Introduction

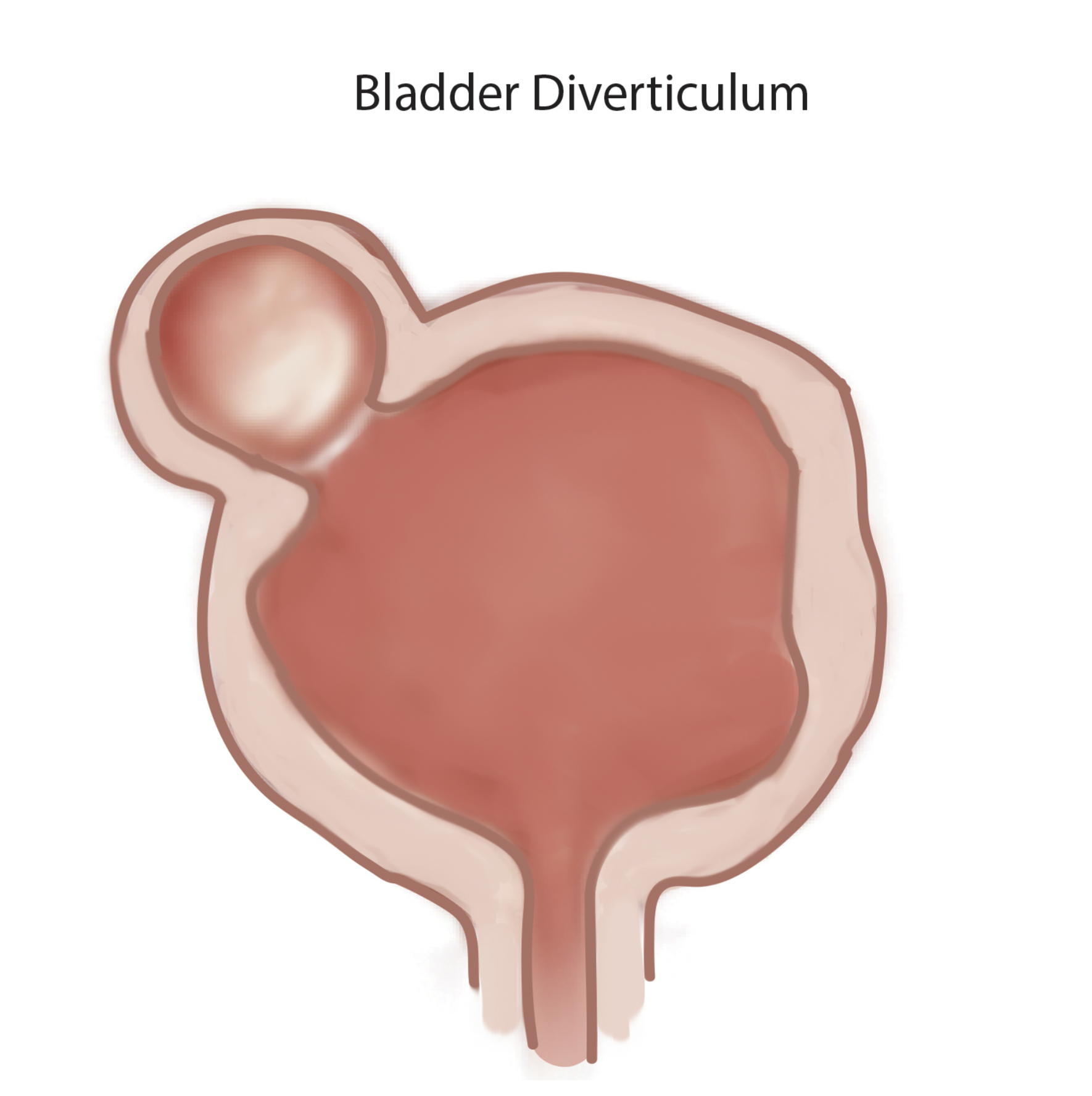

Bladder diverticula are protrusions of the bladder urothelium and mucosa via muscle fibers of the bladder wall, the muscularis propria, which results in a thin-walled structure connected to the bladder lumen and poorly empties during micturition. Bladder diverticula occur either to congenital or acquired causes. They affect both adults and children. Unlike the acquired adult form, in which outlet obstruction or neurogenic dysfunction is virtually usually present, congenital bladder diverticula arise from hypoplasia of the muscular layer of the bladder wall.[1][2]

They tend to be more prevalent in adults and affect males more than females.[3] In the majority of the cases, they have positioned superolateral to the ureteral orifice close to the ureterovesical junction. Bladder diverticula usually display as incidental anomalies on imaging following evaluation of hematuria, lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), or infection.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Bladder diverticula seem to be either congenital or acquired. Their clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and imaging studies can differentiate those two different categories. The frequency of congenital bladder diverticula is estimated to be 1.7 percent and increases in children below ten.[4] Those usually are singular and affect males. In addition, the majority are positioned superolateral to the ureteral orifice in the vicinity of the ureterovesical junction and associated with vesicoureteral reflux.[5][1]

In comparison to adults, among whom coexistent lower urinary tract neurogenic disorder or obstruction is almost always present, the predominant causation in the pediatric age group is usually considered to be a congenital weakness of the detrusor muscle, often at the point of the ureterovesical junction.[3]

The acquired type often develops in males above the age of 60, and those diverticula are commonly found along the lateral wall of the bladder. Similar to the mechanism in infants with posterior urethral valves, it is assumed that the pressure within the bladder increases from other underlying conditions, such as prostatic disease or neurological disorders. An increase in the intravesical pressure leads the urinary bladder mucosa to insert itself between muscle bundles, creating a mucosal extravasation sac which further culminates in the formation of diverticula.[6]

Epidemiology

Bladder diverticula can occur in adults or children; however, compared to the rest, 90 percent of bladder diverticula affect adults. In addition, these lesions are significantly more prevalent in males than females, with a frequency of around 9 to 1 in the adult and pediatric age ranges.[3][7]

Pathophysiology

The bladder wall, which consists of three interlacing muscle layers, prevents bladder herniation during any sudden rise of the intracystic pressure. Any disturbances in its arrangement or composition will lead to the development of the bladder diverticulum. Several congenital syndromes have been linked to the development of bladder diverticula, such as Menkes syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and fetal alcohol syndrome. They usually present with multiple lesions, and chromosomal testing is advised.[8][9]

On the other hand, acquired bladder diverticulum is caused by a bladder outlet obstruction, whether it is due to benign or malignant causes. These include prostate conditions, bladder neck hypertrophy, and urethral stricture.

Histopathology

The bladder diverticulum wall histologically is formed of the bladder mucosa, part of the subepithelial connective tissue, part of the thin muscle fibers, and the adventitial layer. An outer shell composed of a fibrous capsule is present most of the time, and it acts as a surgical plane to help dissect it. Other common findings may include inflammatory process, a degree of erosion, and granulation tissue formation.[10]

History and Physical

Bladder diverticula do not often create distinct symptoms and are most commonly detected accidentally in investigating another unrelated ailment, including urinary tract infections. Because large bladder diverticula empty slowly or incompletely after voiding, symptoms and indications, if present, are frequently attributed to urine stasis inside the diverticulum or, potentially, to its mass effect in the lower abdominal area.

Retrospectively, when probed, patient complaints such as inadequate bladder emptying, lower abdominal fullness, and double voiding may be linked to certain major bladder diverticula. These symptoms, however, are vague and might be caused to prostatic growth, blockage, or a variety of other lower urinary tract disorders. The most frequent manifestation of congenital bladder diverticula is acute urinary tract infection arising from stasis. Less common presentations manifest as hematuria, abdominal discomfort, or a palpable abdominal mass.[11][12]

Evaluation

A bladder diverticulum is suspected in all patients with symptoms such as recurrent infection, dysuria, and abdominal distension, suggesting bladder outlet obstruction and urinary retention. The initial evaluation of the bladder diverticulum requires a thorough medical history and physical examination, including a digital rectal examination. For men, prostate-specific antigen testing is done. The medical record should quantify the lower urinary tract to help reveal potential hidden neurological causes and any previous lower urinary tract surgery.

Urine analysis, urine culture, and urine cytology should be performed in most patients with bladder diverticula, especially when nonoperative therapy is explored. The urine abnormalities are prevalent in those patients where pyuria and hematuria are commonly found.

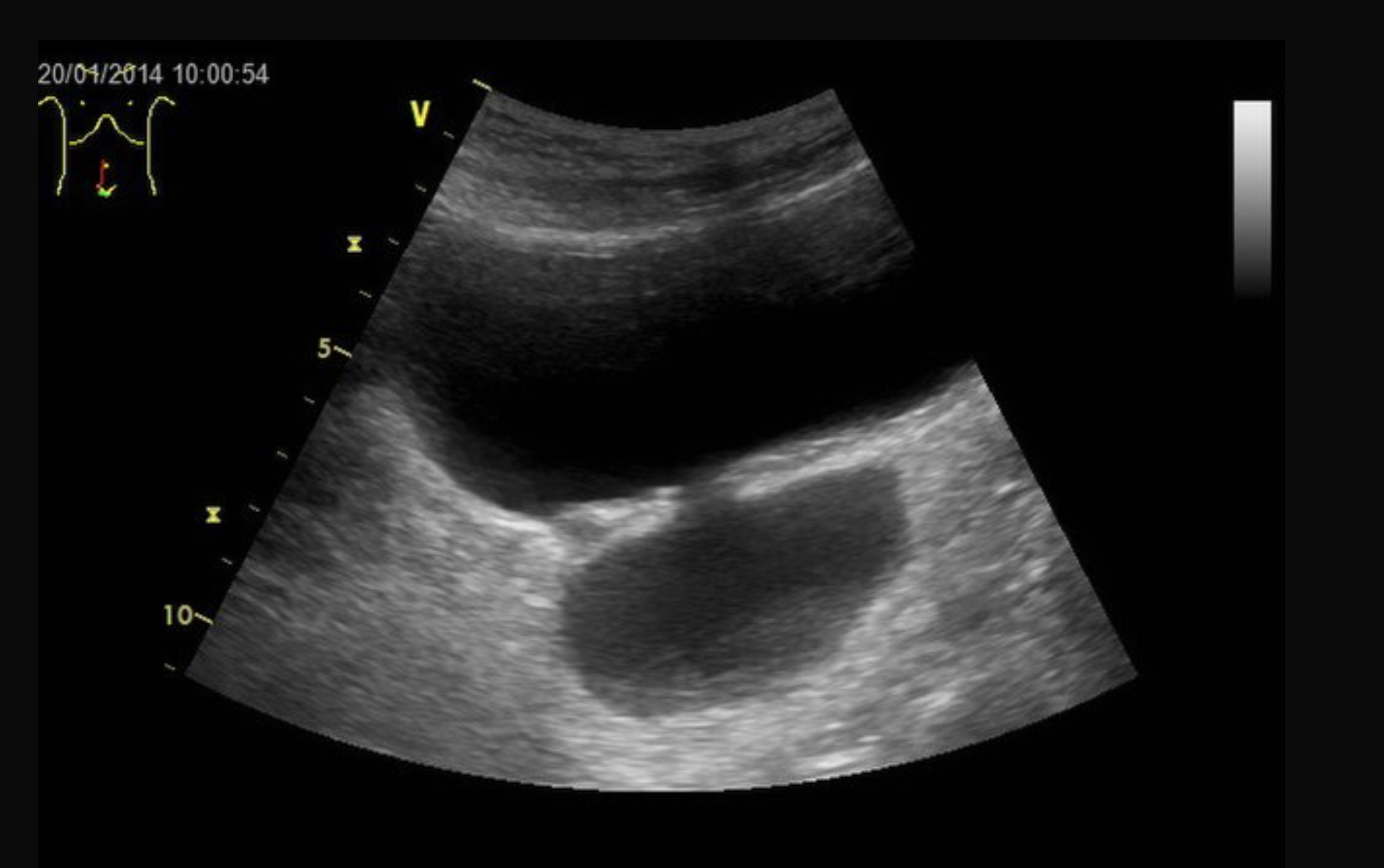

Radiographic and endoscopic results are primarily used to diagnose bladder diverticula. They are frequently discovered by chance during a radiographic evaluation and study of recurrent urinary tract infections or other non-specific lower urinary symptoms or signs. Fluoroscopically monitored voiding cystourethrography is a good test for detecting bladder diverticula because it provides information about the diverticulum's location, anatomy, and size. Other imaging modalities, such as cross-sectional imaging of the lower urinary system, aid in diagnosing bladder diverticula. Diverticula can be detected through endoscopic examination of the bladder. The entire diverticula should be checked for any stones or aberrant epithelium during this procedure.[13]

Treatment / Management

Bladder diverticula can be addressed through conservative nonoperative therapy, surgical excision, and endoscopic care. Indications for treating bladder diverticula include urinary infection, stones, or cancer. Malignancy can be of particular concern related to bladder diverticula due to the lack of a muscle wall beyond the mucosal layer, resulting in a higher risk for extension of possible malignancy outside the bladder.[14] Open bladder diverticulectomy is the most invasive treatment method and can be done either by an intra-vesical or extravesical technique.[15]

Adults with minor or no symptoms and no aggravating conditions may offer monitoring and surveillance. These people should be warned about the possibility of increased cancer risk and what red flags to be aware of, such as haematuria, dysuria, and other lower urinary tract symptoms. Unfortunately, the length and scheduling of those assessments are poorly defined, but they consist of regular reviews of symptoms, urine investigation including cytology, and regular cystoscopy exams. There is a role for clean intermittent catheterization in patients who cannot proceed with the surgical removal of the diverticulum or those who remain symptomatic despite the relief of obstruction.

Bladder diverticulectomy is usually done as an elective case. Surgery is generally indicated as described above when the bladder diverticulum becomes symptomatic. Most of the time, those symptoms are related to the poor emptying function of the diverticulum and urinary stasis. A detailed preoperative assessment is taken before surgery to decide the suitability of treatment for each individual.

The current minimal invasive treatment options available for diverticula removal are endoscopic resection, injecting bulking agents at the neck of the bladder, and fulguration.

For patients who are frail and not fit for prolonged surgery, endoscopic management of the diverticulum is considered. Multiple articles and reports in the literature have discussed and described those managements, including transurethral endoscopic fulguration of the bladder and transurethral resection of the diverticular neck, and fulguration of the mucosa of the diverticulum.[16]

Diverticulectomy can be done open, laparoscopically, or using a robot. Extraperitoneal or intraperitoneal approaches to the open abdomen are both possible. For modest diverticula, a transvesical technique can be utilized, in which the anterior portion of the bladder wall is opened. Then the diverticulum is everted and circumcised, and then the bladder is closed. A dual approach of transvesical and extravesical can be used if the diverticulum is large or adherent to the surrounding structures; after entering the bladder and identifying the diverticulum, the diverticulum is equipped with gauze and mobilized, then extravesical circumcision of the bladder neck is performed.[17][18][19](B2)

Intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal laparoscopic diverticulectomy is possible, albeit the extraperitoneal method is more difficult. Concurrent flexible cystoscopy can aid in locating the diverticulum's neck. Compared to the open technique, laparoscopic diverticulectomy has been linked to a shorter hospital stay and a lower requirement for analgesics, despite being a technically complex treatment with a higher mean operating time.[20] (B2)

Myer and Wagner published the first series of robot-assisted diverticulectomy (RAD) in 2007 and found that RAD had equivalent results to laparoscopic techniques, with a mean hospital stay of 2.4 days.[18][21] (B2)

Ergonomics, 3D visualization, dexterity, and precision are all improved with RAD. Obese people may benefit most from the robotic technique. In children, the reasons for bladder diverticulectomy are identical to those in adults. Because of the inherent connective tissue disorders found in these patients, which affect the postsurgical healing process, increase perioperative surgical risk, and predispose to recurrence, observation and medical management are usually preferred in children with multiple bladder diverticula associated with a chromosomal syndrome.

Differential Diagnosis

Bladder diverticula are often discovered accidentally during a radiological examination and appear as a fluid-filled formation near the bladder. The following are examples of differential diagnoses for such structures:

- Uterine, ovarian, and fallopian tube anomalies

- Urachal cysts

- Ectopic ureter

- Ureterocoele

- Mullerian cysts

- Post-surgical changes such as lymphocele[22]

Surgical Oncology

Unfortunately, bladder tumors within the bladder diverticulum are accountable for 2 to 10% of all tumors that arise in the bladder. Low-grade Ta/T1 tumors can be managed with transurethral resection. If carcinoma in situ (CIS) presents, adjuvant intravesical chemotherapy or bacillus Calmette-Guérin immunotherapy should be added.[24] Another more aggressive approach includes either diverticulectomy or partial cystectomy.

Patients with locally progressed tumors, high-grade tumors in the diverticulum, simultaneous intravesical multifocal ulcerated tumors or widespread CIS, or multifocal disease coupled with impaired bladder function will benefit from radical cystectomy. Radical cystectomy is carried on open, laparoscopically, or robotically, with urine diversion determined by the needs and preferences of each patient. On the other hand, Radical cystectomy is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, and the requirement for urine diversion can significantly influence a patient's quality of life.[23][24][25]

Prognosis

Often, treatment is effective and may alleviate your symptoms. In some cases, after your diverticulum is treated (for instance, if a blockage in the bladder is corrected), you will not need any more treatment. A cystoscope may be used to examine your diverticulum through the urethra.

Complications

The stone formation, urinary tract infection (UTI), and malignancies can be caused by urine stasis in the diverticula, leading to chronic inflammation. The overall occurrence of tumors in the diverticula ranges from 2 to 10%, and the prognosis is usually poor due to the lack of a smooth muscle layer. The lack of the muscularis propria layer may predispose interdiverticular tumors to bladder wall infiltration and possible dissemination to other organs in principle; nevertheless, the aggressiveness of these tumors, their likelihood of spreading, and their clinical consequences are all uncertain.[26][27]

Urothelial cell carcinoma is the most common kind of cancer in those diverticula, preceded by squamous cell carcinoma. Usually, those patients' age is between 65 and 75.[28]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Once a patient has been diagnosed with bladder diverticulum, the likelihood of getting malignancies and lower urinary infections is increased. Thus it is vital to counsel those patients and discuss the importance of frequent follow-ups and reassessment. Also, they ought to be aware of the symptoms and the red flags, which include increasing in lower urinary tract symptoms and blood in the urine.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Bladder diverticulum, as mentioned early, has no unique presentation and is usually discovered incidentally; it has the potential to develop into bladder cancer which generally requires a medical and surgical intervention that will cause significant morbidity or even mortality. Thus any suspicious lower urinary tract symptoms, mainly hematuria, should be referred to a specialist for further evaluation.

Media

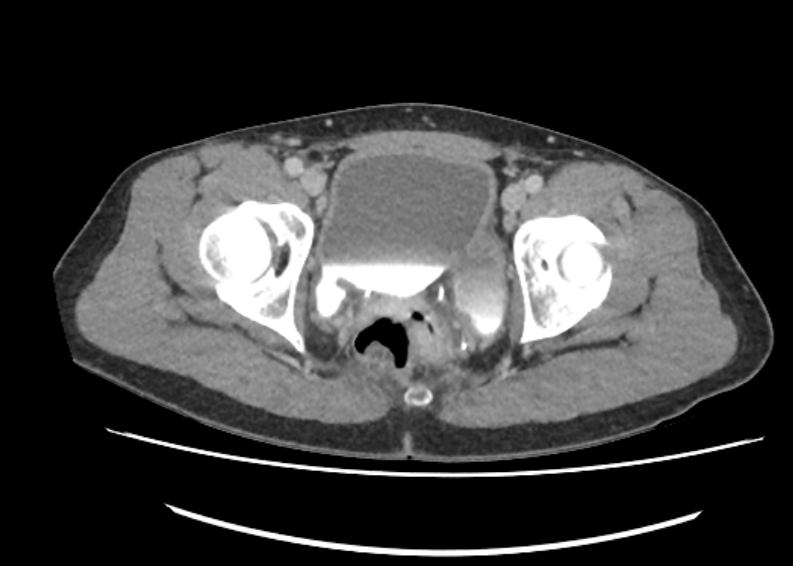

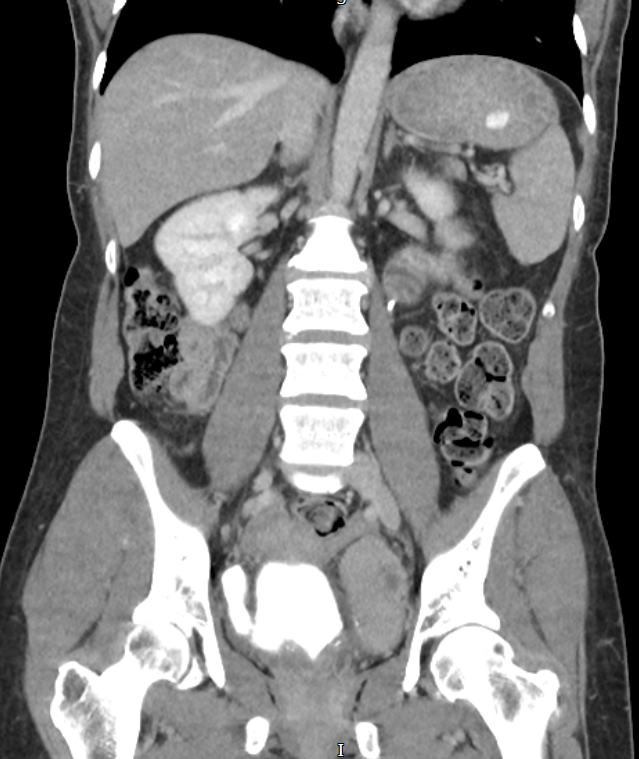

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Garat JM, Angerri O, Caffaratti J, Moscatiello P, Villavicencio H. Primary congenital bladder diverticula in children. Urology. 2007 Nov:70(5):984-8 [PubMed PMID: 18068458]

Abou Zahr R, Chalhoub K, Ollaik F, Nohra J. Congenital Bladder Diverticulum in Adults: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case reports in urology. 2018:2018():9748926. doi: 10.1155/2018/9748926. Epub 2018 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 29568661]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePsutka SP, Cendron M. Bladder diverticula in children. Journal of pediatric urology. 2013 Apr:9(2):129-38. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.02.013. Epub 2012 May 30 [PubMed PMID: 22658330]

Blane CE, Zerin JM, Bloom DA. Bladder diverticula in children. Radiology. 1994 Mar:190(3):695-7 [PubMed PMID: 8115613]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBoechat MI, Lebowitz RL. Diverticula of the bladder in children. Pediatric radiology. 1978 Apr 10:7(1):22-8 [PubMed PMID: 417286]

Gerridzen RG, Futter NG. Ten-year review of vesical diverticula. Urology. 1982 Jul:20(1):33-5 [PubMed PMID: 6810528]

Idrees MT, Alexander RE, Kum JB, Cheng L. The spectrum of histopathologic findings in vesical diverticulum: implications for pathogenesis and staging. Human pathology. 2013 Jul:44(7):1223-32. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.11.005. Epub 2013 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 23375647]

Hebert KL, Martin AD. Management of Bladder Diverticula in Menkes Syndrome: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Urology. 2015 Jul:86(1):162-4. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.03.030. Epub 2015 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 26051840]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBurrows NP, Monk BE, Harrison JB, Pope FM. Giant bladder diverticulum in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type I causing outflow obstruction. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 1998 May:23(3):109-12 [PubMed PMID: 9861737]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMelekos MD, Asbach HW, Barbalias GA. Vesical diverticula: etiology, diagnosis, tumorigenesis, and treatment. Analysis of 74 cases. Urology. 1987 Nov:30(5):453-7 [PubMed PMID: 3118548]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEvangelidis A, Castle EP, Ostlie DJ, Snyder CL, Gatti JM, Murphy JP. Surgical management of primary bladder diverticula in children. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2005 Apr:40(4):701-3 [PubMed PMID: 15852283]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePieretti RV, Pieretti-Vanmarcke RV. Congenital bladder diverticula in children. Journal of pediatric surgery. 1999 Mar:34(3):468-73 [PubMed PMID: 10211656]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHernanz-Schulman M,Lebowitz RL, The elusiveness and importance of bladder diverticula in children. Pediatric radiology. 1985; [PubMed PMID: 3932949]

Clayman RV, Shahin S, Reddy P, Fraley EE. Transurethral treatment of bladder diverticula. Alternative to open diverticulectomy. Urology. 1984 Jun:23(6):573-7 [PubMed PMID: 6428024]

Bogdanos J, Paleodimos I, Korakianitis G, Stephanidis A, Androulakakis PA. The large bladder diverticulum in children. Journal of pediatric urology. 2005 Aug:1(4):267-72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2005.01.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18947550]

Pham KN, Jeldres C, Hefty T, Corman JM. Endoscopic Management of Bladder Diverticula. Reviews in urology. 2016:18(2):114-7. doi: 10.3909/riu0701. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27601971]

Hickling DR, Sun TT, Wu XR. Anatomy and Physiology of the Urinary Tract: Relation to Host Defense and Microbial Infection. Microbiology spectrum. 2015 Aug:3(4):. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.UTI-0016-2012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26350322]

Myer EG, Wagner JR. Robotic assisted laparoscopic bladder diverticulectomy. The Journal of urology. 2007 Dec:178(6):2406-10; discussion 2410 [PubMed PMID: 17937944]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceThüroff JW, Roos FC, Thomas C, Kamal MM, Hampel C. Surgery illustrated--surgical Atlas: Robot-assisted laparoscopic bladder diverticulectomy. BJU international. 2012 Dec:110(11):1820-36. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11576.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23217128]

Porpiglia F,Tarabuzzi R,Cossu M,Vacca F,Terrone C,Fiori C,Scarpa RM, Is laparoscopic bladder diverticulectomy after transurethral resection of the prostate safe and effective? Comparison with open surgery. Journal of endourology. 2004 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 15006059]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMagera JS Jr, Adam Childs M, Frank I. Robot-assisted laparoscopic transvesical diverticulectomy and simple prostatectomy. Journal of robotic surgery. 2008 Sep:2(3):205-8. doi: 10.1007/s11701-008-0100-z. Epub 2008 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 27628263]

Cermak S, Putman S. [Micturition Complaints in Men: One Symptom, Multiple Causes]. Praxis. 2018:107(11):593-598. doi: 10.1024/1661-8157/a002974. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29788851]

Boström PJ, Kössi J, Laato M, Nurmi M. Risk factors for mortality and morbidity related to radical cystectomy. BJU international. 2009 Jan:103(2):191-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07889.x. Epub 2008 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 18671789]

Lawrentschuk N, Colombo R, Hakenberg OW, Lerner SP, Månsson W, Sagalowsky A, Wirth MP. Prevention and management of complications following radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. European urology. 2010 Jun:57(6):983-1001. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.02.024. Epub 2010 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 20227172]

Sullivan JW, Grabstald H, Whitmore WF Jr. Complications of ureteroileal conduit with radical cystectomy: review of 336 cases. The Journal of urology. 1980 Dec:124(6):797-801 [PubMed PMID: 7441828]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePowell CR, Kreder KJ. Treatment of bladder diverticula, impaired detrusor contractility, and low bladder compliance. The Urologic clinics of North America. 2009 Nov:36(4):511-25, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2009.08.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19942049]

Mićić S, Ilić V. Incidence of neoplasm in vesical diverticula. The Journal of urology. 1983 Apr:129(4):734-5 [PubMed PMID: 6405057]

Golijanin D, Yossepowitch O, Beck SD, Sogani P, Dalbagni G. Carcinoma in a bladder diverticulum: presentation and treatment outcome. The Journal of urology. 2003 Nov:170(5):1761-4 [PubMed PMID: 14532771]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence