Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Hamstring Muscle

Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Hamstring Muscle

Introduction

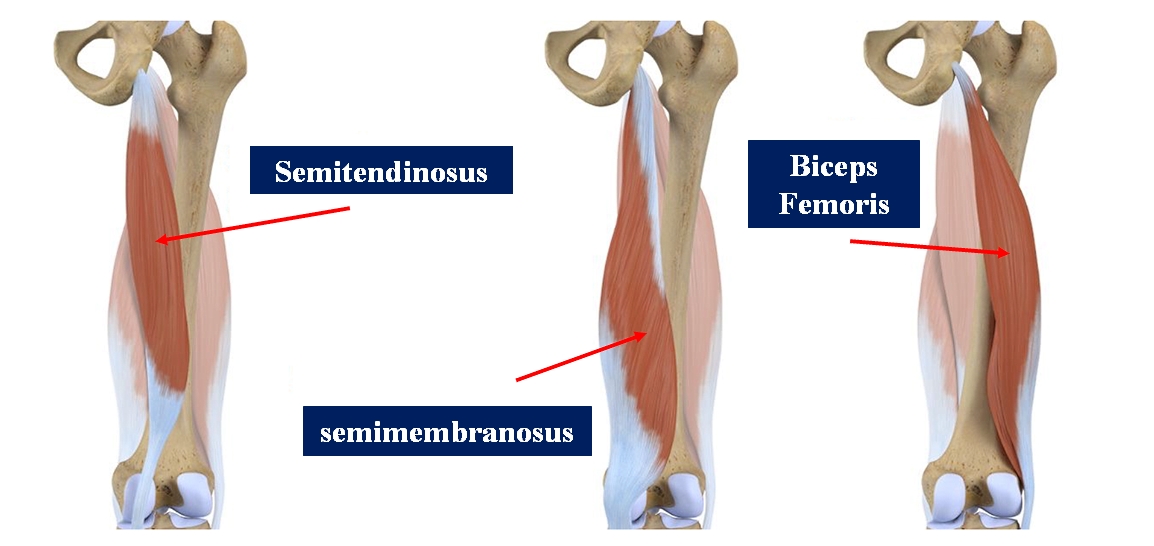

The hamstring muscle complex occupies the posterior compartment of the thigh and is comprised of three individual muscles (see Image. Hamstring Muscles). Together, they play a critical role in human activities ranging from standing to explosive actions such as sprinting and jumping. Hamstring injuries are common in elite and amateur sportspeople, and the treatment of such injuries ranges from conservative management to operative fixation. Uninjured hamstring tendons can be used as autografts in knee ligament reconstruction surgery.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and biceps femoris muscles comprise the hamstring muscle group.[1]

Biceps Femoris: Short Head

- Origin: Lateral lip of the linea aspera

- Insertion: The fibular head and lateral condyle of the tibia

- Function: Knee flexion and lateral rotation of the tibia

- Innervation: Fibular (common peroneal) nerve

- Vascular supply: Perforating branches of the deep femoral artery

Biceps Femoris: Long Head

- Origin: Ischial tuberosity

- Insertion: The fibular head and lateral condyle of the tibia

- Function: Knee flexion, lateral rotation of the tibia, and hip extension

- Innervation: Tibial nerve

- Vascular supply: Perforating branches of the deep femoral artery

Semitendinosus

- Origin: Lower, medial surface of the ischial tuberosity

- Insertion: Medial tibia (pes anserinus)

- Function: Knee flexion, hip extension, and medial rotation of the tibia (with knee flexion)

- Innervation: Tibial nerve

- Vascular supply: Perforating branches of the deep femoral artery

Semimembranosus

- Origin: Ischial tuberosity

- Insertion: Medial tibial condyle

- Function: Knee flexion, hip extension, and medial rotation of the tibia (with knee flexion)

- Innervation: Tibial nerve

- Vascular supply: Perforating branches of the deep femoral artery

Beginning at the pelvis and running posteriorly along the length of the femur, the majority of muscles within the hamstring complex cross both the femoroacetabular and tibiofemoral joints. The short head of the biceps femoris is an exception to this rule as it originates from the lateral lip of the femoral linea aspera, distal to the femoroacetabular joint. For this reason, some argue that the short head of the biceps femoris is not a true hamstring muscle.

Unlike the short head of the biceps femoris, all other hamstring muscles originate from the ischial tuberosity. The proximal, long head of the biceps femoris and semitendinosus muscles are linked by an aponeurosis that extends approximately 7 cm from the ischial tuberosity. The distal hamstrings form the superolateral (biceps femoris) and superomedial (semimembranosus and semitendinosus) borders of the popliteal fossa. The gastrocnemius primarily forms the inferior border of the popliteal fossa.[2]

The hamstring muscle group plays a prominent role in hip extension (posterior movement of the femur) and knee flexion (posterior movement of the tibia and fibula). Concerning the gait cycle, the hamstrings activate at the final 25% of the swing phase generating extension force at the hip and resisting knee extension. The hamstring muscles also play an essential role as a dynamic stabilizer of the knee joint. Operating in tandem with the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), the hamstrings resist anterior translation of the tibia during the heel strike phase of the gait cycle.[3]

The longest muscle in the hamstring group is the semitendinosus, measuring an average of 44.3 cm, followed by the long head of the biceps, which measures an average of 42.0 cm. The other two muscles in the group, the semimembranosus and the short head of the biceps, measure an average of 38.7 cm and 29.7 cm, respectively.[4] See Image. Muscles of the Hip and Thigh.

Embryology

A significant portion of lower extremity development occurs during weeks 4 to 8 of embryogenesis. Like all other skeletal muscle tissue, the hamstring muscles form from the embryonic mesoderm. The initial limb bud originates from the lateral plate mesoderm.[5] Migrating from the somites during the early embryonic phase, mesodermal cells differentiate into myoblasts, which duplicate and coalesce, eventually forming functional muscle tissue.[6] This occurs due to a complex array of physiological signals governing the subsequent organization and symmetry of the structures formed, for example, fibroblast growth factors, sonic hedgehog, and Wnt7a.[7]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

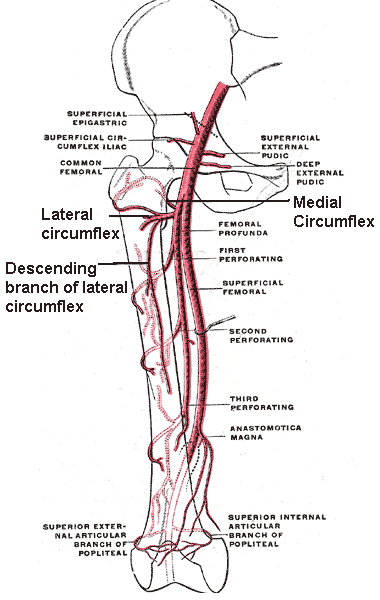

The hamstring muscle complex receives vascular supply from the perforating branches of the deep femoral artery, also known as the profunda femoris artery. The profunda femoris artery is a branch of the femoral artery.[8][9] The demarcation between the external iliac artery and the femoral artery is the inguinal ligament. See Figure. Branches of the Femoral Artery.

In general, the deep veins of the thigh share the same name as the major arteries they follow. The femoral vein is responsible for significant venous drainage of the thigh. It accompanies the femoral artery and receives additional venous drainage from the profunda femoris vein. Like the femoral artery, the femoral vein transitions to the external iliac vein at the level of the inguinal ligament.

The lymphatic drainage of the thigh also mirrors the arterial supply and eventually drains into the lumbar lymphatic trunks and cisterna chyli.

Nerves

The hamstring muscle complex is innervated by nerves that arise from the lumbar and sacral plexuses. These plexuses give rise to the sciatic nerve (L4-S3), which bifurcates into the tibial and common peroneal (fibular) nerves at the level of the tibiofemoral joint.[10] The tibial nerve innervates the semimembranosus, semitendinosus, and long head of the biceps femoris muscles. The common peroneal branch of the sciatic nerve innervates the short head of the biceps femoris.

Physiologic Variants

Although uncommon, surgeons must remain aware of hamstring muscle anatomical variations. The hamstring muscle group, except for the short head of the biceps femoris, typically originates from a conjoint muscle tendon arising from the ischial tuberosity. Interestingly, there are reports which reveal variants where the semitendinosus and the long head of the biceps femoris appear from distinct tendinous origins.[3] Another report published in 2013 revealed findings of a third head of the biceps femoris and an anomalous muscle inserted into the semimembranosus.[11]

There is also a report of a patient with a bilateral absence of the semimembranosus muscles. This finding was noticed incidentally on MRI after the patient presented with knee pain after a fall.[12] Although the article did not indicate whether or not the patient had experienced symptoms related to this atypical finding prior to his presentation, this finding may be relevant in the context of ACL reconstruction, as hamstring autografts are a common choice.

Common peroneal nerve entrapment neuropathy most commonly occurs at the level of the fibular head and neck. A 2018 report revealed the findings of common peroneal neuropathy associated with variation of the short head of the biceps femoris. In this case, the location of the common peroneal nerve was within a 4.4 cm tunnel between the gastrocnemius and the short head of the biceps femoris.[13]

Surgical Considerations

The vast majority of hamstring injuries are manageable nonoperatively. However, hamstring tendon avulsion often requires surgical intervention. Hamstring tendon avulsions are treated endoscopically with fixation of the torn segment of the hamstring tendon to the ischial tuberosity.[14] Surgical repair of chronic proximal hamstring rupture can have augmentation with an Achilles tendon autograft.[15]

Ischial apophyseal avulsion fractures are extremely rare. Studies report that they account for only 1.4 to 4% of all hamstring injuries.[16] Avulsion fractures with less than 1 cm of displacement are candidates for conservative management. Patients are advised to limit hamstring stretching, preventing the fractured segment of the ischial apophysis from becoming further displaced.[17] Surgical fixation is necessary for patients with ischial apophyseal avulsion fractures displaced more than 1 cm or those experiencing symptomatic malunion. Early intervention is advised to decrease the risk of ischiofemoral impingement.[18]

The hamstring muscle is harvestable as an autograft in ACL reconstruction. The quadruple hamstring autograft involves the semitendinosus and gracilis muscles and is known to be one of the strongest grafts available.[19] Compared to patellar tendon grafts, hamstring autografts offer a decreased risk of donor site trauma, patellofemoral crepitation, kneeling pain, and loss of more than 5 degrees of knee extension.[20] In contrast, studies demonstrate that hamstring autografts have an increased risk of laxity and functional hamstring weakness.[20] No conclusive evidence exists to date suggesting that one graft material produces superior long-term results. Kocher et al. found no association between graft type and patient satisfaction in patients undergoing ACL reconstruction using hamstring and patellar grafts.[21]

Clinical Significance

Hamstring strains are common in both elite and recreational athletes. In addition to being highly prevalent, hamstring injuries are often slow to heal and tend to recur. Nearly one-third of those who suffer from a hamstring injury are estimated to reinjure themselves within one year of returning to their sport.[22] Most hamstring strains occur in high-risk activities such as sprinting, where rapid changes in speed or direction cause excessive muscle lengthening. The biceps femoris is the most frequently injured of the hamstrings, followed by the semimembranosus and the semitendinosus.[23][24]

Typically, hamstring injuries are characterized by pain in the posterior thigh, which can be exacerbated by knee flexion and hip extension. In severe injuries, patients may also report hearing a popping sound. When evaluating a patient with a possible hamstring injury, it is important that clinicians also consider other diagnostic possibilities, such as lumbosacral radiculopathy, adductor strain, or a femoral stress fracture.

Hamstring strain injuries classify as mild (Grade I), moderate (Grade II), or severe (Grade III) based on the severity of patient symptoms.[25] Grade I injuries are characterized by minimal pain and functional impairment, with minimal disruption to the hamstring myofibrils present. Grade II injuries are partial thickness tears to the musculotendinous fibers. Patients exhibit increased pain with definite strength loss. Grade III tears present with severe pain, hematoma, significant strength loss, and a full-thickness tear to the hamstring muscle or tendon. Orthopedic consultation is the recommendation for Grade III and Grade II/III tears, which affect the distal aspect of the hamstring.

In the acute phase, hamstring injuries are initially managed with protection, rest, ice, compression, and elevation to limit inflammation and swelling.[26] Patient pain tolerance should dictate the range of motion, as excessive hamstring stretching may lead to scar tissue formation.[27] The role of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in hamstring injury is somewhat controversial, with some studies failing to show recovery benefits and others demonstrating possible adverse effects.[28][29] However, short (5 to 7 days) courses of NSAIDs do not significantly hamper recovery and should be used primarily as analgesics. Alternative pharmacologic agents, such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP), have been explored to enhance athlete recovery. There is no strong evidence to support the use of PRP for muscle strain injury.[30]

In patients who have healed to the point where they can begin therapeutic activities, exercise regimens that focus on eccentric contraction have been shown to shorten recovery time significantly.[31] These regimens can be altered based on the patient’s rehabilitation phase and can continue to decrease the re-injury rate.[32] Although hamstring stretching is commonly advocated to decrease the probability of re-injury, hamstring flexibility training has not demonstrated a decrease in the incidence of hamstring re-injury.

Studies have also emphasized the importance of neuromuscular control of the lumbopelvic region. A 2004 prospective randomized study found that patients suffering from acute hamstring strain injury who were rehabilitated using a progressive agility and trunk stabilization program showed lower re-injury rates than those enrolled in a more standard progressive stretching and strengthening program.[33]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Muscles of the Hip and Thigh. The gluteal muscles include the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus. Hip muscles include the piriformis, gemellus superior, gemellus inferior, and obturator internus. Thigh muscles include the adductor magnus, vastus lateralis, biceps femoris, semitendinosus, hamstring tendons, and gracilis.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Branches of the Femoral Artery. This illustration shows the following structures: common femoral artery, deep femoral artery (femoral profunda), superficial femoral artery, perforating arteries, lateral circumflex artery, medial circumflex artery, descending branch of the lateral circumflex artery, anastomotica magna, and superior external and internal articular branches of the popliteal artery.

Mikael Häggström, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Woodley SJ, Mercer SR. Hamstring muscles: architecture and innervation. Cells, tissues, organs. 2005:179(3):125-41 [PubMed PMID: 15947463]

Greenwood K, Zyl RV, Keough N, Hohmann E. Defining the popliteal fossa by bony landmarks and mapping of the courses of the neurovascular structures for application in popliteal fossa surgery. Anatomy & cell biology. 2021 Mar 31:54(1):10-17. doi: 10.5115/acb.20.179. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33594009]

Koulouris G, Connell D. Hamstring muscle complex: an imaging review. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2005 May-Jun:25(3):571-86 [PubMed PMID: 15888610]

van der Made AD, Wieldraaijer T, Kerkhoffs GM, Kleipool RP, Engebretsen L, van Dijk CN, Golanó P. The hamstring muscle complex. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA. 2015 Jul:23(7):2115-22. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2744-0. Epub 2013 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 24190369]

Buckingham M, Bajard L, Chang T, Daubas P, Hadchouel J, Meilhac S, Montarras D, Rocancourt D, Relaix F. The formation of skeletal muscle: from somite to limb. Journal of anatomy. 2003 Jan:202(1):59-68 [PubMed PMID: 12587921]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTickle C. How the embryo makes a limb: determination, polarity and identity. Journal of anatomy. 2015 Oct:227(4):418-30. doi: 10.1111/joa.12361. Epub 2015 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 26249743]

Tickle C, Barker H. The Sonic hedgehog gradient in the developing limb. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Developmental biology. 2013 Mar-Apr:2(2):275-90. doi: 10.1002/wdev.70. Epub 2012 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 24009037]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTomaszewski KA, Henry BM, Vikse J, Pękala P, Roy J, Svensen M, Guay D, Hsieh WC, Loukas M, Walocha JA. Variations in the origin of the deep femoral artery: A meta-analysis. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2017 Jan:30(1):106-113. doi: 10.1002/ca.22691. Epub 2016 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 26780216]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChoy KW, Kogilavani S, Norshalizah M, Rani S, Aspalilah A, Hamzi H, Farihah HS, Das S. Topographical anatomy of the profunda femoris artery and the femoral nerve: normal and abnormal relationships. La Clinica terapeutica. 2013:164(1):17-9. doi: 10.7417/T.2013.1504. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23455736]

Tomaszewski KA, Graves MJ, Henry BM, Popieluszko P, Roy J, Pękala PA, Hsieh WC, Vikse J, Walocha JA. Surgical anatomy of the sciatic nerve: A meta-analysis. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 2016 Oct:34(10):1820-1827. doi: 10.1002/jor.23186. Epub 2016 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 26856540]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChakravarthi K. Unusual unilateral multiple muscular variations of back of thigh. Annals of medical and health sciences research. 2013 Nov:3(Suppl 1):S1-2. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.121206. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24349835]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSussmann AR. Congenital bilateral absence of the semimembranosus muscles. Skeletal radiology. 2019 Oct:48(10):1651-1655. doi: 10.1007/s00256-019-03210-3. Epub 2019 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 30982941]

Park JH, Park KR, Yang J, Park GH, Cho J. Unusual variant of distal biceps femoris muscle associated with common peroneal entrapment neuropathy: A cadaveric case report. Medicine. 2018 Sep:97(38):e12274. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012274. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30235672]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLempainen L, Banke IJ, Johansson K, Brucker PU, Sarimo J, Orava S, Imhoff AB. Clinical principles in the management of hamstring injuries. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA. 2015 Aug:23(8):2449-2456. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-2912-x. Epub 2014 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 24556933]

Folsom GJ, Larson CM. Surgical treatment of acute versus chronic complete proximal hamstring ruptures: results of a new allograft technique for chronic reconstructions. The American journal of sports medicine. 2008 Jan:36(1):104-9 [PubMed PMID: 18055919]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLiu H, Zhang Y, Rang M, Li Q, Jiang Z, Xia J, Zhang M, Gu X, Zhao C. Avulsion Fractures of the Ischial Tuberosity: Progress of Injury, Mechanism, Clinical Manifestations, Imaging Examination, Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis and Treatment. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2018 Dec 27:24():9406-9412. doi: 10.12659/MSM.913799. Epub 2018 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 30589058]

Sherry M. Examination and treatment of hamstring related injuries. Sports health. 2012 Mar:4(2):107-14 [PubMed PMID: 23016076]

Gidwani S, Jagiello J, Bircher M. Avulsion fracture of the ischial tuberosity in adolescents--an easily missed diagnosis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2004 Jul 10:329(7457):99-100 [PubMed PMID: 15242916]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFrank RM, Hamamoto JT, Bernardoni E, Cvetanovich G, Bach BR Jr, Verma NN, Bush-Joseph CA. ACL Reconstruction Basics: Quadruple (4-Strand) Hamstring Autograft Harvest. Arthroscopy techniques. 2017 Aug:6(4):e1309-e1313. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2017.05.024. Epub 2017 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 29354434]

Goldblatt JP, Fitzsimmons SE, Balk E, Richmond JC. Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: meta-analysis of patellar tendon versus hamstring tendon autograft. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 2005 Jul:21(7):791-803 [PubMed PMID: 16012491]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKocher MS, Steadman JR, Briggs K, Zurakowski D, Sterett WI, Hawkins RJ. Determinants of patient satisfaction with outcome after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2002 Sep:84(9):1560-72 [PubMed PMID: 12208912]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHeiderscheit BC, Sherry MA, Silder A, Chumanov ES, Thelen DG. Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 2010 Feb:40(2):67-81. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2010.3047. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20118524]

Askling CM, Tengvar M, Saartok T, Thorstensson A. Acute first-time hamstring strains during high-speed running: a longitudinal study including clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings. The American journal of sports medicine. 2007 Feb:35(2):197-206 [PubMed PMID: 17170160]

Opar DA, Williams MD, Shield AJ. Hamstring strain injuries: factors that lead to injury and re-injury. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). 2012 Mar 1:42(3):209-26. doi: 10.2165/11594800-000000000-00000. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22239734]

Hamilton B, Valle X, Rodas G, Til L, Grive RP, Rincon JA, Tol JL. Classification and grading of muscle injuries: a narrative review. British journal of sports medicine. 2015 Mar:49(5):306. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093551. Epub 2014 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 25394420]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrukner P. Hamstring injuries: prevention and treatment-an update. British journal of sports medicine. 2015 Oct:49(19):1241-4. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094427. Epub 2015 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 26105015]

Järvinen MJ, Lehto MU. The effects of early mobilisation and immobilisation on the healing process following muscle injuries. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). 1993 Feb:15(2):78-89 [PubMed PMID: 8446826]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceReynolds JF, Noakes TD, Schwellnus MP, Windt A, Bowerbank P. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs fail to enhance healing of acute hamstring injuries treated with physiotherapy. South African medical journal = Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde. 1995 Jun:85(6):517-22 [PubMed PMID: 7652633]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMishra DK, Fridén J, Schmitz MC, Lieber RL. Anti-inflammatory medication after muscle injury. A treatment resulting in short-term improvement but subsequent loss of muscle function. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1995 Oct:77(10):1510-9 [PubMed PMID: 7593059]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEngebretsen L, Steffen K, Alsousou J, Anitua E, Bachl N, Devilee R, Everts P, Hamilton B, Huard J, Jenoure P, Kelberine F, Kon E, Maffulli N, Matheson G, Mei-Dan O, Menetrey J, Philippon M, Randelli P, Schamasch P, Schwellnus M, Vernec A, Verrall G. IOC consensus paper on the use of platelet-rich plasma in sports medicine. British journal of sports medicine. 2010 Dec:44(15):1072-81. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.079822. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21106774]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKraiem Z, Alkobi R, Sadeh O. Sensitization and desensitization of human thyroid cells in culture: effects of thyrotrophin and thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin. The Journal of endocrinology. 1988 Nov:119(2):341-9 [PubMed PMID: 2462004]

Brooks JH, Fuller CW, Kemp SP, Reddin DB. Incidence, risk, and prevention of hamstring muscle injuries in professional rugby union. The American journal of sports medicine. 2006 Aug:34(8):1297-306 [PubMed PMID: 16493170]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSherry MA, Best TM. A comparison of 2 rehabilitation programs in the treatment of acute hamstring strains. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 2004 Mar:34(3):116-25 [PubMed PMID: 15089024]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence