Introduction

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare, chronic, and idiopathic disease characterized by collagen degeneration that causes skin lesions, typically on the anterior shin surface. This disease is classically associated with diabetes mellitus, typically type 1, and carries a risk of ulceration. Skin changes include thickening of the blood vessel walls, collagen deterioration, granuloma formation, and fat deposition. A major complication of the disease is ulcer formation, often occurring after trauma. Infections are uncommon. Moreover, if necrobiosis lipoidica becomes chronic, it may rarely progress to squamous cell carcinoma.[1][2][3]

Necrobiosis lipoidica was first mentioned as dermatitis atrophicans lipoidica diabetica by Oppenheim in 1929. However, in 1932, Urbach renamed the disease necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum. In 1935, the first case was reported by Goldsmith in a nondiabetic patient. Subsequently, in 1948, Meischer and Leder described more cases of nondiabetic patients. In 1960, Rollins and Winkelmann published further information about cases of nondiabetic patients. Hence, the suggestion was put forth to exclude diabetes mellitus from the name of the disease.[4] Today, a broader term—necrobiosis lipoidica—encompasses all patients with these characteristic lesions with or without diabetes mellitus.

Necrobiosis lipoidica is highly associated with diabetes mellitus and, particularly, high insulin requirements. However, necrobiosis lipoidica is also highly associated with metabolic syndrome, obesity, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, celiac disease, and autoimmune thyroid disease, suggesting additional causative etiologies. Necrobiosis lipoidica is a multifactorial skin disease with many possible contributing factors, for which ongoing new research and developments elucidate mechanisms for possible therapeutic interventions.[5][6]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Although a significant percentage of people with necrobiosis lipoidica have diabetes mellitus, only 0.3% to 1.2% of people with diabetes mellitus demonstrate necrobiosis lipoidica, pointing to a confluence of other factors that must be present for its development. The most common theory is that vascular disturbance involving immune complex deposition or microangiopathic changes leads to collagen degeneration.[7]

In addition to diabetes mellitus, other conditions are associated with necrobiosis lipoidica. A study found the incidence of thyroid disease to be 3 times the expected value, and autoimmune thyroid disease was especially prevalent. Two large studies found that thyroid disease is over 25% in necrobiosis lipoidica associated with and without diabetes mellitus.[5][25] Second only to diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension was also found in a large proportion of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica. Other commonly associated diseases were hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, obesity, metabolic syndrome, celiac disease, and other autoimmune diseases, such as sarcoidosis and multiple sclerosis.[5][8][9]

Several theories have been proposed regarding the etiology of necrobiosis lipoidica.

Diabetic Microangiopathy

Given the strong association between diabetes mellitus and necrobiosis lipoidica, several studies have emphasized diabetic microangiopathy as a prime etiological factor.[10] Further support lies in the fact that the diabetic effects on the ocular and renal vasculature are comparable to the vascular changes observed in necrobiosis lipoidica. In addition, glycoprotein deposition has been described in blood vessel walls with diabetic microangiopathy and necrobiosis lipoidica.

Immunoglobulins, Complement, and Fibrinogen

A proposed theory suggests that the deposition of immunoglobulins, C3, and fibrinogen in vascular walls triggers the development of necrobiosis lipoidica.[9][11] Some argue that an antibody-mediated reaction may initiate the blood vessel changes leading to necrobiosis, suggesting that immunoglobulin M (IgM) deposits may be significant. These deposits are often found at the dermal-epidermal junction.[9][12]

Abnormal Collagen

Another theory suggests that the etiology of necrobiosis lipoidica is associated with abnormal collagen. Abnormal collagen fibrils are known to contribute to diabetes mellitus–related end-organ damage and expedited aging. In diabetes mellitus, elevated levels of lysyl oxidase lead to increased collagen cross-linking. This increase in collagen cross-linking could cause the thickening of the basement membrane in necrobiosis lipoidica.

Impaired Neutrophil Migration

Another possible causative factor is defective neutrophil migration, resulting in increased macrophage activity. Macrophage activation may lead to granuloma formation.[13]

Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) has been observed to play a crucial role in granulomatous diseases such as necrobiosis lipoidica and disseminated granuloma.[14] Levels are raised in the sera and skin of patients suffering from these conditions.

Epidemiology

Over half of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica have diabetes mellitus, although this association is not uniform. The incidence among people with diabetes mellitus is only 0.3% to 1.2%.[15] Necrobiosis lipoidica precedes diabetes mellitus in up to 14%, appears simultaneously in up to 24% of cases, and occurs after diabetes mellitus is diagnosed in about 62% of cases. No definitive connection exists between the level of glycemic control and the likelihood of developing necrobiosis lipoidica.

Although necrobiosis lipoidica may present in healthy individuals with no known disease, other commonly associated conditions are thyroid disorders and inflammatory diseases, including Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and sarcoidosis. A predominance of about 3:1 for females is noted and is especially prevalent in patients with diabetes mellitus.[16]

The average age of onset for necrobiosis lipoidica is the third decade of life in patients with type 1 diabetes and the fourth decade of life in those with type 2 diabetes or without diabetes mellitus. Some studies demonstrate that ulceration, observed in about one-third of patients, is most prevalent in men and patients with diabetes mellitus.[17]

Pathophysiology

The characteristic skin lesions of necrobiosis lipoidica are marked by collagen deterioration, granuloma formation, fat deposition, and blood vessel thickening. The lesions often start as several well-defined nodules or papules, which coalesce into a larger plaque. The plaque coloring is often yellowish- or reddish-brown, and the central core demonstrates distinct characteristics such as atrophy, waxiness, or necrosis, distinct from the outer regions.[5] Telangiectasias can result from collagen degeneration. As the plaques progress, they become more vulnerable to injury, and painful ulcerations occur in about 30% of cases.[5][6]

An immunologically mediated vascular disease has been suggested as the primary cause of the altered collagen. The most common vascular abnormalities observed are thickening of the vessel walls, fibrosis, and endothelial proliferation, leading to occlusion in the deeper dermis, especially in patients with diabetes mellitus. Deposition of fibrin, IgM, and C3 at the dermo-epidermal junction of blood vessels has been shown in immunofluorescence studies.[18]

The concentration of collagen decreases in necrobiosis lipoidica, and electron microscopy shows a loss of the cross-striations of collagen fibrils and an essential variation in the diameter of individual fibrils. Fibroblasts cultured from necrobiosis lipoidica synthesize less collagen compared to their counterparts from the unaffected skin.[19]

Histopathology

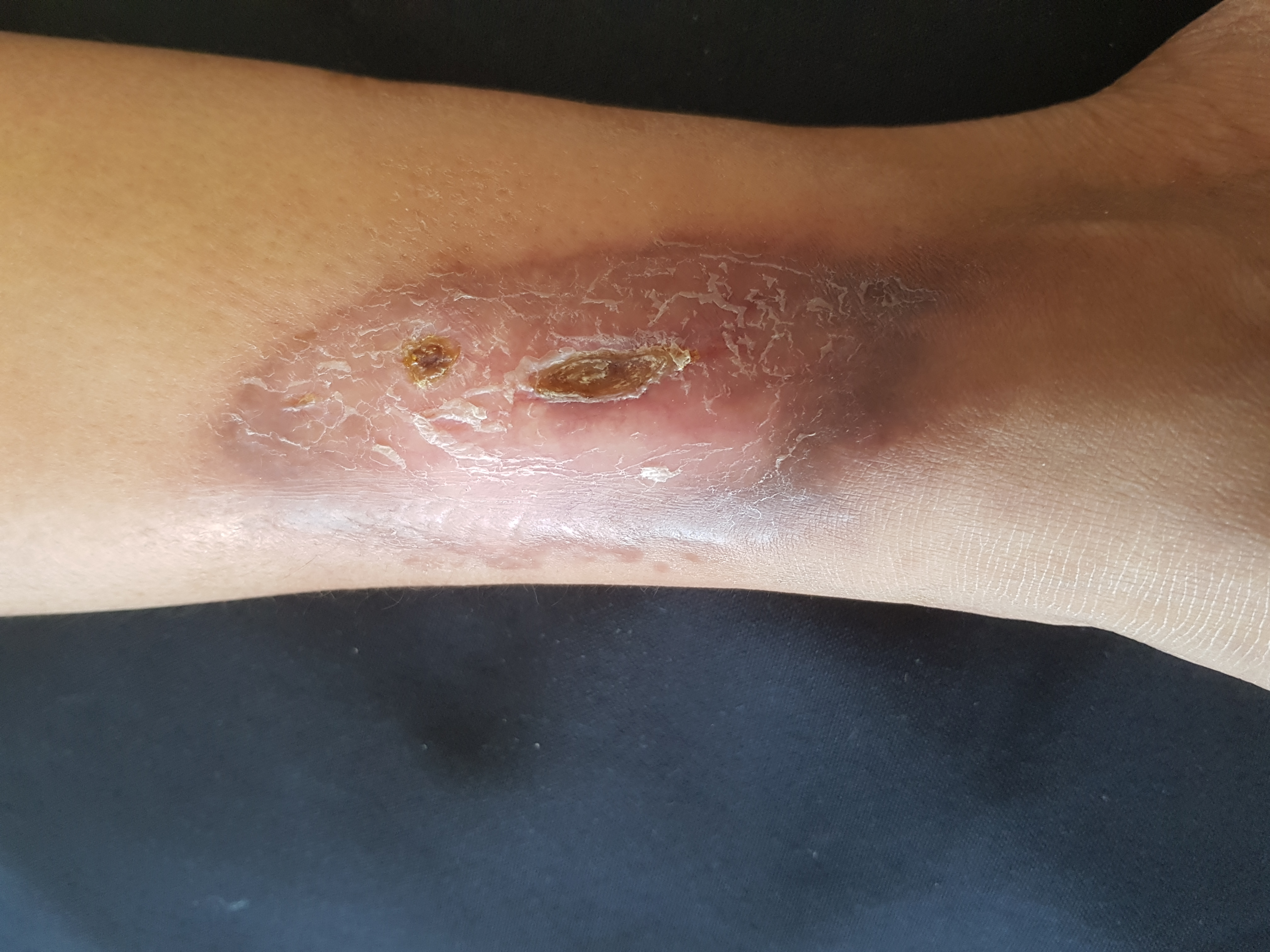

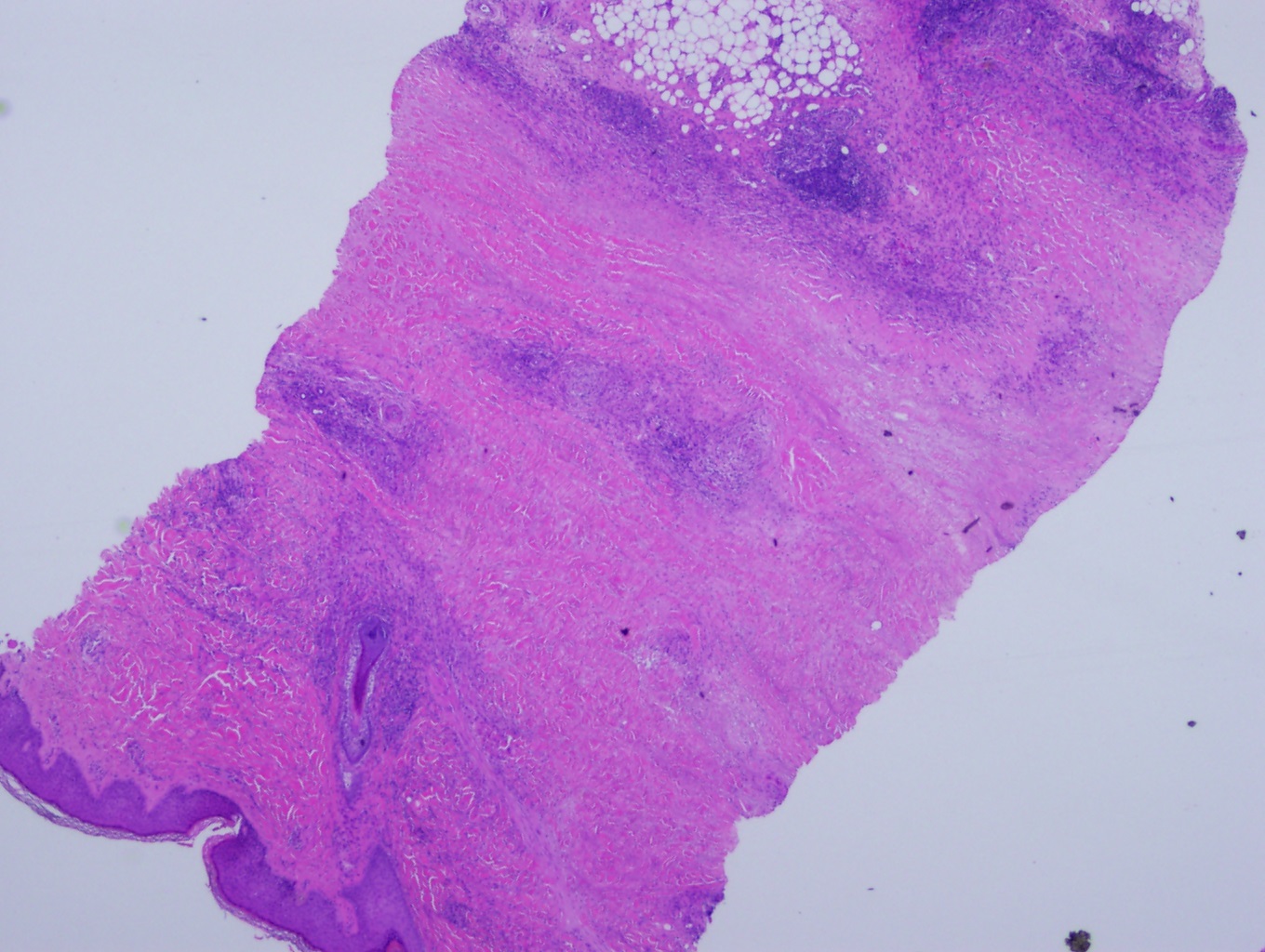

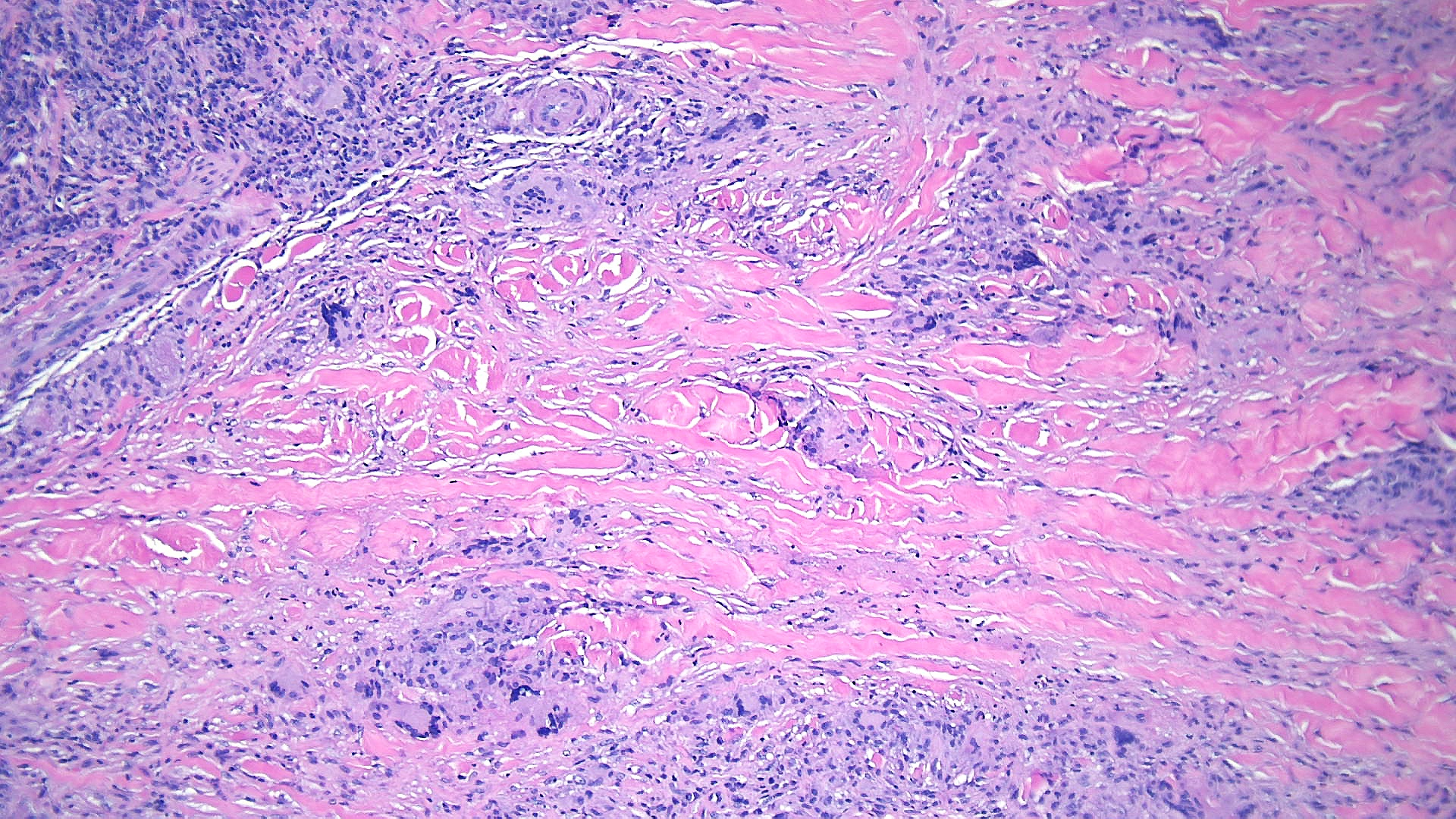

The prime histopathological findings include endothelial cell swelling and thickening of the blood vessel walls from the middle to the deep dermis, a characteristic also observed in diabetic microangiopathy. Necrobiosis lipoidica lesions in patients with diabetes mellitus tend to show palisade granulomas surrounding necrobiotic areas, whereas lesions in patients without diabetes mellitus tend to be more tubercular (see Images Necrobiosis Lipoidica, Lower Extremities and Necrobiosis Lipoidica, Ulcerated).[11]

Histopathologically, biopsy specimens from the palpable inflammatory border reveal scattered palisaded and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, with layered tiers of granulomatous inflammation parallel to the skin surface, involving the entire dermis and extending into the subcutaneous fat septae. The granulomas comprise histiocytes, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils and are organized around patches of collagen degeneration. Decreased or loss of nerve cells is common. The epidermis is normal or atrophic. Focal loss of elastic tissue can be observed in areas of connective tissue sclerosis. Unlike granuloma annulare, there is no significant mucin deposition in the center of the palisading granulomas (see Images. Low-Power Histological Findings of Necrobiosis Lipoidica; High-Power Pathological Findings of Necrobiosis Lipoidica: Skin Biopsy; and Pathological Findings of Necrobiosis Lipoidica: Skin Biopsy).[5]

Direct immunofluorescence microscopy shows the presence of IgM, IgA, fibrinogen, and C3 in the blood vessels, leading to vascular thickening.[20]

Some studies have shown that necrobiosis lipoidica can be differentiated from other conditions using dermoscopy. A study found that cutaneous sarcoidosis granulomas can be distinguished from necrobiotic granulomas by their dermoscopic features, including a pink homogenous background, white scarlike depigmentation, translucent orange regions, and fine white scales.[21] When comparing necrobiosis lipoidica with granulomatous annulare, dermoscopy in necrobiosis lipoidica reveals sharply focused, elongated, and serpentine telangiectasias over a whitish, structureless background. In contrast, granulomatous annulare shows peripheral, structureless orange-reddish borders and isolated, unfocused small vessels.[22]

History and Physical

Necrobiosis lipoidica is characterized by yellow-brown, atrophic, telangiectatic plaques with an elevated violaceous rim, typically present in the pretibial surface. The lower extremities are the only location of lesions in 85% of cases; less typical anatomic locations include the upper extremities, face, scalp, trunk, upper extremities, or penis.[11]

Lesions typically begin as small, firm, 1- to 3-mm reddish-brown papules that gradually enlarge and then coalesce into plaques with indurated borders and waxy centers. Initially, these plaques are red to brown but progress to become more yellow, shiny, and atrophic. The plaques are typically multiple and bilateral. Ulceration occurs in approximately one-third of lesions, typically following minor trauma.[5] The disease course appears more severe in men as they have a higher likelihood of ulceration, reported in 58% of males compared to 15% of females. A study revealed that 17% of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica experienced spontaneous regression of the ulcerations, but the majority of cases persist without treatment (see Images. Necrobiosis Lipoidica, Lower Extremities and Necrobiosis Lipoidica, Ulcerated).[5][11][16]

Decreased sensation to pinprick and fine touch, hypohidrosis, and partial alopecia can be found within necrobiosis lipoidica plaques related to nerve loss. The lesions can also be painful, pruritic, or associated with paraesthesia. Some patients report reduced sensation or sweat over these lesions. Rare reports show squamous cell carcinoma developing within lesions of necrobiosis lipoidica.[11]

Koebner phenomena, an isomorphic response to trauma, injury, or surgery, can also result in further lesions.

Evaluation

Baseline blood work should include fasting blood glucose or glycosylated hemoglobin to screen for diabetes mellitus and assess glycemic control in patients known to have diabetes mellitus. If these tests are not diagnostic, they should be repeated every year, as necrobiosis lipoidica can be the first presentation of diabetes mellitus. Given the significant association with thyroid disease, checking thyroid-stimulating hormone, free thyroxine levels, and thyroperoxidase antibodies is also reasonable. If any gastrointestinal symptoms or signs of celiac disease are present, tissue transglutaminase, endomysial, and reticulin antibodies should be evaluated. Any other signs of autoimmune disease, such as additional skin or joint symptoms, should prompt evaluation for rheumatologic disease.

Although the diagnosis is often based on clinical examination, a biopsy should be performed to differentiate necrobiosis lipoidica from conditions with similar clinical appearances, including granuloma annulare and necrobiotic xanthogranuloma.

If there is a concern for venous or peripheral arterial disease, further vascular studies should be considered, including vascular ultrasound, computed tomography angiography, or angiogram.

Treatment / Management

No treatment has proven to be definitively effective in necrobiosis lipoidica. In the absence of ulceration or symptoms, some clinicians choose watchful waiting. Compression therapy controls edema and promotes healing in patients with associated venous disease or lymphedema.[6][23][24] Proper wound care principles are essential when ulcerations are present. Strict glucose monitoring has not shown symptom improvement in the short-term but likely helps slow disease progression, and post-pancreatic transplant patients often demonstrate resolution of necrobiosis lipoidica.[5](B3)

First-line therapy includes potent topical corticosteroids for early lesions and intralesional corticosteroids injected into the active borders of established lesions. For inactive, atrophic lesions, topical steroids should be avoided as they may exacerbate the atrophy and increase the risk of new ulcerations.[11] but caution is necessary due to the risk of associated hyperglycemia.[25] (B3)

Some studies found topical tacrolimus to be more effective compared to topical steroids; tacrolimus also does not worsen atrophic lesions.[26][27](B3)

Other systemic immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory agents used include fumarate esters, dapsone, and oral calcineurin inhibitors.[25][27][28][29][30] Systemic cyclosporine has also been described as effective in treating necrobiosis lipoidica lesions.[15] Other traditional anti-inflammatory/immunomodulating agents, such as chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, and mycophenolate mofetil, have also been used for necrobiosis lipoidica lesions with improvement.[27][31](A1)

Ultraviolet (UV) light therapy is used for various inflammatory dermatoses and is believed to provide local immunosuppression to the affected areas.[25] Psoralen and ultraviolet light A (PUVA) decrease the actively inflamed borders but have no clinical effects on atrophic scars.[15][24] In addition, a review found that up to 50% of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica showed no response to PUVA.[31] (A1)

Another treatment approach using UV light is photodynamic therapy. This treatment uses the interaction between photosensitizing agents such as 5-aminolaevulinic acid or its methylated ester by applying these agents to the skin before treatment. Then, UV light and molecular oxygen are used to induce localized cytotoxicity. This approach has been used in various dermatologic conditions and has proven effective in refractory necrobiosis lipoidica.[12]

Antiplatelet aggregation therapy with dipyridamole and aspirin has been tried based on the theory that necrobiosis lipoidica is due to platelet-mediated vascular occlusion or altered platelet survival. Results from various studies indicate both improvement and worsening of lesions, so there is no definitive evidence to support or refute their use.[15][32] However, pentoxifylline, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor used to improve peripheral blood flow through decreased blood viscosity, has been used successfully.[15][31](A1)

TNF is an essential regulator of granuloma formation. The monoclonal antibodies adalimumab and infliximab bind directly to soluble TNF-α to prevent its action. Etanercept is a fusion protein comprising the Fc portion of human IgG1 and TNF receptors that also inhibit TNF function. Both etanercept and infliximab have been reported to be effective as monotherapy for ulcerating necrobiosis lipoidica. A meta-analysis found that 70% of necrobiosis lipoidica lesions showed complete regression when using TNF-α inhibitors.[31] JAK/STAT inhibitors have also been used as immunomodulators to treat necrobiosis lipoidica.[33]

Hyperbaric oxygen has long been used for chronic and nonhealing wounds. A case study demonstrated the resolution of necrobiosis lipoidica in a patient with diabetes mellitus who was refractory to traditional treatment. The hyperbaric oxygen was used in conjunction with topical treatment.[34]

Surgical excision with skin grafting has also been employed to treat necrobiosis lipoidica, particularly in cases with ulceration unresponsive to more conservative treatment.[5][35](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical presentation of necrobiosis lipoidica is distinct, but many atypical appearances still exist, and early presentations can be hard to recognize.[36] The following are some important considerations for differential diagnoses:

- Acute complications of sarcoidosis

- Granuloma annulare

- Hematologic malignancies

- Paraproteinemia

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Sarcoidosis

- Xanthogranuloma

- Xanthomas

The primary differential diagnoses that require differentiation are granuloma annulare, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, sarcoidosis, diabetic dermopathy, and lipodermatosclerosis. Granuloma annulare and sarcoidosis lesions generally do not exhibit the same degree of atrophy, telangiectasias, or yellow-brown color as necrobiosis lipoidica does. In addition, the appearance of lipids and decreased amount of mucin in necrobiosis lipoidica help differentiate this from granuloma annulare.[37]

Prognosis

As the management of necrobiosis lipoidica is not very reassuring, its prognosis is also not very satisfactory. The disease is classically chronic, with variable progression. Squamous cell cancers can be found in more chronic lesions of necrobiosis lipoidica associated with previous trauma and ulceration.[1]

From an aesthetic viewpoint, the prognosis of necrobiosis lipoidica is not reassuring. Treatment can help halt the expansion of lesions that tend to have a chronic course. Lesional ulcerations can result in significant morbidity, requiring comprehensive wound care. These ulcers can be painful, may become infected, or often heal with scarring.

A concerning complication is the increased incidence of squamous cell carcinoma. Necrobiosis lipoidica is often present for decades before this develops. However, it is unknown whether chronic inflammation or other factors cause this, but this should be closely monitored.[38]

Complications

Complications of necrobiosis lipoidica include:

- Long-term scarring

- Infection

- Sepsis

- Squamous cell cancer

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with diseases associated with necrobiosis lipoidica should be made aware of the clinical presentation so that if the lesions occur, patients may contact their primary care practitioners. The early presentation helps ensure a better prognosis. Patients should also be made aware of the drug treatments available and their possible adverse effects. Once an ulcer is diagnosed, community wound nurses should educate patients about proper wound care. Avoiding trauma to the lesions, which can result in ulceration, should be emphasized.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare skin complication of type 1 diabetes and other metabolic and autoimmune conditions. However, its diagnosis and management are exceedingly complex. Effective management of skin lesions requires an interprofessional team comprising dermatologists, endocrinologists, wound care nurses, internists, and infectious disease specialists. Pharmacists play a crucial role in educating patients on prescribed medications, and social workers help transition patients to outpatient care and ensure appropriate services are in place. Wound care nurses are essential for managing open wounds and ulcers. These patients need long-term follow-up, as wound closure can take months. Some people may benefit from compression therapy and stockings.

All members of the interprofessional healthcare team must contribute from their area of expertise and maintain open communication channels with the rest of the team, particularly if the patient's condition deteriorates. Open communication also includes keeping accurate and updated patient records so that everyone involved in the case can access the same up-to-date patient data. With coordinated effort, cohesive action, and good interprofessional communication, these challenging cases can achieve the best positive outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Lim C, Tschuchnigg M, Lim J. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in an area of long-standing necrobiosis lipoidica. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2006 Aug:33(8):581-3 [PubMed PMID: 16919034]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceClement M, Guy R, Pembroke AC. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in long-standing necrobiosis lipoidica. Archives of dermatology. 1985 Jan:121(1):24-5 [PubMed PMID: 3966816]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLepe K, Riley CA, Salazar FJ. Necrobiosis Lipoidica. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083569]

ROLLINS TG, WINKELMANN RK. Necrobiosis lipoidica granulomatosis. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum in the nondiabetic. Archives of dermatology. 1960 Oct:82():537-43 [PubMed PMID: 13742950]

Ionescu C, Petca A, Dumitrașcu MC, Petca RC, Ionescu Miron AI, Șandru F. The Intersection of Dermatological Dilemmas and Endocrinological Complexities: Understanding Necrobiosis Lipoidica-A Comprehensive Review. Biomedicines. 2024 Feb 1:12(2):. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines12020337. Epub 2024 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 38397939]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHashemi DA, Brown-Joel ZO, Tkachenko E, Nelson CA, Noe MH, Imadojemu S, Vleugels RA, Mostaghimi A, Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Clinical Features and Comorbidities of Patients With Necrobiosis Lipoidica With or Without Diabetes. JAMA dermatology. 2019 Apr 1:155(4):455-459. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5635. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30785603]

Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis Lipoidica. Dermatologic clinics. 2015 Jul:33(3):343-60. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26143418]

Bearzi P, Trunfio F, Coppola R, Currado D, Conforti C, Zanframundo S, Nibid L, Donati M, Panasiti V, Navarini L, Giacomelli R. Necrobiosis-Lipoidica-Like Skin Lesions in a Patient with Non-Systemic Sarcoidosis. Dermatology practical & conceptual. 2023 Jul 1:13(3):. doi: 10.5826/dpc.1303a183. Epub 2023 Jul 1 [PubMed PMID: 37557149]

Hammer E, Lilienthal E, Hofer SE, Schulz S, Bollow E, Holl RW, DPV Initiative and the German BMBF Competence Network for Diabetes Mellitus. Risk factors for necrobiosis lipoidica in Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association. 2017 Jan:34(1):86-92. doi: 10.1111/dme.13138. Epub 2016 May 21 [PubMed PMID: 27101431]

Reid SD, Ladizinski B, Lee K, Baibergenova A, Alavi A. Update on necrobiosis lipoidica: a review of etiology, diagnosis, and treatment options. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2013 Nov:69(5):783-791. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.05.034. Epub 2013 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 23969033]

Naumowicz M, Modzelewski S, Macko A, Łuniewski B, Baran A, Flisiak I. A Breakthrough in the Treatment of Necrobiosis Lipoidica? Update on Treatment, Etiopathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Clinical Presentation. International journal of molecular sciences. 2024 Mar 20:25(6):. doi: 10.3390/ijms25063482. Epub 2024 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 38542454]

Li Pomi F, Motolese A, Paganelli A, Vaccaro M, Motolese A, Borgia F. Shedding Light on Photodynamic Therapy in the Treatment of Necrobiosis Lipoidica: A Multicenter Real-Life Experience. International journal of molecular sciences. 2024 Mar 23:25(7):. doi: 10.3390/ijms25073608. Epub 2024 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 38612420]

Franklin C, Stoffels-Weindorf M, Hillen U, Dissemond J. Ulcerated necrobiosis lipoidica as a rare cause for chronic leg ulcers: case report series of ten patients. International wound journal. 2015 Oct:12(5):548-54. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12159. Epub 2013 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 24119190]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEhlers S. Tumor necrosis factor and its blockade in granulomatous infections: differential modes of action of infliximab and etanercept? Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2005 Aug 1:41 Suppl 3():S199-203 [PubMed PMID: 15983900]

Feily A, Mehraban S. Treatment Modalities of Necrobiosis Lipoidica: A Concise Systematic Review. Dermatology reports. 2015 May 21:7(2):5749. doi: 10.4081/dr.2015.5749. Epub 2015 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 26236446]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceErfurt-Berge C, Seitz AT, Rehse C, Wollina U, Schwede K, Renner R. Update on clinical and laboratory features in necrobiosis lipoidica: a retrospective multicentre study of 52 patients. European journal of dermatology : EJD. 2012 Nov-Dec:22(6):770-5. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2012.1839. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23114030]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceErfurt-Berge C, Dissemond J, Schwede K, Seitz AT, Al Ghazal P, Wollina U, Renner R. Updated results of 100 patients on clinical features and therapeutic options in necrobiosis lipoidica in a retrospective multicentre study. European journal of dermatology : EJD. 2015 Nov-Dec:25(6):595-601. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2015.2636. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26575980]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceQuimby SR, Muller SA, Schroeter AL. The cutaneous immunopathology of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum. Archives of dermatology. 1988 Sep:124(9):1364-71 [PubMed PMID: 3046497]

Gebauer K, Armstrong M. Koebner phenomenon with necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum. International journal of dermatology. 1993 Dec:32(12):895-6 [PubMed PMID: 8125696]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUllman S, Dahl MV. Necrobiosis lipoidica. An immunofluorescence study. Archives of dermatology. 1977 Dec:113(12):1671-3 [PubMed PMID: 596895]

Ramadan S, Hossam D, Saleh MA. Dermoscopy could be useful in differentiating sarcoidosis from necrobiotic granulomas even after treatment with systemic steroids. Dermatology practical & conceptual. 2016 Jul:6(3):17-22. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0603a05. Epub 2016 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 27648379]

Pellicano R, Caldarola G, Filabozzi P, Zalaudek I. Dermoscopy of necrobiosis lipoidica and granuloma annulare. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland). 2013:226(4):319-23. doi: 10.1159/000350573. Epub 2013 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 23797090]

Fertitta L, Vignon-Pennamen MD, Frazier A, Guibal F, Caumes E, Bagot M, Bouaziz JD, Frumholtz L. Necrobiosis lipoidica with bone involvement successfully treated with infliximab. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2019 Sep 1:58(9):1702-1703. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez055. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30877774]

Tong LX, Penn L, Meehan SA, Kim RH. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatology online journal. 2018 Dec 15:24(12):. pii: 13030/qt0qg3b3zw. Epub 2018 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 30677798]

Eberle FC, Ghoreschi K, Hertl M. Fumaric acid esters in severe ulcerative necrobiosis lipoidica: a case report and evaluation of current therapies. Acta dermato-venereologica. 2010:90(1):104-6. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0757. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20107745]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceErfurt-Berge C, Heusinger V, Reinboldt-Jockenhöfer F, Dissemond J, Renner R. Comorbidity and Therapeutic Approaches in Patients with Necrobiosis Lipoidica. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland). 2022:238(1):148-155. doi: 10.1159/000514687. Epub 2021 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 33827092]

Ginocchio L, Draghi L, Darvishian F, Ross FL. Refractory Ulcerated Necrobiosis Lipoidica: Closure of a Difficult Wound with Topical Tacrolimus. Advances in skin & wound care. 2017 Oct:30(10):469-472. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000521867.98577.a5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28914682]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceImadojemu S, Rosenbach M. Advances in Inflammatory Granulomatous Skin Diseases. Dermatologic clinics. 2019 Jan:37(1):49-64. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2018.08.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30466688]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDissemond J, Erfurt-Berge C, Goerge T, Kröger K, Funke-Lorenz C, Reich-Schupke S. Systemic therapies for leg ulcers. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft = Journal of the German Society of Dermatology : JDDG. 2018 Jul:16(7):873-890. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13586. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29989361]

Lause M, Kamboj A, Fernandez Faith E. Dermatologic manifestations of endocrine disorders. Translational pediatrics. 2017 Oct:6(4):300-312. doi: 10.21037/tp.2017.09.08. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29184811]

Peckruhn M, Tittelbach J, Elsner P. Update: Treatment of necrobiosis lipoidica. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft = Journal of the German Society of Dermatology : JDDG. 2017 Feb:15(2):151-157. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13186. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28214312]

. Treatment of diabetic necrobiosis with aspirin or dipyridamole. The New England journal of medicine. 1978 Dec 14:299(24):1366 [PubMed PMID: 714111]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHwang AS, Kechter JA, Li X, Hughes A, Severson KJ, Boudreaux B, Bhullar P, Nassir S, Yousif M, Zhang N, Butterfield RJ, Nelson S, Xing X, Tsoi LC, Zunich S, Sekulic A, Pittelkow M, Gudjonsson JE, Mangold A. Topical Ruxolitinib in the Treatment of Necrobiosis Lipoidica: A Prospective, Open-Label Study. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2024 Feb 27:():. pii: S0022-202X(24)00159-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2023.11.027. Epub 2024 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 38417541]

Weisz G, Ramon Y, Waisman D, Melamed Y. Treatment of necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum by hyperbaric oxygen. Acta dermato-venereologica. 1993 Dec:73(6):447-8 [PubMed PMID: 7906460]

Owen CM, Murphy H, Yates VM. Tissue-engineered dermal skin grafting in the treatment of ulcerated necrobiosis lipoidica. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2001 Mar:26(2):176-8 [PubMed PMID: 11298110]

Mistry N, Chih-Ho Hong H, Crawford RI. Pretibial angioplasia: a novel entity encompassing the clinical features of necrobiosis lipoidica and the histopathology of venous insufficiency. Journal of cutaneous medicine and surgery. 2011 Jan-Feb:15(1):15-20 [PubMed PMID: 21291651]

Hawryluk EB, Izikson L, English JC 3rd. Non-infectious granulomatous diseases of the skin and their associated systemic diseases: an evidence-based update to important clinical questions. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2010:11(3):171-81. doi: 10.2165/11530080-000000000-00000. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20184390]

Kuraitis D, Murina A. Squamous Cell Carcinoma Arising in Chronic Inflammatory Dermatoses. Cutis. 2024 Jan:113(1):29-34. doi: 10.12788/cutis.0914. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38478947]