Introduction

An anal fissure is a superficial tear in the skin distal to the dentate line and is a cause of frequent emergency department visits. In most cases, anal fissures are a result of hard stools or constipation, or injury. Anal fissures are common in both adults and children, and those with a history of constipation tend to have more frequent episodes of this condition. Anal fissures can be acute (lasting less than 6 weeks) or chronic (more than 6 weeks). The majority of anal fissures are considered primary and typically occur at the posterior midline. See Image. Chronic Posterior Anal Fissure. A small percentage of these may occur at the anterior midline. Other locations (atypical/secondary fissures) can be caused by other underlying conditions that require further workup. The diagnosis of an anal fissure is primarily clinical. Several treatment options exist, including medical management and surgical options.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Causes of anal fissures commonly include constipation, chronic diarrhea, sexually transmitted diseases, tuberculosis, inflammatory bowel disease, HIV, anal cancer, childbearing, prior anal surgery, and anal sexual intercourse. The majority of acute anal fissures are thought to be due to the passage of hard stools, sexually transmitted infection, or anal injury due to penetration. A chronic anal fissure typically is a recurrence of an acute anal fissure. It is thought to be also caused by the passage of hard stools against an elevated anal sphincter tone pressure, with symptoms lasting greater than 6 weeks. Underlying conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, tuberculosis, HIV, anal cancer, and prior anal surgery are predisposing factors to both acute and chronic atypical anal fissures. Approximately 40% of patients who present with acute anal fissures progress to chronic anal fissures.[4][5]

Epidemiology

Anal fissures are present in any age group; however, they are mostly identified in the pediatric and middle-aged populations. Gender is equally affected, and approximately 250,000 new cases are diagnosed each year in the United States.[6]

Pathophysiology

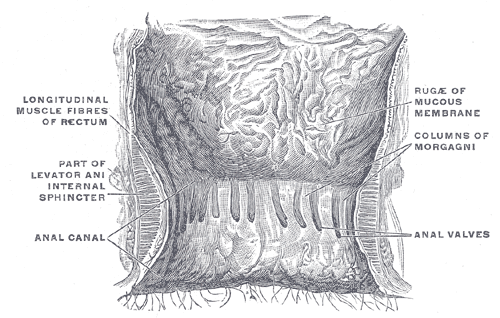

The anoderm refers to the epithelial component of the anal canal (see Image. The Large Intestine). The location is inferior to the dentate line. It is a very sensitive area to microtrauma and can tear with repetitive trauma or increased pressure. The high pressures in this area can result in delayed healing secondary to ischemia. The tear can sometimes be deep enough to expose the sphincter muscle. Together with spasms of the sphincter, this creates severe pain with bowel movements, as well as some rectal bleeding. It is well known that the most common location of an anal fissure is the posterior midline because this location receives less than half of perfusion compared to the rest of the anal canal. The perfusion of the anal canal has an inverse relationship to sphincter pressure. Other locations of anal fissures, such as lateral fissure, are indicative of an underlying etiology (HIV, tuberculosis, Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, among others). The cause of this other location is not well known. Anterior fissures are rare and are associated with external sphincter injury and dysfunction.

History and Physical

Patients with acute anal fissures present with complaints of anal pain that is worse during defecation. At times, there is associated bleeding with bowel movements, but usually not frank hemorrhage. The pain usually persists for hours after defecation. Often, acute anal fissures may be misdiagnosed as external or internal hemorrhoids. Therefore, a thorough physical exam should delineate between the 2. Patients with chronic anal fissures have a history of painful defecation with or without rectal bleeding that has been ongoing for several months to possibly years. Associated constipation is the most common factor involving chronic anal fissures, and patients provide a longstanding history of hard stools. Patients with underlying granulomatous diseases such as Crohn disease, among others, sometimes provide a history of chronic anal pain during defecation that is intermittent rather than constant over an extended period.

The physical exam of the patient with an anal fissure should involve the most comfortable position for the patient. Literature suggests the best position is the prone jackknife position, where the patient lies prone, and the bed is folded so that the patient is flexed at the hips. The bed typically used to achieve this position is usually in an operating or procedure room. Therefore, the best way to achieve this position in the acute care or office would be to have the patient bend over the exam table. However, an adequate physical exam can often be achieved by having the patient in a lateral decubitus position. It is imperative that physical manipulation of the anus or rectum via digital exam should be kept to a minimum, and instrumentation such as anoscopy should never be used. An anal fissure appears as a superficial laceration in the acute presentation, usually longitudinal, extending proximally. Bleeding may or may not be present. The fissure and sometimes the entire anal sphincter may be extremely tender to palpation. In thin patients, this laceration is usually easily identified; however, in obese patients, it may not be as identifiable. In an obese patient, gently pressing on the anterior or posterior anal sphincter may reproduce the pain, and a diagnosis can be made. In chronic anal fissures, there may be a tear large and deep enough to expose the muscular fibers of the anal sphincter. Also, due to the repeated injury and healing cycle, the edges sometimes appear raised, and a thickening of tissue at the distal ends of the tears may be present, called a sentinel pile. Granulation tissue may or may not be present, depending on the chronicity and the stage of healing.

Evaluation

If the patient has chronic recurrent anal fissures, an examination under anesthesia is recommended to help diagnose the exact cause and sometimes treat the patient. Evaluation of both acute and chronic anal fissures initially involves determining if it is a primary or secondary anal fissure. As described earlier, a primary or typical anal fissure occurs in the posterior or anterior midline, and an atypical or secondary anal fissure occurs in any location other than a primary anal fissure. If an atypical or secondary anal fissure is encountered, conditions such as Crohn disease should be immediately ruled out. It is worth noting that patients with Crohn or other underlying conditions can have anal fissures located at the typical/primary locations.

Treatment / Management

The initial treatment of anal fissures is with medical interventions. Frequent sitz baths, analgesics, stool softeners, and a high-fiber diet are recommended. Prevention of recurrence is the primary goal. Adequate fluid intake is also helpful in preventing the recurrence of anal fissures and is strongly encouraged. Suppose conservative management with dietary changes and laxatives fails. Other options can be used in that case, including topical analgesics such as 2% lidocaine jelly, topical nifedipine, topical nitroglycerin, or a combination of topical nifedipine and lidocaine compounded by another medication. Topical nifedipine works by reducing anal sphincter tone, which promotes blood flow and faster healing. Topical nitroglycerin acts as a vasodilator to encourage increased blood flow to the fissure area, increasing the healing rate. While both are effective treatments, topical nifedipine is superior to topical nitroglycerin in 2 ways. First, nifedipine has been found to result in a higher healing rate compared to nitroglycerin. Second, it resulted in fewer side effects, as nitroglycerin frequently causes headaches and hypotension. If patients use nitroglycerin, it is recommended that they apply the ointment in a seated position and refrain from standing too quickly. Patients should also avoid medications such as sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil while using nitroglycerin.[7][8][9](A1)

Chronic anal fissure (CAF) is typically more difficult to treat, given recurrence and complications. Aside from using nitrates and calcium channel blockers, a third pharmacological method can be employed to prevent a recurrence of CAF. Botulinum toxin is considered safe and provides significant pain relief. Botulinum toxin is superior and the most effective than nitrates and calcium channel blockers. Conservative methods are likely to fail and have a higher failure rate with chronically recurring anal fissures. In these situations, the gold standard is the lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS). This surgical procedure treats CAF by preventing hypertonia of the internal sphincter. In a study conducted between 1984 and 1996, 96% of patients undergoing LIS had complete resolution of their CAF within 3 weeks. An open and closed technique can be used under local or general anesthesia. It has been found that those undergoing LIS with local anesthesia have a higher rate of recurrence of CAF. In the open technique of LIS, an incision is made across the intersphincteric groove. Blunt dissection is then employed to separate the internal sphincter from the anal mucosa. Finally, the internal sphincter is divided with scissors. In the closed technique of LIS, a small incision is made at the intersphincteric groove, and a scalpel is inserted parallel to the internal sphincter. The scalpel is advanced along the intersphincteric groove, and the internal sphincter is then divided by rotating the scalpel toward it. The healing rate is the same with either an open or closed approach.

Although LIS is nearly curative in all CAF cases, it comes with complications that the healthcare provider should discuss with the patient before the procedure. Fecal incontinence (including uncontrolled flatus, mild stool, soiling, and gross incontinence) is the major complication; it occurs in approximately 45% of patients in the immediate postoperative period, with a higher likelihood in females (50% versus 30% in males.) Despite the high rate of incontinence, it is transient and usually resolves. Within 5 years of LIS, the incontinence rate is substantially reduced to less than 10%, with a gross loss of solid stool being less than 1%. The recurrence of CAF in post-LIS patients is approximately 5%, and conservative methods with pharmacological treatment cure approximately 75%. Other acute complications from LIS surgery include excessive bleeding, encountered more commonly during the open technique, and may require suture ligation. Approximately 1% of patients undergoing the closed technique develop a perianal abscess, primarily because of the dead space created by the separation of the anal mucosa. One long-term complication of sphincterotomy encountered more frequently in the repair of posterior CAFs is a keyhole deformity. A keyhole deformity is usually asymptomatic and is well tolerated by patients. In a study of over 600 patients undergoing internal sphincterotomy, only 15 developed a keyhole deformity, which was not associated with any anal incontinence, but went on to receive the repair.

Differential Diagnosis

An anal fissure is a clinical diagnosis made essentially by physical exam alone, which must be done to rule out other possible causes of rectal pain. Hemorrhoids are the most common finding in patients with rectal pain. However, only external hemorrhoids are painful, especially if they are thrombosed. Patients can also have perianal abscesses that cause pain on defecation and can bleed. Perianal abscesses can also form anal fistulas to a deeper site and either bleed or have purulent drainage. Patients with sexually transmitted infections, inflammatory bowel disease, or tuberculosis can form perianal ulcerations. A rare condition known as solitary rectal ulcer syndrome can also be encountered; however, this lesion has no known cause and is usually found by sigmoidoscopy, several centimeters proximal to the anus itself.

Prognosis

Acute anal fissures in low-risk patients typically do well with conservative management and resolve within a few days to a few weeks. However, some of these patients develop CAF, which requires pharmacological treatment or surgical management. Over 90% of patients undergoing surgical management achieve a cure within 3 to 4 weeks postoperatively.[10]

Complications

The complications of anal fissures include bleeding, pain, infection, incontinence, and fistula formation, which is the most serious complication of anal fissures.

Consultations

Clinical guidelines on anal fissure management:

- Acute anal fissure: Non-operative treatment that includes high fiber diet, stool softeners, and sitz baths

- Chronic anal fissure: Topical agents like nitrates or calcium channel blockers

- Chronic anal fissure: Those who fail to respond to pharmacological therapy may be treated with botulinum toxin or internal anal sphincterotomy.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with anal fissures should be educated on the importance of following a high-fiber diet, using stool softeners, and avoiding constipation

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team best manages anal fissures. Anal fissures are common presentations in the emergency department, urgent care, or the primary care provider. Even though benign, these lesions can cause significant pain and affect the quality of life. Because of the high number of patients with anal fissures, a surgeon can't see them all; hence, based on current guidelines, acute cases are usually managed by the primary care provider with lifestyle changes, laxatives, and diet. The pharmacist and primary care provider must educate the patient on avoiding constipation; this not only leads to a decreased incidence of anal fissures but helps reduce the cost of managing the anal fissure. A dietary consult with a nurse educator or dietician is highly recommended, as patients need to know which foods they should eat to avoid constipation. Often nurses and pharmacists help patients with anal fissures and can provide education about medication used to relieve pain and how to perform sitz baths. The nurse and pharmacist should help the interprofessional team provide a solution if there are untoward consequences or increased pain. Patients who fail to respond to conservative measures should be referred to a specialist. The condition can be treated in many ways; however, when medical treatments fail, it is essential to refer the patient to a colorectal surgeon who has more experience with this disorder than most other healthcare providers.

Outcomes

The prognosis for most patients is good as long as they change their lifestyle and diet. For recalcitrant cases, surgery may be an option. However, these lesions recur in 4-6% of patients, even after surgical treatment.[11][12][13]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Large Intestine. The interior of the anal cami and lower part of the rectum shows the columns of Morgagni and the anal valves between their lower ends.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Salem AE, Mohamed EA, Elghadban HM, Abdelghani GM. Potential combination topical therapy of anal fissure: development, evaluation, and clinical study†. Drug delivery. 2018 Nov:25(1):1672-1682. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2018.1507059. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30430875]

Siddiqui J, Fowler GE, Zahid A, Brown K, Young CJ. Treatment of anal fissure: a survey of surgical practice in Australia and New Zealand. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2019 Feb:21(2):226-233. doi: 10.1111/codi.14466. Epub 2018 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 30411476]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCarter D, Dickman R. The Role of Botox in Colorectal Disorders. Current treatment options in gastroenterology. 2018 Dec:16(4):541-547. doi: 10.1007/s11938-018-0205-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30397849]

Choi YS, Kim DS, Lee DH, Lee JB, Lee EJ, Lee SD, Song KH, Jung HJ. Clinical Characteristics and Incidence of Perianal Diseases in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Annals of coloproctology. 2018 Jun:34(3):138-143. doi: 10.3393/ac.2017.06.08. Epub 2018 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 29991202]

Jamshidi R. Anorectal Complaints: Hemorrhoids, Fissures, Abscesses, Fistulae. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2018 Mar:31(2):117-120. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1609026. Epub 2018 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 29487494]

Ebinger SM, Hardt J, Warschkow R, Schmied BM, Herold A, Post S, Marti L. Operative and medical treatment of chronic anal fissures-a review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of gastroenterology. 2017 Jun:52(6):663-676. doi: 10.1007/s00535-017-1335-0. Epub 2017 Apr 10 [PubMed PMID: 28396998]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMahmoud NN, Halwani Y, Montbrun S, Shah PM, Hedrick TL, Rashid F, Schwartz DA, Dalal RL, Kamiński JP, Zaghiyan K, Fleshner PR, Weissler JM, Fischer JP. Current management of perianal Crohn's disease. Current problems in surgery. 2017 May:54(5):262-298. doi: 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2017.02.003. Epub 2017 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 28583256]

Stewart DB Sr, Gaertner W, Glasgow S, Migaly J, Feingold D, Steele SR. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Anal Fissures. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2017 Jan:60(1):7-14 [PubMed PMID: 27926552]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVogel JD, Johnson EK, Morris AM, Paquette IM, Saclarides TJ, Feingold DL, Steele SR. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Anorectal Abscess, Fistula-in-Ano, and Rectovaginal Fistula. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2016 Dec:59(12):1117-1133 [PubMed PMID: 27824697]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBrady JT, Althans AR, Neupane R, Dosokey EMG, Jabir MA, Reynolds HL, Steele SR, Stein SL. Treatment for anal fissure: Is there a safe option? American journal of surgery. 2017 Oct:214(4):623-628. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.06.004. Epub 2017 Jul 5 [PubMed PMID: 28701263]

Sahebally SM, Meshkat B, Walsh SR, Beddy D. Botulinum toxin injection vs topical nitrates for chronic anal fissure: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2018 Jan:20(1):6-15. doi: 10.1111/codi.13969. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29166553]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSalih AM. Chronic anal fissures: Open lateral internal sphincterotomy result; a case series study. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2017 Mar:15():56-58. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2017.02.005. Epub 2017 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 28239456]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLiang J, Church JM. Lateral internal sphincterotomy for surgically recurrent chronic anal fissure. American journal of surgery. 2015 Oct:210(4):715-9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.05.005. Epub 2015 Jun 27 [PubMed PMID: 26231724]