Introduction

Aneurysmal bone cysts are non-malignant, tumor-like, vascular lesions comprised of blood-filled channels. Although they can occur in any bone, they are most common in the femur, tibia, and vertebrae.[1] Their expansile nature may result in pain and inflammation, and disruption of joints and growth plates. They can grow aggressively, be locally destructive, and weaken bones to the point of pathologic fracture.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of aneurysmal bone cysts is currently unknown, although they appear to be due to vascular malformations in the bone.

There are three main theories for their etiology:[2]

- Aneurysmal bone cysts occur as a result of a separate primary bone tumor; this may be due to the relatively high rate (1 in 3) of an accompanying bone lesion. These lesions are frequently chondromyxoid, fibromas, chondrosarcomas, fibrous dysplasia, giant cell tumors of the bone, osteoblastomas, osteosarcomas, among others.

- They form as the primary tumor.

- They form at a site of previous trauma.

A portion of aneurysmal bone cysts now appears to be neoplastic. Genetic studies of the tumor have revealed that up to 69% of primary aneurysmal bone cysts contain a clonal t(16,17) translocation. The t(16,17) fusion causes an upregulation of the TRE17/USP6 oncogene, which activates NF-kB and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). The MMPs break down the extracellular matrix, allowing for the swift growth of the lesions.[3] Secondary aneurysmal bone cysts have not been found to contain this translocation.

Epidemiology

Aneurysmal bone cysts are a rare osseous tumor, comprising 1% to 6% of primary osseous tumors. According to a retrospective study, the incidence of primary aneurysmal bone cysts was 0.14 per 10 people. The majority of patients diagnosed with an aneurysmal bone cyst (8 out of 10) are children and adolescents less than 20 years old. There is a slightly increased incidence rate seen in females (1 to 1.3).[4] Because aneurysmal bone cysts primarily manifest in pediatric patients, growth plate involvement and permanent limb length deformities are of great concern.

By far, the majority of aneurysmal bone cysts present in the metaphysis of long bones (67%). They also occur in the spine (15%), particularly the posterior elements, pelvis (9%), and less frequently, they can appear in the craniofacial bones and epiphyses.[5]

Pathophysiology

Researchers believe aneurysmal bone cysts to be due to a vascular malformation, with the definitive cause being unknown. The current thinking is that the vascular malformations lead to increased pressure and expansion in the bone itself, causing erosion and resorption of the involved bone.[2] The majority of primary aneurysmal bone cysts lesions possess a t(16,17) gain-of-function translocation that upregulates the TRE17/USP6 oncogene, which halts osteoblastic maturation.[6]

Histopathology

Grossly, aneurysmal bone cysts are composed of blood and hemosiderin-filled cystic cavities, enclosed in a subperiosteal shell of reactive bone. The cavities contain septa of trabeculated bone or osteoid tissue, without endothelium. The stroma is comprised of fibroblasts, spindle cells, osteoid, and multinucleated giant cells.[3] These cells are typically seen at the periphery of the cystic cavities, giving an appearance described as “pigs at the trough.” Mitotic figures commonly present in the lesions, but atypical figures should be absent.

History and Physical

Patients will typically present with an insidious onset of pain over several weeks to months, with possible swelling or palpable mass. A minority of patients present with a sudden onset of pain as the result of a pathological fracture. Occasionally neurological symptoms may be present if the aneurysmal bone cyst is impinging a nerve or if there is spinal involvement.[3]

Evaluation

The evaluation of aneurysmal bone cysts primarily consists of imaging studies, which can typically provide critical clues to the diagnosis.

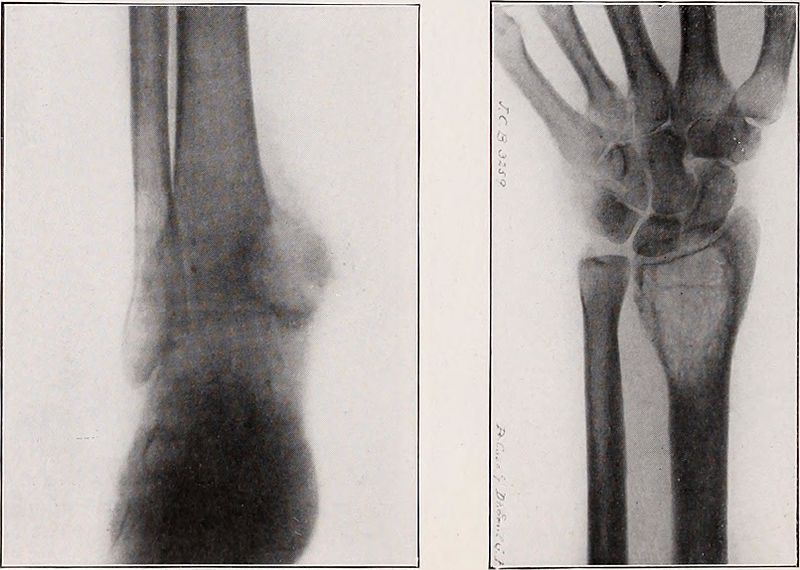

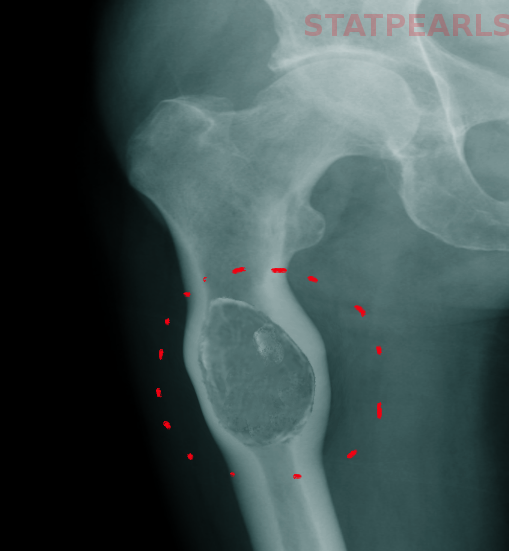

Radiographs illustrate cystic or osteolytic lesions with thin “eggshell” sclerotic borders. The enclosed cavity contains many dividing septa.[2] The surrounding bone may be pushed outwards from its normal anatomy, demonstrating the aggressive, expansile nature of the lesion.

Computed tomography reveals similar characteristics as plain radiographs, although it may define the cystic septa to a greater degree, highlighting the “eggshell” rim. Fluid-fluid levels may be present within the cavities due to the separation of the cellular debris from the serum.

Magnetic resonance imaging again demonstrates similar findings as CT. T1 contrast-enhanced and T2 weighted images can emphasize the septa within the lesion, revealing rims of low T1 and T2 signal [2]. Variably aged blood contained within the cystic cavities are visible on MR as focal areas of hyperintense signal on both T1 and T2 weighted sequences, and double density fluid levels may also be visible. A pathologic fracture may be evident, as demonstrated by osseous and soft tissue edema.

Laboratory studies hold a minimal benefit in the workup and diagnosis of aneurysmal bone cysts, although bears mentioning that alkaline phosphatase levels may present as increased due to the elevated activity of osteoblasts.

Treatment / Management

Once diagnosed with an aneurysmal bone cyst, the patient should obtain a referral to an orthopedic oncologist. Surgical intervention is typically the treatment of choice to prevent pathological fracture. Based on the lesion size and the region of bone involved, either intralesional curettage, intralesional excision, or en bloc (complete) excision may be an option.

Intralesional curettage involves evacuating the cavity of its contents and filling the remaining space with bone graft or cement to strengthen the bone.

Intralesional excision is the preferred treatment of choice, which is similar to curettage: the surgeon makes a broad opening through the osseous wall of the lesion and removes the contents. This process allows a greater amount of the bone to remain intact to reduce patient morbidity when compared to en bloc excision. After the removal of the cystic contents, the surgeon can fill the lesion via bone grafting or other material to supply strength and promote healing of the bone. Differing from curettage, this type of treatment allows the use of various forms of adjuvant therapy to reduce the rates of recurrence, due to the broad opening made to gain access to the cavity. Adjuvant therapies include high-speed burr, argon beam coagulation, phenol, and cryotherapy. This type of excision is also beneficial in aneurysmal bone cysts that occur near joints and other structures where the desire to maintain normal anatomy is crucial for functionality.

En bloc excision consists of removing the entire cavitary lesion from the bone that contains it. When considering en bloc excision, the surgeon must weigh the risks and benefits of the procedure, considering the possible loss of functionality of the area, especially when operating near a joint. Due to the result of significant patient morbidity, en bloc resection is typically reserved for patients with recurrent lesions that were not adequately controlled by less invasive means.[3]

Selective arterial embolization (SAE) may be considered before surgery as an adjuvant, or as a primary treatment if the clinician suspects a severe loss of function or destabilization as a result of local or wide excision of the lesion. In up to 40% of patients being treated primarily with SAE, a second or third embolization attempt is necessary.[7]

Radiotherapy has also found utility as adjuvant therapy in recurrent aneurysmal bone cysts cases. However, clinicians must consider the significant risks associated with radiation therapy. There is at least one documented instance of radiation-induced sarcoma of a patient receiving treatment with external beam radiation for a vertebral aneurysmal bone cyst.[8]

Medical therapies with monoclonal antibodies for non-surgical candidates is an area currently being explored.

Differential Diagnosis

Chondroblastoma – These are cartilaginous tumors typically found in the epiphyses (95%) and apophyses of long bones. Chondroblastomas are nonmalignant and usually discovered when a child has constant pain and swelling in an extremity that is unrelated to activity. Radiographically, they demonstrate sclerotic, well-circumscribed lesions located in the epiphysis that may be crossing the growth plate. A central region of intermediate to high signal on T2/STIR images are visible on MR, as well as central enhancement post-gadolinium. Peritumoral edema is frequently associated, as evidenced by surrounding hyperintense areas on T2 images.[9] Fluid-fluid levels may be present.

Fibrous dysplasia – Predominantly a process found in children and young adults, fibrous dysplasia is a benign, tumor-like process in which healthy bone becomes replaced with fibrous connective tissue and immature trabecular bone. These lesions are due to an error in osteoblastic differentiation and maturation. Usually found incidentally, patients with fibrous dysplasia are typically asymptomatic and require no intervention. However, morbidity can arise when the lesion is expanding and pressing upon nearby structures. They can be monostotic (involving only one bone) or polyostotic (involving multiple bones). Radiographically, the lytic lesions show cortical thinning with endosteal scalloping and well-circumscribed borders. A ground glass matrix is present, and, occasionally, a “rind sign” is present (a thick layer of sclerotic reactive bone around the lesion).[10] CT and MRI are usually not warranted for further evaluation unless pathologic fracture or stress reaction is suspected. A “shepherd’s crook” boney deformity may present in the setting of multiple microfractures and progressive varus stresses in the femoral neck.[11]

Giant cell tumor (GCT) – GCT is a nonmalignant tumor of the bone that typically presents in adults who have reached skeletal maturity. They are aggressive osteolytic neoplasms that may have distant metastases to the lungs; these metastases are usually benign. Although the majority are nonmalignant, up to 8% of GCTs will undergo malignant transformation.[12] GCT commonly presents as chronic pain and swelling at the site, with limitation of movement of the nearby joint. If weight-bearing bones are involved, a pathologic fracture may occur. Radiographs will show a lesion, typically in the epiphysis, with a non-central lytic focus. Subchondral plate involvement is not uncommon. CT will show profound cortical thinning and reveal the absence of matrix mineralization. GCT is the most commonly involved tumor seen with secondary aneurysmal bone cysts.[13]

Telangiectatic osteosarcoma (TOS) – TOS is similar in presentation and appearance to aneurysmal bone cysts. MRI with gadolinium can help differentiate the two by demonstrating a nodular appearance to the tissue surrounding the cavities in TOS, which corresponds to sarcomatous tissue. TOS will also reveal cortical destruction and a corresponding soft-tissue mass.[3] Necrosis may also be present in TOS. However, the only definitive way to differentiate the two diseases is through biopsy of the lesion, which will reveal malignant tumor cells in TOS.

Unicameral bone cyst (UBCs) – Appearing in the first two decades of life, UBCs are fluid-filled lesions surrounded by a fibrous lining of mesothelial cells. Patients will commonly present with pain due to a pathological fracture located in the metaphysis of a long bone. Radiography will reveal an expansile lesion that extends across the entire diameter of the involved bone.[14] Well-defined margins are present without reactive sclerosis. Unlike aneurysmal bone cysts, the diameter of a UBC will not exceed the diameter of the involved bone. The “fallen fragment’ sign is pathognomonic for UBCs, in which fractured intramedullary fragments are radiographically visible inside the cystic cavity.[15]

Staging

The staging of aneurysmal bone cysts has its basis in Enneking’s staging of benign musculoskeletal neoplasms [16]:

- Stage 1: Latent (inactive) - These tumors are usually found incidentally and are asymptomatic.

- Stage 2: Active - These tumors are discovered due to the symptomatic discomfort of the patient. They are steadily growing and may be palpable.

- Stage 3: Aggressive - These tumors are typically found due to significant patient discomfort and a possible visible abnormality with inflammation. Although these tumors are benign, they act very similarly to low-grade malignancy.

Prognosis

Surgical excision of aneurysmal bone cysts is usually curative; however, historically, a spontaneous recurrence rate of 19% has been seen.[17] Recurrences tend to happen within the first year of excision, but patients should be regularly evaluated for recurrence up to 5 years after surgery. In patients that have not yet reached skeletal maturity, recurrence could affect future bone growth and cause deformities.

Complications

Complications during treatment tend to vary depending on the lesion’s location in the skeleton. As with any surgical procedure, the risk of bleeding and infection is of the utmost concern, not only for a superficial wound infection but osteomyelitis as well. Damage to the physis is possible if the lesion is near the growth plate. Pulmonary embolism is also a concern due to venous thromboembolism or fat embolism, as it is with other orthopedic surgeries.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

The patient’s return to activity is dependent on the location of the lesion, the extent of excision (if excised), and the extent of the reconstruction (bone grafting vs. cement). Physical and/or occupational therapy are essential to help reduce morbidity.

Deterrence and Patient Education

As the cause of aneurysmal bone cysts is unknown, measures to deter them from occurring are unknown. It is crucial to educate young patients, particularly children and adolescents who have yet to reach skeletal maturity, and their parents, to seek medical attention if they are experiencing either acute or chronic bone pain.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The patients with aneurysmal bone cysts benefit significantly from an interprofessional team providing their care. Typically, primary care providers or emergency physicians will be the first to evaluate the patients. Chiropractors may also be the first to encounter an aneurysmal bone cyst on their radiographs and must be knowledgable so that they can refer the patient appropriately. After obtaining the initial plain film X-rays, the patient should receive a referral to an orthopedic surgeon. The radiologist will provide imaging interpretation, and an orthopedic oncologist will provide surgical care. Finally, rehabilitation the patient should receive rehabilitation by a physical or occupational therapist. Each of these disciplines must work together to provide the most optimal outcomes for these patients and to allow the patients to return to their normal activity as quickly as possible. [Level 5]

Focus on the patient’s quality of life should be of the utmost concern. Nursing will assist in all phases of the case management, from surgical prep, assisting in surgery, and providing postoperative care, and acting as a liaison between therapists and the treating physician. This type of interprofessional team approach is necessary to optimize outcomes. [Level 5]

Key areas for future research should focus on ways to decrease the functional restriction of patients who have aneurysmal bone cysts close to major joints, as these lesions tend to cause the greatest morbidity. Additionally, further narrowing the inciting cause of aneurysmal bone cysts can help identify populations at risk.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Schreuder HW, Veth RP, Pruszczynski M, Lemmens JA, Koops HS, Molenaar WM. Aneurysmal bone cysts treated by curettage, cryotherapy and bone grafting. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1997 Jan:79(1):20-5 [PubMed PMID: 9020439]

Cottalorda J, Bourelle S. Modern concepts of primary aneurysmal bone cyst. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2007 Feb:127(2):105-14 [PubMed PMID: 16937137]

Park HY, Yang SK, Sheppard WL, Hegde V, Zoller SD, Nelson SD, Federman N, Bernthal NM. Current management of aneurysmal bone cysts. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2016 Dec:9(4):435-444 [PubMed PMID: 27778155]

Boubbou M, Atarraf K, Chater L, Afifi A, Tizniti S. Aneurysmal bone cyst primary--about eight pediatric cases: radiological aspects and review of the literature. The Pan African medical journal. 2013:15():111. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2013.15.111.2117. Epub 2013 Jul 28 [PubMed PMID: 24244797]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMascard E, Gomez-Brouchet A, Lambot K. Bone cysts: unicameral and aneurysmal bone cyst. Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research : OTSR. 2015 Feb:101(1 Suppl):S119-27. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2014.06.031. Epub 2015 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 25579825]

Lau AW, Pringle LM, Quick L, Riquelme DN, Ye Y, Oliveira AM, Chou MM. TRE17/ubiquitin-specific protease 6 (USP6) oncogene translocated in aneurysmal bone cyst blocks osteoblastic maturation via an autocrine mechanism involving bone morphogenetic protein dysregulation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010 Nov 19:285(47):37111-20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.175133. Epub 2010 Sep 23 [PubMed PMID: 20864534]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRossi G, Rimondi E, Bartalena T, Gerardi A, Alberghini M, Staals EL, Errani C, Bianchi G, Toscano A, Mercuri M, Vanel D. Selective arterial embolization of 36 aneurysmal bone cysts of the skeleton with N-2-butyl cyanoacrylate. Skeletal radiology. 2010 Feb:39(2):161-7. doi: 10.1007/s00256-009-0757-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19669138]

Papagelopoulos PJ, Currier BL, Shaughnessy WJ, Sim FH, Ebsersold MJ, Bond JR, Unni KK. Aneurysmal bone cyst of the spine. Management and outcome. Spine. 1998 Mar 1:23(5):621-8 [PubMed PMID: 9530795]

Aboulafia AJ, Kennon RE, Jelinek JS. Begnign bone tumors of childhood. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 1999 Nov-Dec:7(6):377-88 [PubMed PMID: 11505926]

Levine SM, Lambiase RE, Petchprapa CN. Cortical lesions of the tibia: characteristic appearances at conventional radiography. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2003 Jan-Feb:23(1):157-77 [PubMed PMID: 12533651]

Biermann JS. Common benign lesions of bone in children and adolescents. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2002 Mar-Apr:22(2):268-73 [PubMed PMID: 11856945]

Amelio JM, Rockberg J, Hernandez RK, Sobocki P, Stryker S, Bach BA, Engellau J, Liede A. Population-based study of giant cell tumor of bone in Sweden (1983-2011). Cancer epidemiology. 2016 Jun:42():82-9. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2016.03.014. Epub 2016 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 27060625]

Murphey MD, Nomikos GC, Flemming DJ, Gannon FH, Temple HT, Kransdorf MJ. From the archives of AFIP. Imaging of giant cell tumor and giant cell reparative granuloma of bone: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2001 Sep-Oct:21(5):1283-309 [PubMed PMID: 11553835]

Copley L, Dormans JP. Benign pediatric bone tumors. Evaluation and treatment. Pediatric clinics of North America. 1996 Aug:43(4):949-66 [PubMed PMID: 8692589]

Struhl S, Edelson C, Pritzker H, Seimon LP, Dorfman HD. Solitary (unicameral) bone cyst. The fallen fragment sign revisited. Skeletal radiology. 1989:18(4):261-5 [PubMed PMID: 2781324]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEnneking WF. A system of staging musculoskeletal neoplasms. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1986 Mar:(204):9-24 [PubMed PMID: 3456859]

Vergel De Dios AM, Bond JR, Shives TC, McLeod RA, Unni KK. Aneurysmal bone cyst. A clinicopathologic study of 238 cases. Cancer. 1992 Jun 15:69(12):2921-31 [PubMed PMID: 1591685]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence