Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Hand Radiocarpal Joint

Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Hand Radiocarpal Joint

Introduction

The wrist is a joint complex comprised of three other joints: the radiocarpal joint, the ulnocarpal joint, and the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ). The radiocarpal joint is a synovial joint formed by the articulation between the distal radius and the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum as well as the soft tissue structures that hold the joint together.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The osseous structures of the radiocarpal joint include the distal radius, the scaphoid, the lunate, and the triquetrum.

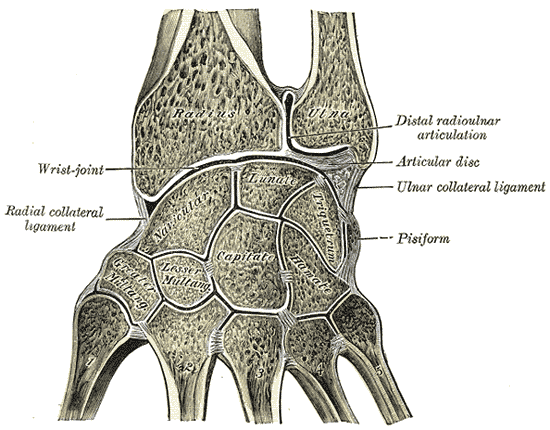

The distal radius has two concaved surfaces involved in the radiocarpal joint, the scaphoid fossa and the lunate fossa. These concavities provide a surface for direct articulation between the radius and the two carpal bones.[1] The articulation of the distal radius with the triquetrum is indirect and facilitated via a biconcave fibrocartilage expansion called the triangular fibrocartilage (TFC) disc proper.[2] The combination of the concaved fossae and the biconcave TFC allows for fluid articulation with the convex surfaces of the scaphoid and lunate and triquetrum. While most bones in the body require muscle contraction for motion, the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum form an intercalated segment, and are purely dependent on surrounding mechanical forces for motion due to the fact they have no tendinous insertions.[3]

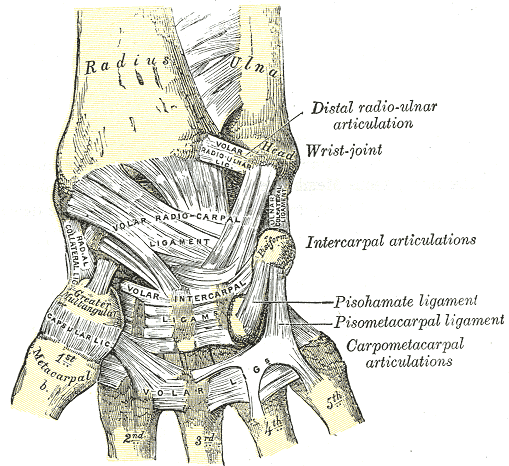

The soft tissue structures of the wrist are mainly comprised of the triangular fibrocartilage complex and the intrinsic and extrinsic ligaments. The ligaments of importance regarding the radiocarpal joint are the extrinsic ligaments which serve as a connection between the distal radius and the carpal bones.[3] The extrinsic ligaments of concern are the dorsal radiocarpal ligament, the short radiolunate ligament, the long radiolunate ligament, the radioscaphocapitate ligament, and the radioscapholunate ligament.

The dorsal radiocarpal ligament originates on the dorsal surface of the radius spreads medially distally until it inserts on the lunate and triquetrum.[3][4] The role of this ligament is to provide dorsal stabilization to the scaphoid throughout all wrist movements.[4]

The short and long radiolunate ligaments are volar ligaments that originate on the ulnar aspect of the radius and insert onto the lunate. The role of the long radiolunate is to limit the motion of the lunate distally and medially (towards the ulna).[3]

The radioscaphocapitate ligament is another volar structure that originates at the radial styloid and inserts on the scaphoid and proximal capitate. Of importance, is the fact that it runs in parallel with the long radiolunate ligament which forms a space. This space is an area of weakness that can predispose to carpal instability known as the space of Poirier.[3][5]

Lastly is the radioscapholunate ligament, also known as the ligament of Testut. This structure is technically not a ligament since it provides no structural support.[3] However, it does serve as a conduit for vasculature to the lunate. Disruption may lead to avascular necrosis of the proximal lunate known as Kienböck's disease.[6]

A two-layered capsule covers the articulation of the above osseous and soft tissue structures. The outer portion of the capsule is composed of fibrous connective tissue which provides added structural support to the joint complex. The inner layer is a synovial membrane responsible for the secretion of synovial fluid to keep the joint lubricated.[7] When all of the components are functioning in unison with the distal radioulnar joint and the ulnocarpal joint, a condyloid or ellipsoid joint is formed allowing for varying degrees of flexion, extension, radial deviation, and ulnar deviation.[8]

The radiocarpal joint also serves as the primary site for dispersion of force traveling through the wrist. Studies demonstrate that when the wrist is held in a neutral position the radiocarpal joint experiences 80% of the force that travels across the joint compared to the 20% experienced by the ulnocarpal joint.[8]

The radiocarpal joint allows proper hand movements, this includes flexion, extension, adduction, and abduction of the wrist but the supination and pronation of the hand, movements known as rotation, cannot be done by the hand as a unit or independent in relation to the forearm. Hand rotation is possible because the forearm needs to rotate too[9], it means supination/pronation of the hand is performed in concert with supination/rotation of the forearm.

Embryology

The first signs of radiocarpal development present in the outpouching of lateral plate mesoderm resulting in the formation of the upper limb bud during the fourth week of embryogenesis.[10] The limb bud has a predesignated field of development that is encoded by the Hox gene, a transcription factor crucial in segmental embryologic development.[11] The development of the limb bud progresses in a proximal-distal pattern defined by three segments. The humerus is the byproduct of the most proximal segment, the radius and ulna arise from the intermediate segment, and the carpal bones, metacarpals, and phalanges arise from the distal segment.[10] During the eighth week of fetal development, the four bones of the radiocarpal joint (radius, scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum) have undergone some amount of chondrogenesis.[12] As with the other bones of the wrist and hand, ossification will continue throughout fetal development and into the early years of life.

The palmar radiocarpal ligament, a key instrument in joint stability, appears during week eight, preceding the dorsal radiocarpal ligament which appears during week ten.[12] Along with the ligaments of the radiocarpal joint, the formation of the triangular fibrocartilage disc is significant due to its articulation with radius and triquetrum which do not come in direct contact with one another. The triangular fibrocartilage disc is present by the end of week eight but is not well defined until week 14.[12] Encompassing the entire joint surface, including the ligaments and fibrocartilaginous structures, is the articular capsule that can be clearly defined by week eleven. The synovial membrane, the inner portion of the joint capsule develops later, and its intricate structure is identifiable by week 13.[12]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

One of the most commonly palpated arteries in clinical medicine is the radial artery. This artery runs deep to the majority of the musculature in the forearm, before becoming more superficial as it courses across the radius entering the hand. At the site where it is commonly palpated, the radial artery sits between the skin and the pronator quadratus.

The distal radius receives blood from the radial, anterior interosseous, posterior interosseous, and ulnar artery. The anterior interosseous does the majority of the work as it branches into periosteal and cortical branches at the distal radial metaphysis.[13]

The scaphoid receives a palmar and dorsal blood supply. The palmar surface receives vascular supply by the palmar carpal artery and the superficial palmar artery, while the dorsal surface gets its blood provided by the dorsal scaphoid artery, the dorsal carpal artery, and the styloid artery.[14] The dorsal carpal artery is also important in that it supplies the proximal scaphoid via retrograde blood flow.

The lunate has a variable blood supply that utilizes branches of the dorsal intercarpal arterial arch and the dorsal radiocarpal arch. The palmar surface of the lunate is supplied by nutrient vessels that traverse the various ligaments that insert on the lunate.[6] The triquetrum like the lunate receives a majority of its blood supply from the nutrient vessels that run within the vast network of ligaments in the wrist.

The lymphatics of the radiocarpal joint follow a similar course as the vasculature. These lymphatics divide into a deep and superficial group and further subclassified based on their location of radial or ulnar.

Nerves

The radiocarpal joint has the ability to flex, extend, and deviate both radially and ulnarly. The musculature that allows for radiocarpal extension receives innervation from the radial nerve and its motor branches, the deep branch of the radial nerve, and the posterior interosseous nerve.

The innervation of the muscles responsible for wrist flexion is via a combination of the ulnar nerve, the median nerve, and the anterior interosseous nerve (a branch of the median nerve).

The radiocarpal joint also serves as a portion of the floor of the carpal tunnel which the median nerve travels through as it continues distally to provide sensory and motor innervation to the hand.

Cutaneous innervation of the skin overlying the radiocarpal joint originates from multiple sources. The lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve provides innervation to the proximal area of cutaneous sensory innervation on the volar and dorsal surface. The distal dorsal surface is innervated by the superficial branch of the radial nerve, and volar distal region receives nerve supply from the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve.

Muscles

Although a majority of the tendinous extensions of the forearm musculature traverse the radiocarpal joint, only three muscles insert or originate on the bony surface of this joint. The pronator quadratus and the brachioradialis have a fascial connection and share a common insertion on the distal radius.[15] The brachioradialis, which inserts on the distal radius and radial styloid, serves to flex the elbow, supinate the forearm, and pronate the forearm. It receives motor innervation from the radial nerve. The pronator quadratus, innervated by the anterior interosseous nerve, inserts along the volar surface of the distal radius. It is capable of forearm pronation and is a crucial stabilizer of the distal radioulnar joint.

The scaphoid is the one bone of the radiocarpal joint that serves as a site of origin for the musculature of the forearm and hand. The abductor pollicis brevis, which causes abduction about the first metacarpophalangeal joint originates from the scaphoid tubercle and the trapezium and inserts at the base of the proximal phalanx of the first digit.

The majority of the muscles of both the flexor and extensor compartments of the forearm cross a portion of the radiocarpal joint and affect the motion and stability of the joint. Some of the osteology of the radiocarpal joint have a profound effect on the function of those muscles. For example, Lister’s tubercle (bony prominence on the dorsal surface of the distal radius), acts as a pulley for the tendon of the extensor pollicis longus.[16] Without this pulley formed by Lister’s tubercle and the EPL tendon, EPL contraction would lead to abduction.

Physiologic Variants

Research has revealed a variable morphology of the radial and ulnar peaks of Lister’s tubercle. In the most common variant, the radial peak is larger than the ulnar peak. The second most common variant has radial and ulnar peaks that are similar heights. The least common variant has an ulnar peak larger than the radial peak. In the least common variance, or type 3 variance, the tendon of the extensor pollicis longus courses on the radial aspect of the tubercle.[16] In the more common variants, the tendon runs within the peaks or on the ulnar aspect of the tubercle. These differences potentially have clinical implications regarding surgical planning and predisposition to wrist pathologies.

The vascular supply of the lunate is a physiologic variant of concern due to the lunate's association with avascular necrosis, known as Kienböck disease. The arterial vessels of the volar surface are the main vascular supply of the lunate. Commonly, there are two to four vessels that traverse the volar carpal ligaments that nourish the lunate. However, there can uncommonly be only one vessel that supplies the volar surface of the lunate.[17]

Surgical Considerations

A fracture of the distal radius among the most common fractures that present to the emergency department or a primary care office in the United States.[18] It is extremely common in the elderly population usually due to a fall onto an outstretched hand. Osteoporotic change to the metaphysis and epiphysis of the distal radius plays a significant role in the frequency of fracture. One study found that the decrease in bone density in the distal radius had a statistically significant correlation to the densities of the hip and vertebra, which are commonly used to evaluate for osteoporosis.[19] The basis for the classification of distal radius fractures is upon fracture pattern and angulation/displacement of the distal fragment.

- Colles fracture: fracture of the distal radius resulting in dorsal angulation

- Chauffeur fracture: avulsion fracture of the radial styloid

- Smith fracture: fracture of the distal radius that leads to increased volar angulation or volar displacement

- Barton fracture: fracture of the distal radius leading to the displacement of the distal fragment and the carpus, resulting in a fracture-subluxation of the wrist.

All of these fractures are treatable surgically. Commonly a volar approach is utilized to reduce a distal radius fracture. After skin incision and dissection through subcutaneous tissue, the interval between the flexor carpi radialis tendon subsheath and the radial artery is opened revealing the pronator quadratus. The pronator quadratus is elevated off of the fracture site, and a volar plate is applied to provide structural fixation to the reduced fracture.[20]

The scaphoid is the most commonly fractured carpal bone, and like distal radius fractures, it is commonly the consequence of a fall onto an outstretched hand. Nonunion is a common complication in this injury due to the delicate vasculature of the scaphoid. However, not all fractures of the scaphoid require surgical attention. Indications for surgical management in a scaphoid fracture include displacement, fracture of the proximal pole, and nonunion.[21] There are multiple surgical approaches for scaphoid fixation, but minimally invasive percutaneous techniques are among the most popular. Kirschner wires are percutaneously driven through the fracture, and a cannulated screw is directed down the wire to provide fixation to the scaphoid.[21]

Falls onto outstretched hands do not only cause damage to osseous structures of the radiocarpal joint, but it can also cause damage to ligamentous structures. The scapholunate interosseous ligament plays a crucial role in wrist stability and injury to this structure can be challenging to diagnose. Patients typically complain of pain and wrist popping or clicking with wrist extension and grip.[22] Instability may be appreciable on radiography displaying the scaphoid in a relative position of palmar flexion and the lunate in a relative position of dorsiflexion.[22] Based on radiographic measurements a diagnosis of dorsal intercalated segmental instability can be made, which requires attention due to the possibility of it advancing to scapholunate advanced collapse (SLAC). SLAC leads to inappropriate dispersion of force across the wrist which can result in accelerated progression of wrist arthritis. Arthroscopy is utilized to provide the surgeon with information on the extent of structural damage so that they may take appropriate surgical steps.

Clinical Significance

Avascular necrosis of the lunate, also known as Kienböck disease is a condition that occurs due to the disruption of the vasculature to the lunate. While there is no definitive underlying cause for this condition, it is well known what can result if the condition progresses. The collapse of the lunate will lead to proximal migration of the capitate. This altered alignment will result in abnormal scaphoid motion and ultimately arthrosis throughout the radiocarpal joint.[23] However, not all patients who develop Kienböck will progress to widespread wrist dysfunction and osteoarthritis. In the early stages, this condition can be managed conservatively with NSAIDs and rest. Radiographic evidence showing advanced disease requires surgical management ranging from bone graft to wrist fusion.

Buckle fractures are typically found in pediatric patients after a fall onto an outstretched hand. Radiographically it is represented by compression and bulging of the cortex at the distal radius.[24] Children typically have softer more flexible bone compared to adults, explaining why this injury pattern is more common in children. Because this fracture does not typically present with displacement or overt irregularity management is usually non-surgical. Patients are placed in either a short arm cast or a removable splint and are encouraged to avoid activities that could lead to reinjury.[24]

Arthritis is an inflammatory disease of a joint that can be caused by a degenerative change (osteoarthritis) or autoimmune degeneration (rheumatoid arthritis). Degenerative changes in osteoarthritis are the result of repetitive impaction of the wrist leading to the destruction of articular cartilage. This process can be hastened by conditions that alter the dispersion of forces traveling across the wrist. Rheumatoid arthritis is a condition where the body produces an abundance of immune cells and cytokines that target the body's articular cartilage. Both forms of arthritis present with pain in the joints and impaired range of motion. However, osteoarthritis tends to worsen with the increased use of the joint, while rheumatoid arthritis loosens up with increased use. Additionally, joints affected with rheumatoid arthritis will be warm and swollen. Just as the presentations of these conditions are different, so are their treatments. Osteoarthritis is managed primarily with NSAIDs, rest and if severe enough intra-articular corticosteroid injections. Rheumatoid arthritis has an underlying autoimmune cause. Therefore, treatment aims to reduce the immune response. Pharmacologic agents such as methotrexate are first-line treatment options for this condition. If methotrexate is unable to keep the diseases from progressing biologic agents are an alternative.

Other Issues

Chronic pain of the wrist can range from posttraumatic to degenerative causes for which the non-operative treatments are preferred, but when despite this approach the pain becomes disabling and the function of the wrist is compromised or deteriorated a surgical managed could be considered. Some surgical options include arthroscopic wrist procedures, arthrodesis, denervation. Arthrodesis, which is a fusion of two adjacent bones to immobilize a joint, and resection are considered salvage procedures [25].

An alternative to those salvage procedures is wrist denervation, its concept is not new but the application of this technique has had several modifications and this looks like a promising procedure for palliative care [26]. However, we have to keep in mind that it doesn't improve further degeneration of the joint, and therefore underlying arthritis. More studies are needed to asses the duration of the relief.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Wrist Ligaments, Anterior View of Radius, Ulna, Distal radio-ulnar articulation, Wrist joint, Volar radioulnar ligament, Volar radiocarpal ligament, Metacarpal, Intercarpal articulations, Pisohamate ligament, pisometacarpal ligament, carpometacarpal articulations, Volar, Greater Trapezium, Capsular ligament, Radial Collateral ligament, Pisiform,

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Obert L, Loisel F, Gasse N, Lepage D. Distal radius anatomy applied to the treatment of wrist fractures by plate: a review of recent literature. SICOT-J. 2015 Jun 19:1():14. doi: 10.1051/sicotj/2015012. Epub 2015 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 27163070]

Bae WC, Ruangchaijatuporn T, Chang EY, Biswas R, Du J, Statum S, Chung CB. MR morphology of triangular fibrocartilage complex: correlation with quantitative MR and biomechanical properties. Skeletal radiology. 2016 Apr:45(4):447-54. doi: 10.1007/s00256-015-2309-z. Epub 2015 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 26691643]

Kijima Y, Viegas SF. Wrist anatomy and biomechanics. The Journal of hand surgery. 2009 Oct:34(8):1555-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.07.019. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19801111]

Viegas SF, Yamaguchi S, Boyd NL, Patterson RM. The dorsal ligaments of the wrist: anatomy, mechanical properties, and function. The Journal of hand surgery. 1999 May:24(3):456-68 [PubMed PMID: 10357522]

Trail IA, Stanley JK, Hayton MJ. Twenty questions on carpal instability. The Journal of hand surgery, European volume. 2007 Jun:32(3):240-55 [PubMed PMID: 17418465]

Lamas C, Carrera A, Proubasta I, Llusà M, Majó J, Mir X. The anatomy and vascularity of the lunate: considerations applied to Kienböck's disease. Chirurgie de la main. 2007 Feb:26(1):13-20 [PubMed PMID: 17418764]

Ralphs JR, Benjamin M. The joint capsule: structure, composition, ageing and disease. Journal of anatomy. 1994 Jun:184 ( Pt 3)(Pt 3):503-9 [PubMed PMID: 7928639]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBerger RA. The anatomy and basic biomechanics of the wrist joint. Journal of hand therapy : official journal of the American Society of Hand Therapists. 1996 Apr-Jun:9(2):84-93 [PubMed PMID: 8784671]

Soubeyrand M, Assabah B, Bégin M, Laemmel E, Dos Santos A, Crézé M. Pronation and supination of the hand: Anatomy and biomechanics. Hand surgery & rehabilitation. 2017 Feb:36(1):2-11. doi: 10.1016/j.hansur.2016.09.012. Epub 2016 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 28137437]

Al-Qattan MM, Kozin SH. Update on embryology of the upper limb. The Journal of hand surgery. 2013 Sep:38(9):1835-44. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.03.018. Epub 2013 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 23684522]

Burke AC, Nelson CE, Morgan BA, Tabin C. Hox genes and the evolution of vertebrate axial morphology. Development (Cambridge, England). 1995 Feb:121(2):333-46 [PubMed PMID: 7768176]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHita-Contreras F, Martínez-Amat A, Ortiz R, Caba O, Alvarez P, Prados JC, Lomas-Vega R, Aránega A, Sánchez-Montesinos I, Mérida-Velasco JA. Development and morphogenesis of human wrist joint during embryonic and early fetal period. Journal of anatomy. 2012 Jun:220(6):580-90. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01496.x. Epub 2012 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 22428933]

Lamas C, Llusà M, Méndez A, Proubasta I, Carrera A, Forcada P. Intraosseous vascularity of the distal radius: anatomy and clinical implications in distal radius fractures. Hand (New York, N.Y.). 2009 Dec:4(4):418-23. doi: 10.1007/s11552-009-9204-9. Epub 2009 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 19475457]

Oehmke MJ, Podranski T, Klaus R, Knolle E, Weindel S, Rein S, Oehmke HJ. The blood supply of the scaphoid bone. The Journal of hand surgery, European volume. 2009 Jun:34(3):351-7. doi: 10.1177/1753193408100117. Epub 2009 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 19282403]

Hohendorff B, Knappwerth C, Franke J, Müller LP, Ries C. Pronator quadratus repair with a part of the brachioradialis muscle insertion in volar plate fixation of distal radius fractures: a prospective randomised trial. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2018 Oct:138(10):1479-1485. doi: 10.1007/s00402-018-2999-5. Epub 2018 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 30062458]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChan WY, Chong LR. Anatomical Variants of Lister's Tubercle: A New Morphological Classification Based on Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Korean journal of radiology. 2017 Nov-Dec:18(6):957-963. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2017.18.6.957. Epub 2017 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 29089828]

DURBIN FC. The early changes of Kienböck's disease of the carpal lunate bone. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1951 Jun:44(6):482-8 [PubMed PMID: 14864534]

MacIntyre NJ, Dewan N. Epidemiology of distal radius fractures and factors predicting risk and prognosis. Journal of hand therapy : official journal of the American Society of Hand Therapists. 2016 Apr-Jun:29(2):136-45. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2016.03.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27264899]

Amiri L, Kheiltash A, Movassaghi S, Moghaddassi M, Seddigh L. Comparison of Bone Density of Distal Radius With Hip and Spine Using DXA. Acta medica Iranica. 2017 Feb:55(2):92-96 [PubMed PMID: 28282704]

Alluri RK, Hill JR, Ghiassi A. Distal Radius Fractures: Approaches, Indications, and Techniques. The Journal of hand surgery. 2016 Aug:41(8):845-54. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2016.05.015. Epub 2016 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 27342171]

Ko JH, Pet MA, Khouri JS, Hammert WC. Management of Scaphoid Fractures. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2017 Aug:140(2):333e-346e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003558. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28746289]

White NJ, Rollick NC. Injuries of the Scapholunate Interosseous Ligament: An Update. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2015 Nov:23(11):691-703. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00254. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26498586]

van Leeuwen WF, Tarabochia MA, Schuurman AH, Chen N, Ring D. Risk Factors of Lunate Collapse in Kienböck Disease. The Journal of hand surgery. 2017 Nov:42(11):883-888.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.06.107. Epub 2017 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 28888572]

Ben-Yakov M, Boutis K. Buckle fractures of the distal radius in children. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2016 Apr 19:188(7):527. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.151239. Epub 2016 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 26976961]

Wu CH, Strauch RJ. Wrist Denervation: Techniques and Outcomes. The Orthopedic clinics of North America. 2019 Jul:50(3):345-356. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2019.03.002. Epub 2019 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 31084837]

Milone MT, Klifto CS, Catalano LW 3rd. Partial Wrist Denervation: The Evidence Behind a Small Fix for Big Problems. The Journal of hand surgery. 2018 Mar:43(3):272-277. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.12.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29502579]