Introduction

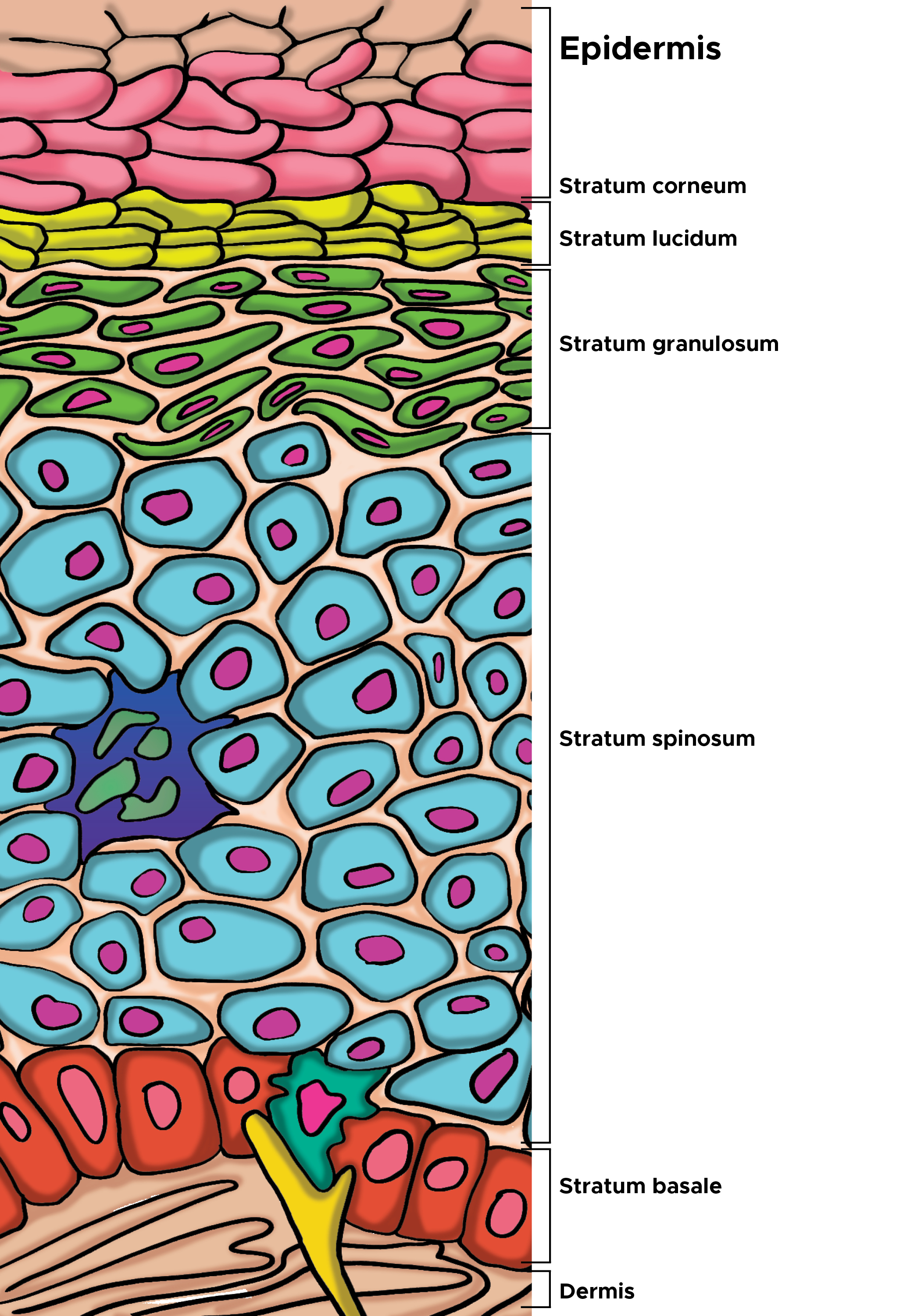

As the outermost layer of the epidermis, the stratum corneum is the first line of defense for the body, serving an essential role as a protective skin barrier against the external environment. The stratum corneum aids in hydration and water retention, which prevents skin cracking, and is made up of corneocytes, which are anucleated keratinocytes that have reached the final stage of keratinocyte differentiation. Corneocytes retain keratin filaments within a filaggrin matrix, and the cornified lipid envelope replaces the keratinocyte plasma membrane. These flat cells organize in a brick-and-mortar formation within a lipid-rich extracellular matrix. Pathophysiology of the stratum corneum is typically secondary to either protein or lipid defects (see Image. Cells of the Epidermis). Other clinically significant signs include parakeratosis, which is the incomplete maturation of keratinocytes, and the morphological retention of nuclei in the stratum corneum. Abnormal parakeratosis of the stratum corneum can appear in patients with psoriasis, chronic eczema, and squamous cell carcinoma.[1] Scaling, or visible peeling and flaking of the skin, furthermore is a salient manifestation of diseases of the stratum corneum.[2][3][4]

Structure

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure

The stratum corneum is the outermost layer of the epidermis and marks the final stage of keratinocyte maturation and development. Keratinocytes at the basal layer of the epidermis are proliferative, and as the cells mature up the epidermis, they slowly lose proliferative potential and undergo programmed destruction. These finally differentiated, enucleated keratinocytes are termed corneocytes and retain only keratin filaments embedded in filaggrin matrix. Cornified lipid envelopes replace the plasma membranes of the previous keratinocytes, and the cells flatten, connecting to one another with corneodesmosomes and stacking as layers to form the stratum corneum. This outermost barrier level is made up of a network of corneocytes and an extracellular lipid matrix. The stratum corneum functions as a 2-compartment system, with the hydrophobic, protein-rich corneocytes sequestered in a lipid-enriched matrix. This network is organized in a “bricks and mortar” formation, with the extracellular matrix organizing into lamellar membranes.[5][6] The human stratum corneum comprises 15 or so layers of flattened corneocytes and is divided into 2 layers: the stratum compactum and the stratum disjunctum. The stratum compactum is the deep, dense, cohesive layer, while the stratum disjunctum is looser and lies superficially to the stratum compactum. As the stratum disjunctum continues to lose adhesiveness secondary to decreased inter-corneocyte adhesion, the cells desquamate.

Function

The stratum corneum serves as the body's first barrier from the external environment. For the keratinocytes produced in the stratum basale, the goal is differentiation to the anucleated corneocytes that make up the stratum corneum. This most superficial layer of the epithelium prevents desiccation and serves as a shield against the environment. The 2 components of the stratum corneum, the extracellular lipid matrix and the corneocytes, serve different functions. The corneocytes, which are the terminally differentiated keratinocytes, provide mechanical reinforcement, protect underlying mitotically active cells from ultraviolet (UV) damage, regulate cytokine-mediated initiation of inflammation, and maintain hydration. The extracellular lipid matrix that creates the brick-and-mortar organization of the stratum corneum regulates permeability, initiates corneocyte desquamation, has antimicrobial peptide activity, and excludes toxins, and allows for selective chemical absorption.[7][8][9][10]

Tissue Preparation

Collecting the stratum corneum layer for additional staining and analysis can be achieved in different ways, determined by the desired functionality of the collected sample. Simple scrapings and smears allow for the collection of the stratum corneum corneocytes but do not preserve tissue architecture. The tape stripping technique can be used to collect the stratum disjunctum layer specifically. In this technique, an adhesive tape strip is applied to the skin with even pressure. The strip is removed, and the stratum disjunctum pulls away with it, captured on the adhesive surface. Finally, the stratum corneum can be visualized in hematoxylin and eosin staining of skin biopsies and excisional samples.

Microscopy, Light

The stratum corneum can be visualized by examining sectioned epidermal tissue under hematoxylin and eosin staining under light microscopy. The corneocytes present in the stratum corneum are flat, eosinophilic cells that lack nuclei. The stratum compactum and stratum disjunctum layers can generally be visualized easily.

Microscopy, Electron

Scanning electron microscopy can also provide a more detailed three-dimensional examination of the stratum corneum. Skin biopsies of the cells are first coated with a carbon layer and then mounted onto glass slides. Under the microscope, the clarity of the cells' surface characteristics, like grooves, folds, and convolutions, can help differentiate healthy individual stratum corneum cells from their pathological counterparts, such as psoriatic cells and bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma.[11]

Pathophysiology

Defects in the stratum corneum may occur secondary to lipid or protein dysfunction. Lipid abnormalities may stem from a variety of causes and generally result in defective barrier function, resulting in increased transepidermal water loss and desquamation. An acute loss of lipids from the stratum corneum may occur secondary to the topical application of organic solvents or detergents, which extract lipids and allow the passive loss of extracellular calcium and potassium. Deficiency in essential fatty acids also results in lipid abnormalities and manifests as increased transepidermal water loss, scaling, and alopecia. Lipid abnormalities can also occur secondary to genetic disorders, such as deficiency in steroid sulfatase leading to recessive X-linked ichthyosis.

In addition to pathologies secondary to lipid abnormalities, stratum corneum protein abnormalities can also result in defects in the stratum corneum layer of the epidermis. Defects in corneodesmosomes, the junctional proteins that connect corneocytes, result in diseases such as peeling skin disease. Defects in the profilaggrin and filaggrin proteins cause significant damage to the stratum corneum, and profilaggrin defects are associated with both ichthyosis vulgaris and harlequin ichthyosis. Defects in the cornified envelopes of the stratum corneum cells can also result in pathologies such as keratosis follicularis and psoriasis. Finally, parakeratosis refers to corneocytes in the stratum corneum with retained nuclei. While retention of nuclei in stratum corneum cells is normal in mucosal surfaces, parakeratosis in other skin is abnormal. Parakeratosis typically signifies increased cell turnover, which can be secondary to inflammatory or neoplastic processes. Additionally, when corneocytes retain their nuclei, there is associated thinning and eventual loss of the granular layer.

Clinical Significance

Scaling is the most common clinical manifestation of stratum corneum disease and represents inadequate or flawed keratinization and desquamation. Those diseases characterized by scaling, and thus stratum corneum breakdown, include dermatitis (eczema), psoriasis, and the ichthyoses. Both eczema and psoriasis result from underlying epidermal changes that cause pathology at the level of the stratum corneum. On the other hand, the ichthyoses result from underlying defects in keratinization. Dermatitis, or eczema, is a skin reaction secondary to an underlying process, such as an immune response or infection. Dermatitis is characterized by a disruption in corneocyte formation in the setting of underlying epidermal keratinocyte spongiosis. Consequently, there is keratinocyte hyperproliferation and disturbed keratinization, which both cause scaling. In psoriasis, activated lymphocytes release cytokines that trigger epidermal hyperproliferation and leukocyte infiltration that similarly causes keratinocyte hyperproliferation and disturbed keratinization, resulting in scaling. Inherited ichthyoses, such as recessive X-linked ichthyosis, result from genetic defects that phenotypically present as skin scaling and diffuse xerosis. Recessive X-linked ichthyosis results specifically from steroid sulfatase deficiency that can affect the stratum corneum and clinically manifest with very dry skin and dark-colored scaling.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ruchusatsawat K, Wongpiyabovorn J, Protjaroen P, Chaipipat M, Shuangshoti S, Thorner PS, Mutirangura A. Parakeratosis in skin is associated with loss of inhibitor of differentiation 4 via promoter methylation. Human pathology. 2011 Dec:42(12):1878-87. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.02.005. Epub 2011 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 21663940]

Freeman SC, Sonthalia S. Histology, Keratohyalin Granules. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725734]

Seah BC, Teo BM. Recent advances in ultrasound-based transdermal drug delivery. International journal of nanomedicine. 2018:13():7749-7763. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S174759. Epub 2018 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 30538456]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUche LE, Gooris GS, Beddoes CM, Bouwstra JA. New insight into phase behavior and permeability of skin lipid models based on sphingosine and phytosphingosine ceramides. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Biomembranes. 2019 Jul 1:1861(7):1317-1328. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2019.04.005. Epub 2019 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 30991016]

Kim JH, Ahn B, Choi SG, In S, Goh AR, Park SG, Lee CK, Kang NG. Amino acids disrupt calcium-dependent adhesion of stratum corneum. PloS one. 2019:14(4):e0215244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215244. Epub 2019 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 30990830]

Arriagada F, Morales J. Limitations and Opportunities in Topical Drug Delivery: Interaction Between Silica Nanoparticles and Skin Barrier. Current pharmaceutical design. 2019:25(4):455-466. doi: 10.2174/1381612825666190404121507. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30947656]

Egawa G. Pathomechanism of 'skin-originated' allergic diseases. Immunological medicine. 2018 Dec:41(4):170-176. doi: 10.1080/25785826.2018.1540257. Epub 2019 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 30632910]

Goleva E, Berdyshev E, Leung DY. Epithelial barrier repair and prevention of allergy. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2019 Apr 1:129(4):1463-1474. doi: 10.1172/JCI124608. Epub 2019 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 30776025]

Bosko CA. Skin Barrier Insights: From Bricks and Mortar to Molecules and Microbes. Journal of drugs in dermatology : JDD. 2019 Jan 1:18(1s):s63-67 [PubMed PMID: 30681811]

Maarouf M, Maarouf CL, Yosipovitch G, Shi VY. The impact of stress on epidermal barrier function: an evidence-based review. The British journal of dermatology. 2019 Dec:181(6):1129-1137. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17605. Epub 2019 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 30614527]

Dawber RP, Marks R, Swift JA. Scanning electron microscopy of the stratum corneum. The British journal of dermatology. 1972 Mar:86(3):272-81 [PubMed PMID: 4259712]