vaccinating against Pneumococcus and Haemophilus influenzae can help protect individuals from respiratory infections that may exacerbate lung damage.[17][18](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

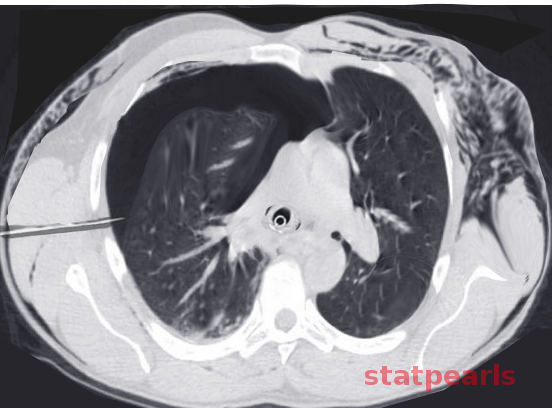

The differential diagnosis of emphysema is crucial due to its presentation with nonspecific symptoms, making it challenging to distinguish from other respiratory conditions. A broad range of potential diagnoses must be considered, including conditions such as chronic bronchitis, asthma, interstitial lung disease, and heart failure (see Image. Subcutaneous Emphysema). The differential list includes the following:

- Chronic obstructive asthma

- Chronic bronchitis with normal spirometry

- Cystic fibrosis

- Bronchopulmonary mycosis

- Central airway obstruction

- Bronchiectasis

- Heart failure

- Tuberculosis

- Constrictive bronchiolitis

- Anemia

- Complications

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Cor pulmonale

- Chronic respiratory failure

- Spontaneous pneumothorax

Prognosis

Various prognostic indicators have been studied about the mortality and morbidity associated with emphysema. The following factors have been identified as significant in correlating with disease burden and prognosis:

- FEV1

- DLCO

- Blood gas measurements

- Body mass index

- Exercise capacity

- Clinical state

- Radiographic severity[19]

The coexistence of other illnesses significantly worsens the prognosis for patients with COPD. For example, individuals presenting with features of both asthma and COPD often experience a poorer quality of life and face higher mortality rates. Similarly, patients with emphysema who exhibit elevated serum alpha-1 antitrypsin levels are at increased mortality risks.[20] Frequently observed comorbid conditions include metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and bronchiectasis, all of which further complicate disease management and outcomes.[21]

A widely used tool for predicting prognosis in patients with COPD is the BODE index, which takes into account the following factors:

- Body mass index

- FEV (obstruction)

- Dyspnea

- Exercise capacity

Complications

Patients with emphysema are at risk of developing a range of complications, some of which can be life-threatening. Commonly encountered complications include:

- Respiratory insufficiency or failure

- Pneumonia

- Pneumothorax

- Chronic atelectasis

- Cor pulmonale

- Interstitial emphysema

- Recurrent respiratory tract infections

- Respiratory acidosis, hypoxia, and coma

Consultations

Internists, emergency physicians, pulmonary specialists, specialized nurses, respiratory therapists, and physician assistants all play vital roles in the comprehensive management of patients with emphysema. Consultation with a pulmonary specialist is particularly crucial in the following cases:

- Uncertain diagnosis

- Persistent symptoms despite initial medical therapy

- Frequent exacerbations despite medical management

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is diagnosed

- Presence of atypical presentation

- Alarming features such as hemoptysis, weight loss, or night sweats are observed

- Coexistence of asthma and COPD

- Other comorbid illnesses

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education is crucial for managing emphysema and improving quality of life. Patients should be informed about the nature of the disease, its primary causes—particularly smoking—and its impact on lung function. Emphasis should be placed on the importance of early detection and routine monitoring of lung health to slow disease progression and manage symptoms effectively.

Smoking cessation is vital for patients with emphysema, as it is the most effective method to slow disease progression. Patients should be provided with comprehensive resources and support to help them quit, including counseling and nicotine replacement therapies.

Patients should receive clear instructions on the purpose and proper use of their prescribed medications. Education should include guidance on recognizing when to use rescue inhalers and emphasizing the importance of adherence to prescribed therapies for optimal disease management.

Patients should also be educated on the importance of maintaining physical activity, nutrition, and measures to prevent infection. Additionally, they should learn to recognize signs and symptoms of exacerbations, such as worsening shortness of breath, increased cough, and changes in sputum production. Education should include when to seek prompt medical attention.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to keep in mind about emphysema are as follows:

- Medications for primary pulmonary hypertension are not recommended for patients with pulmonary hypertension secondary to COPD.

- Depression and anxiety are common in end-stage lung disease, and pharmacological agents can be used as needed.

- Long-term oral corticosteroids are not recommended for managing COPD.

- ICS alone is not recommended; combination treatment with LABA and LAMA is more effective in reducing exacerbations compared to monotherapy.

- A combination of SAMA and SABA improves symptoms and FEV-1.

- Theophylline has limited bronchodilator effects in stable COPD and is associated with modest symptomatic benefits.

- Assessment and appropriate management of comorbidities for patients with COPD significantly influence mortality and hospitalizations.

- Excessive correction of hypoxia in patients with longstanding COPD can lead to hypercapnia. This occurs due to the loss of compensatory vasoconstriction, ineffective gas exchange, and a diminished hypoxic drive for ventilation. Increased oxyhemoglobin also decreases carbon dioxide uptake due to the Haldane effect.

- The only interventions proven to decrease mortality in COPD are smoking cessation and continuous home oxygen therapy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of emphysema involves an interprofessional team, including a pulmonologist, internist, pharmacist, dietitian, social worker, respiratory therapist, primary care provider, and a thoracic surgeon. While there is no cure for emphysema, it is crucial to address the primary, such as educating the patient about the harms of smoking and ensuring they receive the annual influenza vaccine.

The outlook for most patients is guarded, with a poor quality of life characterized by frequent exacerbations and episodes of acute respiratory distress. Some patients may develop repeated pneumothoraces, which may require intervention from a thoracic surgeon. Several lung volume reduction procedures are available, but they carry high risks and potential complications, necessitating prolonged intensive care.

Pharmacists play a vital role in reviewing prescriptions, checking for interactions, and emphasizing the importance of medication compliance to patients and their families. Nurses are responsible for monitoring and educating patients and reporting any changes in their status to the healthcare team.[2][22]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Rustagi N, Singh S, Dutt N, Kuwal A, Chaudhry K, Shekhar S, Kirubakaran R. Efficacy and Safety of Stent, Valves, Vapour ablation, Coils and Sealant Therapies in Advanced Emphysema: A Meta-Analysis. Turkish thoracic journal. 2019 Jan 1:20(1):43-60. doi: 10.5152/TurkThoracJ.2018.18062. Epub 2019 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 30664426]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFernandez-Bussy S, Labarca G, Herth FJF. Bronchoscopic Lung Volume Reduction in Patients with Severe Emphysema. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine. 2018 Dec:39(6):685-692. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676774. Epub 2019 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 30641586]

Dunlap DG, Semaan R, Riley CM, Sciurba FC. Bronchoscopic device intervention in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2019 Mar:25(2):201-210. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000561. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30640188]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKahnert K, Jörres RA, Behr J, Welte T. The Diagnosis and Treatment of COPD and Its Comorbidities. Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 2023 Jun 23:120(25):434-444. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.m2023.027. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36794439]

Asri H, Zegmout A. [The two major complications of tobacco in a single image!]. The Pan African medical journal. 2018:30():252. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.30.252.16393. Epub 2018 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 30627313]

Thomson NC. Challenges in the management of asthma associated with smoking-induced airway diseases. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2018 Oct:19(14):1565-1579. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2018.1515912. Epub 2018 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 30196731]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTsai M, Byun MK, Shin J, Crotty Alexander LE. Effects of e-cigarettes and vaping devices on cardiac and pulmonary physiology. The Journal of physiology. 2020 Nov:598(22):5039-5062. doi: 10.1113/JP279754. Epub 2020 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 32975834]

Zhang H, Dong L, Kang YK, Lu Y, Wei HH, Huang J, Wang X, Huang K. Epidemiology of chronic airway disease: results from a cross-sectional survey in Beijing, China. Journal of thoracic disease. 2018 Nov:10(11):6168-6175. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.10.44. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30622788]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMouronte-Roibás C, Fernández-Villar A, Ruano-Raviña A, Ramos-Hernández C, Tilve-Gómez A, Rodríguez-Fernández P, Díaz ACC, Vázquez-Noguerol MG, Fernández-García S, Leiro-Fernández V. Influence of the type of emphysema in the relationship between COPD and lung cancer. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2018:13():3563-3570. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S178109. Epub 2018 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 30464438]

Harrison R, Knowles S, Doherty C. Surgical Emphysema in a Pediatric Tertiary Referral Center. Pediatric emergency care. 2020 Jan:36(1):e21-e24. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001725. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30672901]

Buttar BS, Bernstein M. The Importance of Early Identification of Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency. Cureus. 2018 Oct 25:10(10):e3494. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3494. Epub 2018 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 30648036]

Cheng T, Li Y, Pang S, Wan HY, Shi GC, Cheng QJ, Li QY, Pan ZL, Huang SG. Emphysema extent on computed tomography is a highly specific index in diagnosing persistent airflow limitation: a real-world study in China. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2019:14():13-26. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S157141. Epub 2018 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 30587958]

Bhatt SP, Bhakta NR, Wilson CG, Cooper CB, Barjaktarevic I, Bodduluri S, Kim YI, Eberlein M, Woodruff PG, Sciurba FC, Castaldi PJ, Han MK, Dransfield MT, Nakhmani A. New Spirometry Indices for Detecting Mild Airflow Obstruction. Scientific reports. 2018 Nov 30:8(1):17484. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35930-2. Epub 2018 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 30504791]

Campo MI, Pascau J, José Estépar RS. EMPHYSEMA QUANTIFICATION ON SIMULATED X-RAYS THROUGH DEEP LEARNING TECHNIQUES. Proceedings. IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging. 2018 Apr:2018():273-276. doi: 10.1109/ISBI.2018.8363572. Epub 2018 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 30450153]

Storre JH, Callegari J, Magnet FS, Schwarz SB, Duiverman ML, Wijkstra PJ, Windisch W. Home noninvasive ventilatory support for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: patient selection and perspectives. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2018:13():753-760. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S154718. Epub 2018 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 29535515]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePress VG, Cifu AS, White SR. Screening for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. JAMA. 2017 Nov 7:318(17):1702-1703. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.15782. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29114819]

Calverley PMA, Anderson JA, Brook RD, Crim C, Gallot N, Kilbride S, Martinez FJ, Yates J, Newby DE, Vestbo J, Wise R, Celli BR, SUMMIT (Study to Understand Mortality and Morbidity) Investigators. Fluticasone Furoate, Vilanterol, and Lung Function Decline in Patients with Moderate Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Heightened Cardiovascular Risk. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2018 Jan 1:197(1):47-55. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201610-2086OC. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28737971]

Wood-Baker RR, Gibson PG, Hannay M, Walters EH, Walters JA. Systemic corticosteroids for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2005 Jan 25:(1):CD001288 [PubMed PMID: 15674875]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHaruna A, Muro S, Nakano Y, Ohara T, Hoshino Y, Ogawa E, Hirai T, Niimi A, Nishimura K, Chin K, Mishima M. CT scan findings of emphysema predict mortality in COPD. Chest. 2010 Sep:138(3):635-40. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2836. Epub 2010 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 20382712]

Takei N, Suzuki M, Makita H, Konno S, Shimizu K, Kimura H, Kimura H, Nishimura M. Serum Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Levels and the Clinical Course of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2019:14():2885-2893. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S225365. Epub 2019 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 31849461]

Singh D, Agusti A, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, Celli BR, Criner GJ, Frith P, Halpin DMG, Han M, López Varela MV, Martinez F, Montes de Oca M, Papi A, Pavord ID, Roche N, Sin DD, Stockley R, Vestbo J, Wedzicha JA, Vogelmeier C. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: the GOLD science committee report 2019. The European respiratory journal. 2019 May:53(5):. pii: 1900164. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00164-2019. Epub 2019 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 30846476]

Oey I, Waller D. The role of the multidisciplinary emphysema team meeting in the provision of lung volume reduction. Journal of thoracic disease. 2018 Aug:10(Suppl 23):S2824-S2829. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.02.68. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30210837]