Introduction

The cerebral cortex is composed of a complex association of tightly packed neurons covering the outermost portion of the brain. It is the gray matter of the brain. Lying right under the meninges, the cerebral cortex divides into four lobes: frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital lobes, each with a multitude of functions. It is characteristically known for its bulges of brain tissue known as gyri, alternating with deep fissures known as sulci. The enfolding of the brain is an adaptation to the dramatic growth in brain size during evolution. The various folding of brain tissue allowed large brains to fit in relatively small cranial vaults that had to remain small to accommodate the birth process.[1] Notable sulci include the Sylvian fissure which divides the temporal lobe from the frontal and parietal lobe, the central sulcus which separates the frontal and parietal lobes, the parieto-occipital sulcus which divides the parietal and occipital lobes, and the calcarine sulcus which divides the cuneus from the lingual gyrus.

The cerebral cortex contains sensory, motor and important association areas. The thalamus receives somatosensory information and conveys it to the primary somatosensory cortex in the postcentral gyrus of the parietal lobe. Other important primary cortical sensory areas include the temporal lobe auditory cortex and the occipital lobe visual cortex. Each sensory area has associated sensations given specific stimuli, providing meaning to sensations. The motor regions of the cerebral cortex are located predominantly in the frontal lobe, anterior to the central sulcus, and include the primary motor cortex (found in the precentral gyrus) and the premotor cortex, which initiates and regulates voluntary movement.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Frontal Lobe

The frontal lobe is the largest lobe of the brain, lying in front of the central sulcus. Both anatomically and functionally, it divides into different significant areas. The dorsolateral frontal lobe is divided into three major areas which include the prefrontal cortex, the premotor cortex, and the primary motor cortex. Damage to any of these areas may lead to weakness and impaired execution of motor tasks of the contralateral side. The inferolateral areas of the dominant hemisphere (usually left side) of the frontal lobe are the expressive language area (Broca area, Brodmann areas 44 and 45), to which damage will result in a non-fluent expressive type of aphasia. Other frontal lobe areas including the orbitofrontal area and the medial frontal area are involved in a variety of higher functioning processing, such as regulating emotions, social interactions, and personality. The medial frontal cortex is also the central brain micturition center. The frontal lobes are critical for more difficult decisions and interactions that are essential for human behavior.[2] Thus, damage to this area may result in disinhibition and deficits in concentration, orientation, and judgment. A frontal lobe lesion may also result in regression or a re-emergence of primitive reflexes. The frontal eye fields are the central saccadic eye movement control area, damage to this area may cause eye deviation towards the side of the lesion. However, in patients experiencing a seizure arising from the frontal eye fields will result in the eyes to look away from the lesion.

Temporal Lobe

The temporal lobe processes sensory input into derived meanings for the appropriate retention of emotions, visual memory, and language comprehension. It contains the primary auditory cortex which is involved in processing sound. Wernicke's area is located in the superior temporal gyrus of the dominant hemisphere and manages the comprehension of language. A lesion affecting the superior temporal gyrus will result in receptive aphasia; the person will have fluent speech that makes no sense.[3] The medial temporal lobe consists of important neural structures such as the parahippocampal gyrus, uncus, hippocampus, temporal horn, and choroidal fissure.[4] A lesion in the hippocampus can cause anterograde amnesia and the inability to make new memories. The medial temporal lobe is the primary epileptogenic area of the brain. Seizures originating from these areas not only can affect emotions but can also result in deja-vu or olfactory hallucinations. Bilateral lesions in the amygdala such as in Herpes simplex encephalitis may cause Kluver-Bucy syndrome. In this syndrome, patients would experience dis-inhibited behavior such as hyperphagia, hypersexuality, and hyper-orality. The inferior portion of the optic radiation passes through the temporal lobe. Damage to this part of the white matter tract may cause a superior quadrantic visual field defect commonly called pie in the sky defect. The posteromedial temporal lobes are the "what" visual association areas. Bilateral damage may result in acquired color blindness (achromatopsia).

Parietal Lobe

The parietal lobe is responsible for perception, sensation, and integrating sensory input with the visual system. It houses the primary somatosensory cortex, which is located in the postcentral gyrus, posterior to the central sulcus. It is responsible for receiving contralateral sensory information. Damage to the dominant parietal cortex (usually left) leads to Gerstmann's syndrome. Characteristics of this syndrome include difficulty with writing (agraphia), difficulty with mathematics (acalculia), finger agnosia, and left-right disorientation. Damage to the non-dominant parietal lobe (usually right) leads to agnosia of the contralateral side of the world, also known as hemispatial neglect syndrome. Patients with lesions in the non-dominant parietal lobe exhibit difficulty with self-care such as dressing and washing. Bilateral damage to the "where" visual association areas of the lateral parietal lobe is known as Balint's syndrome, which is characterized by an inability to voluntarily control the gaze (ocular apraxia), inability to integrate components of a visual scene (simultagnosia), and the inability to accurately reach for an object with visual guidance (optic ataxia).[5]

Occipital Lobe

The occipital lobe is the center for the processing of visual input in humans. The primary visual cortex is located in Brodmann Area 17, on the medial side of the occipital lobe within the calcarine sulcus. Damage to a single occipital lobe can result in homonymous hemianopsia as well as visual hallucinations. Bilateral damage to the primary visual cortex can cause blindness (cortical blindness). Clinically it is characterized by loss of sight with preserved light reflexes. Denial of visual loss in cortical blindness is characteristic of Anton syndrome. The patient may also experience visual illusions in which objects would appear larger/smaller than they actually are, or objects appear with abnormal coloration.

Embryology

Human brain development is an intricate process that begins in the 3rd week of gestation. The inception of development involves neural progenitor cells and progresses through one's lifetime. Both molecular events and environmental input are essential in normal brain development, and disruption of either can have drastic effects on neural outcomes. As the brain continues to grow postnatally, 90% of the adult volume will be reached by age six, and the mature brain will be composed of over 100 billion neurons.[1]

By the end of week three, the embryo transforms through a set of processes that are collectively referred to as gastrulation, into a three-layered structure. By the end of the gastrulation process, the neural progenitor cells undergo differentiation and position along the rostral-caudal midline of the embryo. The embryonic region containing the neural progenitor cells is called the neural plate. The notochord is responsible for inducing the overlying ectoderm to differentiate into neuroectoderm and form the neural plate. The neuroepithelia in the neural tube form the CNS neurons, ependymal cells (inner lining of ventricles), oligodendrocytes and astrocytes. The next step in brain development involves the formation of the neural tube. The first sign of neural tube development is the appearance of two ridges that form along the two sides of the neural plate, which gives rise to the neural tube and neural crest cells. Neural crest cells give rise to peripheral nervous system neurons and Schwann cells. The leftover mesoderm differentiates into microglia. The notochord then becomes the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral disk in adult humans.

Also, three primary vesicles add to the regional specification of brain formation. These include the forebrain (prosencephalon), midbrain (mesencephalon) and hindbrain (rhombencephalon). The prosencephalon goes on to first form the telencephalon and then the diencephalon. The telencephalon is responsible for forming the cerebral hemispheres and lateral ventricles. The diencephalon later forms the thalamus, hypothalamus, and 3rd ventricle.

Neurons vary in their size, shape, and function and have a vital role in processing information in the brain. Networks of neurons relay information amongst each other and are responsible for all thoughts, sensations, feelings, and actions. "Since each neuron can make connections with more than 1,000 other neurons, the adult brain is estimated to have more than 60 trillion neuronal connections".[1] The junction between two nerve cells is commonly known as a synapse.

The most prominent brain information processing networks involve the neocortex and the subcortical nuclei, which relay information between the neocortex. The neocortex is a 2–5 mm thick layer of cells that lies on the surface of the brain.[1] The subcortical nuclei are located deep within the brain, underneath the cortex and are thus referred to as sub-cortical nuclei. The subcortical nuclei are groups of neurons that help facilitate communication between the neocortex and body through relay centers transmitting various inputs and outputs. Because both the neocortex and the subcortical nuclei contain the cell bodies of neurons, they are referred to as "gray matter" due to their gray appearance.[1]

Populations of neurons are interconnected via fibers that extend from cell bodies of each individual neuron. Both dendrites and axons represent these "interconnecting fibers". Dendrites are arrays of short branched extensions of nerve cells along which transmit signals from other cells in the body. Their main function is to receive the electrochemical input signals from other neurons. Contrarily, axons are long connecting fibers that extend over long distances and conduct impulses from the cell body to other cells. Axons are responsible for sending electrochemical signals to neurons located in distant locations. Bundles of individual axons form fiber "tracts" in the CNS and "nerves" in the PNS. These resulting tracts and nerves form information processing networks. Injury to axons may result in Wallerian degeneration. Wallerian degenerates denote degeneration of the axon distal to the site of injury as well as a proximal axonal retraction. This allows potential regeneration of the axon if it is located in the PNS.

Axons are wrapped in a fatty substance composed of protein and phospholipids known as myelin. Myelin increases the conduction velocity of signals transmitted down axons through a process known as Saltatory conduction. In between these myelinated regions (internode) are nodal regions (the Nodes of Ranvier) which possess the highest concentration of sodium channels. Myelin forms from oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system (CNS) and by Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Because myelin is white in appearance, fiber pathways of the brain are often referred to as "white matter."

Oligodendrocytes are the most prominent cell type in white matter and are responsible for myelinating axons of neurons in the CNS. Oligodendrocytes are derived from neuroectoderm and have a "fried egg" appearance on histology. Oligodendrocytes are the cells that are injured in multiple sclerosis, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, and leukodystrophies. Each oligodendrocyte can myelinate many axons. Contrast this with Schwann cells which can only myelinate a single axon in the PNS. However, Schwann cells possess the capability to promote axonal regeneration. Schwann cells are injured in Guillan-Barre syndrome.

Ependymal cells are glial cells with a ciliated simple columnar form that line the ventricles and central canal of the spinal cord. Apical surfaces are covered in cilia (which circulate CSF) and microglia (which help in CSF absorption). Microglia are the phagocytic scavenger cells of the CSF and are of mesodermal origin. Microglia are activated in response to tissue damage and fuse to form multinucleated giant cells in HIV-infected individuals.

Astrocytes are the most common glial cell in the CNS and differentiate from neuroectoderm. They provide physical support, repair, extracellular potassium buffer, removal of excess neurotransmitter, component of blood-brain-barrier, and provide a glycogen fuel reserve buffer. Astrocytes activity may be monitored via a GFAP marker.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The brain weighs 2% of total body weight. It receives about 15% of the cardiac output.

Anterior Circulation

The anterior portion of the brain is supplied mainly by branches of the paired internal carotid artery. It accounts for 80% of the blood supply of the brain.

Internal Carotid Arteries (ICA)

The internal carotid artery runs upward through the neck and enters the skull through the carotid canal, located in the petrous portion of the temporal bone just superior to the jugular fossa. The internal carotid branches into the anterior cerebral artery and continues to form the middle cerebral artery. The ICA provides the anterior supply to the circle of Willis.

Anterior Cerebral Arteries (ACA)

The anterior cerebral arteries are branches of the ICA and supply the frontal and superior medial parietal lobes; this includes part of the motor cortex that controls the movement of the contralateral lower limb, the sensory cortex that controls sensation in the contralateral lower limb, Broca's area, and the prefrontal cortex. Both ACAs connect to each other via the anterior communicating artery. Although ACA infarcts are rare due to the collateral circulation provided by the anterior communicating arteries, one would experience contralateral motor and sensory deficits in the lower limbs.

Middle Cerebral Arteries (MCA)

The middle cerebral artery is the most common site for a stroke, accounting for up to 80% of ischemic strokes that occur in the brain.[6] It arises from the ICA and courses laterally through the sphenoid ridge to the Sylvian fissure. It is responsible for supplying the majority of the lateral hemispheres except for the superior portion of the parietal lobe (ACA) and the inferior portions of the temporal and occipital lobes (PCA). Lenticulostriate branches of the MCA supply the basal ganglia and internal capsule. Damage to the middle cerebral artery on the Left can cause deficits due to damage to Broca's area, Wernicke's area, and contralateral sensorimotor deficits in the upper extremities and head. Damage to the MCA on the right side would spare Wernicke's and Broca's area given the patients' dominant hemisphere is on the left. It is important to note the resultant contralateral sensorimotor deficits in the upper extremities with an MCA stroke versus contralateral sensorimotor deficits in the lower extremities with an ACA stroke.

Posterior Circulation

The posterior cerebral circulation supplies the occipital lobes, cerebellum, and brainstem via branches of the vertebral arteries. It accounts for 20% of the cerebral blood flow.

Basilar Artery

As the vertebral arteries course superiorly into the skull through the foramen magnum, they fuse to form the basilar artery. Often referred to as the vertebrobasilar system, the combination of the vertebral arteries with the basilar arteries provides the posterior supply to the circle of Willis. The basilar artery runs cranially in the central groove of the pons within the pontine cistern. It travels adjacent to CNVI to the upper pontine border and the appearance of CNIII where it terminates. The basilar artery gives off various branches including the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, labyrinth arteries, pontine arteries, superior cerebellar artery, and then finally bifurcates and terminates as the posterior cerebral arteries. Basilar artery occlusion represents up to 4% of all ischemic strokes. Clinical features localizing to the cerebellum or brainstem such as hearing loss, truncal ataxia, extraocular movement abnormalities, and nystagmus, may help to differentiate ischemia in the posterior circulation from other clinical diagnoses.[7] One of the most disabling locations for a basilar artery occlusion is a mid-basilar occlusion with bilateral pontine ischemia. Patients with this condition appear comatose but can be fully conscious and paralyzed with only limited vertical eye movements. This phenomenon termed as "locked-in syndrome" has a high mortality rate of approximately 75% in the acute phase.[7] Another basilar artery occlusion can occur at the distal "top of the basilar syndrome" where the superior cerebellar artery and posterior cerebral artery terminate. It may result in cortical blindness. Physical examination findings may include vertical gaze and convergence disorders, slowed smooth pursuit movements, skew deviation, and convergence-retraction nystagmus and light-near dissociation. Top of the basilar syndrome can have further clinical findings if there is an involvement of the superior cerebellar or posterior cerebral arteries.

Posterior Cerebral Arteries (PCA)

The posterior cerebral arteries are the terminal branch of the basilar artery and supply the overwhelming majority of the occipital lobe. It is joined with the MCA in the circle of Willis via the posterior communicating artery. As the posterior cerebral arteries branch off from the basilar artery, they travel around the midbrain, through the quadrigeminal cistern and with the calcarine artery in the calcarine sulcus. The posterior cerebral arteries have various branches including the posterior communicating artery, the thalamoperforating branches, and the posterior choroidal arteries. The most significant manifestation of a PCA stroke is contralateral hemianopia with macular sparing. The macula is spared due to the dual collateral circulation provided by the MCA. If the PCA stroke involves the dominant hemisphere (usually left) patients may exhibit alexia without agraphia (patients can write but cannot read). Larger infarcts involving the internal capsule and thalamus may cause contralateral hemiparesis and hemisensory loss.

Watershed Regions

Watershed regions are regions that receive dual blood supply from the most distal branches of two large arteries. Watershed zones in the brain are between the anterior/middle cerebral arteries and between the posterior/middle cerebral arteries. Because of the immensity of the middle cerebral artery, a third watershed region may be identified between the superficial and deep vascular territories of the middle cerebral artery. Although watershed regions have a dual blood supply because they are the most distal branches to receive vascular supply they are the first areas to be affected by ischemic events; this can present in patients with severe hypotension or classically a patient who experienced a myocardial infarction and suddenly has CNS effects. Watershed infarctions typically lead to an interesting pattern of weakness affecting more proximal than distal extremities called "man-in-a-barrel." Watershed infarctions of the dominant hemisphere may cause different forms of transcortical aphasia with unusually normal repetition including echolalia and perseverations.

Surgical Considerations

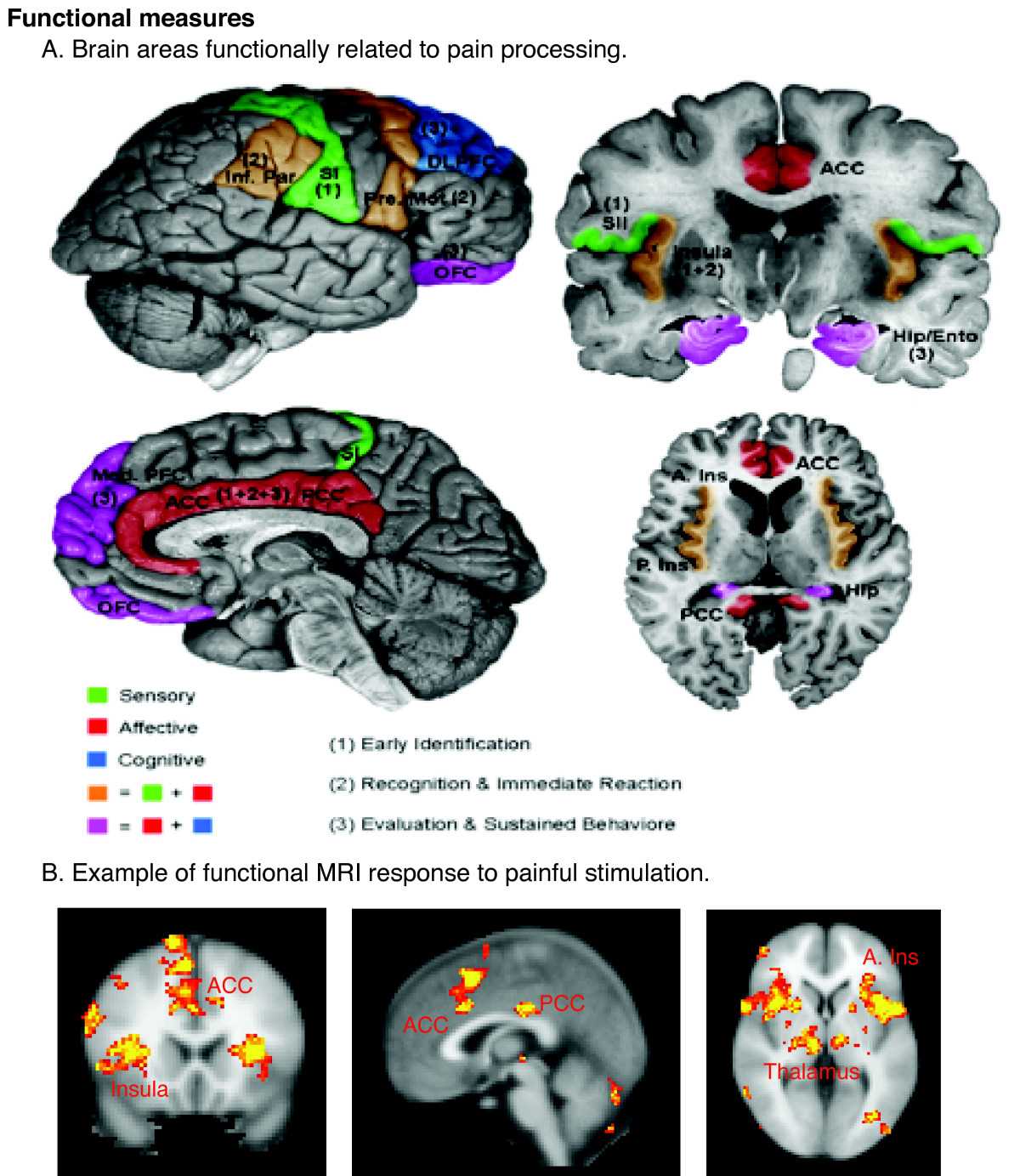

Functional magnetic resonance imaging helps in the pre-operative planning for tumors located in and around the eloquent cortex of the cerebrum. The eloquent cortex controls important bodily functions and the damage to which can cause significant neurological deficits. Examples include the primary motor / somatosensory / visual / auditory cortices and the Wernicke's and Broca's areas.

Clinical Significance

Neural Tube Defects

If the neuropores fail to fuse during the 4th week, a persistent connection between the amniotic cavity and the spinal canal results. This open connection commonly correlates with maternal diabetes and low folic acid intake during pregnancy. In most cases of neural tube defects, maternal serum markers such as alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) will be elevated (except spina bifida occulta). Increased acetylcholinesterase in the amniotic fluid may also act as a confirmatory test.

Spina Bifida Occulta

This condition is due to the failure of the caudal neuropore to close but does not involve any herniation, usually seen at lower vertebral levels and with an intact dura mater. Common presentations of spina bifida are a tuft of hair or dimple present at the level of the bony defect.

Meningocele

This condition occurs if the meninges (but no neural tissue) herniate through the bony defect; this is commonly associated with spina bifida cystica.

Meningomyelocele

This occurs if the meninges and neural tissue (cauda equina) herniate through the bony defect.

Myeloschisis

Also known as rachischisis, this occurs with unfused neural tissue exposure absent skin or meningeal covering.

Anencephaly

When the rostral neuropore fails to close, the forebrain does not develop, and patients will present with an open calvarium. Due to a lack of forebrain development, there is no swallowing center in the brain that presents with polyhydramnios in utero.

Holoprosencephaly

In normal gestation, the left and right hemispheres separate between the 5th to 6th week of gestation. Failure of the hemispheres to separate results in a cyclops like-fetus, with fused basal ganglia, a mono ventricle, and a cleft lip/palate. Mutations in the sonic hedgehog signaling pathway, Trisomy 13 and fetal alcohol syndrome have correlations with this condition.[8]

Lissencephaly

Lissencephaly literally means "smooth surface" and is a rare genetic condition that is characterized by the absence of the folds of the cerebral cortex (agyria/pachygyria) along with microcephaly. The LIS1 gene encodes for the platelet-activating factor which interacts with dynein and dynactin.[9] Because this is critical for neuronal migration, an absence of this interaction results in children presenting with abnormal facies, micrognathia, bitemporal hollowing, muscle spasms, dysphagia, seizures, and profound intellectual disability.

Pachygyria

Pachygyria is also a developmental condition due to abnormal migration of neurons during development that results in abnormally thick gyri. Known as "incomplete lissencephaly," mutations in the KIF5C, KIF2A, DYNC1H1, and the TUBG1 genes have been implicated. Typically, children will present with developmental delay, seizures, and muscle spasms. The degree of disability has shown to correlate with the severity of the cortical malformation.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Stiles J, Jernigan TL. The basics of brain development. Neuropsychology review. 2010 Dec:20(4):327-48. doi: 10.1007/s11065-010-9148-4. Epub 2010 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 21042938]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePirau L, Lui F. Frontal Lobe Syndrome. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422576]

Javed K, Reddy V, Das JM, Wroten M. Neuroanatomy, Wernicke Area. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422593]

Patra DP, Tewari MK, Sahni D, Mathuriya SN. Microsurgical Anatomy of Medial Temporal Lobe in North-West Indian Population: Cadaveric Brain Dissection. Asian journal of neurosurgery. 2018 Jul-Sep:13(3):674-680. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.238077. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30283525]

Ghoneim A, Pollard C, Greene J, Jampana R. Balint syndrome (chronic visual-spatial disorder) presenting without known cause. Radiology case reports. 2018 Dec:13(6):1242-1245. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2018.08.026. Epub 2018 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 30258515]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChiang T, Messing RO, Chou WH. Mouse model of middle cerebral artery occlusion. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2011 Feb 13:(48):. pii: 2761. doi: 10.3791/2761. Epub 2011 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 21372780]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDemel SL, Broderick JP. Basilar Occlusion Syndromes: An Update. The Neurohospitalist. 2015 Jul:5(3):142-50. doi: 10.1177/1941874415583847. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26288672]

Raam MS, Solomon BD, Muenke M. Holoprosencephaly: a guide to diagnosis and clinical management. Indian pediatrics. 2011 Jun:48(6):457-66 [PubMed PMID: 21743112]

Mochida GH. Genetics and biology of microcephaly and lissencephaly. Seminars in pediatric neurology. 2009 Sep:16(3):120-6. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2009.07.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19778709]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence