Introduction

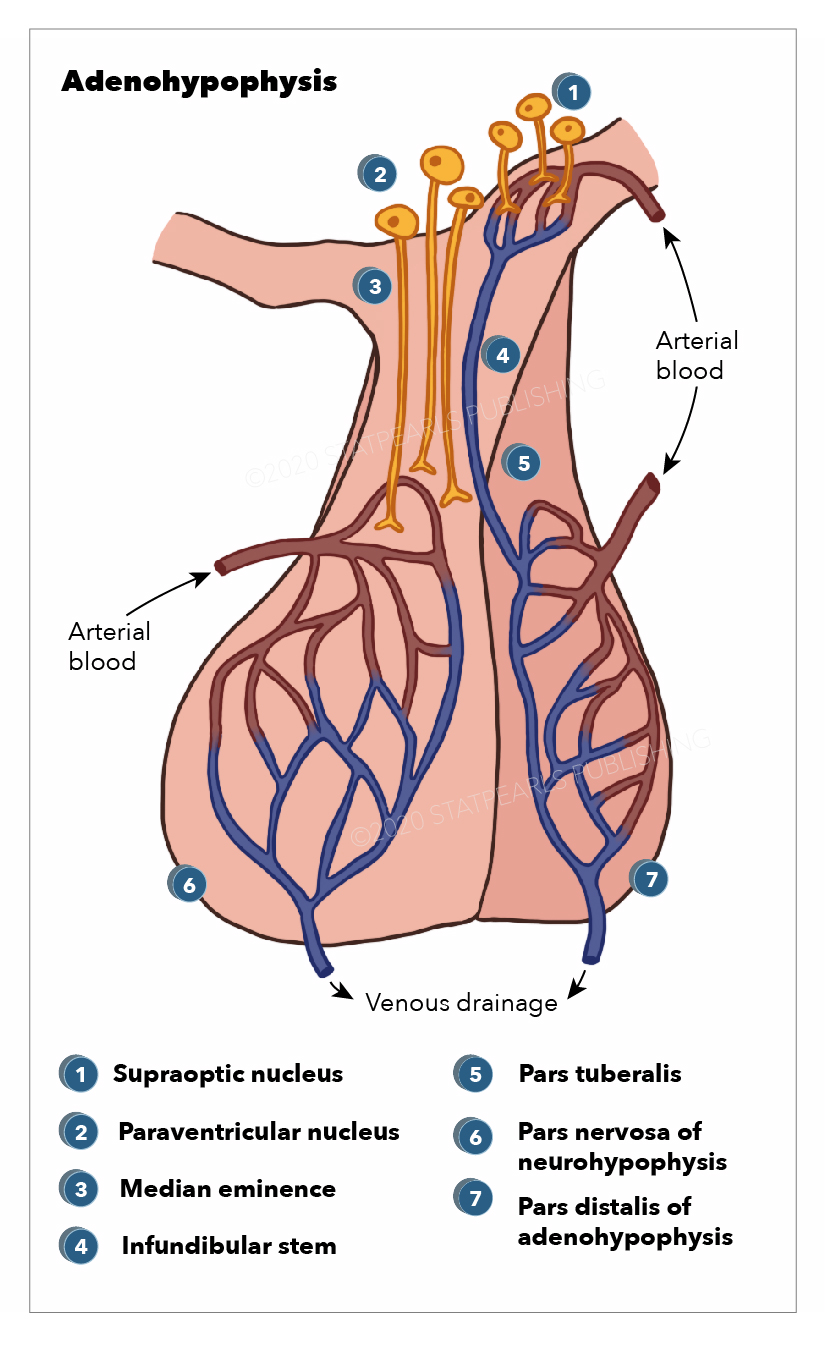

The neurohypophysis (pars posterior) is a structure that is located at the base of the brain and is the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland. Its embryological origin is from the neuroectodermal layer called the infundibulum. The neurohypophysis is divided into two regions; the pars nervosa and the infundibular stalk. Sometimes the pars intermedia and the median eminence are included. It secretes oxytocin and vasopressin; vasopressin is also called antidiuretic hormone (ADH) due to its function of preventing diuresis. These hormones are produced at the magnocellular neurosecretory cells in the hypothalamus, specifically, from the paraventricular nuclei and supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus. These cells are neurons that project axons to the neurohypophysis. The hormones are transported from the hypothalamus to the neurohypophysis where they are stored and later released into the neurohypophyseal capillaries, which then carry the hormones into the systemic circulation.[1]

Dysfunction of the posterior pituitary affects the hormonal homeostasis, which causes diabetes insipidus (DI), and the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) secretion. Disorders caused by oxytocin deficiency are rare, but most are related to pregnancy and lactation problems.

The posterior pituitary contains pituicytes that function in the pars nervosa like glial cells for support and modulation of the release of the hormones. A tumor formed from the pituicytes is called pituicytoma.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Several causes can produce neurohypophysis dysfunction.

Tumors

- Pituitary adenoma

- Hypothalamic glioma

- Craniopharyngioma

- Pituicytoma

- Granular cell tumors

- Germ cell tumors

Traumatic brain injury (TBI)

Brain surgery

Metabolic

Inflammatory

- Sarcoidosis

- Multiple sclerosis

- Pituitary hypophysitis

Infectious

- Meningitis

- Encephalitis

- Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- Abscess

- Septic shock

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

Hypoxia

- Sheehan syndrome

- Pituitary apoplexy

- Cardiac arrest

Hydrocephalus

Anorexia

Aneurysm (anterior communicating artery)

Congenital

- Pituitary stalk interruption syndrome

Genetic

- Prader–Willi syndrome

- Multiple endocrine neoplasia-1

Medications

- Phenothyazydes

- Carbamazepine

- Valproic acid

- Omeprazole

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

- Morphine

- Ecstasy drug (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine)

- Vincristine

- Amitriptyline

Epidemiology

Disorders of the neurohypophysis have variable etiologies that affect different populations from a young age until late adulthood; the etiology influences the frequency of the condition. The prevalence of hypopituitarism is 29 to 45 per 100,000, with an incidence of 4.2 new cases per 100,000 per person per year with no gender predominance.[2] The majority of the studies evaluate the dysfunction of the entire pituitary gland.

In central DI, the reported incidence after traumatic brain injury (TBI) is between 3 to 50%. Its frequency varies widely as the parameter established by each study for diagnosing DI might underestimate its actual incidence. Hyponatremia affects 15% of hospitalized patients. The SIADH secretion causing hyponatremia has been reported as the most common abnormality following a TBI in children and adults.[3] SIADH secretion is responsible for 46% of the cases of hyponatremia, which is the most common electrolyte abnormality. For some neurological conditions, the presentation of SIADH secretion is more than 70%. In neurosurgical units, there is a 5 to 10% prevalence of SIADH secretion due to disorders of the posterior neurohypophysis.[4]

The neurohypophysis is a popular site for germinomas, which are most commonly found in the pineal region. Presentation at the neurohypophyseal/pineal area is common with germinomas. Half of the patients with a combined tumor at the pineal and pituitary gland are germinomas.[5]

Pituitary stalk interruption syndrome presents with a triad that consists of the ectopic posterior pituitary, thin or absent pituitary stalk, and anterior pituitary hypoplasia. Central DI occurs in up to 10% of cases. It is more prevalent in males (2:1). In patients with hypopituitarism, it can be the etiology in 4-8% of the cases.[6][7][8][9][10][11]

Granular cell tumors are the most common lesions to arise primarily in the neurohypophysis and have been discovered in 9% of routine neurohypophysis autopsy specimens.[12][13] They are considered to be unique neoplasms of the neurohypophysis and pituitary stalk; they have been suggested to derive from pituicytes. They occur more frequently in women than in men (2 to 1).[14][15] Granular cell tumors comprise 0.17 % of resected sellar lesions in major transsphenoidal series.[16]

Sheehan syndrome is more prevalent in developing countries and is estimated to occur in approximately 3.1% of parous women, more common with home delivery.[17] Sheehan syndrome causes 6-8% of all causes of hypopituitarism.[17]

Pathophysiology

The neurohypophysis secretes two neurohormones, oxytocin, which increases uterine contractions, and vasopressin, which increases the reabsorption of water by the distal tubules of the kidney. These hormones are packed in secretory vesicles and granules at the magnocellular neurosecretory cells in the hypothalamus. They are released from the paraventricular nuclei and supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus, where they travel down to the neurohypophysis by the axons of the magnocellular cells which project from the hypothalamus to the neurohypophysis.[18]

The hormones are then stored at the herring bodies of the neurohypophysis, which are the terminal end of the axons. For their release from the herring bodies, action potentials are produced, which activates voltage-gated channels allowing calcium to enter and trigger the release of the hormone into the neurohypophyseal capillaries, which then transport the hormones into the systemic circulation. Predominantly, the paraventricular nucleus is related to oxytocin secretion, while the supraoptic nucleus is concerned with vasopressin secretion. Small amounts of each hormone are also produced at the other nuclei. The release of these hormones is triggered in response to afferent stimuli coming from outside neurons projecting to the magnocellular neurons of the hypothalamus.

The neurohypophysis receives its blood supply from the inferior hypophyseal artery, which is a branch from the cavernous internal carotid (ICA) artery. The cavernous ICA has a dorsal trunk called the meningohypophyseal trunk, which gives three terminal branches; inferior hypophyseal artery, tentorial artery (artery of Bernasconi and Cassinari), and dorsal meningeal artery. Venous drainage of the posterior pituitary gland is by the short portal and hypophyseal veins into the cavernous sinus.[17]

Sheehan syndrome can develop DI and hypernatremia due to ischemic necrosis damage to the posterior gland causing impaired vasopressin secretion. Hyponatremia can also occur due to an increased ADH secretion as a response to hypotension and reduced cardiac output owing to glucocorticoid deficiency. Also, the cortisol deficit stimulated the secretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone, which further stimulates the ADH secretion.[17]

During septic shock, vasopressin secretion undergoes a biphasic pattern. Initially, there is an increased secretion to maintain homeostasis, but later, when hypotension is pronounced, there is an unexpected significant decrease in the secretion. This decrease is thought to occur due to depletion of the vasopressin stores in the neurohypophysis, from autonomic dysfunction, and from nitric oxide inhibition of secretion at the hypothalamus.[19]

In TBI, DI is caused by direct damage to the neurohypophysis, pituitary stalk, hypothalamic nuclei, the vascular supply, traumatic edema in the neurohypophysis, or hypothalamus. These changes are usually reversible, but irreversible changes with gliosis can cause permanent DI.[20][21]

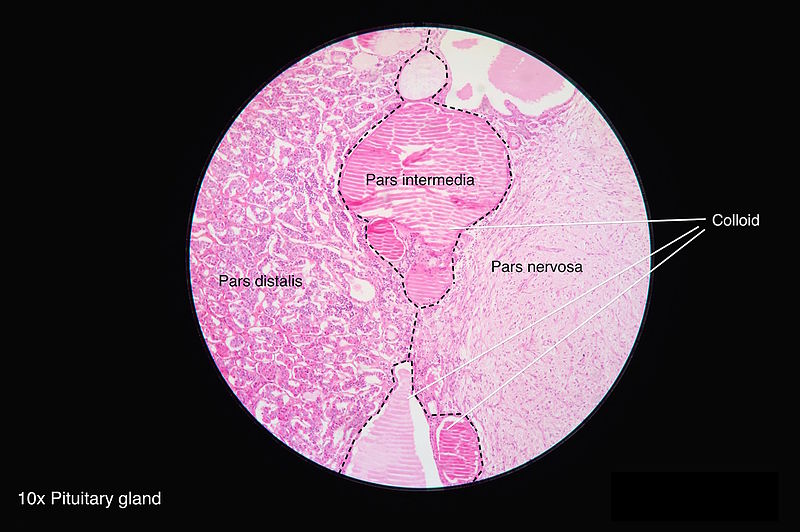

Histopathology

The neurohypophysis is made of the axons arising predominantly from magnocellular neurons of the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus. They form the hypothalamohypophyseal tract and these axons terminate near the sinusoids of the posterior lobe. The neurosecretory granules mostly contain oxytocin or vasopressin. The axon terminals are supported by pituicytes, which express the Thyroid transcription factor (TTF)-1 and demonstrate only patchy GFAP and S100 expression.[22]

History and Physical

Past medical history and previous medication use should be noted. It is essential to assess the recent medical history for depression, psychosis, seizures, or cancer because some antidepressants, anticonvulsants, antipsychotic agents, and cytotoxic agents can cause SIADH secretion. For those unconscious patients, questioning how the patient was immediately before the episode is essential. The most common presentation in SIADH secretion will be hyponatremia with a euvolemic fluid status in which clinical features include normal blood pressure, regular heart rate, normal skin turgor, moist mucus membranes, absent jugular venous pulsations, no pitting edema, and normal central venous pressure if measured. Clinical manifestations include nausea, vomiting, restlessness, headache, lethargy, obtundation, seizures, coma, and respiratory arrest. These manifestations progress as the level of hyponatremia advance from mild to severe.

In a presentation of DI due to neurohypophysis dysfunction, it is essential to rule out all other acquired etiologies of DI as the treatment should address the primary etiology causing the symptoms. The most common symptoms of DI include polyuria and polydipsia, with the patients complaining of increased thirst that at first can be controlled by increasing the water intake to maintain normal levels of serum osmolality and volume status. Some patients with altered neurological status will not recognize the thirst sensation and will not be able to drink water developing free water deficiency with hyperosmolarity, hypernatremia, and signs of dehydration that can progress to hypertonic encephalopathy with irritability, confusion, disorientation, muscle twitching, seizures, coma, and death. Other symptoms include weakness, fatigue, and myalgias.

Some patients may develop acute kidney failure, hypotension, muscle damage, and even hepatic failure. There is an increased incidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage, strokes, and deep vein thrombosis in the setting of hyperosmolar states.[23] Adipsic DI is a condition that is crucial to recognize because patients do not have a sensation of thirst. It is caused by infarction of the anterior hypothalamus where the osmoreceptors are located, which impairs their normal homeostatic thirsts mechanism despite the symptoms of DI.[3][24] Despite being dehydrated, the patient will not drink an adequate amount of water.

Evaluation

When a patient presents with a disorder of the neurohypophysis, its manifestation is most commonly related to a disorder of the antidiuretic hormone. The antidiuretic hormone affects the distal collecting duct, and its regulatory function is to increase free water reabsorption and promote indirect sodium excretion. Any disturbances related to this hormone can create sodium electrolyte abnormalities.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging, which is the gold standard for visualization of the anterior and posterior pituitary, should be ordered to find or rule out possible etiologies that can produce neurohypophysis dysfunction.

Diabetic Insipidus

Serum and urine sodium, serum and urine osmolality, hourly urine output, 24-hour urine volume, and specific gravity must be obtained. Central DI must be distinguished from nephrogenic DI. A water deprivation test can be used with or without desmopressin injection. In central DI, the vasopressin will correct urine osmolality while in nephrogenic DI, the correction will be suboptimal.[3][25][26]

Criteria for the diagnosis of central DI:

- Polyuria in two consecutive hours of > 300 ml/hr or 4 to 5 ml/kg/hr in two consecutive hours

- Polyuria > 3L/24 hours or > 2ml/kg/hr in 24 hours

- Serum osmolality > 300 mOsm/kg

- Urine osmolality < 300 mOsm/kg

- Urine/plasma osmolality < 1

- The specific gravity of less than 1.005

SIADH Secretion

The first step is to assess the fluid status and obtain laboratory tests to evaluate serum and urine sodium, serum and urine osmolality, blood sugar, potassium levels, and liver function. When SIADH secretion is suspected, it is important to order thyroid-stimulating hormone and thyroxine levels (TSH/T4), and serum cortisol to rule out glucocorticoid and thyroid hormone deficiency. The most common presentation in SIADH secretion will be hyponatremia with a euvolemic fluid status. Patients will have decrease plasma osmolality and increase sodium excretion.[3][27][28] Other causes of hyponatremia (adrenal insufficiency, hypothyroidism, cardiac failure, hepatic damage, renal disease, pituitary dysfunction, drugs) must be excluded.

Criteria for the diagnosis of SIADH secretion:[29][30]

- serum sodium < 135 mEq/L

- serum osmolality < 275 mOsm/kg

- Urine osmolality > 100 mOsm/kg

- Urine sodium > 30 mEq/L

- Normal dietary and water intake

- No recent use of diuretic agents

- Correction of deficit with fluid restriction

Treatment / Management

Diabetic Insipidus

The medication recommended in the acute and chronic setting of central DI is desmopressin.[31][32] Desmopressin, D-amino D-arginine vasopressin (DDAVP) is given intranasal, orally, and intravenous with a half-life of 8-20 hours. It is crucial to establish the dose that works to improve the patient's polyuria and polydipsia without compromise of the plasma serum electrolytes.[23] The water loss must be replaced. In acute DI after a TBI, it is mandatory to evaluate if the patient is conscious or unconscious. If the patient is conscious, encourage drinking. If the patient can not drink, enforce fluid intake by nasogastric tube guided by daily weighing. If the patient is unconscious, intravenous fluids of dextrose 5% are given. Treatment with DDAVP is administered at 10 mcg by nasal puff or 0.4 to 4 mcg subcutaneous or intravenous DDAVP. Maintenance is usually by 1 to 2 nasal puffs every 12 hours. Hypokalemia, if present, must be corrected. Urine volume, fluid balance, urine osmolality, plasma osmolality, and serum electrolytes must be monitored. The goal is to balance electrolytes and to have normal urine output. After desmopressin is given, it is essential to monitor sodium levels. In the management of hypernatremia in DI, it is vital to use dextrose or nasogastric water at a pace of lowering plasma sodium concentration at 0.5 mEq/L/hr or less.(B3)

SIADH Secretion

Fluid restriction is the primary treatment for SIADH secretion. Fluids should be reduced to 500 to 800 ml/day. Correction should be aimed to reach serum sodium of 130 mEq/L. If hyponatremia persists, the patient should receive salt tablets and furosemide 20 mg twice a day. Isotonic fluids will not correct the deficit; therefore, 3% hypertonic (513 mOsm/kg) should be given for severe hypernatremia. A bolus of 100 ml is given in 3 hours, and repeat bolus can be given as needed based on the serum electrolytes. In TBI, hypertonic saline will also help to reduce intracranial pressure. Correction should not be more than 8 mEq/L over 24 hours or 0.5 to 1 mEq/L per hour to prevent osmotic demyelination syndrome. For persistent hyponatremia, oral tolvaptan or intravenous conivaptan, which are vasopressin V2 receptor antagonists, are given.[4] Tolvaptan is hepatotoxicity and can not be given in patients with liver disease. Demeclocycline, which is a tetracycline vasopressin inhibitor, can be given but can produce side effects of reversible azotemia, cirrhosis, and photosensitive skin rashes.[33] Urea had also been used to decreases natriuresis and has been comparable to vaptans in the reversal of hyponatremia in SIADH secretion.[3](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

- Polydipsia

- Water intoxication

- Hypovolemia

- Nephrogenic DI

- Congestive heart failure

- Cirrhosis

- Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus

- Chronic nausea/vomiting

- Cerebral salt wasting syndrome

- SIADH secretion

- Inappropriate intravenous therapy

- Glucocorticoid deficiency

- Hypothyroidism

- Pseudohyponatremia (hyperglycemic and hyperlipidemic patients)

- Drugs that affect ADH (carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, chlorpropamide, cyclophosphamide, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors)

- Small cell lung cancer

- Non-pulmonary tumors secreting ADH-like substances

- Hypercalcemia

- Hypokalemia

- Histiocytosis

Prognosis

The prognosis for DI is excellent after the primary cause is treated. Hypernatremia can lead to cerebral herniation due to an increase in intracranial pressure. When DI has been diagnosticated in trauma patients, the majority recover in 2 to 4 days, and the remaining few recovers during a 6-month timeframe, which provides good patient outcomes. Permanent DI after TBI has a prevalence of 6%.[3][20] Acute onset DI in TBI increases the mortality rate.[21]

For acute SIADH secretion, the prognosis is related to the level of hyponatremia and its response to treatment. Hyponatremia is a major contributing factor to severe morbidity and mortality. The management of SIADH secretion is complex, and water restriction does not always correct the hyponatremia requiring further investigations and second-line treatments.[4]

Complications

Potential complications include:

- Hyponatremia

- Hypernatremia

- Confusion

- Seizures

- Muscle twitching

- Lethargy

- Coma

- Death

- Lack of breastfeeding

- Poor uterine contraction

- Poor cervix dilatation

- Poor sexual response

- Depression

Deterrence and Patient Education

The management of a patient with disorders of the neurohypophysis can be challenging in an intrahospital setting. In certain situations, complications can be avoided with early recognition of symptoms. The presentation due to sodium abnormalities can be varied but can progress to coma and death if untreated. The patient must be aware of any changes in urine volume or an increase in thirst sensation. The patient needs to recognize polyuria, increase thirst sensation, muscle weakness, twitching, and confusion. In the presence of any of those symptoms, immediate contact with the primary physician should be obtained for further assessment and evaluation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Disorders of neurohypophysis frequently present a diagnostic dilemma. Patients may exhibit non-specific signs and symptoms such as vomiting, nausea, hypernatremia, hyponatremia, and diuresis. The cause of disorders of the neurohypophysis may be due to a myriad of diagnoses, including tumoral, traumatic, inflammatory, infectious, and metabolic etiologies. The etiology is difficult to know without proper imaging studies.

The primary physician is usually the person in charge of the initial evaluation of the patient. The physician will determine if it is an emergency or non-emergent situation, and this will depend on the presenting symptoms. Usually, an acute presentation is associated with more aggressive symptoms and treatment, while chronic presentation can be managed more conservatively. The management will depend on the type of neurohypophysis disorder.

While the endocrinologist is almost always involved in the care of patients with disorders of the neurohypophysis, it is essential to consult with an interprofessional team of specialists that include a neurosurgeon and a neurologist. The nurses are also vital members of the interprofessional group as they will monitor the patient's vital signs and assist with the education of the patient and family. The pharmacist will provide analgesics, antiemetics, appropriate antibiotics, antiepileptic, and antidiuretic medications. The neuroradiologist can assist in determining the cause. Women of childbearing age presenting with disorders of the neurohypophysis can experience issues during labor and later with breastfeeding.

The outcomes of disorders of the neurohypophysis depend on the cause. However, to improve outcomes, prompt consultation with an interprofessional group of specialists is recommended. The care provided to the patient must use an integrated care pathway combined with an evidence-based approach to planning and evaluation of activities.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Amar AP, Weiss MH. Pituitary anatomy and physiology. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2003 Jan:14(1):11-23, v [PubMed PMID: 12690976]

Regal M, Páramo C, Sierra SM, Garcia-Mayor RV. Prevalence and incidence of hypopituitarism in an adult Caucasian population in northwestern Spain. Clinical endocrinology. 2001 Dec:55(6):735-40 [PubMed PMID: 11895214]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTudor RM, Thompson CJ. Posterior pituitary dysfunction following traumatic brain injury: review. Pituitary. 2019 Jun:22(3):296-304. doi: 10.1007/s11102-018-0917-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30334138]

Cuesta M,Thompson CJ, The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis (SIAD). Best practice [PubMed PMID: 27156757]

Takami H, Graffeo CS, Perry A, Giannini C, Daniels DJ. Epidemiology, natural history, and optimal management of neurohypophyseal germ cell tumors. Journal of neurosurgery. 2020 Feb 7:():1-9. doi: 10.3171/2019.10.JNS191136. Epub 2020 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 32032947]

Ruszała A, Wójcik M, Krystynowicz A, Starzyk J. Distinguishing between post-trauma pituitary stalk disruption and genetic pituitary stalk interruption syndrome - case presentation and literature overview. Pediatric endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism. 2019:25(3):155-162. doi: 10.5114/pedm.2019.87708. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31769274]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceXu C, Wang T, Feng Y. Pituitary Stalk Interruption Syndrome. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2019 Sep:30(6):e578-e580. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000005580. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31756884]

Vergier J, Castinetti F, Saveanu A, Girard N, Brue T, Reynaud R. DIAGNOSIS OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE: Pituitary stalk interruption syndrome: etiology and clinical manifestations. European journal of endocrinology. 2019 Nov:181(5):R199-R209. doi: 10.1530/EJE-19-0168. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31480013]

Gosi SK, Kanduri S, Garla VV. Pituitary stalk interruption syndrome. BMJ case reports. 2019 Apr 14:12(4):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-230133. Epub 2019 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 30988112]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLichiardopol C, Albulescu DM. PITUITARY STALK INTERRUPTION SYNDROME: REPORT OF TWO CASES AND LITERATURE REVIEW. Acta endocrinologica (Bucharest, Romania : 2005). 2017 Jan-Mar:13(1):96-105. doi: 10.4183/aeb.2017.96. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31149155]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVoutetakis A. Pituitary stalk interruption syndrome. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2021:181():9-27. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-820683-6.00002-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34238482]

Schaller B, Kirsch E, Tolnay M, Mindermann T. Symptomatic granular cell tumor of the pituitary gland: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1998 Jan:42(1):166-70; discussion 170-1 [PubMed PMID: 9442519]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTomita T, Gates E. Pituitary adenomas and granular cell tumors. Incidence, cell type, and location of tumor in 100 pituitary glands at autopsy. American journal of clinical pathology. 1999 Jun:111(6):817-25 [PubMed PMID: 10361519]

Cone L, Srinivasan M, Romanul FC. Granular cell tumor (choristoma) of the neurohypophysis: two cases and a review of the literature. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 1990 Mar-Apr:11(2):403-6 [PubMed PMID: 2156414]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCohen-Gadol AA, Pichelmann MA, Link MJ, Scheithauer BW, Krecke KN, Young WF Jr, Hardy J, Giannini C. Granular cell tumor of the sellar and suprasellar region: clinicopathologic study of 11 cases and literature review. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2003 May:78(5):567-73 [PubMed PMID: 12744543]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSaeger W, Lüdecke DK, Buchfelder M, Fahlbusch R, Quabbe HJ, Petersenn S. Pathohistological classification of pituitary tumors: 10 years of experience with the German Pituitary Tumor Registry. European journal of endocrinology. 2007 Feb:156(2):203-16 [PubMed PMID: 17287410]

Karaca Z, Laway BA, Dokmetas HS, Atmaca H, Kelestimur F. Sheehan syndrome. Nature reviews. Disease primers. 2016 Dec 22:2():16092. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.92. Epub 2016 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 28004764]

SCHALLY AV, BOWERS CY, LOCKE W. NEUROHUMORAL FUNCTIONS OF THE HYPOTHALAMUS. The American journal of the medical sciences. 1964 Jul:248():79-101 [PubMed PMID: 14181154]

Giusti-Paiva A, Santiago MB. Neurohypophyseal dysfunction during septic shock. Endocrine, metabolic & immune disorders drug targets. 2010 Sep:10(3):247-51 [PubMed PMID: 20509843]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAgha A, Sherlock M, Phillips J, Tormey W, Thompson CJ. The natural history of post-traumatic neurohypophysial dysfunction. European journal of endocrinology. 2005 Mar:152(3):371-7 [PubMed PMID: 15757853]

Capatina C, Paluzzi A, Mitchell R, Karavitaki N. Diabetes Insipidus after Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of clinical medicine. 2015 Jul 13:4(7):1448-62. doi: 10.3390/jcm4071448. Epub 2015 Jul 13 [PubMed PMID: 26239685]

Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hofland J, Kalra S, Kaltsas G, Kapoor N, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M, Kovacs CS, Kuohung W, Laferrère B, Levy M, McGee EA, McLachlan R, New M, Purnell J, Sahay R, Shah AS, Singer F, Sperling MA, Stratakis CA, Trence DL, Wilson DP, Larkin S, Ansorge O. Development And Microscopic Anatomy Of The Pituitary Gland. Endotext. 2000:(): [PubMed PMID: 28402619]

Lu HA. Diabetes Insipidus. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2017:969():213-225. doi: 10.1007/978-94-024-1057-0_14. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28258576]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDalan R, Chin H, Hoe J, Chen A, Tan H, Boehm BO, Chua KS. Adipsic Diabetes Insipidus-The Challenging Combination of Polyuria and Adipsia: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2019:10():630. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00630. Epub 2019 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 31620086]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFaltado AL, Macalalad-Josue AA, Li RJS, Quisumbing JPM, Yu MGY, Jimeno CA. Factors Associated with Postoperative Diabetes Insipidus after Pituitary Surgery. Endocrinology and metabolism (Seoul, Korea). 2017 Dec:32(4):426-433. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2017.32.4.426. Epub 2017 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 29199401]

Hunter JD, Calikoglu AS. Etiological and clinical characteristics of central diabetes insipidus in children: a single center experience. International journal of pediatric endocrinology. 2016:2016():3. doi: 10.1186/s13633-016-0021-y. Epub 2016 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 26870137]

Peri A, Grohé C, Berardi R, Runkle I. SIADH: differential diagnosis and clinical management. Endocrine. 2017 Jan:55(1):311-319. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-0936-3. Epub 2016 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 27025948]

Yasir M, Mechanic OJ. Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone Secretion. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29939554]

Silveira MAD, Seguro AC, da Silva JB, Arantes de Oliveira MF, Seabra VF, Reichert BV, Rodrigues CE, Andrade L. Chronic Hyponatremia Due to the Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuresis (SIAD) in an Adult Woman with Corpus Callosum Agenesis (CCA). The American journal of case reports. 2018 Nov 12:19():1345-1349. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.911810. Epub 2018 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 30416193]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBerardi R, Antonuzzo A, Blasi L, Buosi R, Lorusso V, Migliorino MR, Montesarchio V, Zilembo N, Sabbatini R, Peri A. Practical issues for the management of hyponatremia in oncology. Endocrine. 2018 Jul:61(1):158-164. doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1547-y. Epub 2018 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 29417373]

Baldeweg SE, Ball S, Brooke A, Gleeson HK, Levy MJ, Prentice M, Wass J, Society for Endocrinology Clinical Committee. SOCIETY FOR ENDOCRINOLOGY CLINICAL GUIDANCE: Inpatient management of cranial diabetes insipidus. Endocrine connections. 2018 Jul:7(7):G8-G11. doi: 10.1530/EC-18-0154. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29930026]

Hui C, Khan M, Khan Suheb MZ, Radbel JM. Diabetes Insipidus. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262153]

Miell J, Dhanjal P, Jamookeeah C. Evidence for the use of demeclocycline in the treatment of hyponatraemia secondary to SIADH: a systematic review. International journal of clinical practice. 2015 Dec:69(12):1396-417. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12713. Epub 2015 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 26289137]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence