Introduction

Actinomycosis is a rare subacute to chronic infection caused by the gram-positive filamentous non-acid fast anaerobic to microaerophilic bacteria, Actinomyces. The infection is usually a granulomatous and suppurative infection. The chronic form has multiple abscesses that form sinus tracts and are associated with sulfur granules. About 70% of infections are due to either Actinomyces israelii or Actinomyces gerencseriae.

The diagnosis can be difficult, as isolation of the organism requires prolonged bacterial culture under anaerobic conditions. The infection is usually polymicrobial and very rarely spreads hematogenously. The other organisms which are usually associated with the infection are Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Prevotella, Streptococcus, Enterobacteriaceae, Peptostreptococcus, and Staphylococcus.[1][2][3]

The bacteria infects by inhibiting host defenses and/or reducing partial pressures of oxygen.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Actinomyces normally colonize the human mouth, urogenital tract, and gastrointestinal (GI) tract. As it is a commensal organism, it is very difficult to determine normal flora colonization versus infection.[4][5][6]

Thoracic actinomycosis may occur in patients with alcohol use disorder and seizure disorders. Pulmonary infection usually occurs as a complication of aspiration. Rarely disease can result from a human bite. Infection in the cervical and facial areas typically occurs following oral cavity surgery in patients with poor oral hygiene. Pelvic actinomycosis has been associated with the use of intrauterine devices (IUDs). Abdominal actinomycosis has been reported after any abdominal surgery but is most commonly seen after an appendectomy.

Epidemiology

The incidence of the disease is greater in males age 20 to 60 years with a peak incidence in 40 to 50 years. The male to female ratio for incidence is 3:1. The use of IUD contraceptive devices in females has increased the incidence. The infection has a higher prevalence within areas with low socioeconomic status. There is no racial predilection.[7]

Pathophysiology

Actinomyces are part of the normal flora of the human oral cavity, GI tract, and female urogenital tract. The organism is not virulent and only invades the body to cause deeper infections when there is tissue injury and a subsequent break in the normal mucosal barrier. Infection is mostly polymicrobial, with as many as 5 to 10 other bacterial species present. The infection is established with the help of a companion bacteria by inhibiting host defenses, reducing oxygen tension, or by producing a toxin that facilitates the inoculation of actinomycoses. [8][9][10]

Once mucosal barriers are breached, and infection is established, the human host responds by initiating an intense inflammatory response which is suppurative and granulomatous. The infection does not respect tissue planes and spreads contiguously. This results in draining sinus tracts, tiny yellow clumps called sulfur granules, and the result may be intense fibrosis of tissue.

Around 60% of infections are cervicofacial and described as “lumpy jaw syndrome.” The predisposing risk factors for cervicofacial infection include infection in erupting teeth, dental caries, gingivitis, and dental extraction, diabetes, alcohol use disorder, malnutrition, and malignancy.

HIV, solid organ transplantation of lungs or kidneys, biologic agents like infliximab, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with chemotherapy are other risk factors.

Pulmonary infections are primarily due to the aspiration of oral and GI secretions. Risk factors include the diseases mentioned above, as well as any chronic lung disease that lead to tissue destruction and break in normal mucosal defenses such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchiectasis, tuberculosis (TB), silicosis, among others. It can be a direct or indirect extension from a cervicofacial infection. From the lungs, Actinomyces can easily spread to mediastinum and pleura. Bronchial and laryngeal infections are rare. Vocal cord infection may mimic cancer.

The second most frequent site for Actinomyces infection is the genitourinary tract. The primary risk factor is the use of the intrauterine device.

Abdominal actinomycosis is most common in the appendix, cecum, and colon. Abdominal surgery is the most significant risk factor.

Skin and soft tissue actinomycosis is rare but can occur secondary to skin injury.

Hematogenous dissemination is extremely rare.

Histopathology

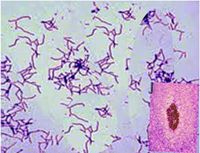

Gram staining of infected tissue or purulent material is more useful and sensitive than culture, as, in 50% of cases, culture may be negative. The negative rate is high due to previous antibiotic therapy, polymicrobial infection where other organisms present inhibit growth, failure to maintain an anaerobic environment during transportation and culture, or short-term incubation. [11]

The characteristic of the disease is the yellow sulfur granules. They are formed primarily by mycelial fragments with some proteinaceous polysaccharide complexes, which act as a resistance mechanism to avoid and inhibit phagocytosis. The most common microscopic finding is necrosis of yellowish sulfur granules and the filamentous gram-positive bacteria. The most appropriate specimen is a tissue biopsy of the infected site or pus. For better results, the clinician should note their suspicion for the infection to the microbiologist or pathologist. This will ensure anaerobic cultures are performed for prolonged time frames to ensure an optimal growth environment. [12]

Immunofluorescence has poor sensitivity but high specificity and can be used to confirm the diagnosis. [13]

History and Physical

The clinical presentation depends upon the site of infection and can vary accordingly. Taking a detailed history, which includes risk factors, is essential. [14][15]

Cervicofacial

This is the most common, constituting approximately 60% of infections and usually involves the tissues surrounding the maxilla and lower mandible (almost 50% of all cases). The most common presentation is a progressive, painless mass that is indurated with or without reddish or bluish discoloration of overlying skin and eventually evolves into multiple abscesses with sinus tract formation, which drains yellow sulfur granules. The patient may give a history of an oral procedure or injury. Difficulty in chewing food and trismus can occur in chronic stages of infection. Lymphadenopathy is not associated with the disease process.

Genitourinary

History of IUD use is common. The symptoms mostly mimic gynecological tumors, both malignant and benign. The presentation could be with lower abdominal pain, constipation, and vaginal discharge. Fever is rare unless the disease spreads to the peritoneum.

GI

The patient might have a history of abdominal surgery, especially appendectomy, perforated viscus, or ingestion of a fish bone. It can involve the esophagus, appendix, cecum, and colon, and presentation depends upon the site of infection. In esophageal disease, dysphagia is the most common symptom. At other gastrointestinal sites, the infection presents with nonspecific symptoms of low-grade fever, weight loss, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, change in bowel habits, and abdominal pain with or without a palpable mass. Rarely, the liver and biliary tract are involved, in which case, there may be right upper quadrant pain and jaundice.

Pulmonary

The infection can be acute to subacute, but because the diagnosis is difficult most cases are diagnosed in the chronic phase. Initially, the patients may present with very nonspecific symptoms of mild fever and weight loss. The symptoms mimic other chronic lung infections and cancer. The most common symptoms are a chronic productive cough with or without hemoptysis, shortness of breath, and chest pain. Lung parenchymal infections can cavitate, forming sinus tracts, which are a pathognomonic finding. If the disease process is extensive, and the host is immunocompromised, the disease process can present with severe hypoxemia and florid respiratory failure with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Evaluation

A complete blood count (CBC) will show leukocytosis with elevated neutrophils. Nonspecific inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate are elevated.[16][17][18]

The gold standard test for diagnosis is tissue biopsy culture with anaerobic pus cultures. Swabs from the infected sites should be avoided. Cultures can be falsely negative; gram-stain may demonstrate the presence of branched, beaded, gram-positive filamentous rods with sulfur granules, which helps in making a preliminary diagnosis. For examination, under the microscope, the granules should be crushed in between the two slides and then stained with methylene blue to identify the organism.

Serological tests do not help in making the diagnosis.

Imaging results will depend upon the site of infection and can mimic other chronic infections like nocardiosis, TB, and malignancy.

Cervicofacial

Imaging findings are nonspecific and are noncontributory in diagnosing the disease but will help in assessing the degree of soft tissue and bone involvement. Dental radiographs are helpful in evaluating the apical abscesses. CT and MRI studies may show osteolysis in the chronic form of infection.

Pulmonary

The imaging for actinomycosis is nonspecific. In the acute presentation, it can look like any other pneumonia. In chronic forms, it can present as a pulmonary mass or can cavitate. In the case of a mass malignancy, actinomycosis is an important diagnosis to consider. Especially when it cavitates, tuberculosis is an important differential diagnosis to consider. The computed tomography scan findings can vary depending upon the duration of illness and can include consolidation, cavitation, pleural effusion, lymph node enlargement, atelectasis, and ground glass opacification.

The gold standard test is a histological examination and bacterial culture of a biopsy, which can be obtained with bronchoscopy (pulmonologist), a CT-guided biopsy (interventional radiologist), or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) performed by a thoracic surgeon. Anaerobic cultures of pleural fluid rarely grow the organism. Sputum culture will not be useful unless the patient has a cavitary disease.

GI

Imaging of actinomycosis can be nonspecific; findings will depend upon the site of infection and chronicity. In chronic cases, a CT scan might show an enterocutaneous fistula with multiple abdominal abscesses. The best test is a culture of the infected site.

Genitourinary

A CT scan can show pelvic mass (6 to 7 cm) with the cystic lesion. Lymphadenopathy can be seen in 40% to 60% of cases. A tubo-ovarian abscess is highly suggestive of infection with actinomycosis. Bladder actinomycosis can present like bladder carcinoma, with bladder thickening and hematuria.

Pus samples can be taken after removing the IUD. Colonization must be differentiated from infection. Tissue biopsy should be taken in patients presenting with pelvic masses to rule out malignancy.

Treatment / Management

Most of the cases can be managed with antibiotics; surgery can be adjunctive.[19][20](A1)

Medical management in the form of antibiotics includes:

- Penicillin G

- Beta-lactams with a long course of oral amoxicillin

- Cephalosporin

If the patient is allergic to penicillin, alternatives include:

- Clindamycin

- Macrolides (erythromycin, clarithromycin or azithromycin)

- Doxycycline

A combination of metronidazole and a beta-lactamase inhibitor may be tried in polymicrobial infections.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing is not indicated due to predictable antibiogram.

The duration of therapy is usually 6 to 12 months but can be shortened if surgical resection of the infected site has been performed. Type of surgery will depend upon the site and extent of the disease, but it usually involves incision and drainage of abscesses, decompression of closed space, and excision of sinus tracts.

The response to treatment can be monitored with imaging.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential will depend upon the site of infection. It is a slow-spreading infection that can mimic benign or malignant tumors, nocardiosis, and TB.

The other important differential diagnosis to consider are the following:

- Aspiration pneumonia

- Appendicitis

- Diverticulosis

- Crohn disease

- Lung abscess

- Fungal pneumonia

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Brain abscess

- Dental abscess

Prognosis

Prolonged antibiotic therapy is usually required, and the prognosis is excellent. With better oral hygiene, availability of antibiotics, and advanced surgical techniques, the outcome, and mortality have improved. For extensive and complicated disease, antibiotics and surgical treatment are required. In these cases, morbidity is high, and death may occur.

Complications

Complications of actinomycosis include the development of abscesses and the spread of the infection. Osteomyelitis is a possible complication with the involvement of the ribs, vertebrae, and the mandible. Nervous system involvement will include meningitis, brain abscess, actinomycetoma, cranial, epidural and subdural infection, and spinal epidural infection.

In addition, other complications are hepatic actinomycosis, endocarditis, and disseminated actinomycosis.

Consultations

Actinomycosis is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes an infectious disease specialist, intensivist, general surgeon, endocrinologist, and an internist.

Pearls and Other Issues

Most patients need central catheters for prolonged intravenous (IV) antibiotics as outpatients. Repeat imaging is required to determine if the infection is resolving. The prognosis for most patients is good, but extensive scarring may be the result.

Good oral hygiene and limitation of alcohol may limit cervicofacial, pulmonary, and central nervous system (CNS) actinomycosis. In women, changing the IUD device every five years prevents actinomycosis infection.

Actinomyces infection has no racial predilection and is not contagious.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Actinomycosis infections are not common, but when they do occur, they are usually serious. The organism can infect almost any organ; thus, actinomycosis is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes an infectious disease consult, intensivist, general surgeon, endocrinologist, an internist, and a specialty trained infectious disease pharmacist. These patients need close monitoring by nurses because the infection can rapidly prove fatal in immunocompromised hosts or patients with diabetes. Pharmacists should assist with the coordination of antibacterial treatment and help the team avoid drug-drug interactions, monitor for drug therapy complications, and assist in educating the patient and family on medication compliance. The outcomes depend on the site of infection, its severity, patient immune status, and other comorbidities. In healthy people, the infection has low morbidity and mortality if treated.[21][22]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Seen from a medial view, the right leg of this patient in the region of the knee, displayed numerous cutaneous lesions that were diagnosed as the result of a disease process known as actinomycosis, or mycetoma, caused by the Gram-positive, fungus-like aerobic bacteria of the order Actinomycetales. Mycetoma is a slowly progressive, destructive infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues, fascia, and can progress to a point where it can affect bone as well. Contributed by the CDC/ Dr. Hardin

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Seen from the left lateral perspective, this female patient displayed a fistula that had formed on the region of her left cheek, which had been brought on by an infection known as actinomycosis, or mycetoma, caused by the Gram-positive, fungus-like aerobic bacteria of the order Actinomycetales. Mycetoma is a slowly progressive, destructive infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues, fascia, and can progress to a point where it can affect bone as well. Contributed by the CDC/ Dr. Robert Fass; Ohio State Dept. of Medicine

(Click Image to Enlarge)

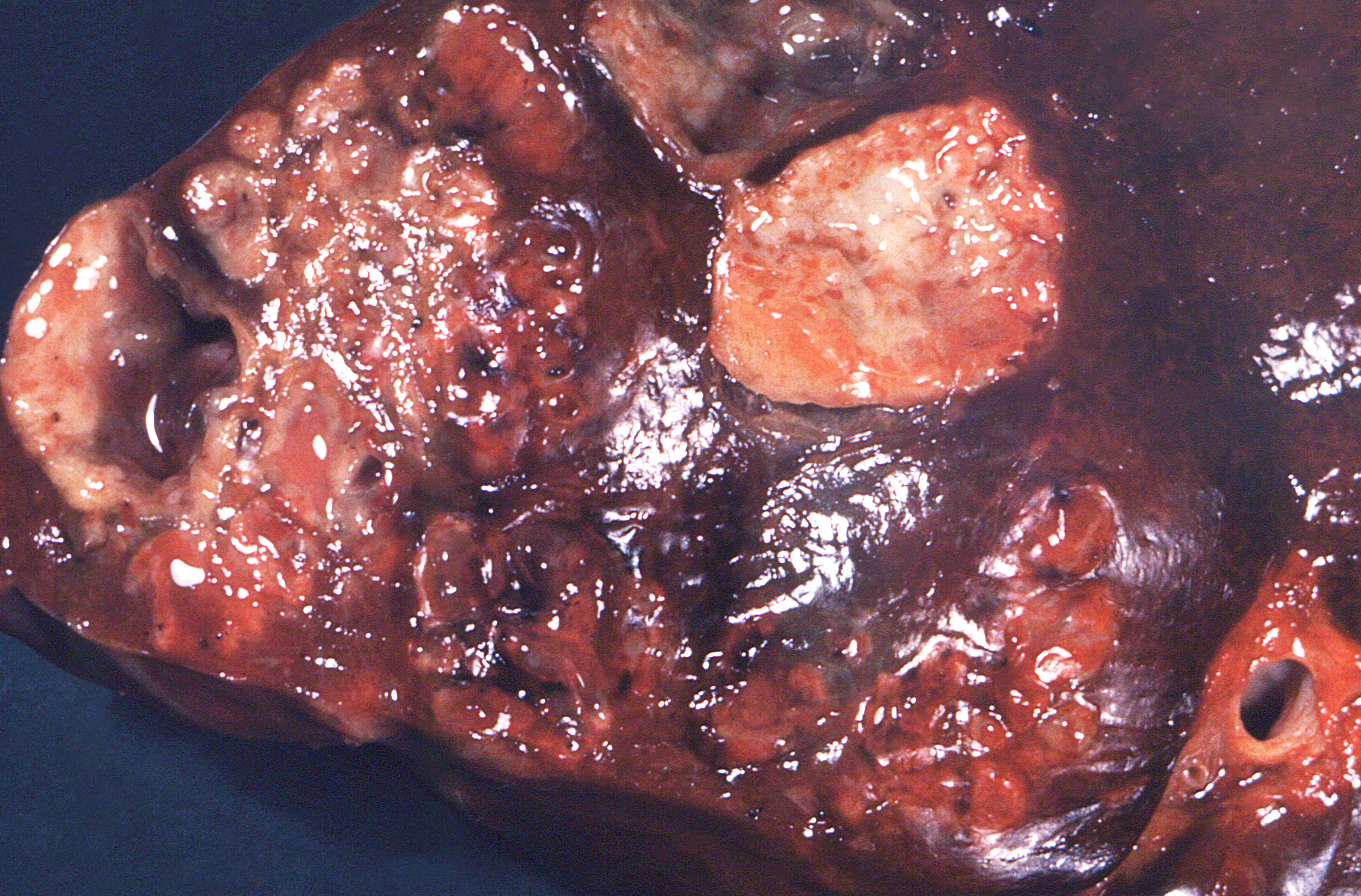

This cut section of human liver, revealed the presence of numerous suppurative, or pus containing lesions due to an infection known as actinomycosis, caused by the Gram-positive, fungus-like, aerobic bacteria of the order Actinomycetales. Actinomycosis, or mycetoma, is a slowly progressive, destructive infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues, fascia, and can progress to a point, where it can affect bone and other organs, including the liver, as in this case. Contributed by the CDC/ Dr. Lucille K. Georg

(Click Image to Enlarge)

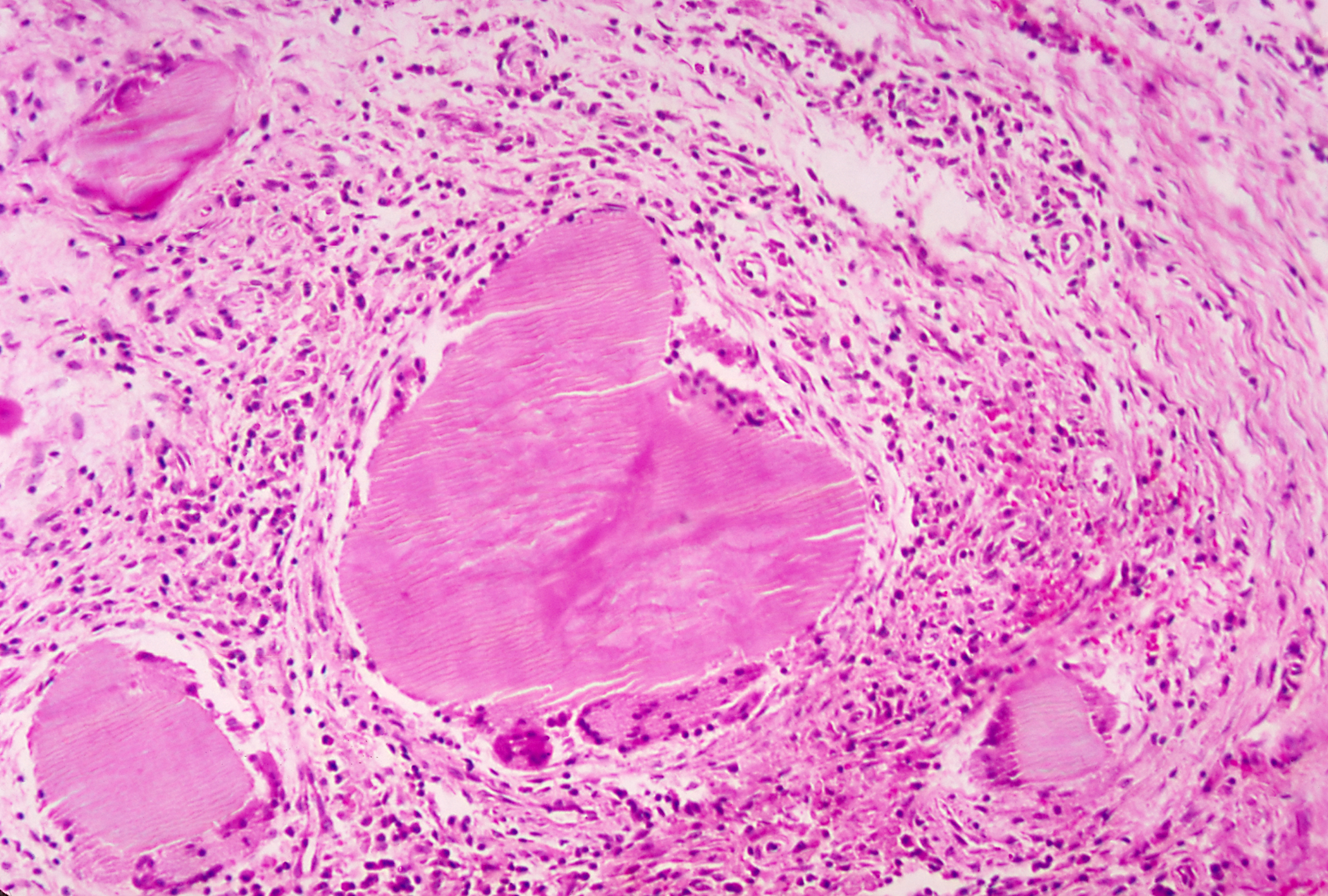

Under a magnification of 200X, this photomicrograph of a Gram-stained brain tissue specimen, revealed the presence of a chronic inflammatory sulfur granule in a case of actinomycosis, caused by a Gram-positive, fungus-like aerobic bacterium of the genus, Actinomyces. Contributed by the CDC/ Dr. Richard L. Levin, Greater Southeast Community Hospital, Washington, D.C.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

This image depicts a right lateral view of a patient’s head and neck, revealing a cutaneous lesion, just anterior to the right ear, which was determined to be a case of actinomycosis. Actinomyces spp., normally found in the oral cavity, can become an opportunistic pathogen, a situation usually seen only in immunosuppressed patients. Lesions involve long-standing swelling, suppuration and the formation of an abscess or granuloma. Contributed by the CDC/ Dr. Thomas F. Sellers; Emory University

(Click Image to Enlarge)

This photomicrograph of an unidentified tissue specimen was harvested from a patient, who had presented with a case of actinomycosis, caused by the Gram-positive, aerobic actinomycete, Streptomyces somaliensis. Note the number of characteristic sulfur granules visible in this view. Contributed from the CDC

References

Ahmed S, Ali M, Adegbite N, Vaidhyanath R, Avery C. Actinomycosis of tongue: Rare presentation mimicking malignancy with literature review and imaging features. Radiology case reports. 2019 Feb:14(2):190-194. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2018.10.022. Epub 2018 Nov 8 [PubMed PMID: 30425772]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTippett E, Goyal N, Guy S, Wong J. Actinomyces spp. bloodstream and deep vein thrombus infections in people who inject drugs. Infection. 2019 Jun:47(3):479-482. doi: 10.1007/s15010-018-1246-x. Epub 2018 Nov 8 [PubMed PMID: 30406927]

Mishra A, Prabhuraj AR, Bhat D, Nandeesh BN, Mhatre R. Intracranial Actinomycosis Manifesting as a Parenchymal Mass Lesion: A Case Report and Review of Literature. World neurosurgery. 2019 Feb:122():190-194. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.10.134. Epub 2018 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 30391617]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcCann A, Alvi SA, Newman J, Kakarala K, Staecker H, Chiu A, Villwock JA. Atypical Form of Cervicofacial Actinomycosis Involving the Skull Base and Temporal Bone. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2019 Feb:128(2):152-156. doi: 10.1177/0003489418808541. Epub 2018 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 30371104]

Valdés-Peregrina EN, Bonifaz A, Arteaga-Sarmiento JF, Hernández-González M. [Primary intestinal actinomycosis in ilium and colon. A case report and review of the literature]. Revista espanola de patologia : publicacion oficial de la Sociedad Espanola de Anatomia Patologica y de la Sociedad Espanola de Citologia. 2018 Oct-Dec:51(4):253-256. doi: 10.1016/j.patol.2017.10.005. Epub 2017 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 30269778]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSadeghi S, Azaïs M, Ghannoum J. Actinomycosis Presenting as Macroglossia: Case Report and Review of Literature. Head and neck pathology. 2019 Sep:13(3):327-330. doi: 10.1007/s12105-018-0966-7. Epub 2018 Sep 22 [PubMed PMID: 30244331]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRolfe R, Steed LL, Salgado C, Kilby JM. Actinomyces meyeri, a Common Agent of Actinomycosis. The American journal of the medical sciences. 2016 Jul:352(1):53-62. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.03.003. Epub 2016 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 27432035]

Gomes-Silva W, Pereira DL, Fregnani ER, Almeida OP, Armada L, Pires FR. Clinicopathological and ultrastructural characterization of periapical actinomycosis. Medicina oral, patologia oral y cirugia bucal. 2020 Jan 1:25(1):e131-e136. doi: 10.4317/medoral.23247. Epub 2020 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 31880281]

Ge MJ, Fu YQ, Zhou H, Wang J, Zhou JY. [Clinical feature analysis of 30 cases with pulmonary actinomycosis]. Zhonghua yi xue za zhi. 2019 Dec 10:99(46):3617-3621. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2019.46.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31826582]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePalm A, Isaksson J, Brandén E, Hillerdal G. [Thoracal actinomycosis - a diagnostic challenge]. Lakartidningen. 2019 Dec 3:116():. pii: FR6A. Epub 2019 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 31821519]

Urs AB, Augustine J, Singh S. Histopathological evaluation of a rare fulminant case of contemporaneous mucormycosis, aspergillosis and actinomycosis. Journal of oral and maxillofacial pathology : JOMFP. 2019 Jan-Apr:23(1):144-146. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_64_19. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31110432]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcHugh KE, Sturgis CD, Procop GW, Rhoads DD. The cytopathology of Actinomyces, Nocardia, and their mimickers. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2017 Dec:45(12):1105-1115. doi: 10.1002/dc.23816. Epub 2017 Sep 9 [PubMed PMID: 28888064]

Leslie DE, Garland SM. Comparison of immunofluorescence and culture for the detection of Actinomyces israelii in wearers of intra-uterine contraceptive devices. Journal of medical microbiology. 1991 Oct:35(4):224-8 [PubMed PMID: 1941993]

Stabrowski T, Chuard C. [Actinomycosis]. Revue medicale suisse. 2019 Oct 9:15(666):1790-1794 [PubMed PMID: 31599519]

Duldulao PM, Ortega AE, Delgadillo X. Mycotic and Bacterial Infections. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2019 Sep:32(5):333-339. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1687828. Epub 2019 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 31507342]

Ding X, Sun G, Fei G, Zhou X, Zhou L, Wang R. Pulmonary actinomycosis diagnosed by transbronchoscopic lung biopsy: A case report and literature review. Experimental and therapeutic medicine. 2018 Sep:16(3):2554-2558. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6483. Epub 2018 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 30186488]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLim JA, Wong PS, Leong KN, Wong KL, Chow TS. Masking and misleading: concomitant actinomycosis and B-cell lymphoma - a case report and review of literature. Scottish medical journal. 2018 Aug 30:():36933018789312. doi: 10.1177/0036933018789312. Epub 2018 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 30165794]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRousseau C, Piroth L, Pernin V, Cassuto E, Etienne I, Jeribi A, Kamar N, Pouteil-Noble C, Mousson C. Actinomycosis: An infrequent disease in renal transplant recipients? Transplant infectious disease : an official journal of the Transplantation Society. 2018 Dec:20(6):e12970. doi: 10.1111/tid.12970. Epub 2018 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 30055044]

Steininger C, Willinger B. Resistance patterns in clinical isolates of pathogenic Actinomyces species. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2016 Feb:71(2):422-7. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv347. Epub 2015 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 26538502]

Nelson AL, Sulak P. IUD patient selection and practice guidelines. Dialogues in contraception. 1998 Spring:5(5):7-12 [PubMed PMID: 12321491]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRavindra N, Sadashiva N, Mahadevan A, Bhat DI, Saini J. Central Nervous System Actinomycosis-A Clinicoradiologic and Histopathologic Analysis. World neurosurgery. 2018 Aug:116():e362-e370. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.04.205. Epub 2018 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 29751182]

Hwang CS, Lee H, Hong MP, Kim JH, Kim KS. Brain abscess caused by chronic invasive actinomycosis in the nasopharynx: A case report and literature review. Medicine. 2018 Apr:97(16):e0406. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010406. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29668598]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence