Debriefing the Interprofessional Team in Medical Simulation

Debriefing the Interprofessional Team in Medical Simulation

Introduction

Today, more than ever, effective inter-professional team communication, collaboration, and coordination in the care of patients with increasingly more complex disorders in the fast-paced, dynamic, evolving healthcare environment is paramount. Inter-professional teamwork is now a worldwide-recognized core inter-professional competency that all healthcare providers should acquire. Simulation-based training (SBT) is an excellent format for fostering the knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) needed for highly reliable team interaction by bringing together inter-professional learners in a nonthreatening environment in which they can practice addressing high risk, low-frequency situations without any risk to a patient.[1] By doing so, these inter-professional teams can internalize these KSAs to make them automatic in the actual clinical environment.

Although the high technology simulators and complex scenarios of SBT tend to focus more attention on its technology, methodology, and curricular components, the ultimate utility of SBT as an educational format relies on the effectiveness of the debriefing rendered during a session.[2] Some authors consider it the most crucial element of SBT.[3] It is within the debriefing that SBT participants identify their learning gaps and develop strategies for improving them, usually under the guidance of the educator/facilitator leading the SBT session. Such guidance can be particularly challenging in the setting of an inter-professional team in which, by definition, learners come from different backgrounds and perspectives.

Debriefing has played an integral role in the medical simulation since its implementation, and its advantages are well-founded in educational theory. Debriefing strategies are based upon learner types, scenario objectives, and preference of the educator leading the debrief. Irrespective of technique, debriefing leads to meaningful learning opportunities via experiential reflection. Reflective practice outlines how it is not the experience alone but the deliberate reflection on experience that leads to active learning. When appropriately applied to clinical practice and educationally productive debriefing following medical simulation can inevitably improve patient safety.[4]

Medical debriefing is based upon the military and aviation fields, which have team building, crisis management, and high-risk situations in common. Anesthesiology debriefing specifically has its origins within aviation crew resource management (CRM). Military debriefing was developed by Colonel S.L.A Marshall, the chief United States Army historian in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam.[2] He conducted debriefings of the entire military unit immediately following an event. Jeffrey Mitchell, a psychologist, developed the Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD) for civilians, also commonly viewed as the framework for medical debriefing today.[5] CISD is contingent upon its seven phases, including introduction, information discovery, detection of individuals’ thought processes, reaction, symptom description, teaching, and reentry. After repeated plane accidents in the 1960s and 1970s, pilot interviews revealed a lack of adequate training in leadership, decision making, judgment, communication, and crew coordination.[6] When CRM training resulted in improved outcomes for the aviation industry, Gaba et al. developed anesthesia CRM to improve safety in the operating room.[7]

Debriefing can occur either after or during a simulation exercise. It can also be either facilitator-guided or self-guided by simulation learners. Two of the most important aspects of healthcare simulation include debriefing and feedback.[8] The difference between feedback and debriefing is worth clarifying. Feedback is a one-way delivery of performance information to simulation participants with the intent to modify behavior and improve future activity performance.[9] Debriefing, on the other hand, is a bidirectional, interactive, and reflective conversation between facilitator and participant.[10] Of note, the act of debriefing itself is more important than the specific technique utilized. There has been no data to suggest that there is a best or optimal way to debrief, but rather a large variety of techniques available from which simulation educators and experts can choose.

Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Function

Structurally, a debriefing has seven elements. The facilitator guides and fosters learning. The participants, in an inter-professional setting, learn with, from, and about each other. The experience element in SBT includes the scenario and the after-action review. The impact of the experience focuses on participants’ experiences, comparing their experiences to a standard. The recollection element has the participants recalling and self-assessing their actions. Mechanisms for reporting events include video playback, verbal discussion, or simulator feedback. Finally, the last element, timing, relates to the length of the debrief and the interval between it and the actual SBT. Although several theoretical frameworks exist related to the interaction between SBT and debriefing, Kolb’s experiential learning model is a useful schema.[11] For an inter-professional team involved in an SBT activity, it begins with the participants’ concrete experimentation in the form or the simulated scenario. The debriefing then leads the participants through the process of reflective observation and abstract conceptualization, promoting active experimentation and behavior change.

Debriefing refers to facilitator-guided reflection in experiential learning to help identify and bridge gaps in participants’ knowledge and skill acquisition. Successful debriefing involves the active participation of learners as opposed to passive receipt of feedback. Performance reviews should be predicated on learning and improvement compared to a specific standard and open discussion of events during the simulation.[12] Facilitator-guided post-event debriefing is most commonly utilized to ensure the achievement of learning objectives and that conversation is organized and inclusive of all participants.[13] One theory suggests it is helpful for facilitators to position themselves not as experts but as co-learners to facilitate educational goals, as indicated by Fanning and Gaba.[14] Alternatively, the facilitator can function as a subject matter expert and provide useful guidance based on their training, experience, and expertise.[15]

Scripted or structured debriefing during clinical care and simulation-based education may aid facilitators. The EXPRESS (Examining Pediatric Resuscitation Education using Simulation and Scripting) trial aimed to standardize Pediatric Advanced Life support (PALS) course debriefings for novice instructors. Learning and performance outcomes were measured based on a scripted debriefing tool.[16] Novice instructors that utilized the debriefing script were more effective at expanding learners’ knowledge acquisition and procedural skills than those who did not use a script. Following the EXPRESS study, the authors collaborated with the American Heart Association (AHA) to develop a novel debriefing tool for both the PALS and the Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) course.[17] The AHA debriefing tool utilized the “gather, analyze and summarize (GAS)” debriefing model to codify PALS and ACLS scenarios. This tool was ultimately incorporated into the 2011 PALS and ACLS instructor materials to facilitate learning.

The advocacy inquiry technique is commonly utilized by educators to unearth a shared mental model during simulation scenarios. Educators aim to elucidate a learner’s rationale for action by stating a concrete observation before inquiring about the participant’s perspective. A robust and interactive discussion results when facilitators elicit alternatives to clinical decisions, risks, and benefits of interventions, varying management options, or other pertinent performance implications.[18] Focused facilitation methods allow learners to explore mental models to enable comprehensive discussions and potentially improve patient safety.

Issues of Concern

Organizational-, participant-, and debriefer-specific barriers can adversely influence inter-professional team SBT debriefings. At the organizational level, both a lack of institutional support for SBT and the absence of an appropriate learning structure for it can undermine SBT activities. Manifestations may include off-limit topics of discussion or the absence of a safe learning environment. Identifying and recruiting a champion within the leadership group can address these difficult issues. Participant-specific barriers can arise due to learner-specific characteristics or situation-specific issues that lead to difficulties with participants during the debriefing process. Learner-specific examples include the shy participant, the indifferent participant, the dominating participant with poor insight, and the dominating participant showing off. Situation-specific examples include participants who react emotionally or defensively because of the scenario.[19] Strategies to address participant-specific barriers include both non-verbal and verbal communicative techniques. Important non-verbal methods involve remaining silent to invite participant input, establishing eye contact, and using body language to project an inviting attitude. Communicative strategies include a variety of techniques such as normalization, validation, generalization, paraphrasing, broadening, previewing, and naming the dynamic.[19]

Debriefer-specific barriers to effective debriefing in inter-professional team SBT can arise due to a lack of knowledge of the facilitator related to debriefing technique, human factors, or teamwork dynamics. Additionally, they can result from the inherent cognitive biases, heuristics, and errors of attribution of the facilitators themselves. Furthermore, the debriefer may fail to create a learning environment with the necessary psychological safety needed to allow participants to contribute. Finally, the facilitator may end up focusing on “who is right” instead of “what is right.”[20]

Employing the Debriefing Duties can help a facilitator in avoiding debriefer-specific barriers. These duties are threefold: Make it Safe, Make it Stick, Make it Last. In making it safe, the facilitator engages the learner, creates an inviting learning environment, and establishes psychological safety. In making it stick, the debriefer guides the participants to identify their performance gaps and develop solutions to them. Finally, in making it last, the facilitator challenges each participant to identify at least one take-home learning point on which to work in the clinical environment.

Despite the widespread acceptance of simulation as an integral teaching modality, many educators have little or no formal training in debriefing and may struggle to facilitate effectively. There are several practical guides to model a successful debriefing process. Self-guided debriefing refers to the use of cognitive aids as a basis for reflection and formative self-assessment.[21] As opposed to post-event debriefing, within-event debriefing, also known as “in-simulation debriefing,” “concurrent debriefing,” “stop-action debriefing,” or “micro-debriefing,” involves the transient interruption of the simulation activity.[22] “Rapid cycle deliberate process” refers to within event debriefing to refine procedural and resuscitation skills. This method allows the facilitator to stop the actions of learners at any given time and utilize the “pause, rewind 10 seconds, and try it again” approach to enable participants to re-attempt an action following corrective feedback. With this approach, participants can maximize their performance in real-time.[23]

Curriculum Development

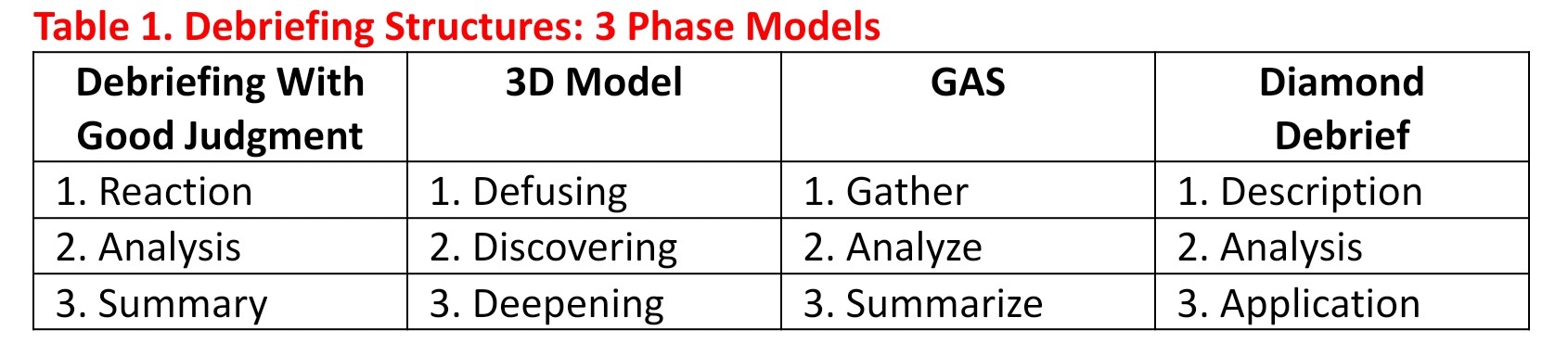

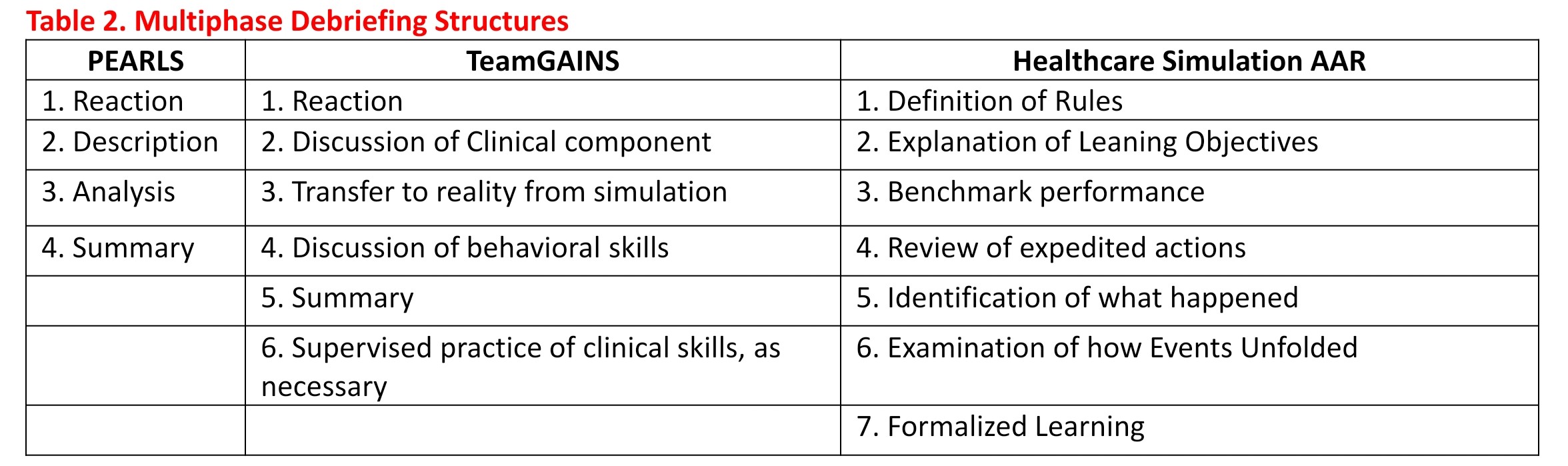

The two main types of facilitator-guided post-event debriefing models include a 3-phase structure and a multi-phase structure. Each debriefing method consists of an analysis of events and a summary or application phase, in which learning is reinforced and teaching objectives are reviewed. The glaring difference between these two conversational structures is when dealing with learners’ emotional responses or reactions. Reaction time allows participants to engage in exploration in a less emotionally charged environment.[24]

The obstacles that may hinder a successful debriefing session include the prohibitively high cost of simulation educator training, limited educator exposure in debriefing experience or education, and the lack of experienced simulation facilitators to provide mentoring to junior faculty. Inadequate or incomplete debriefing can take away from medical knowledge and procedural skill acquisition, and learner attitudes. Novice simulation educators are challenged in creating a structured debriefing session that encourages meaningful discussions, promotes critical reflection, codifies simulation events, and provides open and honest performance feedback to learners.

Clinical Clerkships

There are various ways to structure an effective debriefing session that allows learners to uncover their frame of reference and reorganize their educational agenda. The Center for Medical Simulation in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has lead simulation educator courses called “Debriefing with Good Judgement.”[25] The approach is characterized by four basic principles, including (1) outlining learning objectives before the simulation session, (2) setting clear cut expectations for the simulation session, (3) approaching participants with feedback and curiosity, and (4) organizing the debriefing session into the reaction, analysis and summary phases utilizing the advocacy inquiry technique.

Three-Phase Debriefing Structures

Rudolph et al. first described the 3-phase conversational structure for debriefing, including the reaction, analysis, and summary phases.[24] The reaction phase requires learners to explore the emotional impact of their responses to the simulation experience. A common leading question from the facilitator would be, “How did you feel during the activity?” The analysis phase is more concrete, with a focus on how and why events unfolded the way they did during the simulation. The third, or summary phase, seeks to extract pertinent learning objectives and codify the insights that were highlighted during the analysis phase.[26] Zigmont et al. described a similar model. and is known as the “3D model,” referring to defusing, discovering, and deepening.[27] Each phase is similar in content to that described by Rudolph.

The GAS model was developed in 2009 by the Winter Institute for Simulation, Education, and Research in Pittsburgh in conjunction with the AHA.[28] The first, or gather phase, encourages the team to establish a shared mental model during the summary of simulation events. The analysis phase focuses on learner-centered reflection during the unfolding of the simulation scenario. Learners are asked pointed questions to promote rumination and reflection on thought processes. The final or summary phase ensures that learning objectives have been reviewed and teaching points are solidified. The AHA has adopted this method for the PALS course. Yet another 3 phase debriefing method, the “diamond debriefing” method, omits a reaction or defusing phase.[29] This structure utilizes a description, analysis, and application phase. The application phase inquires how learners will apply lessons learned during the simulation debriefing to their clinical practice.

Multi-Phase Debriefing Structures

A blended approach to debriefing known as ‘‘PEARLS’’ (Promoting Excellence and Reflective Learning in Simulation) utilizes a 4-phase debriefing framework.[30] This expands on Rudolph’s three-phase model by adding a description phase to allow for the summarization of key events or clinical challenges faced during the simulation. There are six sequential phases in the Team-Guided team self-correction, Advocacy-Inquiry, and Systemic-constructivist (TeamGAINS) model.[26] This model has been associated with positive ratings of the learner’s psychological safety, debriefing utility, and leader inclusivity. Instead of focusing on individual behavior, this model focuses on team dynamics and the intricacies of group interactions and relationships.[31]

Another 7-phase model known as healthcare simulation after-action review (AAR) is based upon the US Army’s AAR construct.[15] The phases can be remembered using the acronym DEBRIEF. This methodology is unique in that it emphasizes the review of teaching objectives, relies on performance benchmarks, and urges the simulation facilitator to reveal the expected outcome of the scenario. As a shared mental model is created, the learners’ performance is objectively compared to a known standard or performance benchmark.

Table 1. Debriefing Structures: 3 Phase Models

Table 2. Multiphase Debriefing Structures

Procedural Skills Assessment

According to Sawyer et al., seven elements are considered essential to a successful debrief, including psychological safety, establishing clear cut boundaries or debriefing rules, commencing the simulation session with a “basic assumption,” creating a shared mental model, addressing teaching objectives, using open-ended questions, and utilizing silence appropriately.[32] Psychological safety is essential to optimize learning during the simulation. Psychological safety is defined as the ability to ‘‘behave or perform without fear of negative consequences to self-image, social standing, or career trajectory.”[33] For this requirement, learners must express their opinions without fear of personal harm or rejection. If the team is not performing up to expected standards, the facilitator should dissect the frame of reference that leads to the actions observed. Learners should be active participants in a confidential debrief discussion, and the focus is on performance improvement as opposed to individual criticism. A shared mental model allows both the facilitator and learners to have a mutual understanding of events. Typically, this is accomplished by having team members review the events of each scenario with facilitator-guided input.

Clear learning objectives should be highlighted and incorporated into every simulation scenario and debriefing. On behalf of the facilitator, open-ended questions can expedite discussion and foster reflection and self-assessment both individually and within the team dynamic.[34] Silence can genuinely be golden when utilized during a debriefing session. A period of silence follows the facilitator asking an open-ended question so that learners can formulate their thoughts, critically analyze their mental processes, and construct a definitive response to the facilitator’s inquiry. Facilitators must exhibit patience after posing questions and use silence effectively as a tool.[35] Eppich and Cheng emphasize learner self-assessment, directive performance feedback, and focused facilitation as the tenets of successful debriefing.[30]

Medical Decision Making and Leadership Development

First described in business and organizational behavior literature, the advocacy inquiry technique allows the facilitator to explain their observation of intervention and then enquire about the learners’ frame of mind concerning this action. The guided team self-correction method enables simulation participants to correct their own actions.[36] Learners compare themselves to a predefined benchmark of teamwork skills and can analyze what they executed well and poorly. The facilitator serves to guide the conversation through leading questions and allows the team to analyze and self-correct their actions, before sharing his/her insights.

Circular questions allow an outsider’s perspective on the dyadic relationship between two learners. These questions ask participants to “circle back” and comment on an interaction in which they took part. In the debriefing process, circular questions are useful because they allow tracking of behavioral patterns, incite the generation of new information, and encourage perspective.[26] Co-debriefing is when more than one facilitator is involved in the debriefing process. Cheng et al. describe how co-debriefing improves effective cross-monitoring and the ability to manage learners’ needs and expectations.[37] Video review during debriefing is a useful tool for learners to analyze their reactions and interventions at their leisure. Although widely recommended and generally exciting for learners, numerous studies have shown no educational benefits from video enhanced debriefing.[38] Video-assisted debriefing, when utilized, should focus on critical clips that highlight learning objectives or areas of exemplary or suboptimal performance.

Continuing Education

As stated previously, the debriefing process must create a psychologically safe environment that allows active engagement from learners despite potential threats to their professional and social identity. Rudolph et al. describe four activities that foster such an environment.[39] Firstly, the facilitator should introduce him or herself along with credentials and previous experience while all learners do the same. Faculty can also share a personal goal, which models an environment of frank and candid communication. At the beginning of each simulation session, learning objectives, simulator properties, and formative or summative assessment of performance should be clearly defined for learners. Effective simulation is dependent upon the learners’ suspension of disbelief. The instructor should acknowledge the simulation environment and mannequin’s limitations while seeking a commitment from learners to perform as though they were in a real clinical situation. Simulation educators should also convey curiosity and concern for the learner’s perspective, which can help foster a psychologically safe learning environment.[39] As learners progress from formative to summative evaluations and competency-based education has become mandatory, debriefing is an effective tool in assisting learners through competency levels.[40] Debriefing also serves as a valuable device to evaluate the Core Entrustable Professional Activities and ACGME resident milestones.[41]

There are several well-established methods for assessing the debriefer, including the Objective Structured Assessment of Debriefing (OSAD) and the Debriefing Assessment for Simulation in Healthcare (DASH). Personal and institutional preferences are largely responsible for the chosen method. Developed by the Imperial College London, OSAD consists of a 1-page rubric for simulation and clinical debriefings for both novice and advanced educators.[42] Eight components, including the approach of the debriefer, the establishment of a learning environment, learner engagement, reaction, reflection, analysis of performance, performance gaps, and future application to clinical practice, are rated based on poor, average, or good practice, leading to a score from 1 to 5 points. Harvard’s Center for Medical Simulation developed DASH.[43] This debriefing inventory rates various elements, including establishment and maintenance of an engaging learning environment, debriefing organization and structure, and identification and exploration of performance gaps rated on a scale from 1 to 7.

Clinical Significance

Debriefing is among the most important aspects of simulation-based learning. David Kolb has described the importance of reflection and analysis of the development of experiential learning theory.[44] Ericsson has emphasized that repetition and feedback are essential ingredients for learner performance improvement.[45] Phrampus and O’Donnell have designed a structured, debriefing approach during the simulation.[46] The eight aspects of this tool include:

- Reducing the time between performance and debriefing as much as possible

- Identifying and addressing performance and perception gaps

- Creating a safe environment to enhance learner comfort and participation

- Learner engagement in self-reflection

- Instructors should espouse strong facilitation and debriefing skills

- Debriefing should not be comprehensive and should focus on only a few learning objectives or educational goals that are manageable

- Structured debriefing should preclude broad, open-ended questions, such as “what happened” and utilize questions such as “what was your thought process when you first encountered the patient?”

- Faculty should engage in active listening and pay particular attention to nonverbal cues from learners

The “conscious competence” learning model can aid in guiding the debriefing process.[47] Learners with a perception gap are at the start of the “unconscious incompetence” stage of learning. The ability to recognize their performance deficiency serves as the impetus for a perception gap. The second stage in this model is “conscious incompetence,” whereby learners are conscious of the discrepancy in their thinking process or skills. A simulation session can have the simple goal of enlightening the learner to the presence of a perception gap and closing the gap with the aid of the facilitator. The conscious incompetence phase is the perfect time to introduce cognitive aids, short didactics with management strategies, or useful algorithms to enhance medical knowledge and skills training. This aids the learner in transitioning to the “conscious competence” phase. At this phase, the learner has sufficient prerequisite knowledge and ability but must focus on performing well.[48]

When they are working effectively, inter-professional healthcare teams' productivity is more than the sum of its individual members whose autonomous actions can have profound impacts on team function. Such behavior is characteristic of a complex adaptive system.[49] SBT, therefore, takes on even more importance, since training the entire interprofessional team as a unit results in benefits beyond those gained by each team member. Such training positively impacts team behaviors, care processes, and patient outcomes.[50] These improvements occur as a result of effective debriefing during the SBT. In fact, debriefing can improve team performance by up to 25% after experiential learning activities such as SBT.[51] Viewed from this perspective, the clinical significance of effective debriefing in inter-professional team SBT is clear.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

To optimize team outcomes related to debriefing inter-professional teams in SBT, the learning objectives, curriculum, and scenarios should focus on team-based competencies in lieu of task-based ones. In this manner, the participants will avoid the burden of learning both technical and non-technical skills. Other essential strategies include involving the entire team in the debriefing and meeting their multiple needs, focusing on team-based concepts rather than individual-based topics, and employing reliable, valid assessment tools to measure the teamwork during the SBT to allow for objective use to guide the debriefing. By focusing on team communication, cooperation, and coordination during the debriefing of inter-professional team SBT, the likelihood of their transfer to the actual clinical environment with concomitant improvement of patient care increases.[52]

The most commonly used and studied method for simulation debriefing, facilitator-guided post-event debriefing, has been shown to improve individual and team performance in many contexts.[53] With effective debriefing, learners can improve upon technical skills, achieve mastery learning, and improve adherence to resuscitation guidelines.[22] There is some evidence to suggest that post-event debriefing is preferred to within-event debriefing by learners due to improved skill retention.[54] A debriefing session's success depends on the expertise of the facilitator and the group of learners relative to the simulation scenario and teaching objectives.[55] Novice learners require more directive feedback from facilitators than those with more experience. Facilitators can create a memorable debriefing experience by enumerating educational objectives before the simulation activity, matching simulation content to learner experience level, and using appropriate techniques such as GAS or the advocacy inquiry method.

There is a form of debriefing with several clinical experiences, including intraoperative arrest or patient death. These can range from discussing a medical error to a complex interdisciplinary trauma response in a formal or informal setting. Structured debriefings are most commonly found in the resuscitation literature.[56] Debriefing allows the formative evaluation of a resident or medical students’ clinical performance. In daily practice, the skills for simulation debriefing can be extrapolated to provide feedback to learners in the operating room or intensive care unit setting. Veloski et al. found that prolonged and persistent feedback from faculty had a profound impact on learners’ clinical performance.[57] In an environment where all medical personnel has the responsibility to teach throughout their careers, debriefing skills developed during simulation can have an essential impact in the clinical arena. Aiding healthcare practitioners in developing the habitual practice of eliciting and delivering feedback effectively can help in contributions to patient safety.

Because there is no formalized or structured curriculum for the development of debriefing techniques, simulation educators should rely on the principles of learning theory to guide their approach. Rudolph et al. stress the need to alter pre-existing cognitive frames to construct new understanding and practice regimens for learners.[57] Participants should be encouraged to increase their cognitive capacity for learning, and facilitators should provide ample opportunities for the practice of clinical skills while providing constructive feedback. The medical knowledge and clinical skills gained during simulation would seamlessly transfer to clinical practice and patient care. This is more likely if facilitators integrate learning into larger frameworks and if participants have a foundational understanding of the underlying principles being taught. Most importantly, the nuances of successful debriefing require the development of trust between the facilitator and learner, as the emotional and cognitive dimensions of learning are intimately intertwined. In this way, a successful learning environment is attuned to the learners’ emotional state and motivations.[58]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Beaubien JM, Baker DP. The use of simulation for training teamwork skills in health care: how low can you go? Quality & safety in health care. 2004 Oct:13 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i51-6 [PubMed PMID: 15465956]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceIssenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Medical teacher. 2005 Jan:27(1):10-28 [PubMed PMID: 16147767]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLopreiato JO, Sawyer T. Simulation-based medical education in pediatrics. Academic pediatrics. 2015 Mar-Apr:15(2):134-42. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.10.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25748973]

Cook DA, Hatala R, Brydges R, Zendejas B, Szostek JH, Wang AT, Erwin PJ, Hamstra SJ. Technology-enhanced simulation for health professions education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011 Sep 7:306(9):978-88. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1234. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21900138]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMartinchek M, Bird A, Pincavage AT. Building Team Resilience and Debriefing After Difficult Clinical Events: A Resilience Curriculum for Team Leaders. MedEdPORTAL : the journal of teaching and learning resources. 2017 Jul 12:13():10601. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10601. Epub 2017 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 30800803]

Harris D, Li WC. Cockpit design and cross-cultural issues underlying failures in crew resource management. Aviation, space, and environmental medicine. 2008 May:79(5):537-8 [PubMed PMID: 18500053]

Gaba DM, Howard SK, Flanagan B, Smith BE, Fish KJ, Botney R. Assessment of clinical performance during simulated crises using both technical and behavioral ratings. Anesthesiology. 1998 Jul:89(1):8-18 [PubMed PMID: 9667288]

Howard SK, Gaba DM, Fish KJ, Yang G, Sarnquist FH. Anesthesia crisis resource management training: teaching anesthesiologists to handle critical incidents. Aviation, space, and environmental medicine. 1992 Sep:63(9):763-70 [PubMed PMID: 1524531]

Voyer S, Hatala R. Debriefing and feedback: two sides of the same coin? Simulation in healthcare : journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare. 2015 Apr:10(2):67-8. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000075. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25710319]

Arafeh JM, Hansen SS, Nichols A. Debriefing in simulated-based learning: facilitating a reflective discussion. The Journal of perinatal & neonatal nursing. 2010 Oct-Dec:24(4):302-9; quiz 310-1. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0b013e3181f6b5ec. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21045608]

ALQahtani DA, Al-Gahtani SM. Assessing learning styles of Saudi dental students using Kolb's Learning Style Inventory. Journal of dental education. 2014 Jun:78(6):927-33 [PubMed PMID: 24882779]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceArcher JC. State of the science in health professional education: effective feedback. Medical education. 2010 Jan:44(1):101-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03546.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20078761]

Peng CR, Schertzer K. Rapid Cycle Deliberate Practice in Medical Simulation. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31855377]

Fanning RM, Gaba DM. The role of debriefing in simulation-based learning. Simulation in healthcare : journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare. 2007 Summer:2(2):115-25. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3180315539. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19088616]

Sawyer TL, Deering S. Adaptation of the US Army's After-Action Review for simulation debriefing in healthcare. Simulation in healthcare : journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare. 2013 Dec:8(6):388-97. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e31829ac85c. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24096913]

Hughes PG, Hughes KE. Briefing Prior to Simulation Activity. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31424818]

Rudolph JW, Simon R, Rivard P, Dufresne RL, Raemer DB. Debriefing with good judgment: combining rigorous feedback with genuine inquiry. Anesthesiology clinics. 2007 Jun:25(2):361-76 [PubMed PMID: 17574196]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAhmed M, Arora S, Russ S, Darzi A, Vincent C, Sevdalis N. Operation debrief: a SHARP improvement in performance feedback in the operating room. Annals of surgery. 2013 Dec:258(6):958-63. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828c88fc. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23478533]

Grant VJ, Robinson T, Catena H, Eppich W, Cheng A. Difficult debriefing situations: A toolbox for simulation educators. Medical teacher. 2018 Jul:40(7):703-712. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1468558. Epub 2018 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 29792100]

Fernandez R, Vozenilek JA, Hegarty CB, Motola I, Reznek M, Phrampus PE, Kozlowski SW. Developing expert medical teams: toward an evidence-based approach. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2008 Nov:15(11):1025-36. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00232.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18785937]

Dubé MM, Reid J, Kaba A, Cheng A, Eppich W, Grant V, Stone K. PEARLS for Systems Integration: A Modified PEARLS Framework for Debriefing Systems-Focused Simulations. Simulation in healthcare : journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare. 2019 Oct:14(5):333-342. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000381. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31135684]

Hunt EA, Duval-Arnould JM, Nelson-McMillan KL, Bradshaw JH, Diener-West M, Perretta JS, Shilkofski NA. Pediatric resident resuscitation skills improve after "rapid cycle deliberate practice" training. Resuscitation. 2014 Jul:85(7):945-51. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.02.025. Epub 2014 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 24607871]

Gross IT, Abrahan DG, Kumar A, Noether J, Shilkofski NA, Pell P, Bahar-Posey L. Rapid Cycle Deliberate Practice (RCDP) as a Method to Improve Airway Management Skills - A Randomized Controlled Simulation Study. Cureus. 2019 Sep 1:11(9):e5546. doi: 10.7759/cureus.5546. Epub 2019 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 31523589]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRudolph JW, Simon R, Dufresne RL, Raemer DB. There's no such thing as "nonjudgmental" debriefing: a theory and method for debriefing with good judgment. Simulation in healthcare : journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare. 2006 Spring:1(1):49-55 [PubMed PMID: 19088574]

Maestre JM, Rudolph JW. Theories and styles of debriefing: the good judgment method as a tool for formative assessment in healthcare. Revista espanola de cardiologia (English ed.). 2015 Apr:68(4):282-5. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2014.05.018. Epub 2014 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 25239179]

Kolbe M, Weiss M, Grote G, Knauth A, Dambach M, Spahn DR, Grande B. TeamGAINS: a tool for structured debriefings for simulation-based team trainings. BMJ quality & safety. 2013 Jul:22(7):541-53. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000917. Epub 2013 Mar 22 [PubMed PMID: 23525093]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZigmont JJ, Kappus LJ, Sudikoff SN. The 3D model of debriefing: defusing, discovering, and deepening. Seminars in perinatology. 2011 Apr:35(2):52-8. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2011.01.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21440811]

Cheng A, Rodgers DL, van der Jagt É, Eppich W, O'Donnell J. Evolution of the Pediatric Advanced Life Support course: enhanced learning with a new debriefing tool and Web-based module for Pediatric Advanced Life Support instructors. Pediatric critical care medicine : a journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies. 2012 Sep:13(5):589-95 [PubMed PMID: 22596070]

Jaye P, Thomas L, Reedy G. 'The Diamond': a structure for simulation debrief. The clinical teacher. 2015 Jun:12(3):171-5. doi: 10.1111/tct.12300. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26009951]

Eppich W, Cheng A. Promoting Excellence and Reflective Learning in Simulation (PEARLS): development and rationale for a blended approach to health care simulation debriefing. Simulation in healthcare : journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare. 2015 Apr:10(2):106-15. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000072. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25710312]

Kinnear J, Smith B, Akram M, Wilson N, Simpson E. Using expert consensus to develop a simulation course for faculty members. The clinical teacher. 2015 Feb:12(1):27-31. doi: 10.1111/tct.12233. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25603704]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSawyer T, Eppich W, Brett-Fleegler M, Grant V, Cheng A. More Than One Way to Debrief: A Critical Review of Healthcare Simulation Debriefing Methods. Simulation in healthcare : journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare. 2016 Jun:11(3):209-17. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000148. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27254527]

Tella S, Smith NJ, Partanen P, Turunen H. Learning Patient Safety in Academic Settings: A Comparative Study of Finnish and British Nursing Students' Perceptions. Worldviews on evidence-based nursing. 2015 Jun:12(3):154-64. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12088. Epub 2015 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 25872460]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBoet S, Bould MD, Bruppacher HR, Desjardins F, Chandra DB, Naik VN. Looking in the mirror: self-debriefing versus instructor debriefing for simulated crises. Critical care medicine. 2011 Jun:39(6):1377-81. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820eb8be. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21317645]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHicks CW, Rosen M, Hobson DB, Ko C, Wick EC. Improving safety and quality of care with enhanced teamwork through operating room briefings. JAMA surgery. 2014 Aug:149(8):863-8. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.172. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25006700]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFlentje M, Eismann H, Sieg L, Friedrich L, Breuer G. [Simulation as a Training Method for the Professionalization of Teams]. Anasthesiologie, Intensivmedizin, Notfallmedizin, Schmerztherapie : AINS. 2018 Jan:53(1):20-33. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-105261. Epub 2018 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 29320789]

Cheng A, Palaganas J, Eppich W, Rudolph J, Robinson T, Grant V. Co-debriefing for simulation-based education: a primer for facilitators. Simulation in healthcare : journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare. 2015 Apr:10(2):69-75. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000077. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25710318]

Savoldelli GL, Naik VN, Park J, Joo HS, Chow R, Hamstra SJ. Value of debriefing during simulated crisis management: oral versus video-assisted oral feedback. Anesthesiology. 2006 Aug:105(2):279-85 [PubMed PMID: 16871061]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRudolph JW, Raemer DB, Simon R. Establishing a safe container for learning in simulation: the role of the presimulation briefing. Simulation in healthcare : journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare. 2014 Dec:9(6):339-49. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000047. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25188485]

Boulet JR. Summative assessment in medicine: the promise of simulation for high-stakes evaluation. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2008 Nov:15(11):1017-24. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00228.x. Epub 2008 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 18778377]

Martinelli SM, McGraw KA, Kalbaugh CA, Vance S, Viera AJ, Zvara DA, Mayer DC. A Novel Core Competencies-Based Academic Medicine Curriculum: Description and Preliminary Results. The journal of education in perioperative medicine : JEPM. 2014 Jul-Dec:16(10):E076 [PubMed PMID: 27175398]

Arora S, Ahmed M, Paige J, Nestel D, Runnacles J, Hull L, Darzi A, Sevdalis N. Objective structured assessment of debriefing: bringing science to the art of debriefing in surgery. Annals of surgery. 2012 Dec:256(6):982-8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182610c91. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22895396]

Brett-Fleegler M, Rudolph J, Eppich W, Monuteaux M, Fleegler E, Cheng A, Simon R. Debriefing assessment for simulation in healthcare: development and psychometric properties. Simulation in healthcare : journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare. 2012 Oct:7(5):288-94. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3182620228. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22902606]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrackenreg J. Issues in reflection and debriefing: how nurse educators structure experiential activities. Nurse education in practice. 2004 Dec:4(4):264-70. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2004.01.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19038168]

Ericsson KA. Deliberate practice and acquisition of expert performance: a general overview. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2008 Nov:15(11):988-94. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00227.x. Epub 2008 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 18778378]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMusits AN, Phrampus PE, Lutz JW, Bear TM, Maximous SI, Mrkva AJ, OʼDonnell JM. Physician Versus Nonphysician Instruction: Evaluating an Expert Curriculum-Competent Facilitator Model for Simulation-Based Central Venous Catheter Training. Simulation in healthcare : journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare. 2019 Aug:14(4):228-234. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000374. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31116170]

Kinsella EA. Professional knowledge and the epistemology of reflective practice. Nursing philosophy : an international journal for healthcare professionals. 2010 Jan:11(1):3-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-769X.2009.00428.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20017878]

Donlan P. Developing Affective Domain Learning in Health Professions Education. Journal of allied health. 2018 Winter:47(4):289-295 [PubMed PMID: 30508841]

Pype P, Mertens F, Helewaut F, Krystallidou D. Healthcare teams as complex adaptive systems: understanding team behaviour through team members' perception of interpersonal interaction. BMC health services research. 2018 Jul 20:18(1):570. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3392-3. Epub 2018 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 30029638]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDoumouras AG, Hamidi M, Lung K, Tarola CL, Tsao MW, Scott JW, Smink DS, Yule S. Non-technical skills of surgeons and anaesthetists in simulated operating theatre crises. The British journal of surgery. 2017 Jul:104(8):1028-1036. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10526. Epub 2017 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 28376246]

Tannenbaum SI, Cerasoli CP. Do team and individual debriefs enhance performance? A meta-analysis. Human factors. 2013 Feb:55(1):231-45 [PubMed PMID: 23516804]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGarden AL, Le Fevre DM, Waddington HL, Weller JM. Debriefing after simulation-based non-technical skill training in healthcare: a systematic review of effective practice. Anaesthesia and intensive care. 2015 May:43(3):300-8 [PubMed PMID: 25943601]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBoet S, Bould MD, Sharma B, Revees S, Naik VN, Triby E, Grantcharov T. Within-team debriefing versus instructor-led debriefing for simulation-based education: a randomized controlled trial. Annals of surgery. 2013 Jul:258(1):53-8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31829659e4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23728281]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceXeroulis GJ, Park J, Moulton CA, Reznick RK, Leblanc V, Dubrowski A. Teaching suturing and knot-tying skills to medical students: a randomized controlled study comparing computer-based video instruction and (concurrent and summary) expert feedback. Surgery. 2007 Apr:141(4):442-9 [PubMed PMID: 17383520]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCheng A, Grant V, Dieckmann P, Arora S, Robinson T, Eppich W. Faculty Development for Simulation Programs: Five Issues for the Future of Debriefing Training. Simulation in healthcare : journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare. 2015 Aug:10(4):217-22. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000090. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26098492]

Couper K, Perkins GD. Debriefing after resuscitation. Current opinion in critical care. 2013 Jun:19(3):188-94. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32835f58aa. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23426138]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRudolph JW, Simon R, Raemer DB, Eppich WJ. Debriefing as formative assessment: closing performance gaps in medical education. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2008 Nov:15(11):1010-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00248.x. Epub 2008 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 18945231]

Sigmundsson H, Trana L, Polman R, Haga M. What is Trained Develops! Theoretical Perspective on Skill Learning. Sports (Basel, Switzerland). 2017 Jun 15:5(2):. doi: 10.3390/sports5020038. Epub 2017 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 29910400]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence