Introduction

According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, nearly 45,000 rhinoplasties were performed in the United States (US) in 2022, making it the third most popular facial plastic surgical procedure after blepharoplasty and rhytidectomy (2022 ASPS Statistics). Since its first description by John Roe in 1887, both the technical and philosophical approaches to rhinoplasty have evolved substantially. Current indications for rhinoplasty vary widely, including aesthetic enhancement, improvement of nasal airflow, gender affirmation, and oncologic or traumatic reconstruction, each requiring different techniques.[1] Early rhinoplasty was exclusively cosmetic and relied predominantly on reduction maneuvers. As understanding of nasal anatomy advanced, a more proportional approach to the operation developed, incorporating cartilage grafting and suture refinement.

Among the pioneers of rhinoplasty are Jacques Joseph, Maurice Cottle, Samuel Fomon, and Jack Sheen, whose techniques remain in use today to varying degrees. Joseph, a German surgeon at the turn of the twentieth century, emphasized the importance of correcting the nasal septum while reducing the dorsal hump and strongly advocated for the positive psychological effects of aesthetic surgery.[2] Cottle, the founder of the American Rhinological Society in 1954, invented the dorsal preservation technique for hump reduction and recognized the critical role of the nasal septum in shaping the external nose, famously stating, "As the septum goes, so goes the nose."[3] Additionally, Cottle co-founded the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery in 1964 with Goldman and Fomon. Fomon, who served as a US Army Medical Corps officer during World War I, began his career as an anatomist and brought his expertise and passion for teaching to facial surgery. He made education in rhinoplasty theory and technique widely available in the United States during the mid-twentieth century.[4] Sheen is perhaps best known for his seminal textbook Aesthetic Rhinoplasty (1978 1st ed), but his insights opened doors to considering nonCaucasian/ethnic rhinoplasty and revision rhinoplasty. The latter has greatly benefited from the spreader graft technique he described in 1984.[5][6]

As rhinoplasty techniques have evolved, so has the understanding of the complex interplay among aesthetics, breathing, smell, and psychology, all of which are intricately connected within the small confines of the nose. An adverse outcome in these areas can mar the patient's perception of the result, while a good outcome can provide multifactorial benefits. The nose is the central landmark of the face; its proportions and symmetry are directly linked to the overall perception of facial beauty, making the stakes very high when attempting significant modifications.[7] The broad range of nasal appearances among genders, ethnicities, and ages, coupled with anatomical variations from trauma and prior surgery, along with the myriad described operative techniques and the preferences of each patient, makes achieving consistent results challenging even for very experienced surgeons. The nose continues to change shape over time, especially after surgery, and predicting its appearance 20 years in the future is more art than science. For this reason, it has been said that rhinoplasty surgeons can only truly appreciate the extent of their surgical skills as they prepare to retire.

Assessing outcomes in rhinoplasty is complex and challenging, requiring subjective and objective input from patients and surgeons. Surgeons typically rely on physical examinations and comparisons of preoperative and postoperative photographs within the context of normative nasofacial proportions to evaluate a surgery's success. They may also review their revision and complication rates, which are typically reported to be up to 15% and 3%, respectively, and track patient satisfaction.[8][9][10]

Patient-reported outcomes include validated instruments such as the Standardized Cosmesis and Health Nasal Outcomes Survey, Rhinoplasty Outcomes Evaluation, and Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation questionnaires. These tools seek to quantify postoperative quality of life changes and are arguably the most important measures of a surgery's effectiveness.[11][12][13] Consequently, patient selection is considered the most critical predictor of operative success and the most effective means of avoiding litigation or the need for secondary surgery, which is notoriously complex.

Planning revision surgery, whether for cosmetic or functional reasons, must account for the difficulty of meticulous dissection through a previously operated and scarred field, the potential lack of available cartilage for grafting and structural support, injury to the vascularity of the nose and its impact on healing in the septum and skin-soft tissue envelope (SSTE), and the psychological impact on the patient, which may affect rapport and reasonable expectations. These factors, among others, must be considered when performing what is widely regarded as the most complicated of facial plastic surgical procedures.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

A deep understanding of anatomical and physiological relationships within the nose is the cornerstone of good decision-making during rhinoplasty. Modifying 1 nasal structure will frequently impact others and affect the overall appearance of the nose and face. Common examples of these unintended consequences, or the "Newton third law of rhinoplasty" (every action has an equal and opposite reaction), include tip rotation after cephalic trimming, increased alar flare after tip deprojection, tip deprojection after opening the nose, tip rotation and columellar retraction after septocolumellar suturing, and many others.

External Nose

The external nose consists of a bony and cartilaginous framework enveloped by muscle, soft tissue, and skin.

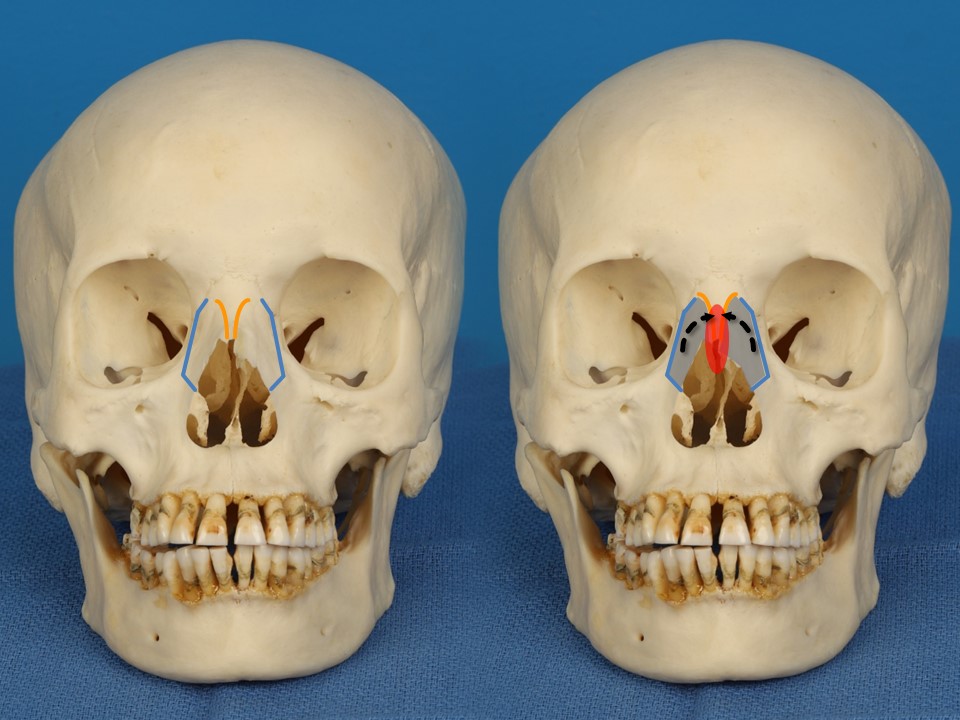

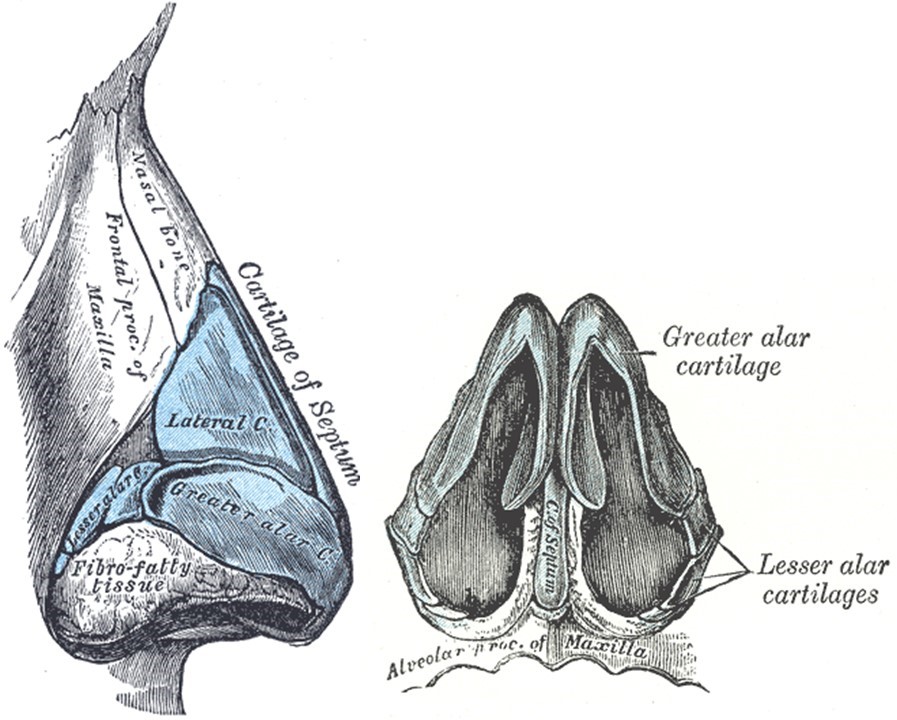

Nasal bones and cartilage

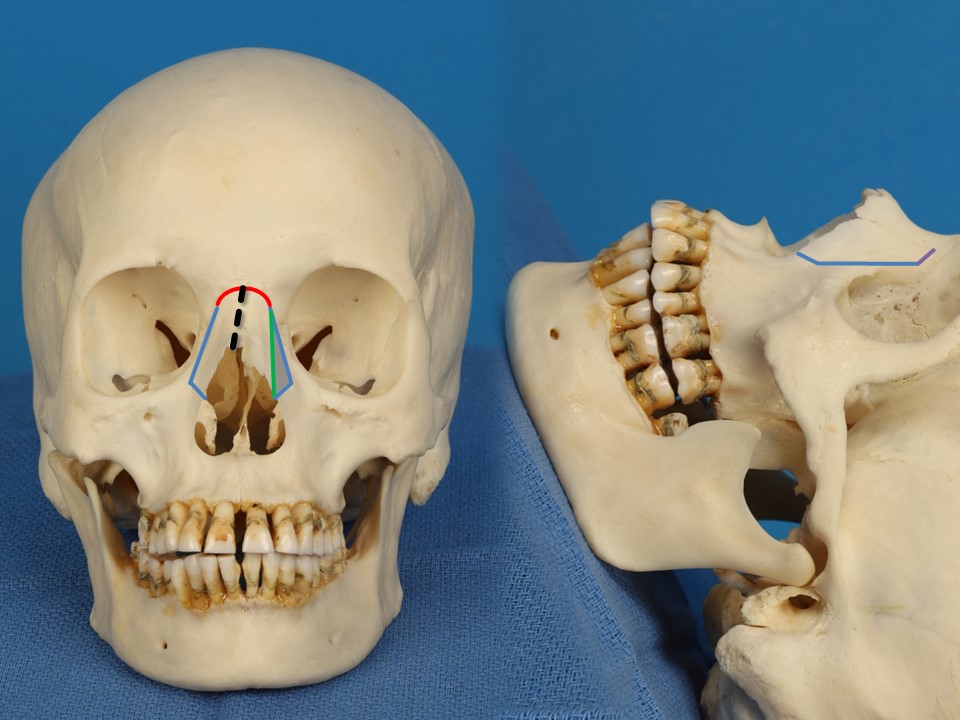

The upper third of the nose, or "bony vault," is composed of the paired nasal bones medially and the frontal processes of the maxillae laterally (see Image. External Nasal Skeleton), which constitute the bony pyramid. Medially, the nasal bones join with the ethmoid bone's perpendicular plate—the bony septum's upper component—which extends inferiorly and posteriorly to the bony vault. The middle third, or "midvault," is formed by the upper lateral cartilages, which attach to the nasal bones cranially.

The nasal bones overlap the upper lateral cartilages for 4 to 5 mm on either side of the rhinion, providing additional support for the midvault. The rhinion, the point at which the nasal bones end in the midline and give way to the cartilaginous septum, is an important anatomical landmark concerning the aesthetics of the dorsal contour (see Image. External Nasal Anatomy). The upper lateral cartilages fuse with the cartilaginous septum along the dorsal midline of the nose, forming an angle classically described as 10 to 15 degrees.[14] This narrow portion of the nasal passage is called the internal nasal valve. During surgical maneuvers, it is important to maintain or widen this angle to optimize postoperative airflow.

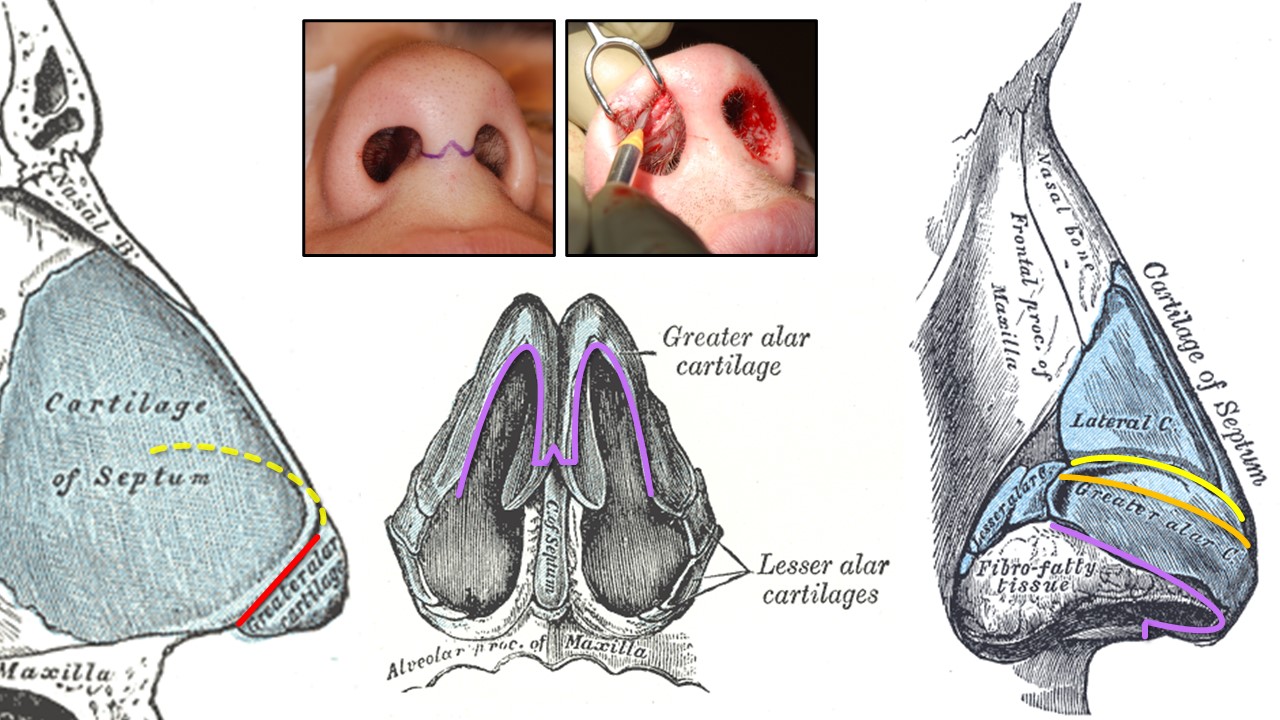

The 2 lower lateral, or alar, cartilages each consist of a lateral and a medial crus, which support the columella and the lateral aspect of the nasal tip, respectively. Between the medial and lateral crura is a bend known as the middle or intermediate crus. The intermediate crura constitute the domes underlying the tip-defining points of the nose, which are the small, paired reflections seen in direct lighting (see Image. External Nasal Anatomy).

The nasal tip has 3 major support mechanisms: the size/shape/resiliency of the lower lateral cartilages, the attachment of the lower lateral cartilages to the upper lateral cartilages at the "scroll" region, and the attachment of the medial crura of the lower lateral cartilages to the caudal septum, and 6 minor tip support mechanisms: the interdomal ligaments, the SSTE, the anterior septal angle, the anterior nasal spine, the membranous septum, and the sesamoid cartilages).[15] They also provide the framework for the external nasal valves, the regions bounded by the caudal margins of the lower lateral cartilages, the septum and columella, and the nasal sill. Of note is that the nasal alae do not contain cartilage but rather fibrofatty tissue, as the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages pass just superior to the alar grooves.

Muscles

The main mimetic muscles of the nose are the nasalis, dilator naris, levator labii alaeque nasi, and depressor septi. These muscles are enclosed and interconnected by a fibrous fascia that constitutes part of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system of the face. The clinical significance of the nasal muscles is easily underestimated. Still, they are important for maintaining patency of the external nasal valve, as evidenced by the unilateral nasal airway obstruction commonly experienced by patients with Bell palsy and other types of facial paralysis.[16] For this reason, some surgeons prefer to raise local flaps in a subdermal plane rather than the deeper and better-perfused submuscular plane when performing nasal reconstruction to avoid malposition of the muscles and potential nasal valve dysfunction.

Septum and skin-soft tissue envelope

While the SSTE of the nose varies greatly in thickness and texture by sex, age, ethnicity, and history of prior surgery or trauma, the tissue covering the rhinion is the thinnest, followed by the upper third, and then lower third, which is the thickest and most sebaceous. The latter's texture resembles that of the forehead and glabella, which are important considerations for reconstruction, particularly with paramedian forehead flaps.[17]

Internal Nose

The internal nose comprises the septum, the turbinates, the olfactory cleft, the lateral nasal wall, and the nasal floor, all covered by mucosa. The septum and the inferior turbinates are the most critical structures with respect to aesthetic and airway concerns.

Septum

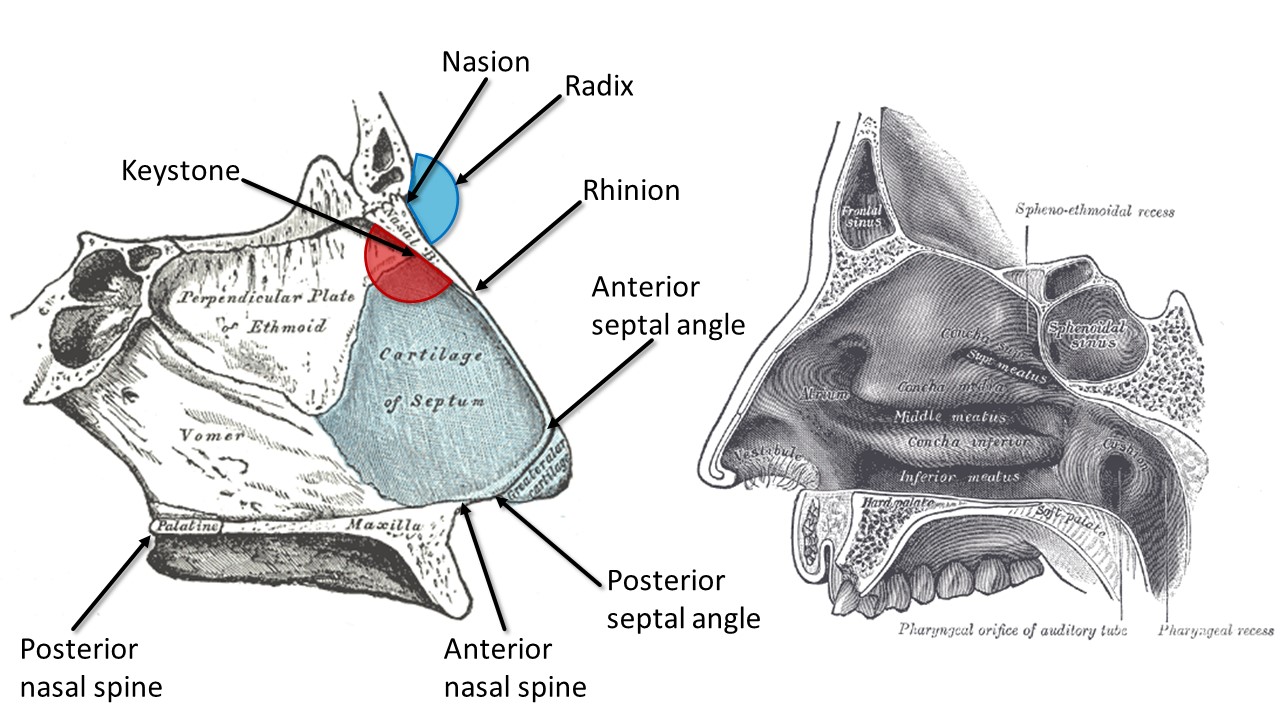

The nasal septum, a rigid structure covered by mucosa, is located in the midline of the nasal cavity, where it separates the left and right nasal passages and constitutes the principal support of the external nose. The anterior aspect of the septum is occupied by the quadrangular cartilage, while the posterior portion is bony.

The bony components are the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid superiorly, the vomer posteriorly, and the maxillary crest inferiorly (see Image. Internal Nasal Anatomy). The junction of the quadrangular cartilage and the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone at the dorsal aspect of the septum is known as the "keystone" area, and its preservation during surgery is critical for the maintenance of support for the external nose and avoidance of a saddle deformity (see Image. Saddle Nose).

The septum is the primary determinant of the dorsal projection of the nose in the midvault, and the caudal portion of the septum influences how low the columella hangs below the alar margins; septal deviations in these areas are liable to result in visible distortion of the external nasal contour. At the junction between the dorsal and caudal margins of the septum lies the anterior septal angle, which supports the nasal tip and contributes to nasal projection. When performing a septoplasty or septal cartilage harvest, it is important to leave an L-shaped strut of 10 to 15 mm in width along the dorsal and caudal margins of the quadrangular cartilage to provide adequate structural support for the nose. Similarly, the keystone and the junction of the caudal septum and the anterior nasal spine should ideally be left intact or carefully reconstructed if violated.

The superior aspect of the septum also constitutes 1 of the boundaries of the internal nasal valve, along with the caudal margin of the upper lateral cartilage and the head of the inferior turbinate. The internal valve is the narrowest portion of the nasal passage, with an angle ranging from 52 degrees if completely patent to 0 degrees if obstructed by the septal swell body, a collection of glandular tissue within the submucosa of the superior aspect of the nasal septum encountered in about half of patients.[14]

Turbinates

Turbinates are bony outgrowths along the lateral nasal wall covered by mucosa and containing vascular erectile tissue. These structures form pathways wherein the air flows and is warmed and humidified. They also help remove particles from the inspired air and assist in regulating the airflow by contracting and expanding.

Within each nasal passage are superior, middle, and inferior turbinates, with the superior and middle being processes of the ethmoid bone and the inferior turbinate, or concha, being a separate bone altogether (see Image. Internal Nasal Anatomy). Most of the airflow passes below the middle and inferior turbinates. Conditions like rhinitis and septal deviation can induce turbinate hypertrophy, obstructing airflow. Turbinate reduction is commonly performed concurrently with septoplasty and septorhinoplasty.

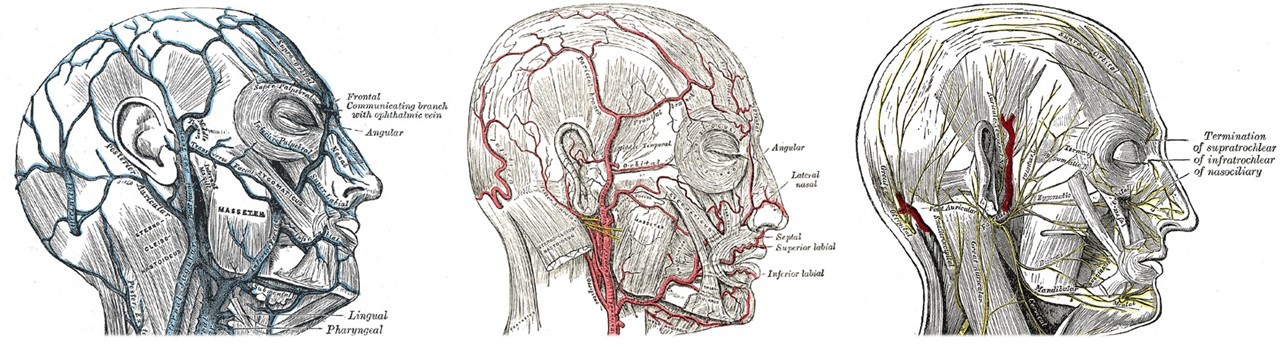

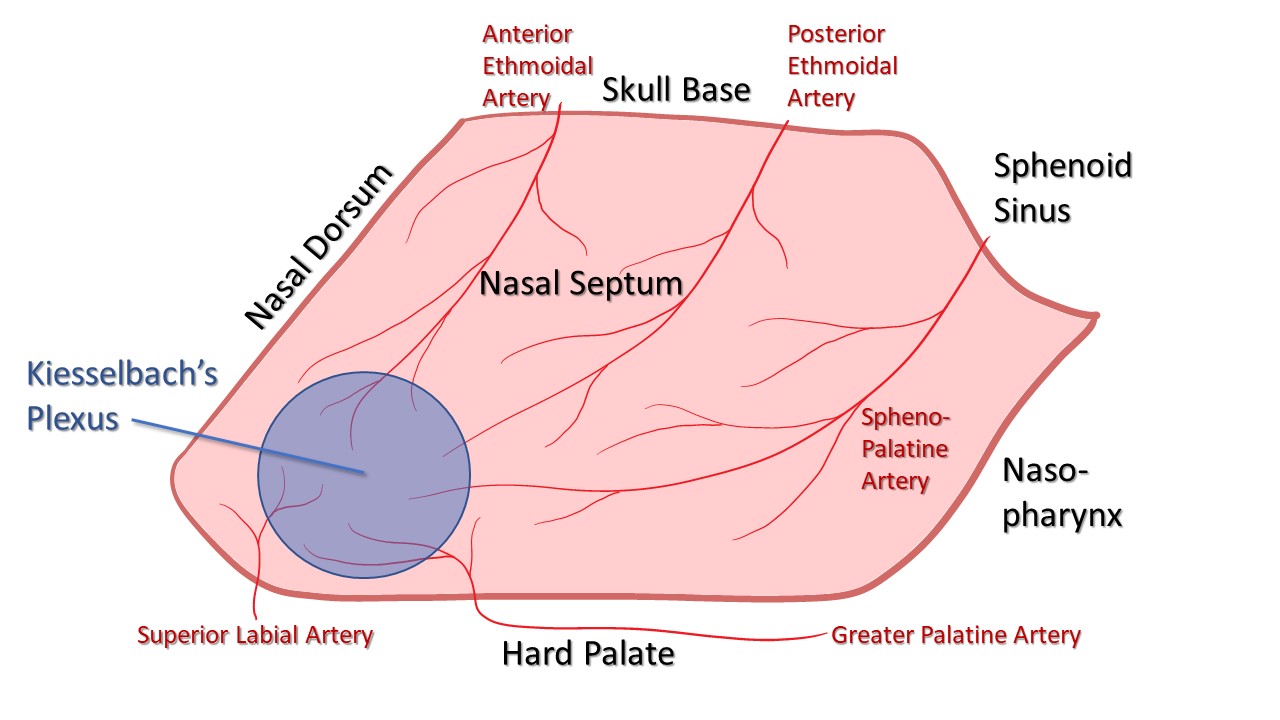

Nasal Blood Supply

The nose has a rich vascular network (see Image. Veins, Arteries, and Nerves of the Face and Scalp), allowing for the broad undermining of the SSTE without compromising tissue perfusion. The main nasal arteries are the supratrochlear and the facial artery, branches of the internal and external carotid, respectively. Both these arteries, together with branches of the ascending columellar arteries, widely anastomose, forming a robust network. Blood is supplied to the nasal septum by the anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries, originating from the ophthalmic artery (a branch of the internal carotid artery), the sphenopalatine artery (a branch of the external carotid artery), and the septal branch of the superior labial artery (a branch of the facial artery). All these branches come together in a network known as the Kiesselbach plexus, the most common site from which epistaxis originates (see Image. Blood Supply of the Nasal Septum). Venous drainage primarily flows through tributaries of the facial vein.

Nasal Innervation

The motor supply to the nose muscles comes via the facial nerve's buccal branch. Sensory innervation is more complicated, with multiple branches of the ophthalmic nerve (cranial nerve [CN] V1), the infratrochlear and external nasal nerves, the maxillary nerve CN V2, and the infraorbital and nasopalatine nerves—contributing to a mosaic of sensory distributions (see Image. Veins, Arteries, and Nerves of the Face and Scalp). The nose also provides special sensation via olfactory nerve filaments that traverse the cribriform plate to innervate the olfactory epithelium, which lines the olfactory cleft at the roof of the nasal cavity and covers portions of the superior septum and the superior turbinates.[18]

Indications

Rhinoplasty is performed for functional problems, aesthetic issues, or, more often, a combination of both. Patients who present with either nasal obstruction or cosmetic concerns often overlook the impact that correcting one issue may have on the other. Without appropriate preoperative counseling and a surgical plan that balances form and function, these patients may not be satisfied postoperatively.[19] This underscores the importance of establishing a strong surgeon-patient rapport.

While much has been written about the difficulty of identifying the ideal candidate for rhinoplasty, there is no proven way to consistently recognize high-risk patients who may be unhappy with the outcome. Therefore, surgeons must physically and psychologically evaluate patients to predict whether an operation will be beneficial. During the initial visit, the priority is to ascertain the patient’s goals and determine if their expectations are achievable, as postoperative patient satisfaction is the primary determinant of surgical success.[20] By asking open-ended questions about the patient's life and context, such as family composition and social relationships, the surgeon can gather verbal and nonverbal cues to understand the patient. As a guide, the acronym SYLVIA (secure, young, listens, verbal, intelligent, attractive) has been used to describe a good rhinoplasty candidate, while SIMON (single, immature, male, overexpectant, narcissistic) represents patients who may be unsuitable for surgery.

Regarding the nose itself, it is important to discuss the specific features patients dislike, such as dorsal humps, nasal deviation, or tip asymmetry, and explain systematically what can be improved and how. Many surgeons use 2- or 3-dimensional computer simulation software to illustrate an approximation of the surgical result.[21] This tool has gained popularity, and in a 2017 survey, 63% of rhinoplasty surgeons reported using it during consultations.[22] While computer simulation can help establish reasonable expectations for some patients, others may fixate on the simulated outcome and find it difficult to be satisfied with anything less. Consequently, a significant number of surgeons have chosen not to adopt computer simulation.

While establishing which patients are good candidates for primary rhinoplasty can be challenging, determining who would benefit from revision rhinoplasty can be even more complex. These patients' expectations are shaped by their previous experiences, which may lead them to have a better understanding of what to anticipate. Conversely, this may cause them to be less reasonable, expecting the new surgeon to fix what they perceive as a "botched" operation by the previous surgeon. The surgical techniques employed in revision surgery may differ significantly from those used in primary rhinoplasty. The second or third operation might be more aggressive than the first, or it could be minimally invasive and aimed at addressing 1 or 2 small deficiencies. These preoperative decisions will inform the surgeon's operative approach: whether to open the nose, operate endonasally, or deliver the nasal tip.

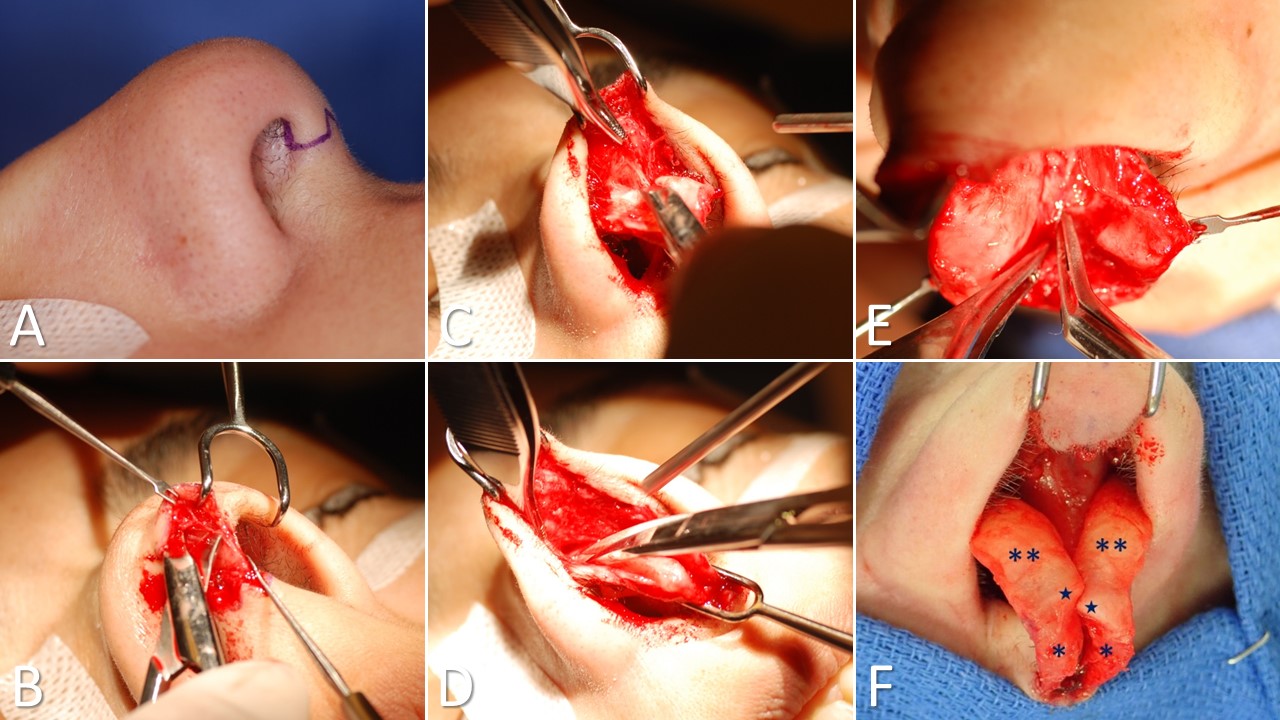

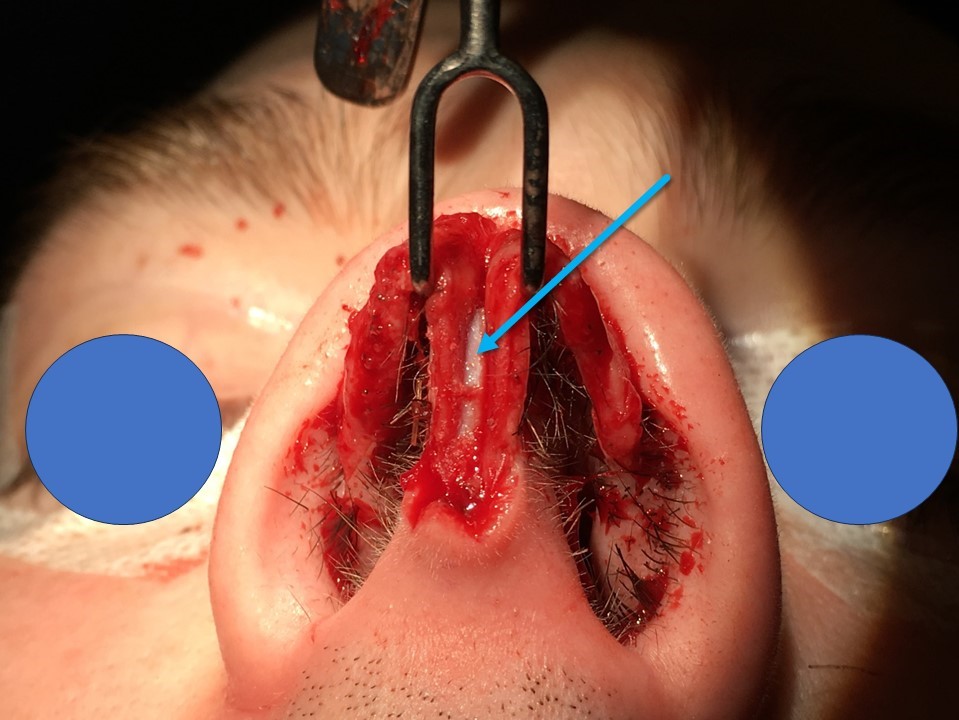

The open approach exposes the entire cartilaginous nasal skeleton and provides excellent access to the bony vault as well (see Image. Open Rhinoplasty Approach). This method can be used for primary and revision rhinoplasty. However, opening the nose a second or third time is far more challenging due to scar tissue and previous manipulation of the cartilage. Tip modification surgery is most easily performed via the open approach because of the enhanced exposure, making it the preferred method in many teaching institutions.[23] The tip is also exposed when a delivery approach is selected, though it requires separating the tip into the left and right domes, which are then distorted as they are delivered into their respective nares (see Image. Tip Delivery Rhinoplasty). Many experienced surgeons employ the tip delivery approach, but it requires substantial skill and is challenging to master.

The endonasal approach allows modification of the upper third of the nose, particularly osteotomies and dorsal hump reduction. Spreader grafts can also be placed endonasally, though many surgeons prefer the open approach to ensure precise placement. Some maneuvers within the lower third are possible endonasally, such as alar batten graft placement, rim graft placement, and cephalic trimming. However, more delicate interdomal and transdomal suturing or nuanced grafting is often performed via an open approach. For some patients, the primary indication for the surgical approach is the anticipated recovery. The endonasal and tip delivery approaches result in decreased severity and duration of postoperative edema compared to the open approach and avoid creating a columellar scar.

Contraindications

Common contraindications for rhinoplasty include:

Psychiatric Disorders

Body dysmorphic disorder is characterized by an excessive preoccupation with an imagined or barely noticeable defect in appearance.[24] As a result, patients with this condition have difficulty socializing, poor quality of life, and higher rates of depression and suicide.[25] Surgeons need to recognize this diagnosis early in the preoperative process because symptoms may worsen postoperatively, and it is doubtful that a patient with body dysmorphic disorder will be satisfied with the results of a rhinoplasty. Unfortunately, no validated instrument can consistently diagnose body dysmorphic disorder. Similarly, patients with poorly controlled depression are at risk for decompensation postoperatively; surgery should be deferred until mood symptoms stabilize.[26] If clinical suspicion of psychiatric disorders arises, referral for preoperative behavioral health evaluation is imperative.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

This common condition is characterized by repeated airway obstruction episodes and sleep arousal. Patients with obstructive sleep apnea are known to have a higher risk of perioperative complications.[27] The diagnosis is often suspected based on the patient’s symptoms and body habitus, although it can be asymptomatic. Screening questionnaires are available but have limited specificity. Polysomnography is the gold standard for diagnosing obstructive sleep apnea.

Although it is not an absolute contraindication, patients with this condition should be advised of the risks, and preoperative measures like using a continuous positive airway pressure device should be implemented to reduce complication rates. A plan should be in place to admit patients with obstructive sleep apnea for overnight observation after surgery if they are having difficulty maintaining oxygen saturation in the recovery room.

Cocaine Use

Inhaled cocaine induces intense vasoconstriction as well as chronic mucosal inflammation due to contaminating additives.[28] Rhinoscopy findings can vary from mild erythema to large septal perforations. Patients who are actively using cocaine are also more likely to have postoperative complications like septal collapse or impaired mucosal healing, and they should be advised to avoid elective nasal surgery. Patients who have previously used cocaine may be considered for nasal surgery on an individual basis, bearing in mind that healing impairment may persist in the long term.

Tobacco Smoking

Although it appears that tobacco smoking does not significantly affect nasoseptal surgery outcomes, patients should be encouraged to quit before the procedure because of the myriad harmful systemic effects of tobacco.[10][29]

Bleeding Disorders

Impaired coagulation may cause postoperative complications and make the surgery itself more challenging. Patients should be asked about a history of excessive bruising or bleeding, consumption of drugs, supplements, or vitamins that alter the coagulation cascade, or history of thrombotic events in the past. If possible, any drugs, vitamins, or supplements that impair coagulation should be suspended preoperatively.Examples of over-the-counter supplements that may exacerbate bleeding include aloe, chamomile, chondroitin, cranberry, dong quai, echinacea, ephedra, evening primrose, fenugreek, feverfew, flaxseed, garlic, ginger, gingko, ginseng, goldenseal, glucosamine, grapefruit, green tea, kava, meadowsweet, milk thistle, oregano, red clover, saw palmetto, turmeric, and white willow.[30]

Age

Surgery is usually performed when the nasal skeleton has developed completely, and the nasal shape is not expected to change significantly for the foreseeable future. This age is approximately 15 for females and 17 for males.

Recent Prior Rhinoplasty

Generally, patients who underwent previous rhinoplasty and are unhappy with the results should wait at least 1 year before assessing the final result and considering a revision procedure.

Equipment

Equipment required off the surgical field includes:

- Preoperative photographs posted for reference

- Tape or adhesive film dressings to protect the eyes

- Cottonoid pledgets for nasal packing, soaked in decongestant (0.05% oxymetazoline or 4% cocaine)

- Local anesthetic (1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine) in 3 cc syringes with 27 gauge, 1.5-inch needles

- Nasal speculum (Vienna)

- Bayonet forceps

- Headlight

Equipment required on the surgical field includes:

- Skin marker

- Sutures (7-0 polyglactin, 6-0 polypropylene, 6-0 plain gut, 5-0 polydioxanone, 5-0 chromic gut, 4-0 chromic gut, 3-0 nylon)

- Double-prong skin hooks (Joseph 2 mm, 7 mm, and 10 mm; Guthrie scleral hooks)

- Scalpels (Bard-Parker #15, #15c, #11; #6700 Beaver; dermatome blade for carving costal cartilage)

- Nasal specula (Vienna, Cottle, Killian)

- Scissors (Converse, Wilmer, Joseph, Giunta, Cottle, Fomon upper and lower lateral, Gorney shears, Mayo, iris)

- Elevators (Cottle, Freer, Pierce, Woodson, Joseph, Sayre, Boies)

- Osteotomes and mallets (Anderson-Neivert, Rubin)

- Cartilage crusher (Cottle)

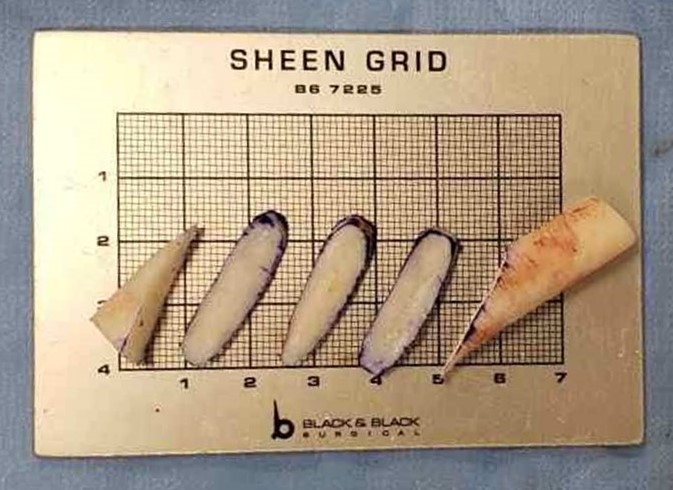

- Cutting grid (Sheen)

- Caliper (Tebbetts)

- Rasps (coarse and fine diamond, push and pull steel)

- Forceps (Adson-Brown, Cushing-Brown bayonet, dressing bayonet, Castroviejo 0.5 mm, Takahashi, Blakeseley)

- Needle holders (Halsey, Castroviejo)

- Rongeurs (Jansen-Middleton open and closed biting)

- Suction (Frazier tip, 10 Fr)

- Retractors (Aufricht, Bernstein, Gruber)

- Bipolar cautery forceps

- Thrombin-gelfoam hemostatic matrix

- Fibrin glue

- Gauze

- Cotton-tipped applicators

- Piezotome

- Tape dressings

- Splints or packing (Doyle splints or iodine and petrolatum-impregnated gauze)

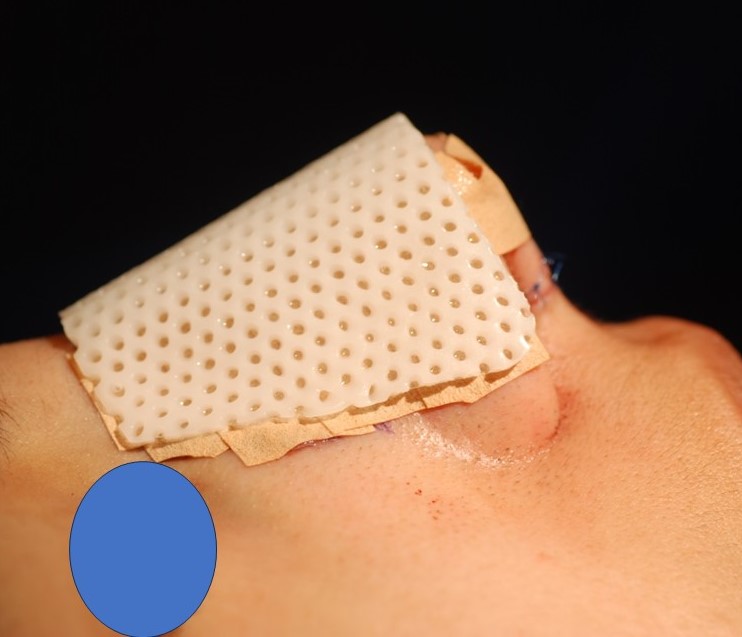

- Nasal cast (thermoplastic or malleable)

- Saline irrigation and bulb syringe

- Antibiotic ointment (mupirocin or similar; petroleum-based ointments, such as bacitracin, are avoided because of the risk of myospherulosis)

- Long-acting local anesthetic (liposomal bupivacaine)

- Microdebrider for turbinoplasty (2 mm)

Personnel

Rhinoplasty is typically performed by an otolaryngologist, facial plastic surgeon, or a plastic surgeon. Some oral-maxillofacial surgeons are also trained to perform rhinoplasty. While a surgical assistant is not necessary, one may be helpful for retraction, suctioning, and suture cutting. A surgical technician or scrub nurse is, however, essential. A rhinoplasty will also need a circulating nurse and an anesthesia provider if performed under general anesthesia. These procedures are typically performed in an ambulatory setting unless social circumstances preclude this option, so an escort to drive the patient home is mandatory.

Preparation

Preoperative

The initial preparation for rhinoplasty consists of appropriate counseling and an examination. Eliciting a history of prior nasal surgery and the patient's experience with both it and the previous surgeon can be informative for the sake of operative planning and for establishing reasonable expectations for the patient and the new surgeon alike. Any psychiatric comorbidities, such as a tendency towards depression or body dysmorphic disorder, should be recognized at this time so that either appropriate treatment planning (to include behavioral health referral) can be initiated or surgery can be deferred. Other medical problems, including obstructive sleep apnea, recurrent or chronic sinusitis, hypertension, and bleeding diatheses should be discussed, as they may necessitate additional surgical interventions or medical management. Recreational drug use may have an impact on the selection of anesthetic agents and analgesic medications, but cocaine use in particular may require cancellation or delay of surgery due to the adverse effects it has on the vascularity of the nasal mucosa.

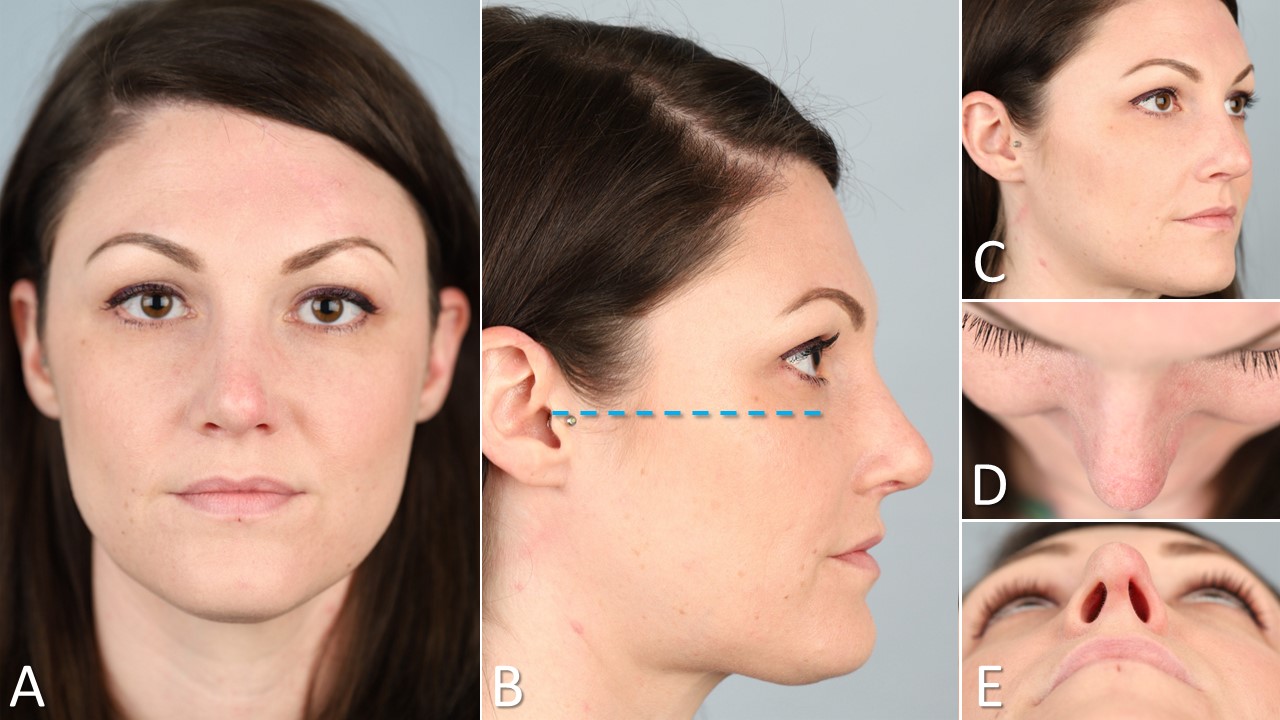

As part of the examination, high-quality preoperative photographs should be taken with the patient's face aligned in the Frankfort horizontal plane (a line running between the inferior orbital rim and the top of the external auditory canal should be parallel to the floor), including the following views: frontal, bilateral profiles, bilateral three-quarter view, basal view, and dorsal view (see Image. Standard Photographs for Rhinoplasty). These will provide points of reference for counseling and intraoperative decision-making and may be used for medicolegal purposes as well. Counseling will depend largely on the goals of the patient, balancing aesthetic and functional expectations, particularly in the case of reduction rhinoplasty in women. The greatest risk of any facial surgery is dissatisfaction with the cosmetic outcome either immediately or in the future, but other risks include pain, bleeding, bruising, swelling, infection, scarring, damage to the SSTE, nasal obstruction, change or decrease in sense of smell, septal perforation, numbness or sensitivity in the distribution of the nasopalatine nerve, cerebrospinal fluid leak, postoperative depression, and need for further surgery.[9] Patients undergoing revision surgery, and those who require post-traumatic or oncologic reconstruction, should also consent to the harvest of tissue at extranasal sites, including conchal cartilage, costal cartilage, and temporoparietal or temporalis fascia; the risks of these graft harvests should be discussed as well.

Nasal analysis and Exeamination

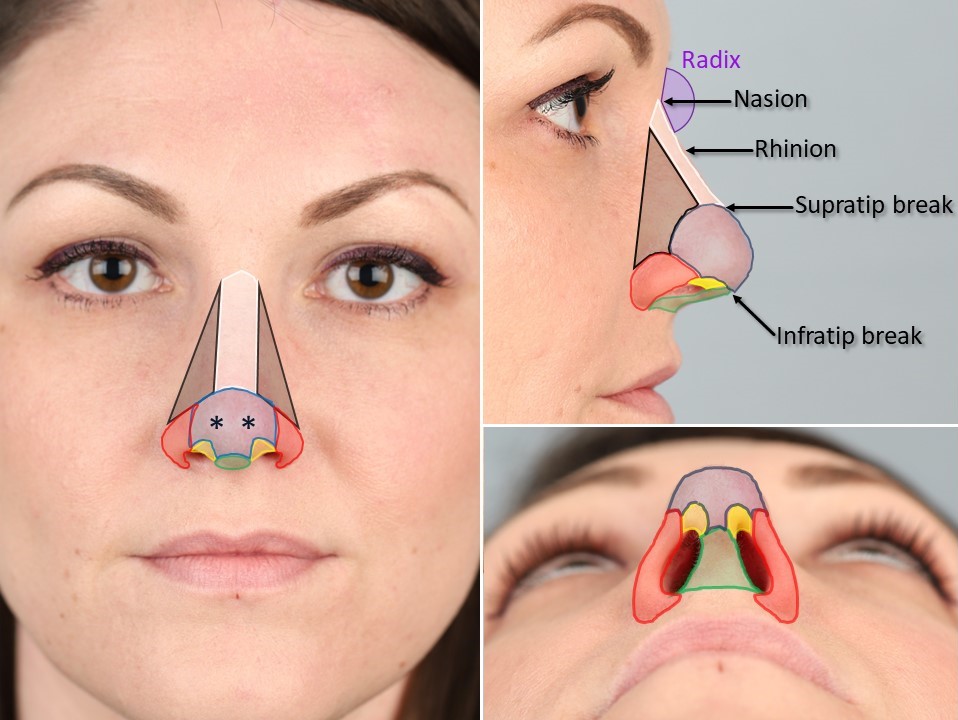

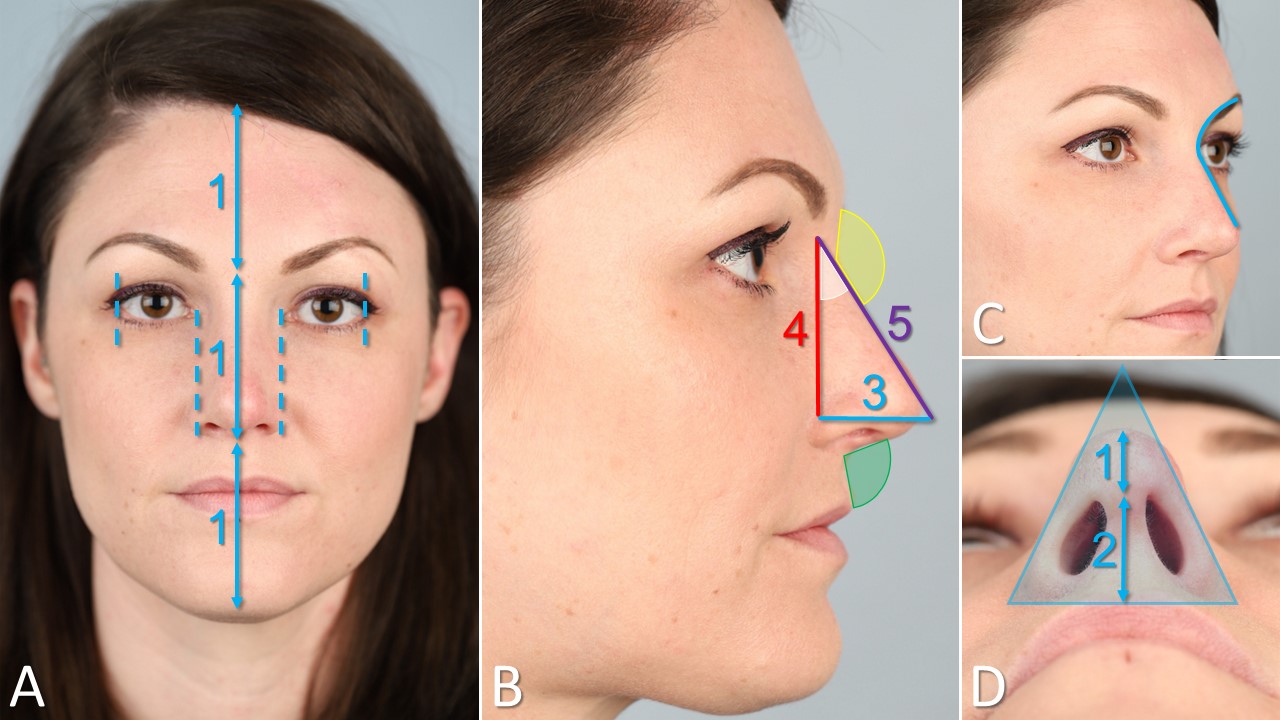

The external nose is divided into 9 aesthetic subunits (dorsum, 2 sidewalls, tip, 2 alae, columella, 2 soft tissue triangles; see Image. External Nasal Anatomy), which are most relevant to oncologic reconstruction; for the purposes of rhinoplasty, the nose is more often divided into upper, middle and lower thirds, as described above. The upper third begins at the nasofrontal suture superiorly and widens as it approaches the middle third. The middle third also widens inferiorly where it merges with the lower third at the scroll. The lower third is the broadest portion of the nose, with the alar base equal in width to the intercanthal distance in Caucasian individuals or as wide as the intercaruncular distance in individuals of Sub-Saharan African descent.[31]

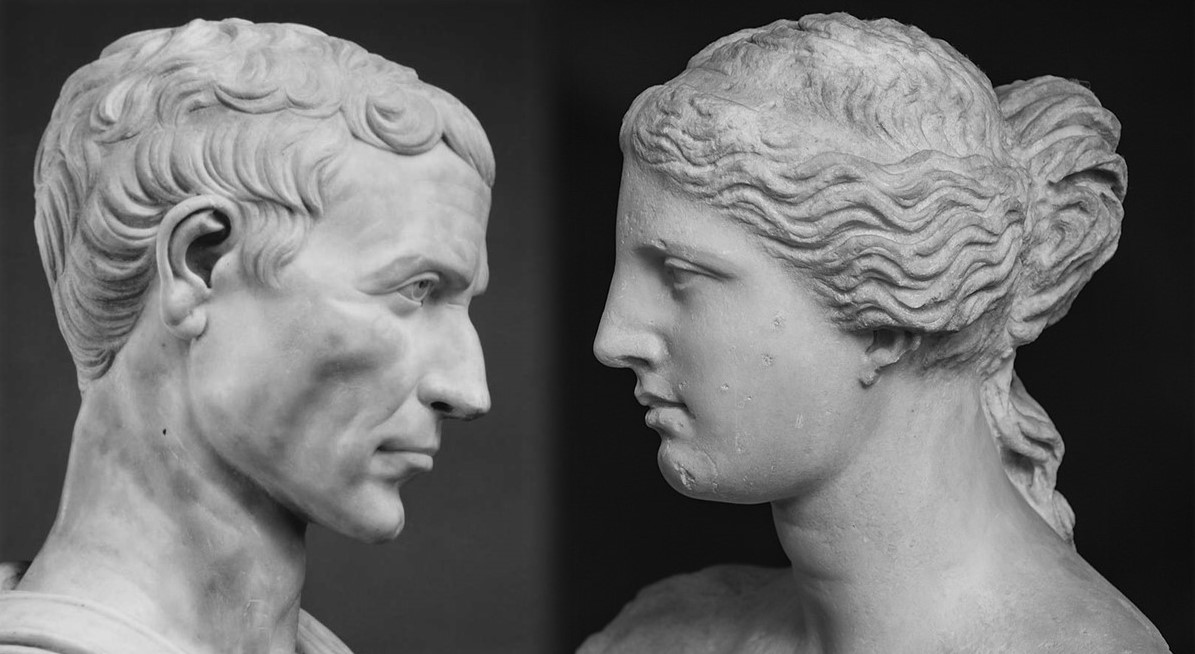

The most superior extent of the nose is the nasofrontal suture, whose midline point is known as the nasion. The nasion is the deepest portion of the region known as the radix, or root of the nose. The depth of the radix is determined by the position of the nasofrontal suture relative to the prominence of the glabella and of the rhinion and therefore plays an important role in the perception of a nose's dorsal projection, particularly if there is a hump. For example, a nose with a deep radix and prominent dorsum will be seen to have a hump (a "Roman" nose), whereas a nose with an equally prominent dorsum and a shallow radix, in which the nose seems to join directly with the forehead, will not be perceived as having a hump at all (a "Greek" nose; see Image. Roman and Greek Noses). In this way, the nose can be viewed through a Taoist lens; just as there can be no perception of light without darkness to which it can be compared, or heat without cold, the radix defines the hump and vice versa. Ideally, the nasofrontal angle, which is centered at the radix, should measure approximately 115º to 130º in a Caucasian individual, but less in Asian, Latin, and African individuals.

The differences stem from variations in overall proportions by race; Caucasian noses tend to have a leptorrhine configuration (relatively slim and highly projected with a robust osteocartilaginous framework) while Sub-Saharan African noses are typically platyrrhine in appearance (flatter and wider with smaller nasal bones and less septal cartilage) and Asian, Middle Eastern and Latin noses lie somewhere on a spectrum between the 2 extremes (mesorrhine).[32][33] Admittedly, specific ethnic nasal features are far more nuanced than the simple framework the 3 categories suggest; however, this classification scheme does provide a foundation upon which rhinoplasty surgeons can communicate and refine techniques.

As the examination progresses down the nose, the symmetry, particularly with respect to deviations from the midline, should be assessed. A nose whose upper, middle, and lower thirds all point in the same direction away from the midline is known as a "deviated" nose, whereas a nose with a C-shaped curvature, commonly resulting from a blow to the side of the nose, is referred to as "crooked" or "twisted." The symmetry of the face should be evaluated as well because hemifacial microsomia is common and can have a major impact on both the appearance of the nose and the extent to which deviations can be straightened. Contour irregularities at the rhinion, such as small projections or "horns" may be best appreciated in the profile or three-quarter views, or even by palpation. Stigmata of prior surgery should be identified, such as an open roof deformity, in which a dorsal hump with a large bony component was removed and the cut medial edges of the nasal bones are palpable or visible due to a midline gap in the bony vault.

Other common sequelae of rhinoplasty include saddling of the midvault due to inadequate support of the dorsal septum and the "inverted V" deformity, in which the caudal edges of the nasal bones are sharply visible due to descent of the upper lateral cartilages into the nose. The latter typically occurs as a result of an endonasal dorsal hump reduction that disarticulates the upper lateral cartilages from the dorsal septum but does not resuspend them to reconstruct the midvault. Failure to reduce the cartilaginous portion of a dorsal hump adequately relative to the bony portion (or over-resection of the bony portion relative to the cartilaginous portion) may cause a "polly beak" deformity, in which the supratip portion of the middle third appears rounded and over-projected, conveying the appearance of a parrot's bill. Tip ptosis and development of scar tissue in the supratip region can further exacerbate this deformity, which must not be confused with a true dorsal hump, as they are managed differently.

Evaluation of the middle third should also include assessment of the internal nasal valves with a modified Cottle maneuver, in which the patient is asked to inhale through the nose with and without a small instrument (cerumen loop or the back end of a cotton-tipped applicator, for example) supporting, but not lateralizing, the upper lateral cartilage. Substantial subjective airflow improvement with support indicates that opening the internal nasal valve during surgery may be beneficial. A similar maneuver may be performed at the external nasal valve; alternatively, some surgeons prefer to look for the dynamic collapse of the alae with inspiration as an indicator of external nasal valve insufficiency. If the patient demonstrates symptomatic dynamic alar collapse, marking the points of maximum collapse preoperatively will enable the surgeon to reinforce the external nasal valves accordingly.

The lower third is the most complicated aspect of the nose to manage due to the complicated relationships among its aesthetic subunits, its respiratory function, and its ethnic variations (see Image. Nasal Analysis). The ideal projection of the nasal tip out of the facial plane may be measured against the standards described by Simons, Goode, and Crumley (Simons: tip projection should equal the height of the cutaneous upper lip, Goode: tip projection to nasal length ratio should be 0.55-0.6:1, Crumley: tip projection, nasal height, and nasal length should constitute a 3:4:5 Pythagorean triangle), although these proportions really only hold true for leptorrhine noses, while mesorrhine and platyrrhine patients will have somewhat lesser projection.[34]

Similar to the dorsal projection, however, the perceived projection of the nasal tip is influenced by the context of the face as a whole, particularly the projection of the chin. If the anteriormost point of the chin, the pogonion, sits behind the nasion when the face is aligned in the Frankfort horizontal plane, the nasal tip will appear more projected, but if the chin is more prominent, the nasal tip will seem less projected. The nasolabial angle in a leptorrhine nose is classically described as 95º to 110º in women (with greater rotation acceptable for shorter women) and 90º to 95º for men, but somewhat less for those with mesorrhine and platyrrhine noses, particularly for Middle Eastern individuals, who may have rather acute nasolabial angles.

When viewed from the side, the length of the nasal tip lobule should equal the width of the ala. When viewed from beneath, the base of the nose should present a generally triangular shape (vs trapezoidal) and the length of the infratip lobule should measure half the length of the columella. The columella, when viewed from the side, should present 2 to 4 mm of height visible below the alar margin. Less columellar show indicates retraction of the caudal septum, likely due to trauma or prior surgery, and more columellar show signifies either a retracted nasal ala or a hanging columella. The width of the base of the nose should be assessed as well, both the alar base width and the alar flare. The alar base width is the distance from the point at which the ala meets the face at the alar crease on the right side to the same point on the left. This distance should equal the intercanthal distance in a leptorrhine nose.

Alar flare, if present, is the distance beyond the alar base width that the lateral extent of the ala reaches due to its convexity; this is commonly seen in platyrrhine noses. Last, the lower lateral cartilages themselves should be assessed in terms of shape and strength. Gentle palpation of the tip of the nose will provide an idea of how strong the cartilages are and how much support there is for the nasal tip. Broad lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages will cause excessive supratip fullness, while lateral crura that have been excessively narrowed during prior surgery will often produce alar retraction and/or upward tip rotation. Asymmetries in the lower lateral cartilages, such as lateral crural recurvature that narrows the external nasal valve and bossae that disturb the smooth contour and symmetry of the nasal tip, may also result from prior surgery or trauma, or may be congenital; these asymmetries should all be identified preoperatively.

The final portion of the physical examination involves anterior rhinoscopy, which may be supplemented with fiberoptic or rigid nasendoscopy if findings on anterior rhinoscopy do not identify the anatomic etiologies of the patient's functional complaints. The nasal septum should be assessed for deviations, as they can cause symptomatic nasal obstruction. Even for patients without nasal dyspnea, the septum should be visualized to determine the availability of straight cartilage for grafting. For patients who have had prior nasoseptal surgery, the septum should be examined for any perforations, and palpation of the septum with a cotton-tipped applicator will reveal how much cartilage remains to be harvested for grafting.

The vestibules should be inspected without the use of a speculum, which will distort them and make identification of subtle abnormalities like lateral crural recurvature challenging. The turbinates and swell bodies should be assessed as well, the former before and after application of a topical decongestant, to determine whether the reduction would improve nasal airflow. Patients who have previously undergone turbinate reduction and have patent nasal passages on examination but still report nasal obstruction are likely suffering from empty nose syndrome and should not undergo additional surgery to widen the nasal airway, but may benefit from augmentation of inferior turbinate volume instead.[35]

Day of Surgery

In the operating room, general anesthesia is induced, and orotracheal intubation proceeds, with the tube being taped to the midline of the lower lip to keep it out of the way and prevent it from distorting the lower third of the nose. Many surgeons and anesthesia clinicians prefer to employ a total intravenous anesthetic protocol, using propofol and remifentanil, which provide permissive hypotension to decrease bleeding and reduce coughing, agitation, and nausea on emergence.[36][37] Tranexamic acid (1 to 2 g) may be administered at the beginning, and optionally at the end of the procedure as well, to decrease intraoperative bleeding and postoperative ecchymosis and edema. Dexamethasone or another intravenous corticosteroid will help to decrease edema and postoperative nausea.[38][39][40][41] Whether or not to provide prophylactic antibiosis at the beginning of the case is a matter of some controversy, depending on whether the operation is primary or revision, and if extensive grafting is anticipated; there is a clearer consensus that postoperative antibiotics are not necessary.[42][43]

Placing the patient supine, with arms tucked tightly to the sides and the head of the bed elevated slightly will improve the surgeon's access to the nose and further decrease intraoperative bleeding. An orogastric tube may be placed at the beginning of the case and left off suction so that it can be used at the end of the operation to evacuate the stomach contents without having to be placed immediately before emergence, as the passage of the tube may be quite stimulating and contribute to a rough arousal from anesthesia. Before the injection of local anesthetic, the patient's eyes are closed and protected with tape or adhesive film dressings.

Twelve to 15 mL of local anesthetic are injected into the septum, inferior turbinates, nasal dorsum, sidewalls, tip, columella, and along the caudal margins of the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages. The medication is allowed to sit for 15 minutes for the vasoconstrictive effect to develop while the patient's face is prepped. After injection, 2 to 3 cottonoid pledgets soaked in a decongestant are placed into each nasal cavity. Male patients may require trimming of the vibrissae to facilitate the visualization needed for injection, and patients with large inferior turbinates may benefit from a decongestant spray in the holding area before arrival in the operating room.

Surgical skin preparation can be accomplished with povidone-iodine, chlorhexidine, or isopropyl alcohol, the latter of which will not obscure the subtleties of skin color and texture. The entire midface from upper lip to forehead should be exposed in the surgical field, as well as both ears, to provide access to conchal cartilage, if necessary. Revision cases may require access to the chest for costal cartilage harvest or the scalp for split calvarial bone harvest. Last, it is important to post the preoperative photographs in the operating room for reference during the case.

Technique or Treatment

Every surgeon may take a different approach to working through a rhinoplasty, and the description that follows is just 1 method. Herein, an "in-to-out and top-to-bottom" workflow is detailed. At the end of this section, see Table. Location, Deformity, and Maneuvers to Consider in Rhinoplasty, which provides a quick reference for the selection of surgical techniques to correct various nasal deformities that may be encountered.

If indicated, the turbinoplasty and reduction of the septal swell body are performed before the rhinoplasty for 2 reasons: 1) bleeding caused by the turbinoplasty will have a chance to resolve during the remainder of the operation rather than continuing through emergence and alarming both the patient and the recovery nurses, and 2) the force required to outfracture the inferior turbinates will be applied before any delicate work is performed in the rest of the nose, rather than afterward, thereby decreasing the risk of disrupting the surgical result. If the nasal septum is so deviated that it denies access to one or both of the inferior turbinates, the turbinoplasty may be deferred until after the septoplasty is complete, but the turbinoplasty should ideally not be delayed until the end of the case. Some surgeons prefer to perform the septoplasty before the rhinoplasty, electing to use a hemitransfixion incision for the septoplasty and then to approach the rhinoplasty afterward. In the workflow below, the septoplasty will be performed after the nose has been opened (if an open approach is employed) to obviate the need for the hemitransfixion incision and improve the exposure of the septum.

Modification of the septum and the dorsal hump is undertaken in the same stage of the surgery, although the order in which they are addressed will vary depending on the technique selected for reduction of the dorsal hump. Resection or rasping should be performed before the septoplasty so that the surgeon can ensure 10 to 15 mm of dorsal septal height remain after cartilage harvest/resection of deviated septal cartilage, as resecting a dorsal hump after septoplasty can result in an overly thin and weak dorsal septal strut. On the other hand, if a dorsal preservation technique is chosen, septoplasty is performed first, including resection of the septal strip that will allow the dorsum to be lowered by a push-down or a let-down maneuver. As a caveat, during revision surgery, the order of the operation may need to diverge from that described below, depending on how scar tissue affects the path of dissection and where grafting materials may have been placed previously.

Incisions and Exposure

For a discussion of the indications for selecting an approach to rhinoplasty, please see the Indications section above.

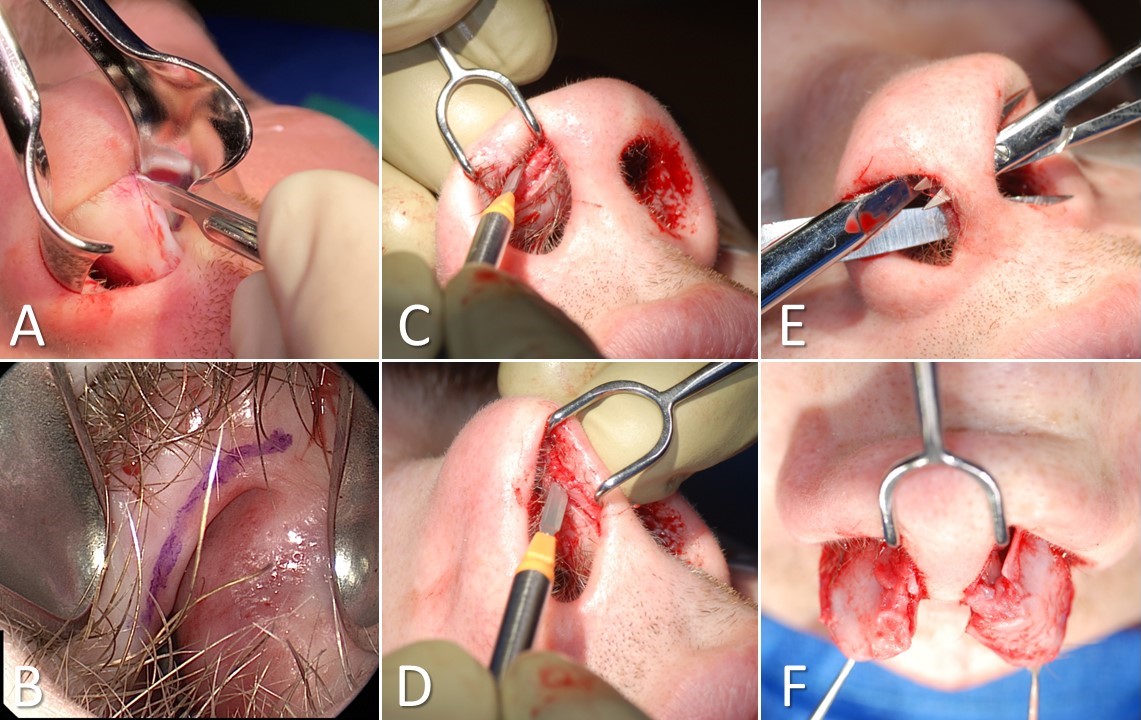

Open approach: The transcolumellar incision is marked using a stair-step or chevron shape ("inverted-V") to break up the contour of the scar and direct the contractile forces obliquely across the columella to minimize the chance of notching (see Image. Rhinoplasty Incisions). If a chevron-shaped incision is used, the chevron should be at least 3 mm in width at its base to prevent it from flattening during healing and the base should be level with the narrowest portion of the columella, which is where the skin is thinnest and least likely to produce a prominent scar. The incision itself is made with a fine blade, such as a Bard-Parker #11 or #15c, or a #6700 beaver blade, taking care to avoid damaging the underlying medial crura of the lower lateral cartilages. A columellar flap is then elevated up to the domes of the lower lateral cartilages using fine scissors (Wilmer, Converse, iris, etc.). The columellar vessels and intercrural soft tissues are isolated and divided with bipolar electrocautery, thereby exposing the medial surfaces of the medial crura. With a combination of 1 wide and 2 narrow double-pronged skin hooks, the dome of the lower lateral cartilage is flattened and held under tension while the marginal incision is made, continuing laterally from the transcolumellar incision (see Image. Open Rhinoplasty Approach). Fine scissors or a scalpel can be used for this incision. The contralateral marginal incision is then made identically. Two wide double-pronged skin hooks are then placed, one pulling upward under the SSTE and one retracting downward under the domes, so that the soft tissue can be cleared from the superficial surface of the lower and upper lateral cartilages, taking care to leave the perichondrium intact. Either scissors or cotton-tipped applicators can be used for this elevation. With the lower two-thirds of the nasal skeleton exposed, an elevator (Joseph, Cottle, or similar) is used to dissect the periosteum from the nasal bones and the frontal processes of the maxillae, thus completing the open approach.

Endonasal approach: Access is usually obtained via an intercartilaginous incision, made through the scroll region, between the cephalic border of the lateral crus of the lower lateral cartilage and the caudal border of the upper lateral cartilage (see Image. Rhinoplasty Incisions). A wide double-pronged skin hook is used to evert the nasal ala and apply downward tension to the SSTE to facilitate making the incision with a #15 blade. Scissors (eg, Joseph, Giunta, or similar) are then used to dissect blindly along the superficial surface of the upper lateral cartilages and onto the nasal bones. The perichondrium is left intact, but an elevator (eg, Joseph, Cottle, or similar) is used to dissect the periosteum from the nasal bones, and the frontal processes of the maxillae, thus completing the endonasal approach.

If a septoplasty is required, a hemitransfixion incision may be used, and it may be joined to the ipsilateral intercartilaginous incision for greater exposure. If cephalic trimming is planned, intracartilaginous incisions may be added to permit excision of the cephalic margins of the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages as well as their underlying vestibular skin (see Image. Rhinoplasty Incisions). Because the inter- and intracartilaginous incisions are located posterior to the tip of the nose, accessing the domes and medial crura of the lower lateral cartilages is challenging via the endonasal approach. If an open approach is not feasible, the tip is best accessed via a delivery approach, which is essentially a modification of the endonasal approach.

Tip-delivery approach: After the endonasal approach is complete, visualization of the lower lateral cartilages may be achieved by delivering the domes into the nasal vestibules via additional incisions. A full-thickness transfixion incision or bilateral hemitransfixion incisions are made in continuity with the medial ends of the intercartilaginous incisions. Then, marginal incisions, without a transcolumellar incision, are made parallel and anterior to the hemitransfixion and intercartilaginous incisions using a scalpel and wide double-pronged skin hook, thereby creating bipedicled (medial and lateral) chondrocutaneous flaps that contain the lower lateral cartilages. After the division of the interdomal ligaments with fine scissors, the domes can be retracted laterally into the nares (see Image. Tip-Delivery Rhinoplasty).

Septoplasty

This procedure is performed for relieving a nasal obstruction, harvesting cartilage for grafting, or correcting a dorsal or caudal nasal deviation. Septoplasty is typically performed early in the rhinoplasty. If the nose is opened, the anterior septal angle of the quadrangular cartilage is easily identified by palpation after the interdomal ligaments have been divided and the lower lateral cartilages retracted away from the midline. If the nose is not opened, a hemitransfixion incision can be used; it is placed along the side of the caudal margin of the septum, just behind the medial crus of the lower lateral cartilage. Either side can be used, with right-handed surgeons typically preferring a left-sided incision for ergonomic reasons, but bilateral septal flaps can be elevated via a single hemitransfixion incision.

Once the septal cartilage is visualized, fine scissors are used to snip down to the level of the perichondrium, which is then gently cross-hatched with a #15 blade scalpel to expose the bare cartilage. An elevator, such as a Woodson or a Cottle, can then be used to develop a plane between the cartilage and the perichondrium. Elevation in this plane then continues superiorly onto the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone, posteriorly onto the vomer, and inferiorly over the maxillary crest and onto the nasal floor (see Image. Internal Nasal Anatomy). Passing from the quadrangular cartilage onto these bony structures necessitates a transition to a subperiosteal plane, which is not typically challenging except for along the maxillary crest. Maintaining the dissection within the correct plane is important for 2 reasons: the plane is avascular and therefore likely to result in less bleeding, and keeping the perichondrium or periosteum attached to the mucosa makes the flap stronger and therefore more resistant to tears and subsequent septal perforation.

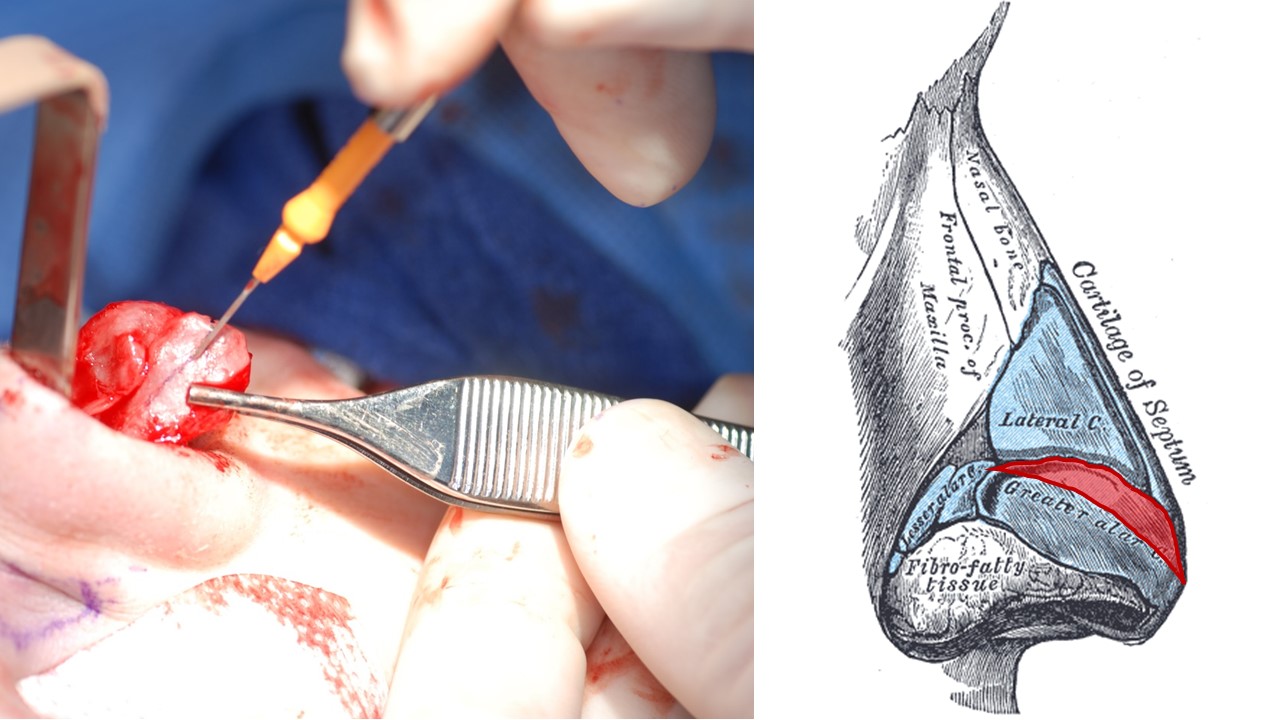

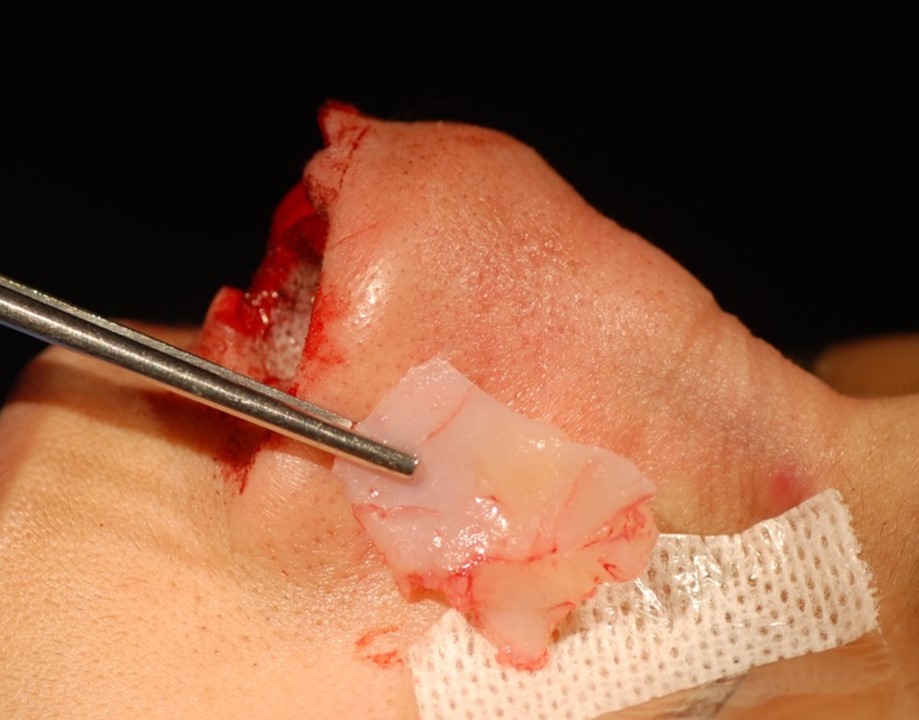

If the septoplasty is performed via an open rhinoplasty approach, disarticulating the upper lateral cartilages from the dorsal septum early in the process will substantially improve visualization and make room for later spreader graft placement. Once the septal flaps are elevated bilaterally, the deviated bone and cartilage are resected, or straight cartilage is harvested as necessary. The cartilage is often incised with a Freer septal knife, a #15 blade, or a Ballenger swivel knife, while bony cuts are typically made with Gorney double-action nasal shears, Jansen-Middleton rongeurs, and osteotomes (see Image. Septal Cartilage Harvest). It is critical to leave at least 10 to 15 mm of cartilage intact along the dorsal and caudal aspects of the septum (the "L-strut") to provide enough support to the nose to prevent a postoperative saddle deformity. Critical to this is maintaining the integrity of the bony-cartilaginous junction at the keystone, although the bony-cartilaginous junction at the anterior nasal spine is also important for tip support. If the L-strut itself is deviated, grafting techniques may be required to straighten it, and these are often more easily employed via an open rhinoplasty approach. For a more in-depth discussion of septoplasty, please see the following article: Septoplasty.

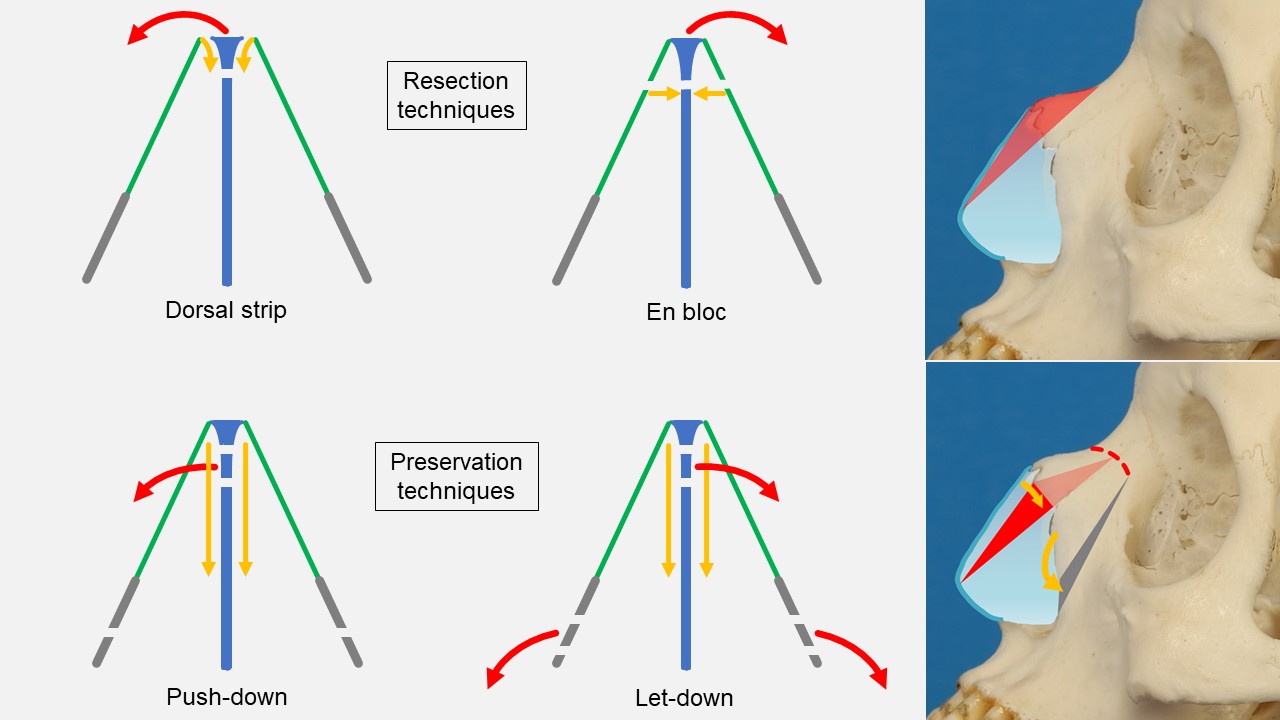

Dorsal Hump Reduction

Resection: Reduction of a dorsal hump by resection can be accomplished using a rasp, an osteotome, a piezotome, a scalpel, and/or dorsal scissors, depending on the size of the hump, its location, and the surgeon's instrument preference. Given that most dorsal humps are roughly centered over the rhinion and therefore have both cartilaginous and bony components, some combination of sharp excision of cartilage and rasping or osteotomy of the bone is usually required. The cartilage is most frequently addressed with a scalpel, such as a #11 blade, which is used to cut the anterior septal angle to the rhinion, removing a wedge of cartilage that is thickest superiorly; the thickness at this point corresponds to the desired amount of dorsal hump reduction.

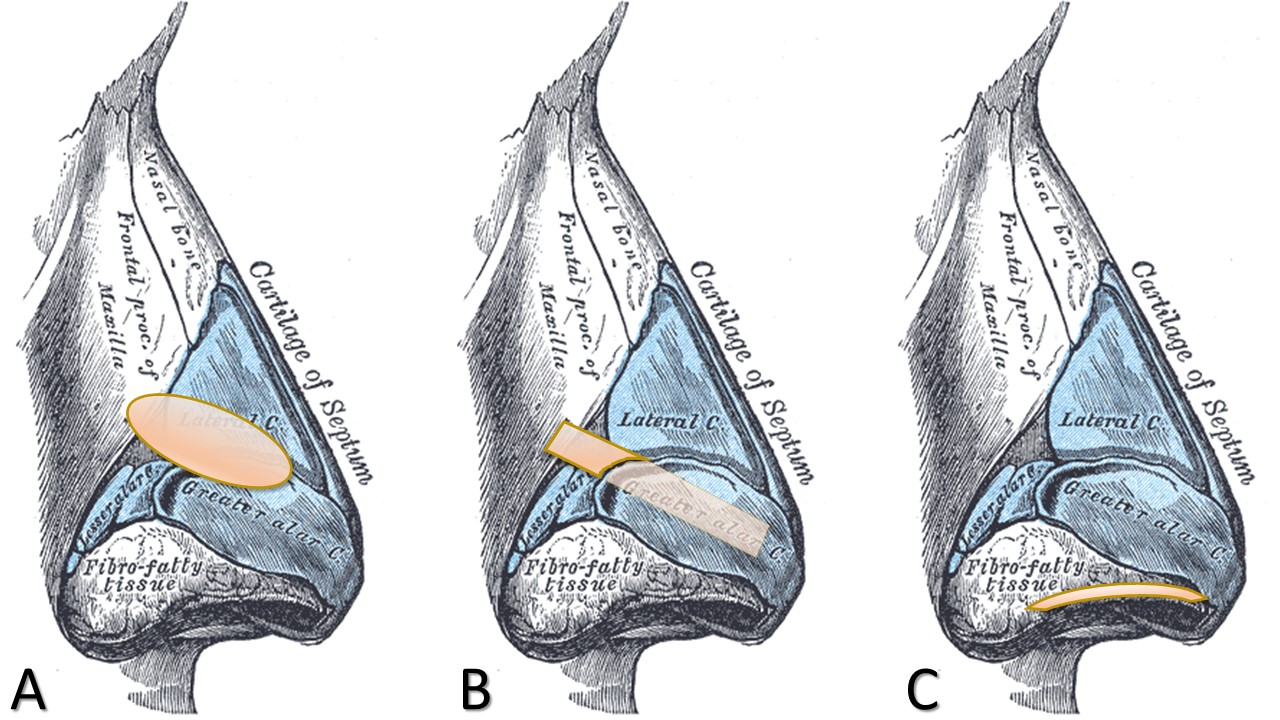

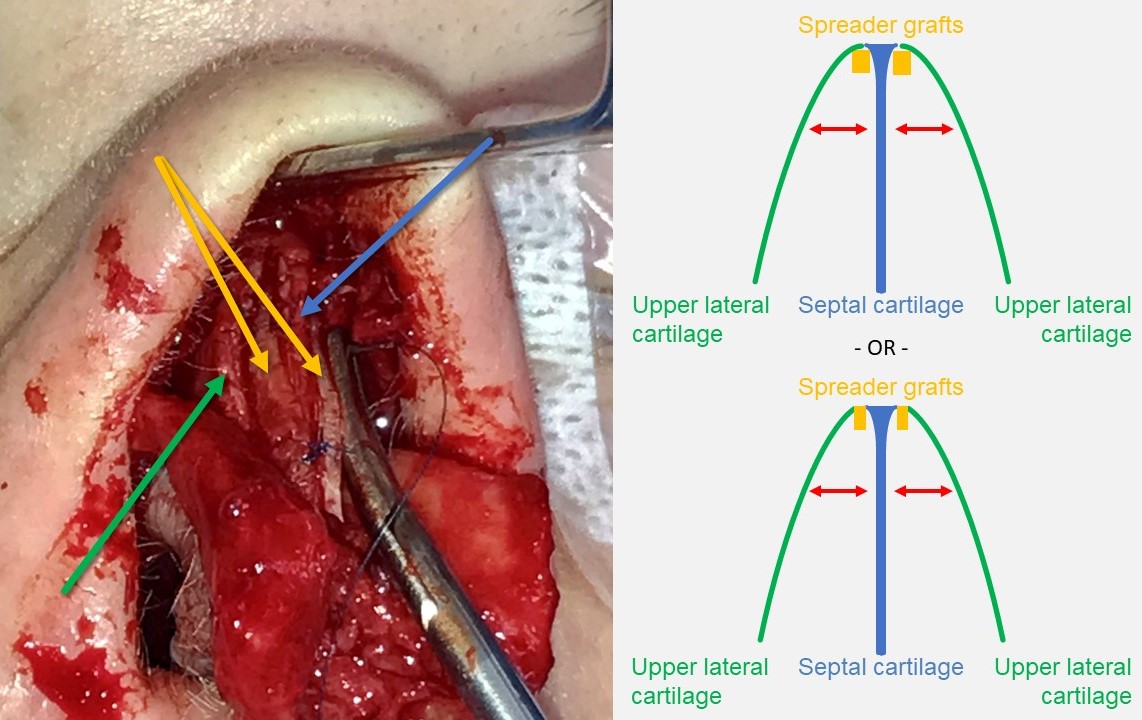

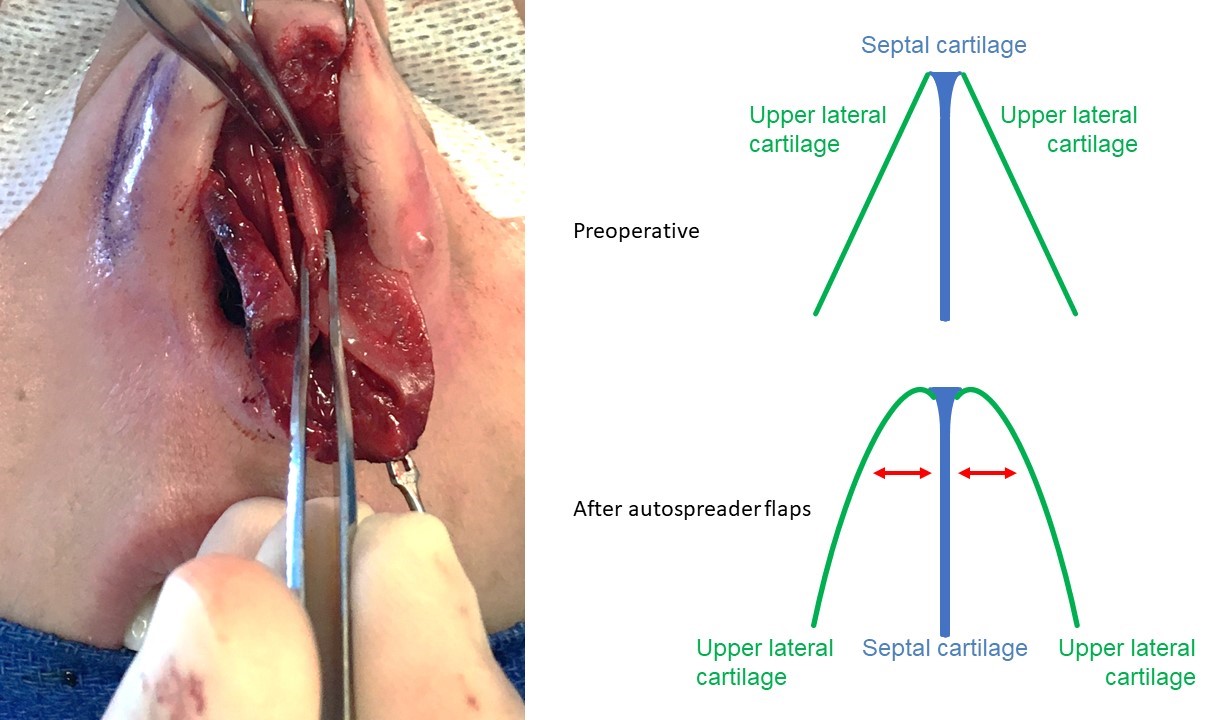

Resecting cartilage to the anterior septal angle leaves a smooth dorsum, whereas a shorter resection may contribute to a polly beak deformity. While it is better to remove too little cartilage and then, if necessary, return to resect more, than it is to take too much at the beginning, it is preferable to remove the correct amount initially so that the cartilage has the greatest potential use as a graft, which is difficult to do if the cartilage is shaved in multiple iterations. Cartilage resection may precede disarticulation of the upper lateral cartilages from the dorsal septum (en bloc resection) or it may come after (dorsal strip resection) if the plan involves autospreader flaps to open the internal nasal valve, which are best employed when there is a relative excess of upper lateral cartilage height compared to the dorsal septum (see Image. Dorsal Hump Reduction).

Reduction of humps with small bony components can then be completed with a rasp or piezotome, while larger humps may require resection of the bony component with an osteotome. If an osteotome is used, or even if aggressive rasping is performed, an open roof is likely to result, and this will need to be closed with lateral osteotomies to prevent an open roof deformity of the upper vault. While the goal of dorsal hump reduction is often to create a flat nasal dorsum, it is important to maintain a subtle dorsal hump of the nasal skeleton itself because the SSTE is thinnest over the rhinion and a truly flat nasal dorsal skeleton may cause a pseudo-saddle deformity once the SSTE is redraped over it.

Dorsal preservation: Cottle is credited with describing hump reduction with a dorsal preservation technique, a technique that permits lowering of the nasal dorsum without disarticulating the upper lateral cartilages from the quadrangular cartilage or causing an open roof deformity; in essence, leaving the upper and middle vaults of the nose intact. There are 2 primary dorsal preservation techniques: "push-down" and "let-down." Both of these involve removing a strip of septal cartilage and bone below the dorsum that corresponds in height to the desired degree of dorsal deprojection. This can be accomplished via a hemitransfixion incision or an open rhinoplasty approach, bearing in mind that the upper lateral cartilage should not be disarticulated from the quadrangular cartilage before beginning the septoplasty.

Lateral and transverse osteotomies are then made, which mobilize the bony vault and allow the dorsum to be "pushed down" into its desired position. For larger humps, bilateral intermediate osteotomies made medial to the lateral osteotomies allow resection of slim wedges of bone that then permit even greater descent of the dorsum (see Image. Dorsal Hump Reduction). The osteotomies used for dorsal preservation techniques must be made very precisely, and many surgeons prefer to use a piezotome for this reason. The piezotome, however, is rather bulky and requires substantially more elevation of the maxillary periosteum for access, which may contribute to more postoperative edema than is seen after the use of osteotomes.

Modification of the Bony Vault

Narrowing the bony vault: For adjusting the width of the upper third of the nose, medial and lateral osteotomies are typically performed bilaterally, with the lateral osteotomies taking a high-low-high configuration (see Image. Nasal Osteotomies for Adjusting the Width of the Bony Vault). Most of the lateral osteotomy (the "low" portion) is placed in the nasofacial junction to avoid a visible or palpable step-off. The superior extent of the lateral osteotomy is the nasofrontal suture, to prevent a rocker deformity. The inferior extent is angled to leave a "Webster's triangle" of bone intact at the piriform rim, which keeps lateral alar ligamentous attachments intact for support of the external nasal valve.[44]

As with dorsal preservation techniques, a piezotome may be substituted for the osteotomes. The medial osteotomies are usually made either through intercartilaginous incisions (via an endonasal approach) or via an open rhinoplasty approach. Curved, guarded Anderson-Neivert osteotomes are used most commonly for medial osteotomies, engaging the nasal bones in a paramedian position, between the upper lateral cartilage and dorsal septum, at the edge of the nasal bone. The osteotomy is made continuously, starting superiorly but then rapidly beginning to fade laterally, where it will come close to, but not meet, the superior aspect of the lateral osteotomy.

The reason the medial and lateral osteotomies are kept separate is that a greenstick fracture can then be produced between the 2 osteotomies, which will allow the intervening bone segment to move but still provide it some stability. The nasal bones are comparatively thin and do not require much force to cut, in contrast to the frontal processes of the maxillae, which do require substantial effort to complete the lateral osteotomies. Lateral osteotomies may be made either percutaneously in a "postage stamp" perforation fashion with a small (2-3 mm) straight osteotome, or they may be made via small incisions across the mucosa at the piriform rim, at the level of the junction of the inferior turbinate and the lateral nasal wall. The latter technique usually employs an Anderson-Neivert osteotome after the periosteum has been elevated.

When using Anderson-Neivert osteotomes, it is important to remember that the side-mounted guard will be palpable under the SSTE several millimeters ahead of the cutting edge of the instrument, and this should be taken into account when assessing the progress of the osteotomy. The use of percutaneous postage-stamp osteotomies tends to leave the bony segments more stable than continuous intranasal osteotomies because of the jagged edge of the osteotomy; however, that may also make moving the osteotomized bone segments more challenging. Bones tend to be easier to mobilize after continuous osteotomies, even with some periosteum preserved for stability.

Percutaneous osteotomies have the further disadvantage that the percutaneous entry points may produce visible, albeit small, scars in some patients, particularly those with darker skin. If there are any rough contours after the osteotomies, rasping may be performed to smooth the bone, but rasping mobile bony segments is challenging. Ideally, all rasping should be complete before beginning the osteotomies. If an overly mobile "flail" segment of bone is encountered after the osteotomies are complete, packing the nasal cavity with iodine-impregnated gauze or placing transnasal k-wires will usually provide enough support to keep the bone in the desired position during the early healing process.

Straightening the bony vault: For noses with a deviation in the upper third area, bilateral lateral osteotomies and a transverse nasal root osteotomy will mobilize the bony vault as a unit and permit it to be reoriented. In these cases, the lateral osteotomies typically take a high-to-low configuration and are connected directly with the root osteotomy at the level of the nasofrontal suture to facilitate movement, rather than making a deliberate greenstick fracture (see Image. Nasal Osteotomies for Shifting a Deviated Bony Vault). The root osteotomy is most easily accomplished percutaneously with a 2 to 3-mm straight osteotome placed through a horizontal stab incision at the nasion because it is made very high on the nose.

For severely deviated bony vaults (≥3 mm deflection of the rhinion lateral to the facial midline), an intermediate osteotomy is often required on the side contralateral to the direction of deviation. The intermediate osteotomy produces a slim wedge of bone that telescopes down into the nose and opens a gap into which the bony vault can shift on its way back to midline, similar to the osteotomies used in the let-down dorsal preservation technique. To avoid unintended fractures of the bony pyramid, the use of a Sayre or Boies elevator to raise and shift the vault gently is more effective than attempting to move it with laterally-directed force applied with the surgeon's thumbs. Occasionally, despite mobilizing the bony vault on the left, right, and top, it remains unable to move freely; in these cases, a dorsal septotomy (typically using a pair of scissors to cut the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid) may be required to complete mobilization.

Special situations: When the bony vault is deviated as well as being excessively wide, 2 options exist for planning the osteotomies: 1) medial osteotomies can be added to the lateral, root, and intermediate osteotomies to narrow the vault while repositioning it, or 2) unilateral medial and lateral osteotomies can be made on the side towards which the upper vault has deviated so that that side of the bony vault can be shifted towards the midline, thus straightening and narrowing the upper third. The first option adds to the complexity of the osteotomies and increases the risk that a flail segment or misdirected osteotomy will occur. The second option is only applicable if the nasal bones are not severely deviated, as unilateral medialization in those cases will result in excessive narrowing of the upper third of the nose.

If there is a dorsal hump and a deviated upper vault, a dorsal preservation technique can be used with unilateral let-down osteotomies on the side opposite the direction of deviation. This requires the finesse and precision necessary to employ dorsal preservation techniques but is very reliable when performed correctly. Alternatively, the hump can be resected as described above and the open roof closed asymmetrically to correct the deviation. For noses with complex contours in the upper vault, frequently due to blunt facial trauma or, rarely, multiple prior rhinoplasties, osteotomies through the prior fractures may be the best option to restore a normal shape to the nose; this is a technically challenging procedure that may be more effectively accomplished using computed tomography guidance.[45]

Management of the Midvault

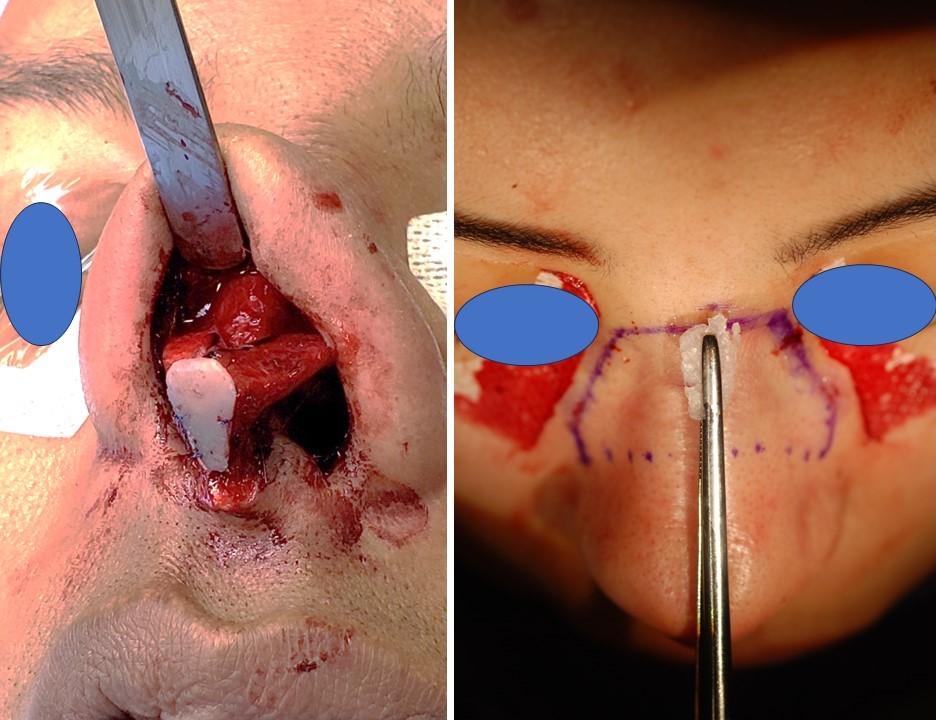

Supporting the internal nasal valve: Patients with congenitally narrow internal valves or acquired narrowing due to trauma or prior rhinoplasty will benefit from spreader grafting, which will open the internal valve angle and correct contour abnormalities, such as an inverted V deformity. While spreader grafting is frequently performed bilaterally, if the valve dysfunction is unilateral or there is a visible concavity on only 1 side of the midvault, only 1 graft may be needed. On the other hand, for patients with a desire to maintain a narrow dorsum for aesthetic reasons, placement of spreader grafts should be considered very carefully, as they can widen the midvault visibly if the SSTE is not thick. The spreader grafts described by Sheen in 1984, also known as "vertical" spreader grafts, were originally placed endonasally into tight tunnels created between the perichondrium and the quadrangular cartilage, just beneath the junction of the upper lateral cartilages and the dorsal septum.[6]

This maneuver had the effect of eliminating the inverted-V appearance while improving nasal airflow. Using this technique, the tunnels must be placed very precisely to ensure that the grafts do not migrate away from the desired location; mattress sutures across the septum using a 4-0 chromic gut may be passed underneath the grafts to help maintain their positioning. Vertical spreader grafts are also commonly placed via open rhinoplasty, which permits better visualization and verification of correct graft placement. The grafts are ideally made from straight segments of harvested septal cartilage, measuring 1 to 2 mm in width, 3 to 4 mm in height, and having a length just longer than the length of the medial margin of the upper lateral cartilage, so that the graft can run the length of the entire junction between the upper lateral cartilage and the septum and underlap the nasal bones slightly (typically 17-20 mm in total).

Vertical spreader graft placement via an open rhinoplasty approach is typically performed in 1 of 2 ways. After disarticulation of the upper lateral cartilage from the quadrangular cartilage, either 1) the graft itself is placed directly between the medial edge of the upper lateral cartilage and the dorsal septum, or 2) the graft is placed just below the junction to wedge the upper lateral cartilage outwards without widening the dorsum as much as option 1, but potentially providing less width to the internal valve as well (see Image. Spreader Grafting). Either permanent 5-0 or 6-0 polypropylene or resorbable 5-0 polydioxanone suture can be used to fixate the grafts and resuspend the upper lateral cartilages, bearing in mind that if permanent sutures are used, it is best to avoid leaving the knot on the dorsum, where it will be most palpable.

If appropriate septal cartilage is unavailable to fashion the spreader grafts, suitable cartilage may be harvested from the auricle or the rib. Auricular cartilage is brittle and flimsy, however, and costal cartilage is prone to warping unless cut obliquely (see Image. Costal Cartilage Grafting).[46] To reduce the chance of a costal cartilage graft warping after placement in the nose, carving the graft and then letting it rest in normal saline for at least 15 minutes should indicate whether or not it will remain straight. Costal cartilage has a concentric lamellar structure, and the inclusion of as many of these layers as possible in the graft will reduce the chance of warping. Costal cartilage may be harvested from the patient or obtained as an irradiated or fresh frozen cadaveric graft. Proponents of both options are outspoken, with critics of cadaveric cartilage use arguing that it is more likely to resorb, while its supporters disagree and point out the risk of pneumothorax and increased pain associated with autologous costal cartilage harvest.[47][48][49]

Alternatively, autospreader flaps may be used instead of vertical spreader grafts if there is an excess of upper lateral cartilage width relative to septal height, as occurs after the reduction of a dorsal hump using a dorsal strip resection. To use autospreader flaps, the mucoperichondrium is first elevated laterally away from the medial margin of the upper lateral cartilages to prevent mucosa from becoming trapped. The upper lateral cartilage is then scored gently on its superficial surface, 2 to 3 mm lateral and parallel to its medial margin to facilitate folding the medial margin inwards. Once the medial margin of the upper lateral cartilage is folded inwards, the cartilage can be sutured to the dorsal septum as described for spreader grafts, thus flaring the upper lateral cartilage laterally and opening the internal nasal valve (see Image. Autospreader Flaps).

Using a dorsal preservation technique for hump reduction will have a similar effect, as the descent of the dorsum will force the upper lateral cartilages outwards. For severely narrowed middle vaults, the horizontal spreader graft, or "butterfly" graft, is also an option. This graft is made from a slightly curved, or even flat, piece of cartilage that is shaped like an oval or a rounded hourglass and placed across the lower midvault, then sutured to the upper lateral cartilages so that it pulls them outward and aggressively opens the internal valve. This graft is often visible beneath the SSTE, and therefore should only be used after appropriate counseling and only for patients for whom nasal breathing is the uncontested top priority.

On the other hand, for mild internal nasal valve collapse, "flaring" sutures may be used instead of grafting. These are horizontal mattress sutures placed from one upper lateral cartilage across the dorsum and into the other, with the suture passing through the upper lateral cartilages running on the deep surface of the cartilage (but not through the mucosa) and parallel to the nasal septum, 2 to 4 mm lateral to the midline. The farther from the midline the sutures are placed, the more flaring of the upper lateral cartilages will occur, opening the internal nasal valves without substantially widening the dorsum. Permanent sutures, such as 5-0 polypropylene, are usually used for this maneuver.

Addressing lateral deviation and contour asymmetry: In the case of the C-shaped nose, or for patients with unilateral midvault narrowing, a unilateral spreader graft on the concave side may be placed. Alternatively, if there is bilateral internal nasal valve obstruction, bilateral spreader grafts can be used, with the graft on the concave side being thicker. Spreader grafts, when made slightly taller (5-6 mm in height) can also be used as septal batten grafts to help straighten the dorsal septal L-strut, which is particularly useful for straightening C-shaped noses. In these cases, if the dorsal septal deviation extends to the anterior septal angle, beyond the caudal margin of the upper lateral cartilage, the spreader graft can be made longer: an "extended" spreader graft.

The caveat to this is that widening the anterior septal angle will result in widening of the supratip area, which is often aesthetically unappealing. For noses that are deviated to one side, rather than having a C-shaped curvature, "clocking" sutures are an effective option to straighten the midvault, with or without spreader graft placement. Clocking sutures are obliquely oriented horizontal mattress sutures used to resuspend the disarticulated upper lateral cartilages to the dorsal septum (and to secure the spreader grafts, if present). They are angled such that the pass through the upper lateral cartilage on the side towards which the nose is deviated is made more caudally than the contralateral pass.

When the suture is tightened, it will cause the upper lateral cartilages and spreader grafts to slide relative to one another and shift the midvault back towards the midline. Overtightening of these sutures will leave a palpable divot in the upper lateral cartilage; however, it is better to place several looser sutures than a single tight one. Unlike flaring sutures, clocking horizontal mattress sutures are thrown so that the deep passes are through the septum, rather than under the upper lateral cartilages.

Correcting a saddle deformity: Mild saddle deformities with predominantly aesthetic effects and negligible resultant nasal obstruction may be corrected with onlay grafting, which is both easy and effective. Crushed septal cartilage is a popular choice, and this can either be inserted into a tight pocket under the SSTE (in endonasal rhinoplasty), or secured with sutures or fibrin glue (in open rhinoplasty). If septal cartilage is not available, auricular or costal cartilage may be used, although they do not crush well and typically need to be diced. Because dicing does not produce as fine a particle as crushing, placement of a fascial graft (temporalis or temporoparietal) under the SSTE will help prevent palpable or visible diced cartilage contours. More severe saddle deformities will affect the nasal airway by causing collapse of the internal nasal valves; these cases require more aggressive treatment.

One option is to rebuild the septum from the bottom up by performing extracorporeal septal reconstruction. This entails using either the available septal cartilage or costal cartilage to fashion an L-strut using 1 or 2 extended spreader grafts and a caudal strut graft. The upper lateral cartilages can then be attached to the construct, thus reopening the internal valves. Some surgeons prefer a "top-down" approach, in which the dorsum is reconstructed with a rigid graft, and the middle vault is suspended from it. A classic example of this is the placement of a split calvarial bone graft into a tight pocket made via an intercartilaginous incision (see Image. Additional Rhinoplasty Grafting Materials). If the nasal bones are rasped to create a raw surface, the graft will usually heal in place without fixation using hardware, although plate and screw fixation is also an option when the graft is placed via an open approach. Rib is a popular grafting material, as well, because it contains both bony and cartilaginous components, and therefore mimics the natural nasal structure more closely than a bone-only calvarial graft.[50]

Management of the Lower Third

Modifying the supratip: A common presenting complaint is a "bulbous" nasal tip, which is frequently a result of excessive width and/or curvature of the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages. The classic maneuver to address this problem is cephalic trimming, in which bilateral strips of cartilage along the superior aspects of the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages are excised (see Image. Cephalic Trimming). Removing these strips reduces the prominence of the supratip region and also disarticulates the lower lateral cartilages from the upper lateral cartilages.

While the scroll region is technically one of the major tip support mechanisms, the removal of cartilage in this area and resultant soft tissue contraction during the healing process typically results in some upward rotation of the tip over time. When performing a cephalic trim, leaving 7 to 8 mm of lateral crural height intact to prevent alar retraction is known as a "complete strip" technique, referring to the remaining cartilage of the lateral crura. If a wedge of cartilage is removed from the lateral crura in addition to the cephalic trim, the technique is known as an "incomplete strip," which is used to augment the upward rotation of the nasal tip, albeit at the expense of structural stability.

Cephalic trimming can be performed endonasally, using a combination of inter- and intracartilaginous incisions, which results in the removal of the cephalic cartilage strip and its underlying skin. The maneuver may also be performed via the tip-delivery and open approaches without removing additional soft tissue from the cartilage. Similar to the cephalic trim is the cephalic turn-in maneuver, in which the cephalic aspects of the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages are folded medially and sutured behind the lateral crura rather than being excised. Doing this narrows the supratip region, like the cephalic trim, but it also helps to straighten out any irregular curves of the lateral crura and provides additional rigidity to reduce dynamic collapse during inspiration. Performing a cephalic turn-in involves making a cartilage incision in the same location as that used for cephalic trimming with a complete strip, but the incision is only partial thickness to facilitate a precise fold.

The vestibular skin is then elevated off the undersurface of the lateral crus to make a pocket that will fit the folded cartilage. Finally, the cartilage is folded and sutured in place, through the vestibular skin and 2 layers of cartilage, with the knot left in the naris; a 5-0 chromic gut suture works well. For noses with overly narrow supratip regions, often due to prior rhinoplasty, placement of a lateral crural spanning graft across the anterior septal angle will help to lateralize the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages, thus providing more supratip width and improving the nasal airway. These grafts are trapezoidal and laid flat, transversely atop the quadrangular cartilage, with the wider side of the trapezoid in the cephalic position and the narrow side just behind the nasal tip.

The oblique sides of the trapezoid then push outwards on the lateral crura. Securing this graft very precisely with permanent sutures is critical, as any tilt will cause visible asymmetry in the nasal tip. Lastly, excessive projection of the supratip may be due to a tall anterior septal angle, whether congenital (a "low" hump) or iatrogenic (a polly beak deformity). Removal of a strip of dorsal quadrangular cartilage is a simple remedy for this problem unless the etiology is a scar under the SSTE, in which case, triamcinolone injections or careful surgical debridement will be more effective. Caution should be used when shaving down the anterior septal angle for the same reason that a dorsal hump should be resected before performing a septoplasty; ensuring that an adequate L-strut remains after cartilage removal is critical.